Lightning splits a swollen sky. Small and powerless, the human figures below are all but engulfed in the swirling shadows of the tempest. The composition threatens to subsume the viewer in a world beset by storm.

The work is an engraving, and though it was derived from Rembrandt van Rijn’s 1643 etching The Three Trees, the stormy scene is no masterpiece. It is an eighteenth-century copy, executed by Captain William Baillie in 1758. Baillie was a collector, art connoisseur, and thoroughly amateur printmaker. Born in Kilbride, Ireland, he went to school in Dublin, studied law in London, and spent about two decades living the life of a soldier before deciding that he was, in fact, an artist. Nothing in his past foretold the impact Baillie would have on the art collecting world, both in his own time and ours.

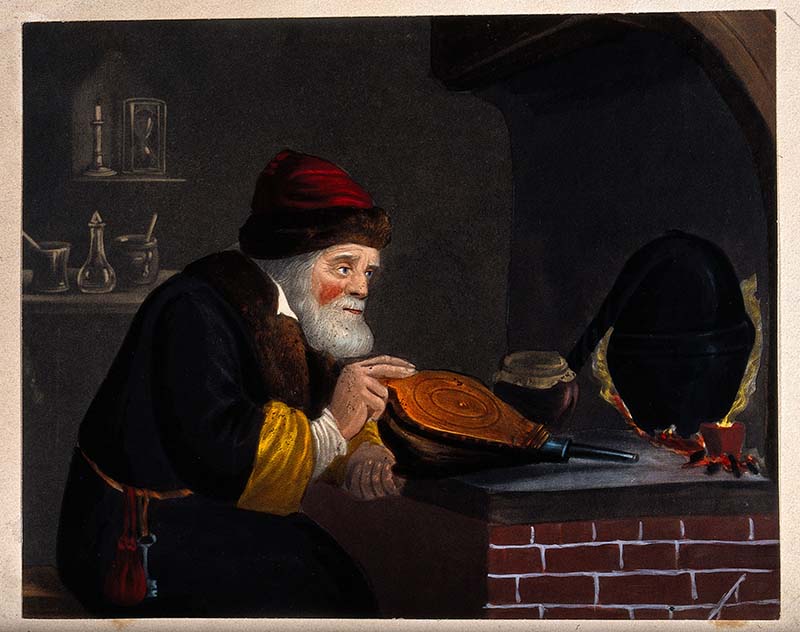

We first learned about Baillie when one of his etchings (Le Paysan sans Souci, 1775) appeared in a little country auction. The framing was nice enough to warrant raising our number, and we were able to scoop it up for a steal, around thirty dollars. The work, a copy after an Adriaen van Ostade original, is decently executed. Immediately, we wanted to know more about Baillie and his world.

Before peeling back Baillie’s layers, however, it’s necessary to begin with what producing and reproducing printed etchings entailed in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, as Rembrandt’s own peculiar practices helped set the stage for Baillie and his contemporaries. More than those of any artist before him, Rembrandt’s creations were constantly evolving. The 2015 exhibition Rembrandt’s Changing Impressions at Columbia University’s Wallach Art Gallery spotlighted how Rembrandt was the first artist to treat the print medium as a means of crafting visibly changing images. By manipulating his copperplate etchings, he achieved printed images that were effectively in flux.

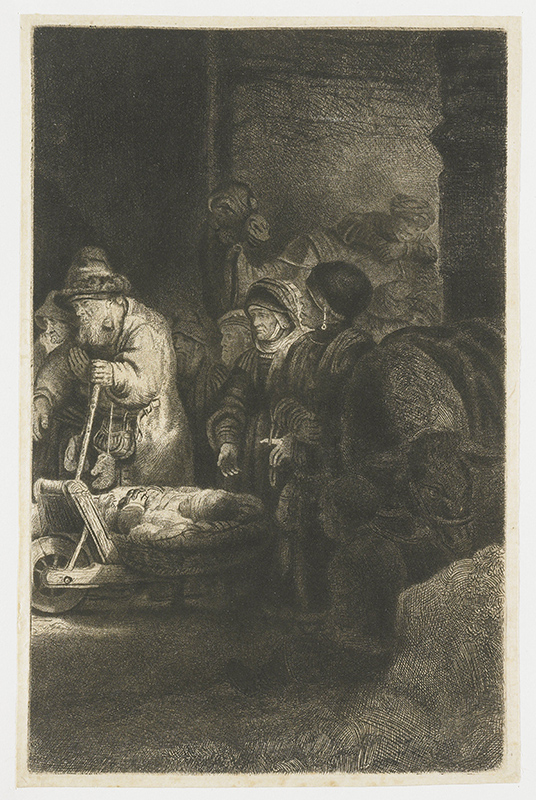

Rembrandt came to be celebrated for continually altering his etchings over the course of his life, creating various “states” of a given work by adding, removing, or altering the elements to produce what was believed to be an evermore compelling image. Deepening or widening the carved lines created more contrast; extensive reworkings—such as scraping off entire sections of plates—erased crowds, people, and even landscapes entirely from the printed product. These alterations were lauded as groundbreaking innovations and were readily welcomed by Rembrandt’s patrons and collectors— especially as any alteration to the original matrix meant that the older prints were now unreproducible, and values increased accordingly.

