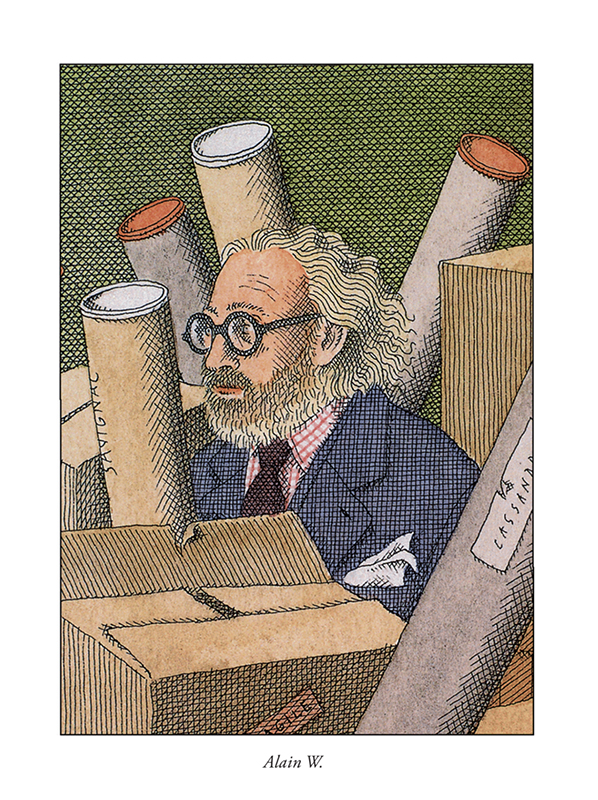

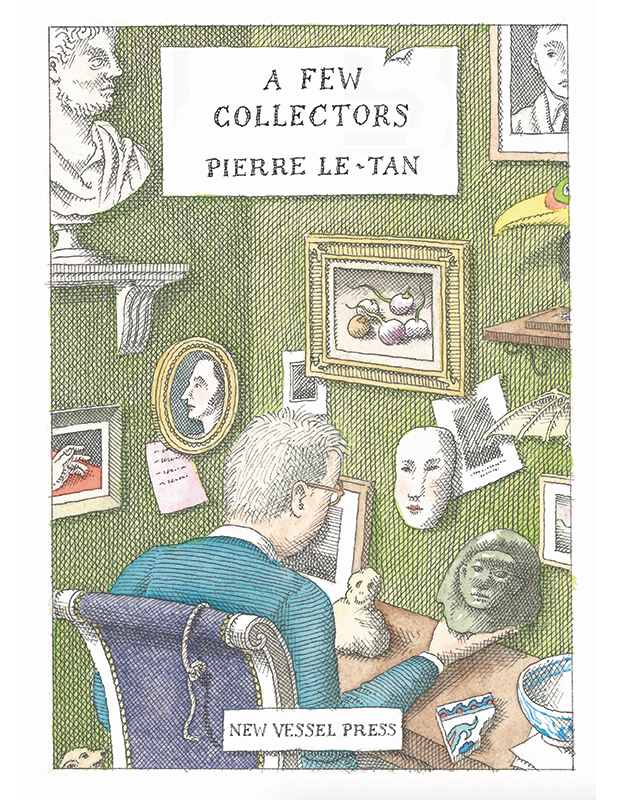

The late French illustrator Pierre Le-Tan will be familiar to a good number of you from the many covers he drew for the New Yorker and other magazines—quietly elegant works, marked by the distinctive, painstaking freehand crosshatching Le-Tan used to give his compositions depth and contours. Beyond his graphic skills, in his native Paris, Le-Tan—his father was a Vietnamese artist, his mother a French journalist—was known for his belles lettres and as a collector and man-about-town of impeccable taste, usually to be found in a museum, art and antiques galleries, or an auction salesroom.

It was in such places that Le-Tan met many of the characters he introduces us to in A Few Collectors, a slender memoir that first appeared in France six years before Le-Tan’s death in 2019 and has become available in an English translation only this year. The book consists of short, impressionistic chapters about fellow collectors Le-Tan encountered among the cultured in such locations as Paris, Rome, and Tangiers.

