Miniature paintings in watercolor on ivory of a single eye were introduced in France and quickly became a fad in Great Britain in the late eighteenth century, later transferring, in a modest way, to the United States by century’s end. They came to be known as “lover’s eyes”—intensely private objects, usually of the giver’s eye presented to a loved one. The disembodied eye allowed the viewer to gaze upon the object of his or her affection, known only to them, and then, actively, the gaze was returned.

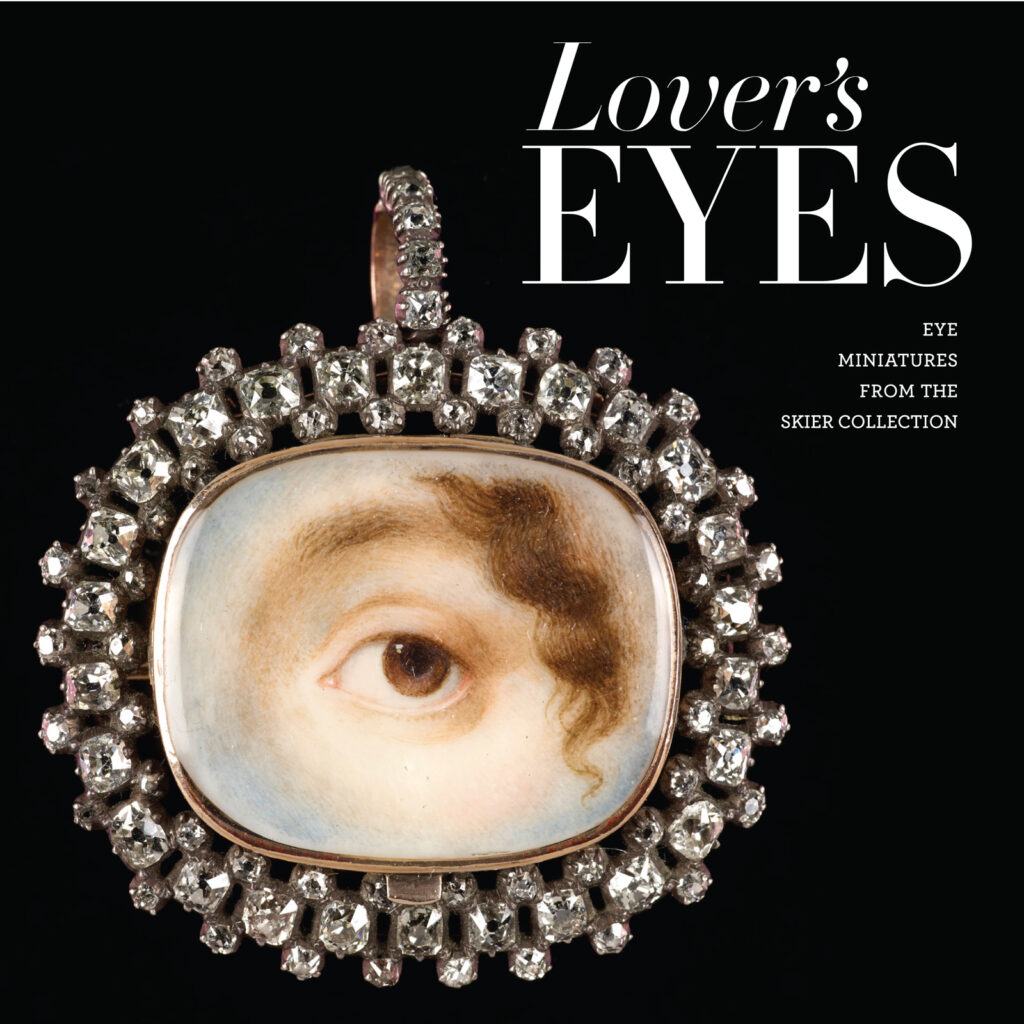

The recently published Lover’s Eyes: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection provides a revised and expanded version of the 2012 exhibition catalogue The Look of Love: Eye Miniatures from the Skier Collection, a show held at the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama. Nan and David Skier—he happens to be an eye surgeon—came upon an eye miniature at a Boston antiques show many years ago and became enamored, putting together one of the most important collections of these mesmerizing objects that have received little scholarly attention until recently. (The most comprehensive exploration of the subject is Hanneke Grootenboer’s Treasuring the Gaze: Intimate Vision in Late-Eighteenth-Century Eye Miniatures, published by the University of Chicago Press in 2012.)

