It has been said that the Navajo weavings we know today wouldn’t exist without the Spanish, for they introduced sheep and the wool fibers derived from them around the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It has also been said that these same Navajo weavings wouldn’t exist without other tribes, like the Lakota, who traded with the Navajo long before there were white traders clamoring for their wares.

Some even point to the influence of the US government, although this is a particularly brutal connection, as the ethnic cleansing of the Navajo—including their forced relocation—by the federal government in the 1860s amplified the commercial importance of the weavings and expanded Navajo reliance on non- Native traders. And ultimately, many point to these same traders, who have exerted significant influence through their efforts to make the Navajo weavings they buy and sell as commercially successful as possible.

While it is true that all societies are altered and influenced by their interactions with other groups, what all of these arguments overlook is that the Navajo, or the Diné, as they call themselves, lived and wove regardless of intervention, interference, or influence. In the words of Dakota Hoska, assistant curator of Native arts at the Denver Art Museum (DAM), weaving is, for the Navajo, not simply a craft nor an art form nor a form of commerce, it is part of a “philosophical practice” — “a way of looking at the world.”

This is why calling Navajo weavings “art” is culturally complicated. While there are, and have been, outstanding Navajo weavers who identify themselves as artists, there are many who have waved off the identification, concerned that attempts to call Navajo weaving art would only pigeonhole their historic practice. At DAM, Hoska, her fellow curators, and the many who have come before them, have carefully navigated the line between recognizing Navajo weavings (not, she insists, rugs) as art while acknowledging community perspectives and traditions. Frederic H. Douglas, the second curator of Native American art at DAM, spearheaded this initiative starting in 1929 by adding Indigenous pieces to the museum’s collection as art, not, Hoska says, artifact.

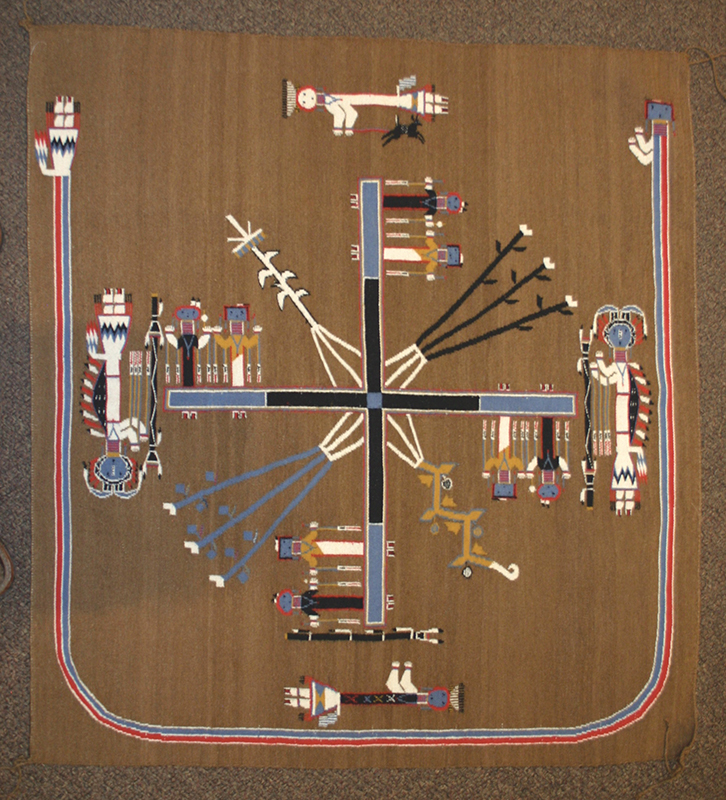

Exhibitions at the museum, such as Red, White, and Bold: Masterworks of Navajo Design, 1840–1870 (2013) have offered opportunities to translate this tension between art and artifact to visitors. By hanging Navajo weavings in an art museum, they are undeniably categorized as pieces of art themselves, but by contextualizing them within a cultural, spiritual, historical, and political reality, they are also living artifacts—evidence of what has come before.

Today, Navajo weavings, whether in private hands or public collections, offer those who view them a complex framework for building an understanding of what happens when cultures and peoples mix together and pull apart, and then come together again, influencing each other with each interaction in ways that are neither universally positive nor unequivocally negative.

Often lost in this pandemonium, though, are the people, mostly women, who for centuries have made these pieces. The process of weaving is arduous and begins long before a loom is warped. The sheep must be bred, raised, and selected for wool color. They then must be shorn, the fleece cleaned, and the wool carded, spun—a process still done by hand—and, if applicable, dyed. Finally, when the yarns are ready, the weaving can commence. Each weft is placed carefully to form a pattern. Whether the final product impresses for its simplicity or its complexity, the process is the same. Many weavers still do each of these tasks themselves, from raising lambs to spinning, or as part of a small, interdependent group.