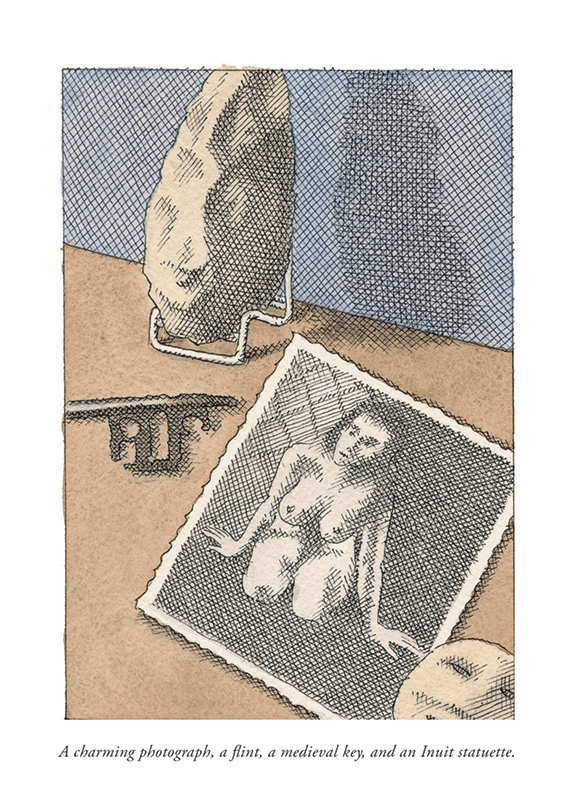

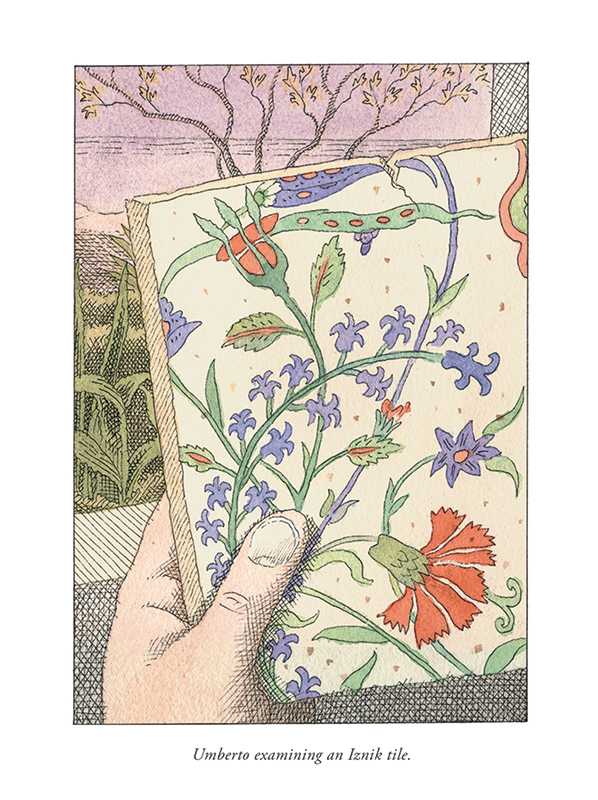

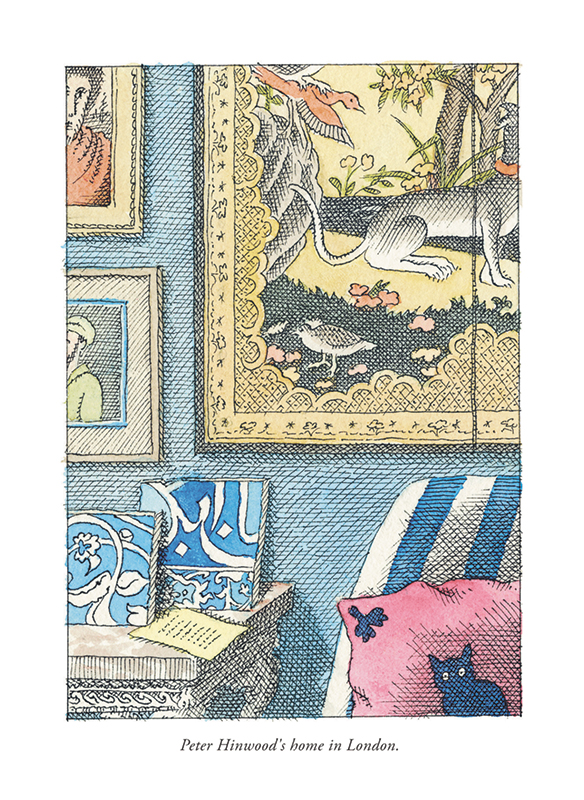

What they collect is secondary. Le-Tan makes it clear from the outset that he won’t be writing about “great collections that are of almost no interest to me, such as that of Yves Saint Laurent and Pierre Bergé.” The collections he does describe might be composed of the exquisite: Islamic tiles, Chinese porcelain, Murano glass figurines, Old Master drawings, portraits by Christian Bérard. Or of the strange and eccentric: a collection of nineteenth-century wax heads, modeled on those of Italian criminals; a collection of found, crumpled pieces of paper—restaurant checks, envelopes, and the like—set on shelves and carefully labeled with the date and place of their discovery.

Le-Tan’s true interest is in the collectors themselves, and the instincts that moved them to collect. These collectors range from an impoverished aristocrat and a minor film star to a fashion world magnifico, a New York real estate tycoon, a museum curator, and Boris Kochno, the Russian poet and the librettist for Serge Diaghilev. (Note that Le-Tan is a shameless name- dropper—as attested to by the dense, five-page index that follows a main text that runs to only one hundred pages.) Disparate as these people are, what they have in common is that each has a unique, individual sense of taste, joined to a need—even a compulsion—to express that sensibility through collecting.

Le-Tan’s illustrations are, of course, a chief attraction of the book, and their subtle sophistication is matched by Le-Tan’s writing style. He is nuanced, unafraid of ambiguity, indifferent to narrative closure. Le-Tan is also smart—he describes one collector who “was interested in African statues depicting settlers, little sought after, and thus inexpensive (a shrewd collector always buys outside of trends)”—and above all he is wise. “I have owned, I confess, thousands of objects,” Le-Tan writes of his own collecting history. “The idea of speculation has never crossed my mind, nor of ‘decoration.’ Collecting for me is both essential and completely useless.” In other words, the best collections are not built in hopes of prestige or future profit. They are, instead, an expression of, and extension of, personal character. True collectors are true to themselves.