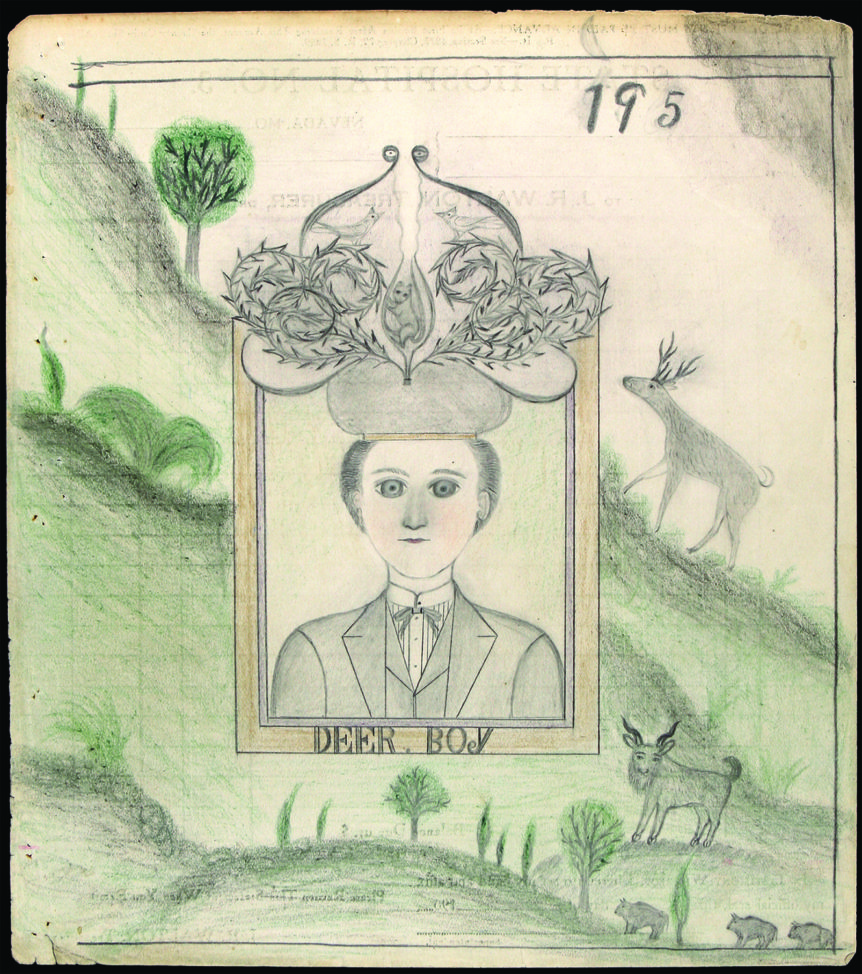

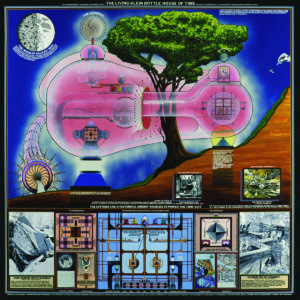

Fig. 1. DEER. BOY by James Edward Deeds Jr. (1908–1987), c. 1936–1969. Pencil and crayon on ledger paper, 9 1/4 by 8 3/8 inches. Collection of Frank Tosto; photograph by Adam Reich, courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

In Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narrative, philosopher and linguist Roland Barthes refers to the infinite ocean of human narratives.1 Into this sea of stories, we must add those of visionary artists and art brut creators who conjured their narratives outside the more predictable circuits of communication. The current exhibition Vestiges & Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic at the American Folk Art Museum provides a close look at self-taught artists through the idiosyncratic structure of their intricate and nonlinear narratives.2 The work of seminal artists—such as Henry Darger, Achilles G. Rizzoli, and Adolf Wölfli—is examined alongside that of lesser-known artists and some still practicing today. The exhibition focuses on the artists’ writing practices and the mechanisms behind their visual storytelling.