But Rembrandt did not necessarily make these changes purely to increase the value of his past work— many, as the 2015 exhibition showed, were the outcome of his “intense and restless search for results that satisfied his artistic sense”—and then he died in 1669, leaving the plates to be auctioned off or distributed to whomsoever had the wit, will, and wallet to obtain them, and the skills to maintain them for future use.

Left to right: Second and third states (of six) of Rembrandt’s The Three Trees, 1643, as reworked by Baillie, 1758. Etching, plate tone, and drypoint, each plate 8 ¼ by 11 inches. Metropolitan Museum of Art, Schonhorn gifts.

In the early eighteenth century, a passion for Rembrandt etchings in various “states” had caught on among Continental collectors. Arnold Houbraken (1660–1719), writing in 1718, stated that “the passion was so great at that time that people would not be taken for true connoisseurs who did not have the Juno with and without the crown, the Joseph with the white and the brown face, and other such things.” This widespread enthusiasm was not shared in Britain, where many art critics remained skeptical of the Dutch master’s genius well into the eighteenth century.

The British market for peculiar or rare etchings only came into its own with the transition of aristocrats into “connoisseurs.” As society’s enthusiasm for collecting, rather than merely decorating, came into its own, the purchasing of art pieces ceased to be solely about filling one’s walls. Having one or two very fine pieces of engraving work was no longer enough; one had to have one or two of each version of an engraving. With that, the British gentry threw themselves into a craze that was already reaching a fever pitch.

By the 1760s the passion for prints had British high society well in its grip. The “Madness to have [Rembrandt’s] Prints” was rued by the famed English writer and connoisseur Horace Walpole, who complained that the Dutch artist was “ so well known, and his works in such repute, that his scratches, with the difference only of a black horse or a white one, sell for thirty guineas.”

In this criticism, he was entirely correct. A significant driver in the market for Rembrandt’s engravings was the perceived scarcity of various “states” of prints. Those showing minor alterations created a true scarcity of otherwise reproducible images. This scarcity, and the increased value that came with it, was readily understood by collectors and criminals alike. Indeed, there is significant evidence that many attempted to create “newly discovered” pieces by Rembrandt by cobbling together elements from other prints a century after the artist’s death to feed the ever-expanding demand while, it was hoped, earning huge sums at the auction block. As swiftly as these fakes were created, guides describing how best to spot a fake were written, published, and distributed in collecting circles.

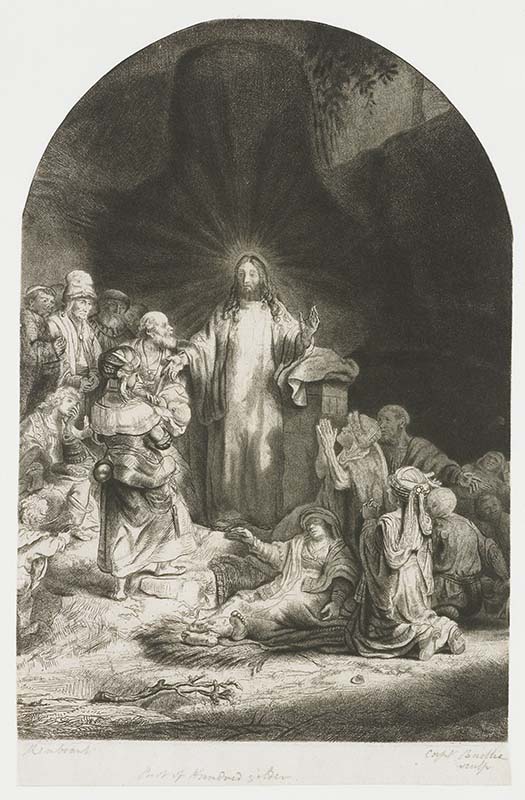

By the mid-eighteenth century, Baillie possessed three of Rembrandt’s original plates, though they were badly worn and in desperate need of restoration, having been used for the century since the artist’s death. To a degree, his efforts to maintain Rembrandt’s legacy were exemplary—even if also bungled a bit on occasion. When, in 1775, he purchased the plate for Rembrandt’s “Hundred Guilder Print” from the painter and engraver John Greenwood (1727–1792), it already showed considerable wear from repeated printings.