Elle Shushan, who has devoted her career as a scholar and antiques dealer to the broad-based study of watercolor miniature portraits, serves as the volume’s editor, which includes six essays by her, Graham Boettcher, and Stephen Lloyd. Lover’s eye miniatures are an elusive and captivating subcategory of the miniature portrait, and exhibit distinctive characteristics and visual interactions that differ from more standard portrait miniatures. The book includes a catalogue of more than 130 examples from the Skier Collection.

Chapter one, “The Artist’s Eye,” provides an overview of the first appearance, in the late eighteenth century, of lover’s eye miniatures, which were exchanged among lovers, friends, and family members. Chapter two explores the emergence of the fad when the flamboyant Prince of Wales was refused permission by his father, George III, and by British law, to wed his mistress, the widowed (and Catholic) Mrs. Maria Fitzherbert. The prince commissioned Richard Cosway, the popular court miniature portraitist, to paint his eye in miniature, and later one of Mrs. Fitzherbert, thus launching the craze.

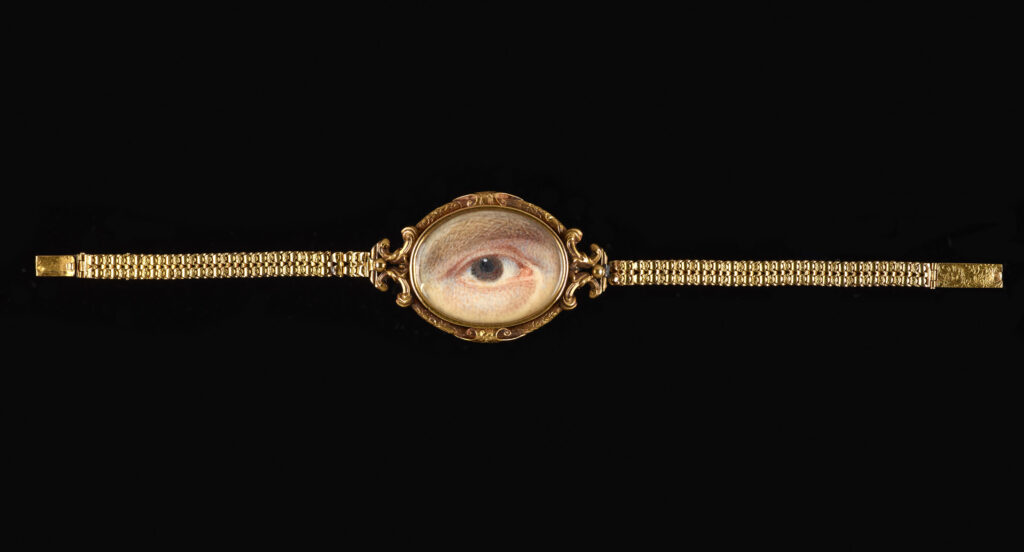

The extraordinary settings for eye miniatures were intended to allow them to be worn as jewelry, often close to the heart. They were set into metal cases, rings or bracelets, and boxes, and included hairwork, for mourning jewelry, all chronicled in chapter three, “Symbol and Sentiment: Lover’s Eyes and the Language of Gemstones.” Chapter four “Floriography” presents a series of eye miniatures that use flowers to surround eye portraits, providing an added significance and symbolism. An important discussion of later revivals of eye miniatures, including their resurgence in the mid-nineteenth century during the reign of Queen Victoria, as well as outright fakes, is explored in chapter five, “Fake or Fashion.” And finally, chapter six, “Love Never Dies,” reveals the phenomenon’s survival into the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries.