Since her death in 1944, Florine Stettheimer has been celebrated, ignored, and rediscovered more than once. Important exhibitions and critical appraisals both here and abroad over the last decades should have settled her reputation, and yet a whiff of advocacy and argument often lingers when her name comes up. It is possible that despite impressive champions beginning with Marcel Duchamp, who organized the Museum of Modern Art’s exhibition of her work in 1946, MoMA’s first full retrospective dedicated to a woman, her art has been misperceived as too approachable for a modernist, her subject matter too sweetly recherché.

Then, too, there is the way in which the art market can deform a reputation: Stettheimers rarely come up for sale because she made it impossible to buy her work during her lifetime, and her family donated most of it to public institutions after her death. Few sales = diminished significance; that’s the art market’s contribution to art history. A vast and handsome new biography by Barbara Bloemink, a longtime Stettheimer scholar, should at last put an end to such dithering.

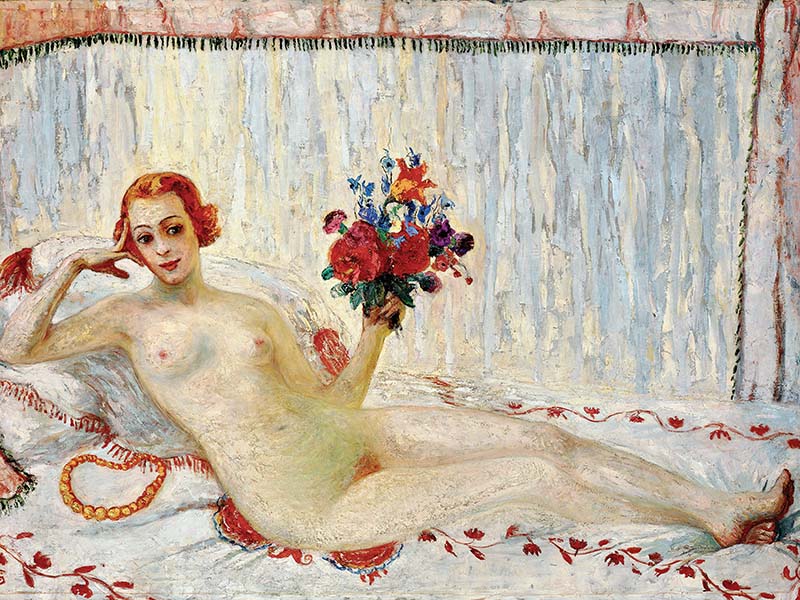

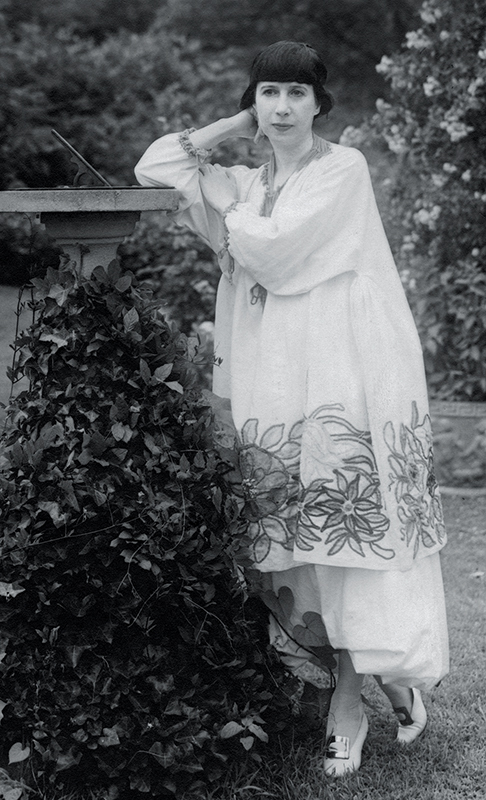

The cover image of the book, a nude self-portrait done around 1915 or ’16, before Stettheimer had arrived at her distinctive style, puts readers on notice: we are in for a bold reading of an artist who could subvert the great nudes of art history, from Titian’s Venus of Urbino to Manet’s Olympia, with an image of herself that is neither erotic nor passive but simply matter of fact, even somewhat amused. To be clear, the painting was not identified as a self-portrait until the 1990s, nor could it have been, given the artist’s milieu: until her final years she never left her wealthy upper-middle-class Jewish family of mother and two sisters, where, despite family friendships with artists and writers of several classes and sexual persuasions, personal decorum was preserved and a proper woman did not appear in public without her gloves.

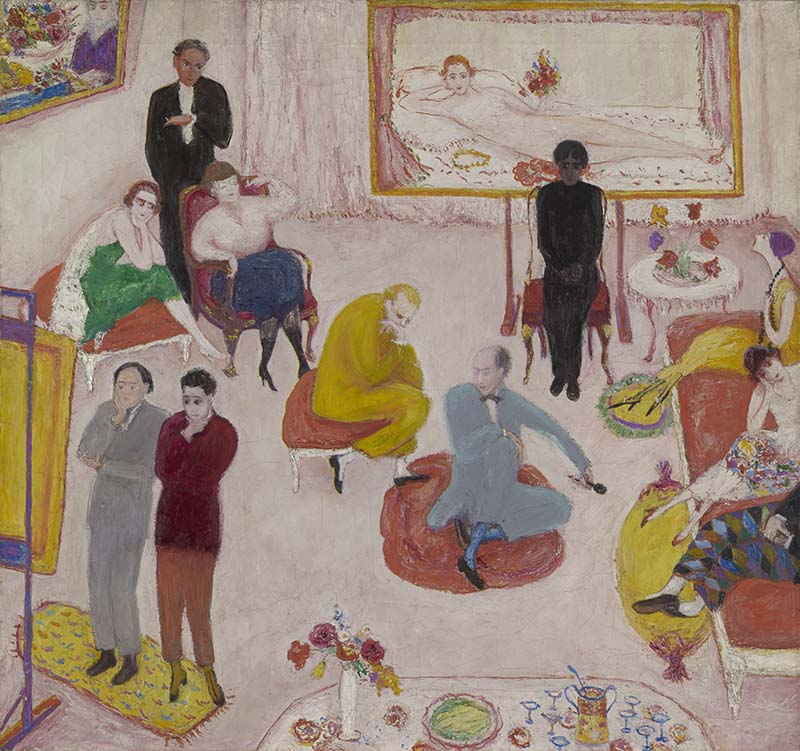

So how did she do it? How did she carve out her pathbreaking and deceptively simple style while never, so to speak, leaving home? As much as anything else, the success of Bloemink’s book lies in the way she weaves together biographical information with close analyses of the work to answer that question. It is riveting reading, some of it quite amusing. Stettheimer’s portraits as well as her depictions of her social circle are not at all what at first glance they seem. In Studio Party (Soirée), for instance, a depiction of a gathering of friends to view a Stettheimer painting, catches them instead in various self-absorbed poses, as the artist, seated on a sofa, casts a cold eye on the scene. Except for one guest, a woman, they all seem oblivious to the shocking fact that another painting, the one on the wall behind them, is in fact the artist’s nude self-portrait. It is possible to be a feminist artist without specific feminist content, and, by and large in my view, that is what Stettheimer was. Bloemink would undoubtedly disagree, but here she is right, we do have what amounts to a fine feminist joke.

Stettheimer’s friend Duchamp freed artists from canvas and paint with his readymades —the fountain/urinal signed R. Mutt, and so forth. He may well have emboldened Stettheimer, too. Even though she stayed with paint and canvas, she did not place them in the traditional hierarchy above her lifelong interest in fabrics, feathers, and cellophane, which culminated in her set designs and costumes for the original production of Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein’s opera Four Saints in Three Acts. Bloemink is especially good at detailing both the artistry and the social history of this epochal event, the first time Stettheimer achieved any substantial public recognition, even as her family remained cool to it all.

It is not easy to keep the life story flowing while delivering meticulous analyses of the art. But Bloemink does this, while also repairing the damage done by an eccentric and reductive early biography the Stettheimer family commissioned from the florid film critic Parker Tyler, who, to appropriate James Joyce, was a bit too Jung and easily Freudened. Among other diminishments, he explained her life and art as the consequence of a narcissistic wound inflicted by a one-woman show of some early work at the Knoedler gallery in 1916 that sold nothing. Was she mortified? Possibly, but Bloemink’s biography allows us to see how she put that disappointment behind her to create her idiosyncratic art; it was a heroic journey and it animates this book.

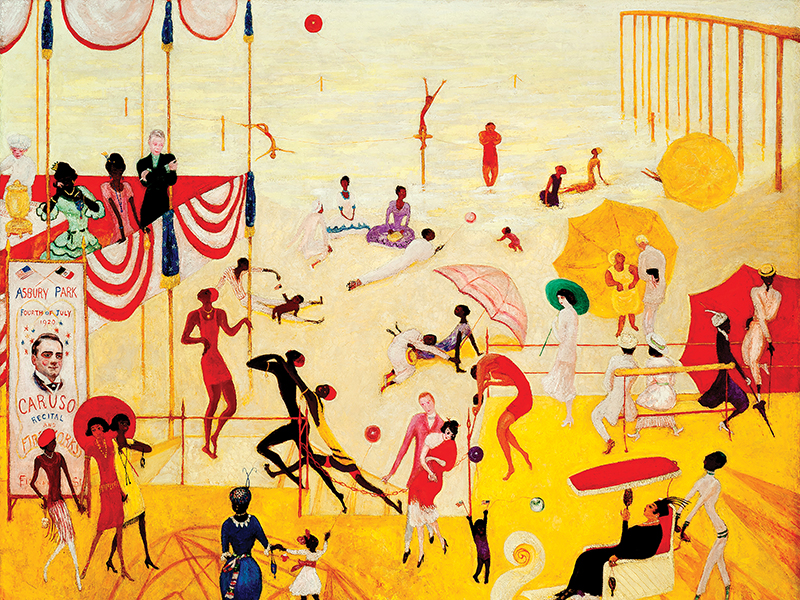

I’m not sure it adds to the artist’s stature to overemphasize her feminism as the publicity for the book does. She doesn’t need that any more than artists like Eva Hesse or Cindy Sherman do. Nor am I entirely persuaded by the discussion of race. Yes, she was a good friend of Carl Van Vechten, the white champion of Black culture who introduced her to many of Harlem’s important cultural figures. Her excellent painting Asbury Park South (1920) depicts African American beachgoers with care and a celebratory brio unusual at the time, but her Beauty Contest: To the Memory of P.T. Barnum (1924) includes worn racial stereotypes. She was for the most part more enlightened on the subject of race than was typical at the time, and I think the matter can be left at that.

After her death. her sister Ettie razored out large swaths of Florine’s journal and destroyed many of her poems. (Bloemink sprinkles the surviving verse throughout the book much to my delight.) Why the censorship? Florine was not a nice gal, you can be sure of that, and Bloemink doesn’t disguise the fact, but she doesn’t serve up any excuses either. Read her book and you will see how Florine Stettheimer became what she became while more or less remaining who she was supposed to be. A neat trick women no longer have to perform . . . at least I hope they don’t.