The circuit ran from Troy, New York, to Bennington, Vermont, and from Keene, New Hampshire, to Worcester, Massachusetts. Some men traveled the route regularly, making their way from one place to another in search of work. Others performed journeyman labor in order to pay for their expenses on the road as they searched for open land to make their own. Most, though, simply traveled as they were needed, tramping from kiln to kiln as opportunity had it.

By the time John Hilfinger was following this circuit in the middle of the nineteenth century, something was changing in the pottery business. Perhaps it was due to the influx of men like Hilfinger himself— who had recently crossed the Atlantic from his native Württemberg, Germany—bringing their extensive experience, experience that can readily be seen in the quality of their decorated vessels. Perhaps it was just the passage of time. Whatever the cause, wares that had subtly patterned general-store shelves and the larders of practical homesteaders for decades were transforming. The pots with striking lines of cobalt blue on simple gray stoneware were becoming art.

The Norton pottery was one stop on the circuit, and its roots in Bennington ran deep. Norton pottery, Jamie Franklin, curator of the Bennington Museum, tells us, predates the state of Vermont itself by six years.

In 1785 Captain John Norton traveled to Bennington with his small family from Williamstown, Massachusetts. Vermont was still petitioning for statehood at the time, and, as a result, was effectively an independent republic. It operated, the first director-curator of the Bennington Museum, John Spargo, wrote in his 1926 book, The Potters and Potteries of Bennington, “with its own coinage, post-offices and post-roads; its own naturalization laws and its own independent foreign relations.” Yet, despite this separation, the not-yet-state was deeply intertwined with neighboring states through commerce and shared military service. It was to this interconnectivity that Captain Norton hitched his hopes.

When Norton first arrived in Bennington, he purchased a property blessed with two assets: a high volume of passing traffic and good clay. His tract was traversed by the main highway between Canada and Massachusetts Bay, was on the road from Bennington to Pownal, Vermont, and had significant deposits of the red clay used in making “red ware” pottery—the earthy browns and reds of which can be seen in milk pans, small jugs, and crocks throughout the eastern United States.

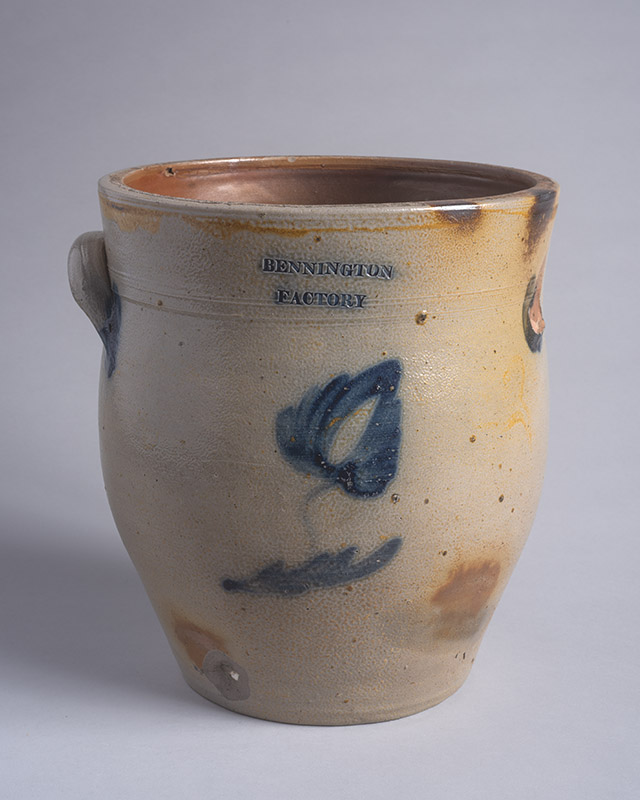

It isn’t known what background, if any, Norton had in pottery before landing in Bennington, but once there, clay became his livelihood. For the family’s first ten years, the red clay underneath his feet was formed in his workshop, fired in his kiln, and sold to his neighbors. Only around 1800 did the Nortons begin to make the pieces of stoneware that would make them famous. The first surviving records showing the importation of clay for stoneware from Troy, New York, are dated 1810, and the early pieces formed from this clay were simple. Decoration was minimal: the outline of leaves or a number to indicate the size of the clay container, rendered in cobalt. Occasionally, a piece has incised decoration.

However, artists love to fill a canvas, and the simplicity of these early pieces would not last.

