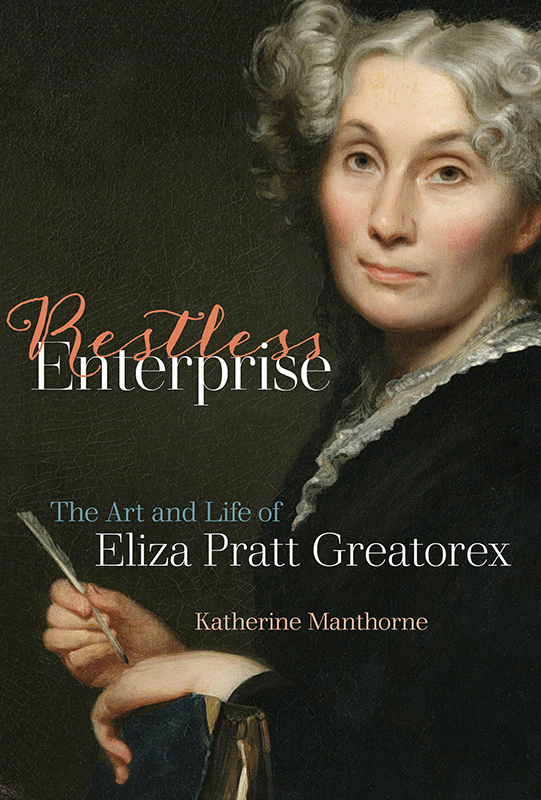

Art historian Katherine E. Manthorne has written a welcome addition to recent studies devoted to American women artists and cultural figures of the past two centuries. The flurry of such publications is especially noteworthy as we celebrate the hundredth anniversary of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, earning women the right to vote after a long struggle.

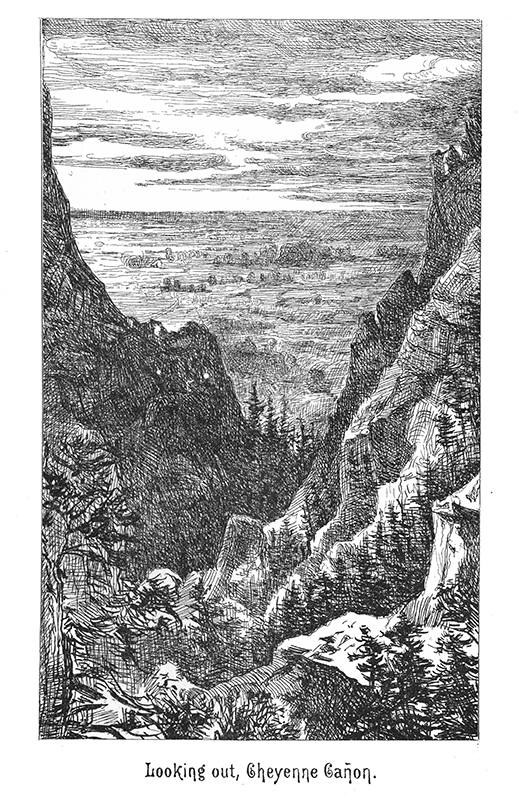

Little remembered today, Eliza Pratt Greatorex was once hailed as one of the most notable women artists in the United States. A rare female member of the National Academy of Design, she participated in the founding of art colonies in Cragsmoor, New York, and Colorado Springs, and was the first East Coast female artist to spend a summer in the Rocky Mountains. In later life, she distinguished herself as one of the leading figures in the American etching revival. Yet Manthorne, professor of modern art of the Americas at the Graduate Center, City University of New York, who began her arduous pursuit of the facts of the life and work of this distinguished artist decades ago, likens her effort to “chasing shadows.”

