Making It Modern: The Folk Art Collection of Elie and Viola Nadelman by Margaret K. Hofer and Roberta J. M. Olson (New-York Historical Society in association with D. Giles). 376 pp., color and b/w illus.

There’s nowt so queer as folk,” according to the venerable English comment on the vagaries of human personality. Indeed, when the Polish-born American sculptor Elie Nadelman and his wife Viola Flannery married in 1919, the exceptional variety of objects that we now categorize as folk art were only beginning to be recognized as worthy of serious collecting in America.

Though the Nadelmans referred to their ac quisitions as “folk art” from the beginning of their collecting activities in 1920, the term itself didn’t enter widespread use until the next decade.

The Nadlemans had considerable money to spend because Viola had been left a sizeable estate by her first husband, and they started their collection by purchasing objects to furnish their houses. Among their first significant acquisitions were a Romanesque Italian column and an Italian Renaissance Solomonic (i.e. twisted) column, a classical marble head, and a Flemish carved wood relief, all purchased from the New York dealer Joseph Brummer, whose stock ranged from antiquities and pre-Columbian objects to works by Matisse, Brancusi, Picasso, and Man Ray. In the meantime, Nadelman was succumbing to the lure of Americana offered by the dealer Charles Woolsey Lyon, including a naive portrait by the nineteenth-century American Joseph Whiting Stock, a pewter and glass candle reflector, and other pieces.

The couple spread their acquisitive nets over a wide range of categories, from medieval tapestries to rocking horses, medicine bottles, quilts and samplers, paintings, carvings, antique dolls and toys, and even so-called tramp art. Within a few years their swag overflowed both their double town house in Manhattan and their Victorian country retreat in Riverdale, New York. So in a separate building on their Riverdale estate, they opened their Museum of Folk and Peasant Arts to allow the public access to their treasures. The museum contained almost fifteen thousand works spanning six centuries and thirteen countries (Americana was only part of the story). By 1937, however, hit hard by the Great Depression and financially drained by their liberal spending, the Nadelmans were forced to close the museum. Fortunately, most of their collection was purchased en bloc by the New-York Historical Society, where it still resides.

This impressive catalogue, published to accompany an exhibition currently at the Albuquerque Museum (through November 29) and traveling to the New-York Historical Society and the Addison Gallery of American Art in Andover, Massachusetts, is the first in-depth study of the Nadelmans’ collections. Featuring seven scrupulously researched essays—including an insightful look at “Viola Nadelman as a Collector” by the couple’s granddaughter, Cynthia Nadelman—the book provides an inviting overview of the collection’s sophistication and breadth.

The lavish illustrations emphasize what a matchless trove might have been dispersed in 1937 were it not for the historical society’s farsightedness and they demonstrate the range of the Nadelmans’ appetites: English and American ceramics, chalk ware, European and American colored glass, band boxes, cooking utensils, paper dolls, painted metal toys, portraits, elegantly painted fire engine cases from President Van Buren’s day, needlework, glorious examples of calligraphy and fraktur. A section featuring selected sculptures by Elie Nadelman lets the reader examine his work in the context of his collecting. Moreover this selection provides additional Nadelman works to consider while reading Barbara Haskell’s thoughtprovoking, illustrated essay, “Nadelman and Folk Art: The Question of Influence.”

The Frick Collection: Decorative Arts Handbook by Charlotte Vignon (Frick Collection in association with Scala Arts Publishers). 149 pp., color illus.

The renown of the Rembrandts, Fragonards, Turners, Whistlers, and other paintings of the Frick Collection tends to overshadow the fineness of the furniture, bronzes, porcelains, and other decorative arts that Henry Clay Frick collected with the same seriousness of purpose as he did old masters. Surprisingly, however, it was only in 2007 that an endowed position was created for a permanent decorative arts curator. And since assuming this position in 2009, following a two-year fund-raising and search period, Charlotte Vignon has focused much needed attention on this aspect of the Frick Collection by initiating a series of important exhibitions, most recently a show dedicated to Antoine Coypel’s eighteenth-century tapestry designs for Gobelins inspired by Miguel de Cervantes’s Don Quixote. The Frick Collection: Decorative Arts Handbook is her latest contribution, and a welcome one.

Not an exhaustive catalogue, it is a detailed summary of the museum’s important holdings, and a perusal of the table of contents may well open the eyes of many who have overlooked this aspect of the Frick experience: each of the eight chapters covers a specific field—enamels, clocks and watches, furniture, gilt bronzes, European ceramics, Chinese porcelain, silver, and textiles. Michael Bodycomb’s splendid color photography captures the overall beauty of each work, whether of porcelain, precious metal, wood, or other medium. Moreover, several choice images allow us to examine in detail their surface richness in a way that would be impossible for visitors to do in person. For example, one reveals the very high relief carving of the Apollo and Daphne passage on one of twin sixteenth-century Italian walnut marriage chests (cassoni). Another emphasizes details of chasing, flat-chasing, and post-casting cutting, engraving, and related ciselure on a George II silver-gilt covered bowl by Paul de Lamerie, thereby highlighting the meticulous artistry that this masterly Huguenot goldsmith brought to English silver.

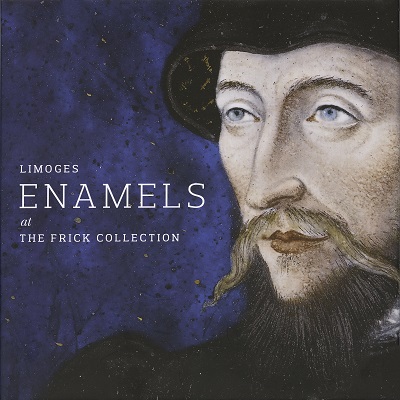

Limoges Enamels at the Frick Collection by Ian Wardropper with Julia Day (Frick Collection in association with D. Giles). 80 pp., color illus.

Complementing the Handbook is the equally handy new book on one of the most exquisite facets of the Frick’s decorative arts holdings, its exceptional collection of Limoges enamels. Enamels are essentially miniature paintings—of sacred or mythological scenes, or portraits— fashioned of colored vitreous powders applied to a copper, gold, or silver support and fired in a kiln. During the Middle Ages and Renaissance enamels were used in jewelry, mounted on furniture and ecclesiastical objects, and fashioned as stand-alone portrait and devotional plaques.

Prior to assuming the directorship of the Frick, Ian Wardropper was chairman of the department of European decorative arts and sculpture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he oversaw major exhibitions of French bronze sculpture and pietra dura, among others. Together with the Frick’s associate conservator, Julia Day, who is an enamel specialist as well as an enamellist in her own right, Wardropper has written a fascinating book on this intimate subject.

His introduction summarizes the history of the Limoges collection—the specific pieces were selected for Frick in 1916 by the great English dealer Joseph Duveen from the large collection of the late J. P. Morgan, who had died in 1913, and they represented the Morgan collection’s cream. Wardropper offers detailed discussions of the techniques used to create medieval and Renaissance enamels, as well as the illuminated manuscripts, stained glass windows, and engraved images that inspired their designs. Further discussions explain the derivation and significance of the religious and mythological subjects depicted by the enamels, as well as the original decorative function of these small masterpieces. There is a concluding discussion of the artists of Limoges and their workshops.

Overall this book is as jewel-like as its subject, thanks to Michael Bodycomb’s superb, detailed photographs. Both Frick volumes represent valuable additions to the general decorative arts literature.

Common Wealth: Art by African Americans in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston by Lowery Stokes Sims (MFA Publications). 256 pp., color and b/w illus.

Beginning with its adroit title, playing on Massa chu setts’s official status as a commonwealth, this survey of the MFA Boston’s important collection of African-American art offers a significant record on many fronts.

