costumes designed by Gerald Scarfe. Photograph by Karen Almond, Dallas Opera, Texas.

The Meadows Museum at Southern Methodist University in Dallas has a great collection of art from the Hispanic world. It’s a creative, entrepreneurial place. Down the road, the Dallas Opera is offering Don Carlo, Giuseppe Verdi’s grand Spanish opera, starting on March 20. Shouldn’t the two cultural institutions work together? Well, they are.

The Meadows and the Dallas Opera—joined by Madrid’s opera company, the Teatro Real—have just launched a multiyear collaboration, swapping art, singers, and marketing ploys. It’s the first international cooperative venture of its kind.

You would think that opera companies and museums would team up and pool resources quite often. Opera is about music, but also spectacle. Art and music are a natural mix, something that Stephen Sondheim figured out in Sunday in the Park with George nearly forty years ago.

The Meadows will license its art to Dallas Opera for its stage sets, and Don Carlo is a great place to start. The Meadows is hosting Alonso Berruguete: First Sculptor of Renaissance Spain this spring. Berruguete was the court artist for Charles V, the king of Spain, Holy Roman Emperor, and the father of Philip II (who launched the Spanish Armada). Carlo was Philip II’s eldest son and heir. The Dallas Opera will make images of Berruguete’s artworks—and other things from the Meadows—a core component of its set design.

In Don Carlo, the Philip II character gets involved in a love triangle between his new wife—a princess of France—and his son, Carlo. To the king, Carlo is nothing but a lovestruck nuisance who makes

seditious deals with the Flemish, whose land is then

under Spanish rule. The Grand Inquisitor makes an occasional appearance, as does the ghost of Charles V, who (spoiler alert!) ultimately drags Carlo into his tomb.

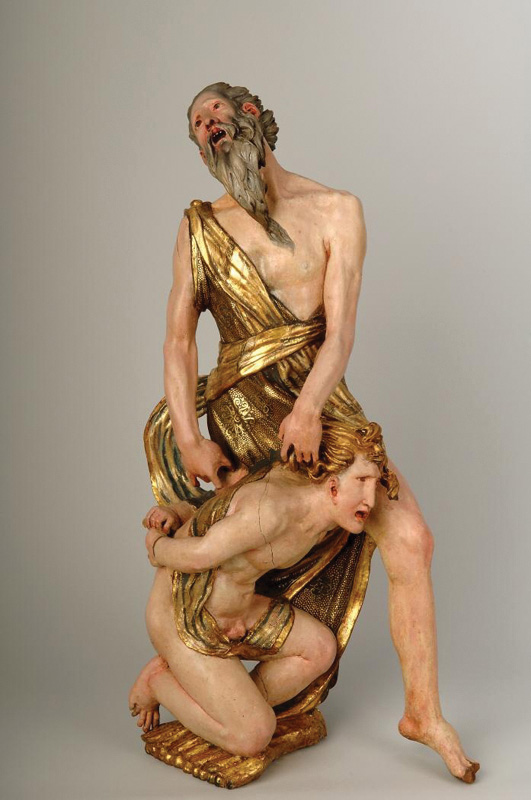

One of Berruguete’s masterpieces, likely sculpted in the late 1520s, is The Sacrifice of Isaac—a depiction of what you might call the ultimate scene of father/son estrangement. On orders from God, Abraham ties up his son and is preparing to sacrifice him when God calls Abraham off at the last moment. Philip II didn’t get any such memo. Images from the Meadows of other artworks of the 1400s to the 1600s depicting intense Catholicism will be projected onto backdrops to the Don Carlo sets.

This spring, the Dallas Opera will stage The Barber of Seville using art from the Meadows. The two opera companies will also do joint programming. It’s a great experiment. The Meadows and the Dallas Opera aren’t big organizations. But they share donors and audiences, and people in Dallas are rightly proud of their great cultural institutions. They are also willing to try new things. With this novel collaboration they have an initiative well worth following.