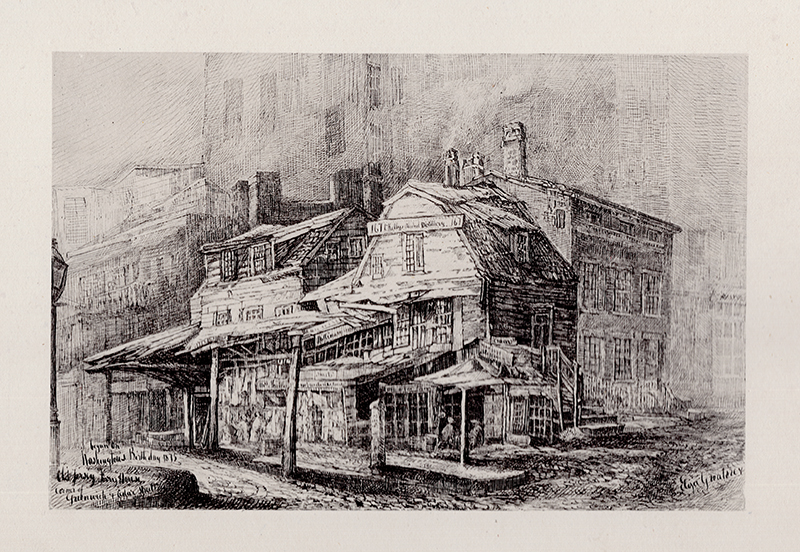

Greatorex created numerous landscape paintings— twenty-five have been identified out of approximately one hundred titles found in period records—published three books featuring reproductions of her pen-and-ink drawings, as well as several print portfolios, and a series of original drawings. But her greatest triumph was the publication of Old New York, from the Battery to Bloomingdale, a compendium of her portraits of aged buildings in the city. Almost all of these structures were demolished during the late 1860s and early 1870s to make way for new construction as the development of New York pushed relentlessly northward. Published by G. P. Putnam’s Sons in 1875 and paid for with Greatorex’s own funds, Old New York was the culmination of a decade of sketching the city’s architecture slated for destruction. The book features an array of building types and their surroundings, among them farmhouses, cottages, country seats, mansions, estates, homesteads, and ferry houses. Manthorne notes that Hippolyte Bayard’s photographs of Paris and the Parisian etchings of Adolphe Martial Potément and Alfred Delauney were precedents for Greatorex’s efforts. These French works were created around the time Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann commenced the capital’s monumental architectural renovation in the reign of Napoleon III.

The story of Greatorex’s life and art unfolds in nine chapters, beginning with her early life in her native Ireland. Manthorne follows her to New York in 1848 and tracks the artist through the antebellum era, to the Civil War, Reconstruction, and the Gilded Age.

Born on Christmas Day 1819 in Manorhamilton, a tiny village in County Leitrim in northwest Ireland, Eliza Pratt lived her childhood amid bucolic hills and vales. Yet it was not a settled life. Her father was an itinerant Methodist minister, and, as Manthorne writes, “mobility and impermanence became the defining conditions of [the family’s] existence.” In adult life, the artist emulated the peripatetic ways of her father.

Manthorne’s interest in Greatorex was enhanced by her own Irish heritage. She dedicates her book to several female ancestors of her own and her husband, James McElhinney, and to “all the brave Irish women who crossed the sea to make a home in America.” For Eliza Pratt left for America in 1848, bound for New York City as one of the multitudes who fled the Great Famine. A brother had gone to America a few years before, and her father and sister would soon join her in New York.

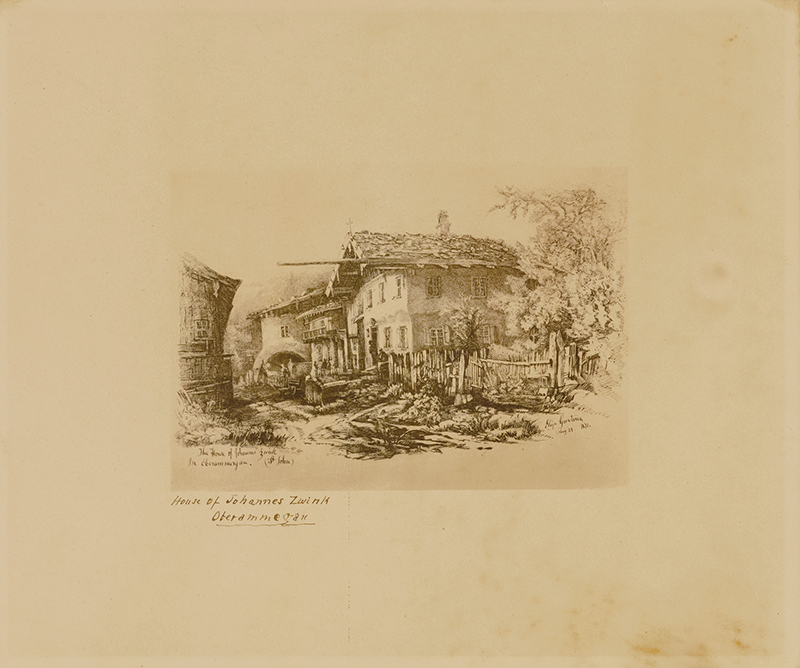

Shortly after the artist arrived in the city, she met and married British-born organist and composer Henry Greatorex. In 1859 her husband died of yellow fever in Charleston, South Carolina, leaving Eliza a widow with four children and no steady income. In the coming decades she continually juggled the demands of single motherhood and an artistic career. Occasionally, she left her children in the care of her sister and traveled alone to Europe. On most of her journeys, however, she traveled with daughters Kathleen and Eleanor, venturing across Europe, the American West, and North Africa. The daughters went on to successful careers as painters, their lives and accomplishments discussed in the epilogue to the book.

Wishing to expand on her skills in drawing and with watercolor, Greatorex studied landscape painting in New York with the Hudson River school artist William Hart. Soon, she was creating romantic landscapes in America as well as abroad. These are suffused with a brushy, hazy atmospheric treatment of sky and clouds as she aimed to create works that looked like “real places.” Thus, her early paintings have one foot in the Hudson River school and the other in the Barbizon school of France. They share kinship with the poetic and moody landscapes of her American contemporaries Jervis McEntee and Homer Dodge Martin.

In later years, Greatorex would continue her studies abroad with the painters Karl von Piloty in Munich, and painter Émile Charles Lambinet and printmakers Charles Henri Toussaint and Maxine Lalanne in Paris.

Clearly, Greatorex was always seeking to improve her own talents as an artist, but she also worked to further the cause of women’s art in America. Manthorne brings to light Greatorex’s successful effort to include fine art in the Women’s Pavilion at the Centennial Exposition held in Philadelphia in 1876. As part of this endeavor, she called New York women artists to action, urging them to submit work to ensure a presence at the fair. As for her own art, the exposition featured a comprehensive suite of her work, including Hudson River landscapes, studies she made in Bavaria, pen-and-ink drawings created in Colorado, and original drawings that were reproduced in Old New York. Greatorex also aided the cause of American women artists during her stay in Munich in the early 1870s, when she acted as an ambassador for the New York–based Ladies Art Association, investigating the possibilities for women’s art training in the German city.

Among the most engrossing passages of Restless Enterprise are Manthorne’s discussions of the lives and activities of prominent women with whom Greatorex was closely associated. Her circle included the founding editor of Harper’s Bazaar, Mary Louise Booth; the art writers Anna Howitt (author of An Art Student in Munich) and Elizabeth Fries Lummus Ellet (author of Women Artists in All Ages and Countries); the Milwaukee art collector Martha Reed Mitchell; the journalist Grace Greenwood; and the New York painter Julia Hart Beers, sister of her former teacher, William Hart.

Manthorne’s writing is especially spirited in her descriptions of Greatorex’s ambitious project of picturing the buildings of old New York in the moments prior to their obliteration. Manthorne calls out critics of the artist’s day for not digging deeper and looking closely “at Greatorex’s insistence on the theme of home in biographical and even psychological terms. Not only was she an Irish immigrant seeking a new home in a new land, but she was also the daughter of an itinerant Methodist minister who continually moved his family from one location in the west of Ireland to another, never remaining in one place for more than a year.” Manthorne argues that the artist’s ever-present “feeling of being between the land of her birth and her adopted homeland” led to her art being “redolent with loss and memory,” which extended “from her early Irish landscape paintings to her major records of the historic landmarks of New York.”

Katherine Manthorne’s splendid biography draws us into Eliza Pratt Greatorex’s restless but fruitful life of trekking back and forth across the American continent and the Atlantic in her courageous quest to both survive and thrive as a woman of creative talent, ideas, and character, and one acutely attuned to the nature of change and changing times.