Instead of a predictable chronological approach, the book is organized by themes central to African-American life—indeed to all American life. The initial theme is “Vessels of Memory.” Starting with handmade antebellum jars and jugs, some completely utilitarian, some embellished with grotesque faces that suggest a cross between traditional West African masks and the weird fantasy vessels produced by the Martin Brothers in England, each is physically symbolic of the potent force of memory for African Americans, displaced from their roots. Equally symbolic of memory is Mary Jackson’s exquisite Basket with Lid (1992), its design descending from those of the Gullah-speaking weavers of South Carolina.

The section “Landscape and Place” includes paintings by such nineteenth-century masters as Robert S. Duncanson and Edward Mitchell Bannister, and the stark 1935 winter scene Country Doctor (Night Call) by the self-taught Horace Pippin. Sections on “Men” and “Women” examine how African-American artists have represented the black presence through portraits and studies of the nude body, as well as examinations of stereotypes. Robert Colescott’s Marching to a Different Drummer (1989) arrests the eye with its color and apparent humor, until you notice that the flashily dressed black man smoking a pipe and attempting to read a book amidst the uproar of frolicking nudes and white hands beating a trap drum, is shackled to a ball and chain. “Dance, Music and Song” includes two particularly unforgettable works: Charles Wilbert White’s Clarinetist (about 1959), an empathetic charcoal and gouache study of an unnamed musician seated with his instrument, and sculptor James Richmond Barthé’s exquisitely sensual nude bronze portrait of the Senegalese cabaret dancer known as Feral Benga (1935).

Repeatedly, the themes of “Family and Community,” “Street Life,” “Masks and Symbols,” “Spirituality,” even “Abstraction,” highlight works of fantasy, sorrow, triumph, and rage. In sum, this volume presents a singularly vivid, cogent selection of painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, and decorative art that, while revealing the richness of African-American creativity, needs no racial modifier to be hailed purely as American art.

The Tudor Home by Kevin D. Murphy with photography by Paul Rocheleau (Rizzoli). 272 pp. color and b/w illus.

The titular “Home” is the clue that this handsome volume is not about domestic architecture in Shake speare’s England, for that study would doubtless have been called “The Tudor House.” On the contrary, this lavishly illustrated book is about American houses built and decorated in one of the most appealing of all historical revival styles. Characterized by emphatic half-timbering with intervening spaces covered in stucco, deliberate asymmetrical massings of steep multiple gables, massed ornamental chimney stacks, and bays and oriels of mullioned casement windows, often with leaded glass, the Tudor revival flourished in the United States from the closing decades of the nineteenth century through the 1930s. It was inspired by antecedents rooted in late Victorian England, which themselves were influenced by the picturesque medievalism that was one facet of the aesthetic movement, and by the work of such writers as William Morris and Charles Locke Eastlake, and the designs of architects like Richard Norman Shaw.

Like most nineteenth-century revivals—rococo, Renaissance, Egyptian—the Tudor revival adopted a romantic view of history by selecting the most attractive characteristics of historical design and adding modern conveniences. Whether the Tudor style was applied to a mansion set on landscaped acreage or to a set of suburban houses on a tree-lined street, it was usually handsome and well constructed. Their distinctive visual appeal has stood up admirably to the test of time, and Tudor revival houses, many of them now a century old or more, still please the eye wherever they are preserved.

This book reveals some of the best and most appealing Tudor revival houses around the United States. Following an introduction summarizing the style and its history in America, the ensuing chapters focus on specific locales boasting noteworthy Tudor style houses or groups of houses in wealthy Hudson valley suburbs like Tuxedo Park and Bronxville, in the Main Line and Chestnut Hill suburbs of Philadelphia, and in Shaker Heights, Ohio; other examples include Virginia House, outside Richmond, Virginia, where architect Henry Grant Morse incorporated remnants of the twelfth-century Warwick Priory into his 1925 architectural scheme, and the hybrid half-timbered craftsman style Laurabelle Arms Robinson house, designed by Greene and Greene in Pasadena, California. The scale, history, and magnificence of certain houses warrant chapters of their own, including Blantyre Castle in Lenox, Massachusetts, and the Eleanor and Edsel Ford House in Grosse Pointe Shores, Michigan.

