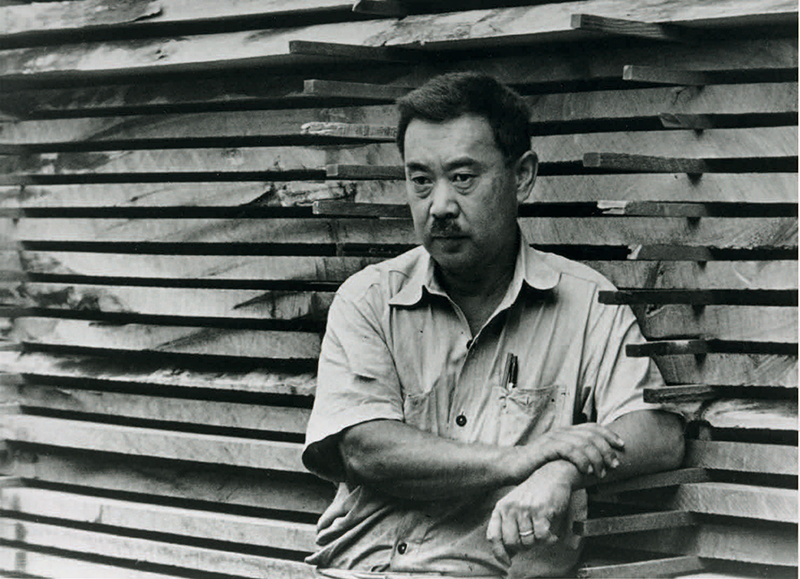

The revered American studio craftsman George Nakashima famously said that, in the furniture he designed and made, he sought to reveal “the soul of a tree.” He did so by celebrating wood with vivid grains that other designers might have regarded as distracting imperfections and, most significantly, by leaving alone the natural contours of the tree trunk from which a slab of wood was cut—creating tables, his best-known furniture form, with what he called a “free edge.”

Today, the term most frequently employed to describe such furniture is “live edge,” and, some thirty-two years after Nakashima’s death, his spirit is very much alive itself. Not only is the Nakashima Studio in New Hope, Pennsylvania thriving under the leadership of daughter Mira Nakashima, herself a deeply respected designer, but a new generation of craftspeople has embraced his philosophy and exacting approach to joinery. Even larger scale furniture making operations now create faux live edges using sophisticated cutting devices to simulate the natural profile of a tree. Make what you will of the latter development— is it egalitarian, or merely mercenary?—the wide appeal of live-edge furniture is a remarkable example of how even the most eccentric design idioms can become embraced and even beloved by the public at large. George Nakashima let a tree talk, and the world listened.

Nakashima’s story has been often told but bears repeating. Born in Spokane, Washington in 1905, the first-generation son of Japanese immigrants, he entered the University of Washington to study forestry, but switched his major to architecture, and spent one undergrad year at the École Americaine des Beaux-Arts in Fontainebleau, France. After earning his BA in 1929, he went on to take a master’s degree in architecture at MIT in 1931.

Soon after, he began to travel, working for a time in Paris—where he made almost daily visits to observe the construction of Le Corbusier’s Swiss Pavilion dormitory at the Cité Internationale Universitaire— before setting off again, sailing on a tramp steamer to Asia. In Tokyo he met the Czech-born American architect Antonin Raymond, entered his employment, and oversaw construction of a Raymond-designed ashram dormitory in India. Nakashima finally returned home to the US in early 1941. Within a few months, despite his cosmopolitanism, and his professional and academic credentials, he was ensnared in the xenophobic hysteria that followed the American entry into World War II and was sent to an internment camp for Japanese Americans in Idaho. But there, at age thirtyseven, he reinvented himself with help and guidance from fellow internee Gentaro Hikogawa, a master of traditional Japanese woodworking. Hikogawa gave Nakashima both a knowledge of materials and tools and a vehicle through which to express his creativity. Together, the men demonstrated that it is possible to conjure beauty even in the midst of abject want.

Thanks to Raymond’s intercession, Nakashima was released from the internment camp in 1943, and he and his family moved to Raymond’s farm near New Hope. Forbidden by wartime regulations to work as a designer professionally, Nakashima tended to the farm’s chicken flock by day and worked on furniture pieces by night. In 1946 he was at last able to open his own studio, and over the rest of the decade began to accrue private commissions and even designed a Windsor chair and coffee table—not a live-edge design—for Knoll. By the early 1950s, Nakashima had begun to win awards for his craftsmanship, and the rest is history. Today you will likely find his works in any modern design gallery or auction of note. And chances are that if you wander into a contemporary furniture showroom, you’ll see something influenced by—or ripping off—his designs.

