In 2020 Joseph H. Larnerd, an assistant professor at Drexel University, assigned his students—homebound due to the Covid-19 pandemic—a curious task: they were to make a museum of their mundanities. Through careful research and thoughtful descriptions— written in the form of exhibition display texts—the students would elevate an object around them to the level of art or artifact. The Museum of Where We Are project has brought the resulting objects and descriptions together in an exhibition, on view at the Rincliffe Gallery at Drexel through March 2022.

At a time when so many of us felt like the world was crunching inwards on us, Larnerd challenged the minds under his tutelage to re-examine what is special and what is structural to our material culture and society, and to appreciate how, so often, all it takes to make an object important is to recognize it as such.

The task Larnerd set for his students must, we imagine, resonate deeply with anyone who has ever felt a connection to an object that others might squint at and ask, “what’s the big deal?” This happens all the time, frankly, to those of us in the world of antiques.

In our own home, there is a long low shelf covered with treasures. When we find something small and special—a palm-sized sculpture, a trinket box, a piece of sea glass, a rock—we often look to each other, wordlessly confirming that, yes, this should go on the shelf. There it will join a tile hand-painted with a cross-section of a cherry pit, a twentieth-century clay bust, a deer vertebra wrapped in wire, three wooden croquet balls, a silver creamer and sugar bowl, a mug from a farm stand Pippa’s family once ran, and a row of glass jars, each with a label denoting a place and a year.

Our treasure shelf is, for both of us, a continuation of a habit of collection and display that began when we were young. Like many people in antiques, the impulse to collect was followed by an urge to understand, and not the other way around. For Ben it began with rocks—“pretty rocks” to be more specific. For Pippa it was miniatures, toy boats, and glass: a small glass bottle full of tiny garnets; a larger glass bottle containing a ship; a glass bottle that held nothing but caught the light just so.

As we reflected on how to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of The Magazine ANTIQUES, we found ourselves pondering how all of us—contributors, editors, advertisers, and readers—got started. How is it that, one hundred years on, a wholly new readership satiates its curiosity the same way and from the same impulses as the magazine’s original readers?

Footed sugar bowl and cover, probably Boston and Sandwich Glass Company. Vaseline lead glass; height 5 3/8 inches (including cover). Toledo Museum of Art, gift of Mrs. Harold G. Duckworth.

We looked to our shelf for a lens through which to examine why we collect—or, more accurately, accumulate— the past, embracing it and bringing it close. Though neither of us collects glass today, our minds kept landing on those jars and the sea glass inside, thinking about the objects those tide-worn shards came from, and the curiosity such things inspired when we were young.

Diane Wright, senior curator of glass and contemporary craft at the Toledo Museum of Art, thinks glass is a starting point for many collectors because of its ubiquity and accessibility. “There is a great familiarity with glass,” she says. It’s in our windows, on our tables, in our cars, and our places of work. We eat on it, drink from it, read time through it on our wristwatches, and scroll Instagram through it on our phones. But as commonplace as glass is, it has a fascination: as a thing that is so delicate and so fragile, and yet, if cared for properly, will last forever. Glass is a little like love that way.

The Toledo Museum of Art has one of the preeminent glass collections in the world, holding pieces dating back to ancient times. The collection’s American-made glass is, of course, of comparatively much more recent vintage—and more recent than you’d think. Glass manufacturing came late to British North America. England prohibited such enterprises in its colonies, lest they compete with glassmakers in the mother country.

Demand for glass was high enough, however, that there were attempts to operate a glasswork in the American colonies despite the ban, beginning in Jamestown in 1608. All of them failed.

According to an article by Helen McKearin in the August 1941 issue of this magazine, American glass did not find its footing until the glasshouse of Casper Wistar opened eight miles from Salem, New Jersey, in 1739. Wistar had brought Belgian and Dutch glassworkers over in defiance of the British ban and, in doing so, “became responsible for an American glass tradition.”

Around 1820, blown three-mold glass manufacturing made the production of tableware cheaper and faster. While it didn’t look as good as real, wheel-cut glass from Ireland and England, the molded pieces were acceptable, less-expensive versions of their faceted cousins. Lacy or pressed glass, too, offered a semi-mechanized version of a European product at a more modest price point.