Paul Rocheleau’s beautiful photography not only documents exteriors and their landscaped settings, but interiors as well. For the most part the photographs reveal how owners of Tudor revival houses continue to follow traditional interior decorative schemes in mellow harmony with the architecture rather than trying to fight or ignore it as some now do with restored high-style Victorian interiors.

Edward S. Curtis: One Hundred Masterworks by Christopher Cardozo with contributions by A. D. Coleman et al. (Del Monico Books-Prestel in association with the Foundation for the Exhibition of Photography). 184 pp., sepia and color illus.

When Edward S. Curtis died in 1952, his brief New York Times obituary mentioned his lifelong devotion “to compiling Indian history” and that Theodore Roosevelt had written the foreword to Curtis’s monumental set The North American Indian (twenty text volumes and twenty portfolios, of which the first volume was published in 1907, the final two in 1930). As an afterthought it concluded with the bald statement that “Mr. Curtis was also widely known as a photographer.” Thus had the mighty fallen.

In fact, Curtis had been a pioneering American ethnographer, whose ten thousand wax cylinder recordings of Native American language and music, tribal lore and history represented an effort of aural preservation equivalent in significance to the contemporaneous wax cylinders of Hungarian and Balkan music and folklore recorded in the field by the Hungarian composer-ethnologists Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály. (Today a portion of Curtis’s cylinders is housed at the Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University.) Curtis was also an imaginative artist, publisher, and filmmaker; a gifted lecturer; and an early environmentalist. But photography was at the heart of his creative soul, and his position in the history of American photography should be lauded as equal to those of Alfred Steiglitz, Edward Steichen, and Rudolf Eickemeyer Jr.

Born in rural Wisconsin in 1868, the son of a disabled Civil War veteran who lived hand-to-mouth as an itinerant preacher, Curtis spent an impoverished boyhood in rural Minnesota, where he developed a love of outdoor life while accompanying his father on his pastoral rounds. Having built his first camera around age twelve, Curtis spent his teen years experimenting with photography. At seventeen he was briefly apprenticed to a photographer in St. Paul. A subsequent move to the Puget Sound area for his father’s health sparked his interest in American Indian life while enabling him to hone his photographic technique. After a stressful period following his father’s death, Curtis pursued his entrepreneurial instincts, entering into an increasingly profitable series of photographic businesses in Seattle. By 1898 he had achieved considerable recognition as a portrait photographer as well as a photographer of artistic landscapes and Native American imagery.

Like the painters Frederic Remington and Charles Marion Russell, Curtis was aiming to record imagery of an American West that was not just simply vanishing, but being deliberately obliterated by government policies. As author Christopher Cardozo notes, “It was within this hostile context that Curtis embarked on his mission to understand and preserve Native American Culture and to convince a nation that its perspectives and policies were misplaced and often inhumane.”

Of the one hundred works in this book, Cardozo observes that “Curtis’s most iconic photographs are best viewed as consciously created works of art, not merely as ethnographic documentation.” And though some of the images here are documentary, many, especially the outright portraits, ravish the eye. Of these one of the most painterly is Tâpâ, “Antelope Water”—Taos, 1905, in which the subject’s noble face, with eyes gazing away from the viewer, emerges from a white cowl. The subtleties of the draping fabric, the textures of hair and facial skin modeled by soft light and shadow are exquisite. But it is the soft highlight along the inner edge of the sitter’s upper lip that places this composition in the realm of visual poetry.

by Barrymore Laurence Scherer