Nakashima did fall off the design radar a bit in the 1960s and `70s, when sleeker designs in upholstered foam rubber and plastic and the “high-tech” look were the order of the day. But he regained prominence as part of the resurgence of interest in mid-century modernism in the 1990s—a handmade counterpoint to the mass-produced lines by Charles and Ray Eames and others. Robert Aibel, principal of Moderne Gallery in Philadelphia and perhaps the leading dealer in Nakashima’s work, admits that if was “dumb luck” that he got in early on the designer’s market, in 1985. “I thought it was important,” he recalls. “I wanted to handle it. I didn’t know people would care that much.”

But popular success breeds problems. “The influence, or in most cases imitation, of George’s work has been going on for a very long time,” says Aibel, who befriended the craftsman in his later years and uses his first name with a casualness we can’t help but envy. “There’s this image that these boards just jump on top of legs and become a free edge table.”

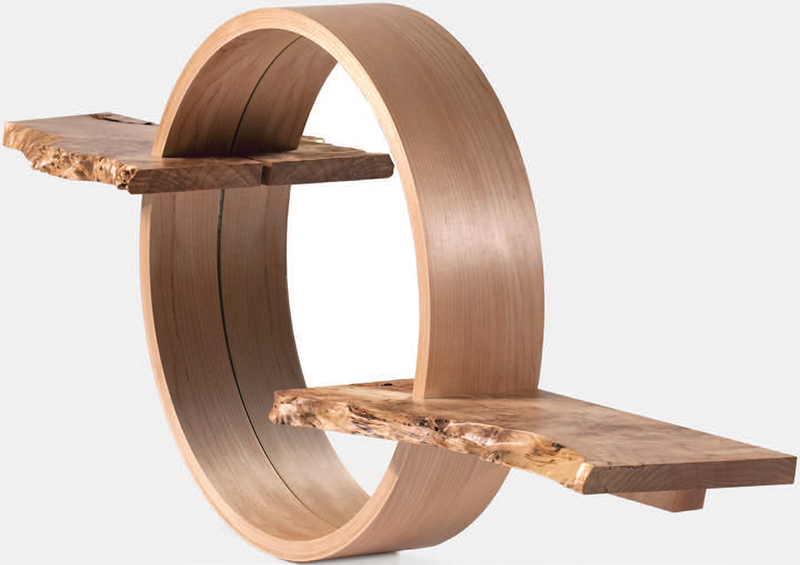

Indeed, contemporary craftspeople who are Nakashima disciples walk a fine line. Miriam Carpenter, who worked for a time under Mira Nakashima, creates pieces in the live-edge style and has become a respected designer in her own right. But others often find themselves forced to justify their work. Leigh and Cliff Spencer, founders of Alabama Sawyer, a Birmingham-based boutique furniture maker, know what it’s like to be compared to Nakashima and to have to defend the intention and intellect behind their designs. “On one hand,” Leigh says, “making a slab table is the easiest thing to do. You buy a slab, you sand it,” and so forth. But the job of a furniture maker, Cliff explains, “is to cut wood and control movement,” while communicating a particular perspective through those two actions. Finesse is essential to making great live-edge work. It’s a delicate, measured, and precise process, just like the Japanese joinery central to Nakashima’s practice. The Spencers—who say that they have used some of the same sources for wood as Nakashima once did—explain that their practice isn’t an attempt to duplicate. Different eyes produce different art.

Even worse, the current zeitgeist’s constant search for novelty has bred some near-nauseating bastardizations of the Nakashima style. One such trend is to fill in the imperfections of a live-edge slab with epoxy resin, often in vivid Jolly Rancher hues. Jennifer- Navva Milliken, executive director and chief curator of Philadelphia’s Center for Art in Wood, calls such crazes “Tumblr design”—a reference to the image-, video-, and microblog-sharing website. When designers scroll constantly through images in search of both inspiration and whatever seems to catch the popular eye, the result, she says, is an “oh-that-looks-cool-ism” that runs counter to the deliberate craftsmanship and the meditation on wood that Nakashima brought to the live-edge form.

And so, some live-edge work is art and some isn’t. Be warned, though, that price isn’t a strong signifier of which is which. Nakashima’s pieces are expensive. Last spring, a coffee table from his Minguren furniture line brought $72,300 at the Atlanta auction house Ahlers and Ogletree. Mira Nakashima achieved an auction record herself in 2018 when a table and chair set she designed sold for $150,000 at Freeman’s auction house in Philadelphia. But work that isn’t as storied is often similarly pricey. Slabs of wood are expensive, live-edge design is having a moment, and chic equals expensive. If you want a contemporary live-edge dining table, expect to pay $40,000 or more.

It is the thoughtfulness with which Nakashima approached his work that earned him such deep and enduring esteem. And in this lies the difference between Nakashima’s free edge and much of today’s live edge: the reflection and care behind it. For all its simplicity, the free edge was carefully, painstakingly crafted—as if the maker and the material worked in dialogue to shape the end creation. This, to us, seems the mark of the highest form of art and craft.

Research assistance for this article was provided by Lily Jenden.

BENJAMIN DAVIDSONandPIPPA BIDDLEare the founders of Quittner, a homewares and lighting studio in Germantown, New York