How national flags have come to represent all that is good and lawful in modern society.

One of the great developments of the early modern period was the creation of modern nation states. The long and often bloody paths by which many medieval communities became countries was an arduous one and, for many peoples, the struggle to create nations from the ruins of former, polyglot political entities was intensely formative of their later national character. Often, an easily consumable visual symbol became a potent reminder of these struggles for independence and self-determination.

The concept of a national flag arose in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, largely as a result of the American and French revolutionary wars. As the scholar Krzysztof Jaskułowski has written, the leaders of the French Revolution “attached great importance to the creation of a new symbolic universe” in order to legitimize the novelty of the new political and social order they were seeking to create. When, in 1789, the embattled Louis XVI was threatened by the Parisian mob that had marched on Versailles, the royal family was only able to escape with their lives when the king agreed to make a public demonstration honoring the revolutionary cockade, the iconic pleated ribbon of blue, white, and red, in front of the crowd.

Banners, standards, and coats of arms had long been used as symbols of power, even sometimes standing for abstract notions of political authority. This revolutionary episode, however, illustrates a fairly significant conceptual leap. The revolution was not personified in any one individual, or even any grouping of men and women—it was not found in the person of the king, nor in the National Assembly, nor yet in the people of Paris. The revolution was simultaneously incorporeal and also able to be made manifest through ornament and symbol. The origin of the three colors was no longer the central narrative. The composed image had become an entity all by itself.

The tricolor of the French revolutionary cockade in time became the flag of France. A symbol that had drawn on the traditional colors of the city of Paris and been fussed over by the marquis de Lafayette had transformed from an expression of a feudal system into the manifestation of a modern, abstract, self-determinative nation. The tricolor was sacred, as the idea of France was sacred. Woe to he who would desecrate the symbol, or the spirit, of the nation.

The potency of such symbols was as true for the young United States as it was for France, although the path to the final product was a bit less direct for the former colonies. The first flag employed by the United States is known today as the Continental Union flag and was composed of a British Union flag and thirteen red and white stripes. American sailors first hoisted the Continental Union flag on the warship Alfred while that ship was in harbor in Philadelphia on December 3, 1775. It was a de facto national flag, but the prominent use of the British Union in its design would soon drive the Congress to commission a flag more appropriate for an independent republic. When the Flag Act was passed in 1777, the new national emblem was born. It was not, however, described with a great deal of exactitude. The act states: “Resolved, That the flag of the thirteen United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” If any group needed the descriptive assistance of a graphic design team, it was the Second Continental Congress.