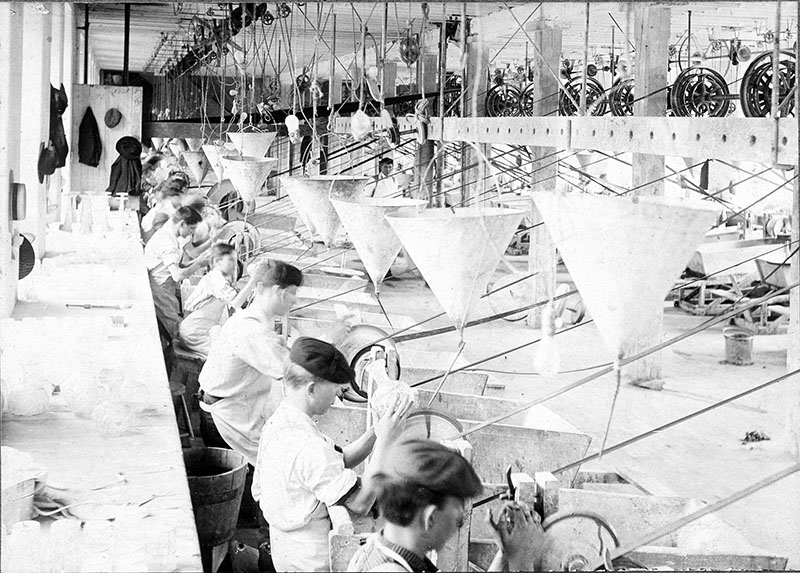

Originally, early American glassmakers apprenticed young boys, teaching them the trade while benefitting from their quick feet, high energy, and inexpensive labor. But as glass manufacturing expanded and industrialized, the apprenticeship model disappeared. By the early nineteenth century, American glassworks teemed with young boys who, instead of learning a craft from the men they worked under, were assigned small and unskilled (but important) repetitive tasks. A child as young as ten might work night shifts as a turning-out boy, a mold-boy, a carrying-in boy, or a “lehr” boy, who helped at the annealing kiln. It was dangerous, poorly paid work. The temperature on the factory floor regularly exceeded 100 degrees F, and heavy clouds of dust led to eye, skin, and lung complications.

Further technical developments around the turn of the twentieth century made possible the mechanical production of the genuine article: cut glass, produced at scale. Americans were avid consumers, and even with profound innovations the glass industry struggled to keep up with demand. Their answer to the growing pains was often to throw people, specifically young people, at the problem.

By the 1920s—as documented by photographer and activist Lewis Hines in his early twentieth-century images from glassworks—in one hundred years, that is, bad industrial labor practices had changed little. The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics reported in 1927 that 5,658 children under sixteen worked in the glass industry, down from 7,116 in 1899. Given the informality of much of the employment, we can assume the official numbers are only a low approximation of the actual totals.

After mulling over one photo of a young boy at a glasscutting wheel, Larnerd told us in an email: “If the boy’s vessel broke, the glass might be salvaged, melted down, and reused; the same could not be said for his face and little limbs. Such images encourage material culturists to think about the various worker-level ‘growing pains,’ to use your evocative phrase, of industrialization.”

In 1904 the National Child Labor Committee was formed to advocate for and pursue federal regulation of child employment. Also that year, the Libbey Glass Company, led by Edward Drummond (who also founded the Toledo Museum of Art), exhibited a bravura piece of glass dubbed the Libbey Punch Bowl at the Saint Louis World’s Fair. It was “cut within an inch of its life,” curator Diane Wright says of the punch bowl, with its countless facets and a two-foot diameter rim. It showed World’s Fair visitors what was possible when Yankee expertise, industry, and capital were brought to bear. No longer was America trying to catch up.

The Libbey Punch Bowl, still in the collection the Toledo Museum of Art, weighs in at 134 pounds, holds fifteen gallons of liquid, and was carefully faceted by two of the company’s top glasscutters, J. Rufus Denman and Patrick W. Walker. There is no evidence children were involved in its manufacture, but the fact it was made—that it indeed could be made—relied on an industrial history (and, at that time, a present) far less perfect than the punch bowl’s facets.

Antiques, almost as a rule, have complicated pasts. Much of the heirloom silver on our tables was mined by the enslaved; fine portraits were paid for with the wealth of exploiters; beautiful gilding was manufactured in deadly conditions. Exquisitely crafted objects made today will themselves be antiques one day. In much the same way, collectors and others will then, as now, reflect on their making and wonder if these things were worth it, and what “worth it” even means. By examining these objects together, we gain a better understanding of each, and of ourselves. To quote Larnerd: “What might the rhymes and dissonances between the objects suggest about their origins and purposes? Sometimes to see an artifact, you need to look away from it.”

Explaining why—to, let’s say, an aunt at the dinner table—a massive cut-glass punch bowl is remarkable can become, we’ve found, an excruciating exercise in unreciprocated enthusiasm. And yet, just as a well-placed ray of light can create a kaleidoscopic show through a prism, we know that reexamination of a form can trigger greater appreciation for, and understanding of, what went into each of its facets. That’s why places like The Magazine ANTIQUES are so important. The magazine gives us a place to reflect, to explore, and to acknowledge as structural those things that we know to be so. It’s a museum of where we’ve been, of what we value, and of where we are.