For most Navajo weaving collectors, the first contact with the work comes after it has been purchased by a trader. Since the turn of the twentieth century, nearly all of these traders have been non-Native. Both a translator of style and a broker of value, traders have undeniably influenced the dominant patterns and designs, both by directly communicating their preferences to the weavers with whom they work and by pressing buyers to see value in the designs they themselves enjoy.

Jackson Clark, founder of Toh-Atin Gallery in Durango, Colorado, is a descendant of this trader tradition. His maternal grandfather, whom Clark jocularly refers to as “one of those guys who came out west to die of tuberculosis but didn’t do it until he was ninety-six,” ran a trading post on the northern end of the Navajo Nation. Clark’s father, too, became a trader, albeit more or less by accident. The story is wonderfully complicated and colorful, and we encourage visitors to Toh-Atin to ask to have it told, but a very condensed version is that Clark’s father, an employee at Pepsi-Cola, was tasked with getting more of the company’s products into the reservation and surrounding communities. The stores were short on cash to buy merchandise, so he traded sodas for weavings and then sold the weavings to obtain the money owed to Pepsi-Cola. Clark family vacations often entailed filling up a car with weavings and driving from place to place searching for buyers. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Jackson Clark caught the bug.

Stories of traders’ involvement with Navajo communities often run eerily close to what could be called exploitation. Many of these stories appear romantic if not for the power imbalances at play. In a 2010 video segment by Voice of America News about the Toadlena Trading Post in Newcomb, New Mexico, and the weavers of the region, a weaver is quoted as saying, “whenever I run out of food or something, I always ask [the trading post owner] for money. With my rug,” she says, pointing to the weaving she is working on, “I’ll pay you back.” This is presented as a heartwarming symbiotic relationship. However, when you account for the fact that contemporary Navajo pieces sell through traders for hundreds to tens of thousands of dollars, it gives one pause to think that such skilled and sought-after artisans would regularly “run out of food” for lack of funds at all.

Jackson Clark works to avoid this exploitation by selling both antique and contemporary pieces, but in different ways. Antique pieces at Toh-Atin are sold on consignment, which keeps capital available for Clark to invest in the preservation of the practice of weaving. “We could make a lot more money,” he says, “if we only bought old things.” But that would be a self-defeating strategy. Today’s weavings are, after all, tomorrow’s antiques.

When shopping for antique Navajo weavings there are myriad designs and styles, but the most commonly encountered term and one that needs some explanation— is “chief’s blanket.” The Navajo traditionally lived in fairly small groups with complex networks of social and political ties. They did not have “chiefs” in the strict sense of the word, but they traded their weavings with other Natives, such as the Plains Indians, who did. Only the chiefs could afford the finest, most tightly woven, and thus warmest and most waterproof, weavings, so they became known as chief’s blankets.

There are three distinct types of chief’s blankets: Phase 1, Phase 2, and Phase 3, but Hoska is keen to emphasize that “phase” refers to form and materiality more than to date of origin. A Phase 1 chief’s blanket, featuring horizontal bands of white, brown, blue, or red, may well be older than a Phase 2 chief’s blanket, in which rectangular shapes were added to the design, but a Phase 1 blanket can just as easily be newer than a Phase 3 with triangles. While a Phase 1 blanket woven today may be less valuable on the market than a Phase 1 blanket woven between 1800 and 1850, the more contemporary piece is no less authentic. “Reproduction” is not a word that can be applied to Navajo weaving, as the artistic practices are of a continual and unbroken tradition.

A word that can be applied is “expensive.” Large vintage and antique Navajo weavings in good condition start at more than $1,000 and skyrocket from there. In 2012 an exceptional nineteenth-century Phase 1 blanket with stripes of brown, white, red, and blue, realized $1.8 million at John Moran Auctioneers. While this price isn’t common, it is certainly eye-watering.

If buyers want any chance of a more modest piece surviving long enough to reach anywhere near that value, Clark is insistent that they must learn how to care for their textiles. Walls are safer than, say, the floor, and it’s important to place pieces away from direct sunlight and to turn them frequently to reduce fading. Turning a weaving is also important because it discourages moths—perhaps the greatest danger to any natural textile. If you buy a weaving and are not absolutely certain it was recently cleaned, have it washed—not dry-cleaned—to destroy any hard-tospot critters before they devour your investment.

However, one must try to avoid becoming so fixated on preservation that it derails engagement with the piece. While talking to Hoska, we were intrigued by the idea of weaving as a “grounding art” for the Navajo—a practice that roots them in place while providing a sense of structure and strength. Those drawn to Navajo weavings are often in search of just such grounding. They crave an authentic truth that Navajo weavings offer. But with the art of weaving in peril today, it is by no means assured that this unbroken tradition of tradecraft will survive for the collectors of tomorrow without careful stewardship and patronage. It is important that dedicated enthusiasts buy carefully, invest wisely, and consider supporting living weavers and the traders who respect them.