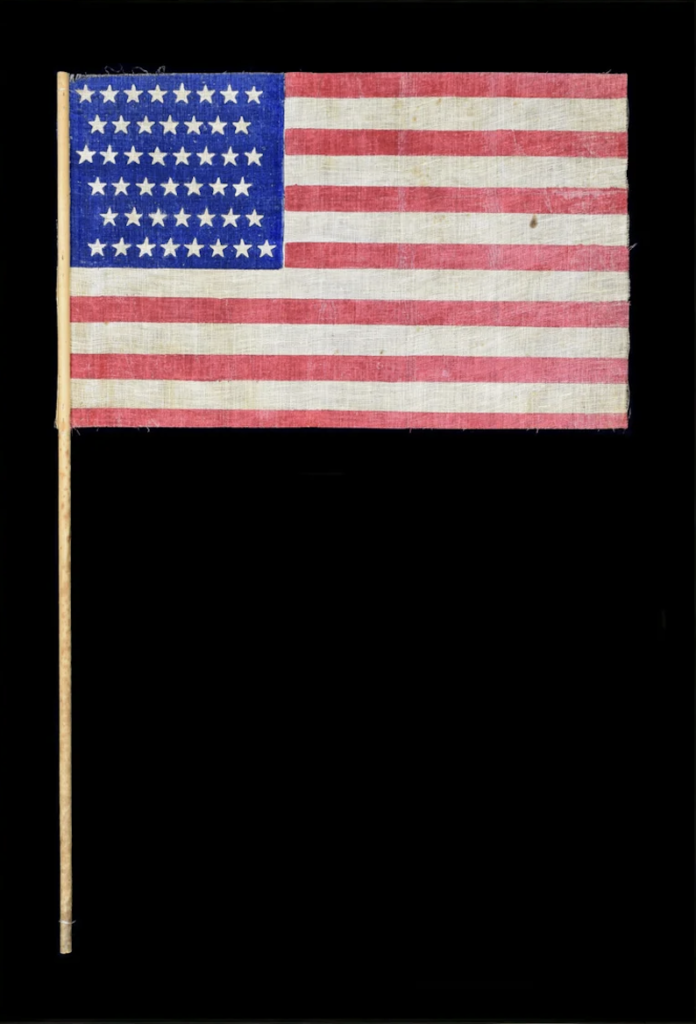

The interpretive vagaries of this language of a “new constellation” allowed for an incredibly creative—and sometimes quite bizarre—period of guerilla American flag designs. It was a free-for-all until well into the late nineteenth century. The profusion of Union symbolism during, and in the aftermath of, the Union victory in the Civil War began the process of homogenizing Americans’ sense of how the flag “ought” to look. The matter of the exact design of the flag was not actually concretized, though, until President Taft’s executive order of 1912 that prescribed the measurements and placement of the elements on flags purchased by the government of the United States for official use. Once these were codified, everyone else more or less followed suit.

The period before this standardization, that free-for-all era, is when the really interesting and collectible American pieces arise, says Heather Bonsell of Bonsell | Americana in Hillsdale, Illinois. “Before 1912, makers were at liberty to do something of their own interpretations of the flag. There were a lot of different, unique interpretations, especially of star patterns.”

It is extremely rare for national symbols to expand and contract to reflect the number of parties in the confederation. From the outset, the decision by the Continental Congress and then the Confederation Congress to have the flag change with every state admitted is a unique and powerful one, though it may not strike us as such today. The kings of France were not adding and subtracting fleurs-de-lys for each duchy or principality that paid fealty to the king in Paris. The decision to allow new American territories to organize themselves and petition for statehood on an entirely equal footing with the original thirteen was radical in its day. That their inclusion would be reflected through an alteration to the nation’s flag was a striking performance of that egalitarian ideal.

This aspect of American nationhood was, indeed, performative, both in the additions and the attempted subtractions. Bonsell has had a number of flags pass through her hands that were created to celebrate the secession of one or another of the Southern states at the outbreak of the Civil War. When one considers that the stars on many flags in this period were sewn on by hand, that becomes an incredibly personal act of protest—but also of celebration. Some flags, such as one made for Kansas’s entry into the union, show the addition of subsequent stars tucked between the other rows, offering a wonderfully personalized acknowledgment of the changing status of the nation.

As with many collectibles, provenance, condition, rarity, and interesting elements all play a role in determining value and collectability of a flag from any nation—but especially those of the American variety. These quirky Old Glories enjoy popularity in both the fields of patriotic ephemera and the historic Americana markets. Bonsell notes that most collectors “are buying the flags to display them.” Size, then, also comes into play. Massive, car-dealership-size historic flags suffer at the auction block even when outstanding, as few have the wall space to hang them. But smart looking, interesting examples, especially when correctly mounted using archival materials can sell from between $5,000 and $50,000.

Every few decades, the United States goes through a reexamination of its principles and beliefs surrounding the flag and its position in society. In 1942 a decades-long call to action resulted in the promulgation of the United States Flag Code, which is a legal document that lays out the proper use of the flag of the United States. Violations of the code are not punishable offenses, but many hold the improper treatment of the flag to be akin to kicking puppies or refusing to call one’s mother on her birthday, which is to say, they are held to be a thing done only by evil people. At times, this can all come across as a bit silly. After all, who will really be upset if a flagpole mounted to the bed of one’s truck is set to one side, rather than being mounted directly in the center as the flag code instructs? Is it really so terrible to wear a bikini depicting the flag? All these things are strictly regimented by the flag code.

Yes, to a certain degree, imbuing a rectangle of red, white, and blue fabric with the hallowed sanctity of a holy relic borders on the ridiculous. And yet, the bands that tie us each to one another are only as strong as our shared beliefs. In this interpretation, we must be as careful with our flags as we are with our ballots and our right to protest, because they are all expressions of the intangible idea of the national community. May it continue to grow and change with the people, as our Founding Fathers intended.