With the word “counterculture” in the title, you might be tempted to hum “Are you going to San Francisco?” and stick a few flowers in your hair even before opening this illuminating volume. Indeed, the “whole generation with a new explanation” referenced in the song lyrics stood for the baby boomers who pulled away from the conformity of mainstream America and pointed themselves toward the open road and an independent life.* Hardly a simplistic term, “counterculture” embraces a multiplicity of ideas in a contentious era that included the civil rights movement, anti-war marches, budding environmentalism, the nascent gay rights movement, and second-wave feminism. What effect did all these developments have on studio jewelry? As charted in this book: quite a bit and not very much. The latter was due to the prevailing academic emphasis on technique and composition at university metalsmithing programs, which left little room for personal expression. The era produced quantities of beautiful and well-designed cast, forged, chased, and enameled ornaments. Jewelry that expressed opinions, or point of view beyond pure aesthetics, was in the distinct minority.

(Untitled) Drain brooch by Ken Cory (1943–1994), 1968. Tacoma Art Museum, Washington, gift of the Estate of Ken Cory, © Beverly Cory; photograph by Doug Yaple.

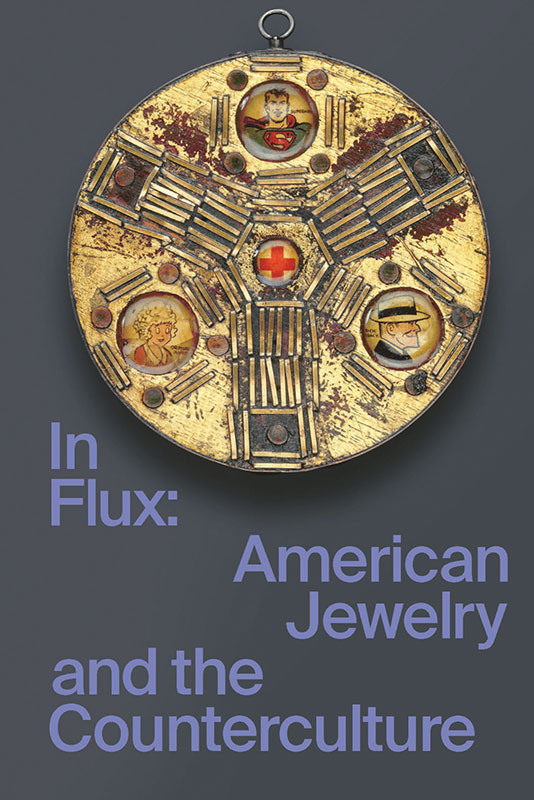

Come Alive, You’re in the Pepsi Generation by J. Fred Woell (1934– 2015), 1966. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, gift of Kathleen Kriegman.

A hardy few souls—including thirty-five major artists— are the subjects of this well-illustrated volume, yet their small numbers are in inverse relation to the outsized influence their work would exert on the field. These artists reached for their jeweler’s tools when confronted with newspaper headlines and wartime photographs of My Lai, the carnage at Kent State, and the Watergate scandal, among other national traumas. Interviews and telling anecdotes add depth to the reader’s understanding of the decision-making process behind the creation of these objects.

J. Fred Woell best exemplifies artists working in this frame of mind. The authors document his artistic journey from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where he devoted himself to jewelry making in its traditional sense of technique and skill, and was encouraged by his teacher, Arthur Vierthaler, to experiment with nonprecious materials. It follows Woell as he travels to New York to visit The Art of Personal Adornment at the Museum of Contemporary Crafts (today’s Museum of Arts and Design). There he was struck by the use of found objects and by the realization that many examples were crude, but still inventive and affecting. This epiphany led to Woell’s creation of collaged objects using mixed mediums such as advertising imagery, photographs, and objects like the spent bullet casings in his 1966 landmark work, Come Alive, You’re in the Pepsi Generation, an ironic indictment of American life during the Vietnam War. “Improvisational” best characterizes the jewelry of Don Tompkins, who assembled disparate objects to honor celebrated figures like jazz pianist Fats Waller and professional billiards player Minnesota Fats. In 1970, following the Kent State shooting of students by the National Guard, he combined several elements— the now-iconic photograph of fourteen-year-old witness Mary Anne Vecchio, with her hands outstretched in horror, mirrored by a cast of Mickey Mouse in the same gesture, combined with the words “Nixon” and “Bring Us Together.” For artist Joyce Scott, it was grief over the Jonestown massacre of 1978 and the mass suicide engineered by the cult leader Jim Jones that prompted her to create The Double Cross.

Nixon (Bring Us Together) by Don Tompkins (1933–1982), c. 1970. Collection of the Tompkins family, © Estate of Don Tompkins; photograph courtesy of Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

Electronic Oxygen Belt Pendant by Mary Ann Scherr (1921–), 1974. Museum of Arts and Design, gift of Mary Lee Hu, through the American Craft Council, © Scherr Family; Taylor photograph, courtesy of Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

Consummate craftsmanship, found objects, and a subversive sense of humor characterize the work of Ken Cory and his friend Leslie LePere. Working together as the Pencil Brothers, they produced amusing work that often contained double entendres. Cory’s (Untitled) Drain brings disparate materials together in a curiously sensual tease.

Some female studio jewelers found their true north by exploring feminist perspectives. Among them were Merrily Tompkins, whose merkin-covered purse was designed to shock, and Nancy Worden, whose subversive Initiation offered a more thought-provoking experience of femininity using parts of pink hair curlers, pills, and a wishbone. The cyclical nature of social consciousness in the arts is worth noting here. Just as the arts and crafts movement was founded on this basis, so too were the works produced by these remarkable nonconformist artists of the Sixties and Seventies. Here in the twenty-first century we are once again undergoing a sustained level of activity in this realm. It is worth remembering those who helped to lead the way.

Come Alive, You’re in the Pepsi Generation by J. Fred Woell (1934– 2015), 1966. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC, gift of Kathleen Kriegman.

The Double Cross, from the Jonestown Massacre series by Joyce J. Scott (1948–), 1980. Philbrook Museum of Art, Tulsa, Oklahoma, © Joyce J. Scott; photograph courtesy of Arnoldsche Art Publishers.

* Title and quotation from “San Francisco (Be Sure to Wear [Some] Flowers in your Hair), lyrics by John Phillips, vocals by Scott McKenzie, released 1967.