Today, there are few elements of stoneware as iconic as those touched with the cobalt flourishes painted by Norton’s men in Bennington. They seem infused with a reckless whimsy—an effect that may well come from their largely unscripted nature. As Jamie Franklin remarked, the pottery was sold by its form and size—not for its decorations. The price lists that survive make clear that, other than specific commissioned jobs, the decorations were considered a form of branding, not art. If they caught the eye of a passerby and led to a sale, their purpose was served.

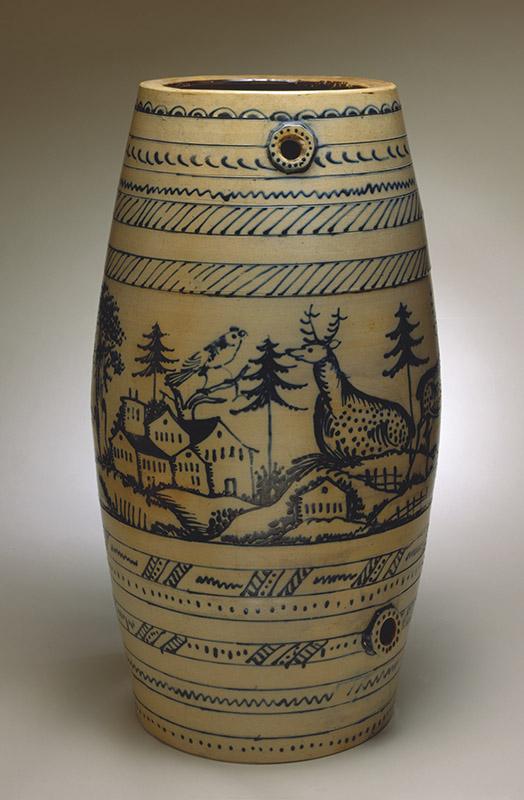

The artists often used what Franklin calls “factory design” decorations—a cobalt leaf, a flower, an occasional resting deer—and so surviving examples of these are relatively common. But they were also welcomed to explore and indulge their imaginations. The artists would, at times, engage in a bit of narration, constructing scenes from two or more common elements—a crock from this period showing two hens pecking at the ground serves as a prime example.

The art on the vessels progressed parallel to the company’s own transformation. Captain Norton and his sons worked together in the business, and, as many fathers dream, in 1812 the firm became “Capt. Norton and Sons.” But it wasn’t until the third generation that the most iconic pieces were produced. Under the guidance of Norton’s grandson Julius, later joined by his cousin Edward, the company produced wares of truly superb quality and with decorations of exceptional scope and skill.

It was during this time that John Hilfinger made his mark, if not his name. While he is among the best known of the stoneware decorators today, and many of the finest cobalt floral and bird decorations have been attributed to him, he was, at the time, largely unknown. His name first appears in the public record in his wedding announcement in the West Troy Advocate of June 15, 1853; he is recorded as working in Bennington between 1855 and his enlistment in 1864 in the Union army. In his army paperwork, Hilfinger was described as a “Painter” by occupation, while by 1866 the Worcester city directory lists him as a “stone ware painter.” After the war, Hilfinger returned to work at the Norton pottery, then followed the well-worn path of itinerant painters, moving between Worcester, Fort Edward, New York—another stoneware manufacturing hub—and West Troy.

Hilfinger’s hand always appears steady and bold. His figures are not bound by any sense of relative scale, but the contours are clear. They speak to a world of well-worked, little luxuries. In his book, Spargo tells us that art is “the little extra flourish which a man adds to his work.” This is an entirely fitting tribute to the work of Hilfinger and his contemporaries. The rich cobalt blue—made from a mixture of oxides of cobalt and manganese—can be so deep that at times it seems to plunge into a midnight blackness.

The Norton potters and painters were a continuously creative and innovative marriage of craftsmen and artists, merchants and laborers, high art and the everyday. The Norton family kept the enterprise going for more than a century.

Today, the market for Norton pieces with cobalt decoration reflects collectors’ interest in form over function. The more highly decorated pieces—the large painted water coolers that only rarely come onto the market, for example—can command hundreds of thousands of dollars at auction. A smaller, plain “Bennington” leaf crock sells for a couple hundred. Both are impressive prices for jars originally intended for pickles and butter, and so we would caution any would-be collector to refrain from using them to store kitchen utensils—no matter how tempting.