The “Hundred Guilder Print,” so named for the price allegedly once paid for a particularly fine example at auction, was considered the masterpiece of Rembrandt’s engravings and was lauded by Houbraken as “the finest print Rembrandt ever made,” on account of the excellence of the chiaroscuro it showcased. Eager to restore the plate to its former glory, and to realize a profit from the prints that would result, Baillie “restored” the plate with what, in 1797, was identified as “such care and intelligence that it takes the eye of an experienced connoisseur not to mistake the impressions from the retouching for those from the untouched plate.” Following its restoration, Baillie proceeded to produce around a hundred copies from the retouched plate—a feasible endeavor, as the copperplates of the seventeenth century were cold-hammered, a process that produces harder plates than the rolled plates used today.

After printing the restored plate, Baillie stepped outside of the realm of restoration and began taking creative liberties that would render any restorer today a persona non grata. In short, he cut the original plate into four pieces, reworked them further, and continued to print these smaller fragments as their own pieces. As we said, he kind of bungled it at the end with that one.

While Baillie played with the plates of many Dutch masters, art historian Andrea Morgan told us that Baillie is elevated from solely an amateur to someone worthy of examination through his contribution to the spread and popularization of reprints and reinterpretations of Rembrandt’s works in the British art market. “Such reprints,” even when poorly executed, “made renowned compositions accessible to modest consumers,” remarks C. Tico Seifert, a senior curator at the National Galleries of Scotland, “while the price for early impressions continued to climb.”

Once Baillie got a taste for his own artistic touch, he did not confine himself to simply reworking plates he could get his hands on. When he wished to produce copies of works without access to the plates, he reproduced the carved matrices out of whole cloth— the best-known example of this is Baillie’s version of Rembrandt’s Three Trees. Baillie’s efforts were amply rewarded. As Seifert attests, Baillie “was able to charge the highest prices ever recorded for an engraver during the period for the various stages of his imitation of The Three Trees.” Yet, Baillie managed to spike his own wheel with posterity when he returned again and again to this plate, altering it in an effort to ramp up the drama and sublime moodiness.

Which returns us to the wild tempest with which this piece began. Baillie began work on his plate of The Three Trees in 1758, and executed six different iterations in the years that followed, each darker and more doom-laden than the last. Parallel to each new print showcasing an ever-more dramatic scene, disapproval of his efforts grew. In time, Baillie would be remembered by many only for the critique of his works levelled by John Thomas Smith (1766–1833), keeper of prints in the British Museum in the early nineteenth century, who, in his Book for a Rainy Day, published posthumously in 1846, called Baillie’s prints of The Three Trees “execrable.”

In the first and second states, the sky retained the pent-up energy of the original—which has been noted as the first time an artist sought to depict the instant of an atmospheric change in an engraving. In the third printing, Baillie added more clouds. Evidently this did not achieve the desired level of dread so, in the fourth, he scratched in a lightning bolt. In the fifth, he doubled down, adding another bolt to the sky. The Rijksmuseum holds yet another, sixth, state with even more lightning bolts. Apparently, when it came to carving cool lightning bolts, too much was never enough for Baillie. The gradual build-up of dramatic elements over the course of many successive printings was financially lucrative. Artistically, it left a lot to be desired and the whole affair leaves one with a somewhat inescapable conclusion: it’s all a bit amateurish.

In producing acceptable imitations on a large scale, Baillie successfully rode a wave of interest that dominated the world of prints and engravings. That wave no longer carries us, and, as Morgan notes, while many large museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the British Museum, have Baillie’s work in their collections, “you’re going to be hardpressed to find many museums that have a William Baillie hanging on their walls.” Original prints from Baillie’s lifetime can often be purchased online, with prices for individual, unframed prints ranging from an accessible $200 to $600. Why, though, should anyone collect pieces by someone museums refrain from displaying and whom we have glowingly recommended as “amateurish”? Because Baillie offers something different. Perhaps if Baillie’s copies are assessed only when held next to a facsimile of Rembrandt’s original, his work does not fare well. Yet, saying Baillie was not as masterful an artist as Rembrandt is hardly fair—who is? Viewed on their own terms, many of Baillie’s works possess an enthusiasm that is palpable and endearingly earnest. Like a traveller’s hard-worn sheets of brass rubbings, they are the scrapbook of a man who has seen beautiful sights and, perhaps over hastily, wished to bring a reflection of them back to others.