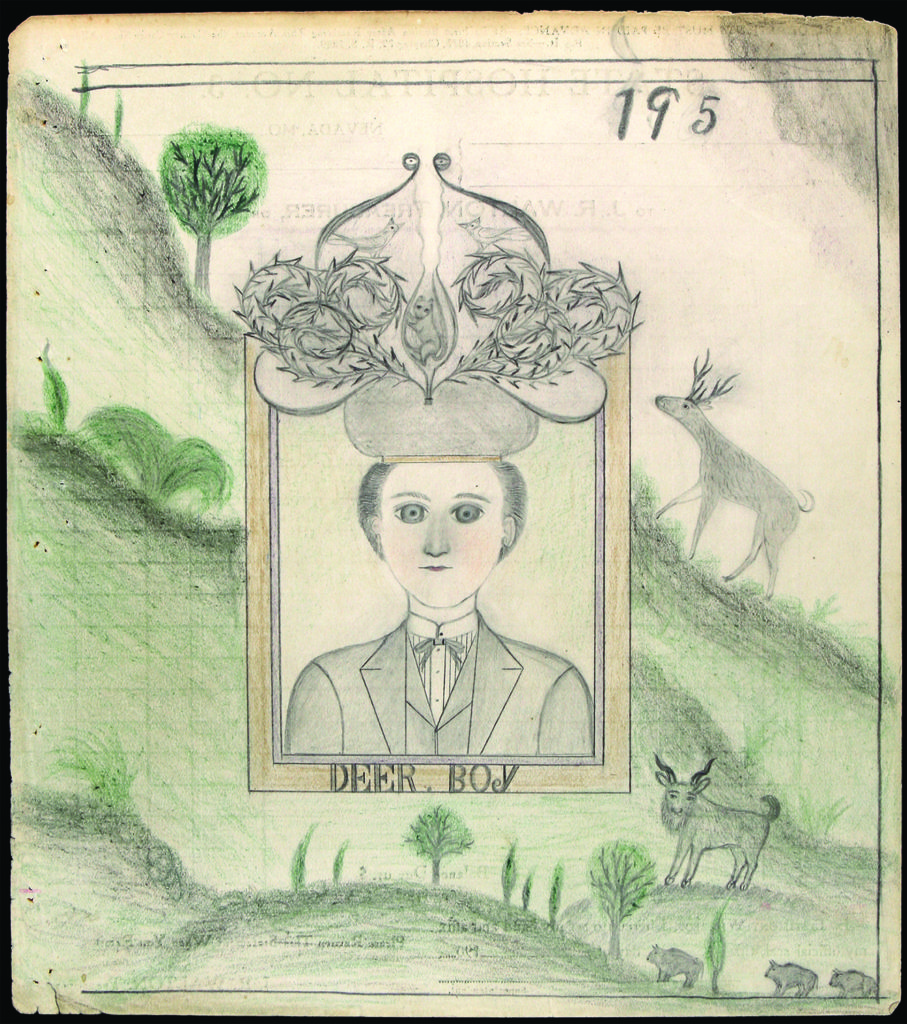

Fig. 2. Twenty panels comprising a section of Jerry’s Map by Jerry Gretzinger (1942– ), 1963–ongoing. Felt pen, colored pencil, acrylic, tape, and plastic clippings collaged on light cardboard, each panel 10 by 8 inches, totaling 40 inches square. Collection of the artist; © Jerry Gretzinger; photograph by Jerry Gretzinger.

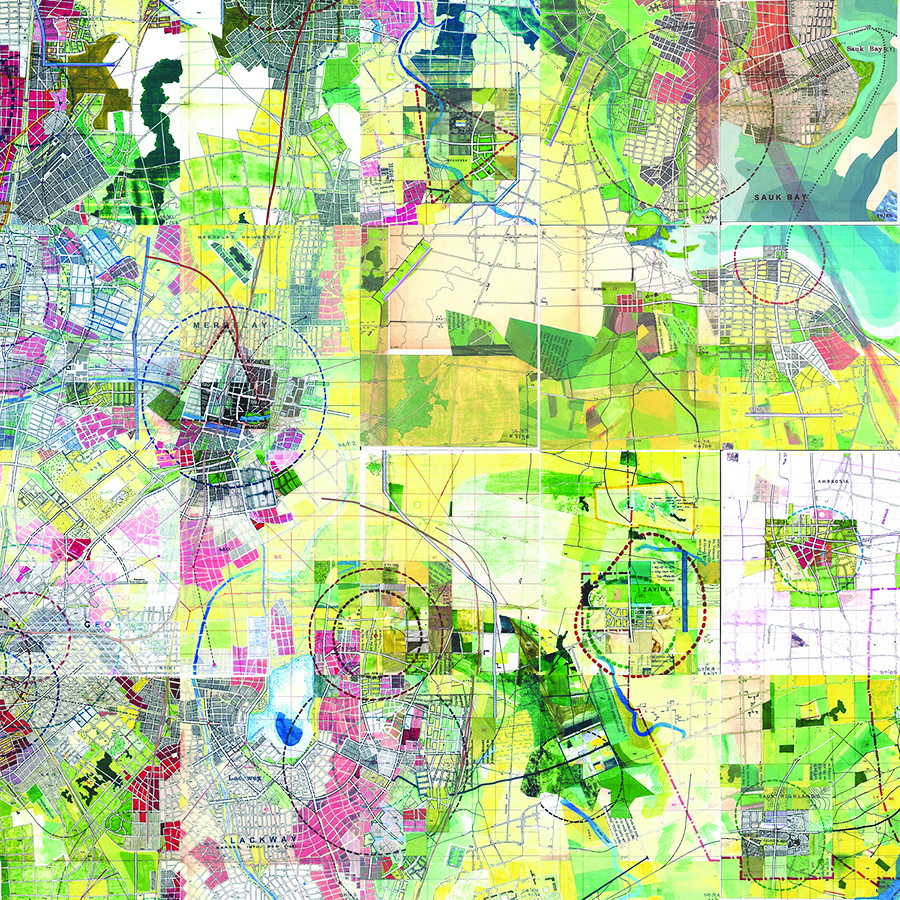

Fig. 3. The Living Klein Bottle House of Time by Paul Laffoley (1935–2015), 1978. Oil, acrylic, and vinyl lettering on canvas, 73 1/2 inches square. Collection of Norman and Eve Dolph,© Estate of Paul Laffoley; photograph courtesy of the Estate of Paul Laffoley and Kent Fine Art.

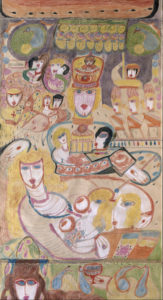

The exhibition presents manuscripts, illustrated diaries, evolving imaginary maps, drawings conceived in series, multipart collages, and journals filled with coded language. In each case, the images and the written elements become an inseparable device. Among them are three rare notebooks filled with drawings by Aloïse Corbaz, a canonical art brut figure who spent most of her life in the psychiatric hospital of La Rosière, in Gimel-sur-Morges, Switzerland.3 Created between 1938 and 1963, these cahiers are paired with her largest and arguably most ambitious piece, the Cloisonné de théâtre (Theatrical Partition) of 1950–1951. This masterpiece (Figs. 4, 4a, 4b), made on a forty-six-foot-long scroll, hand-stitched from fragments of paper, was conceived as a theatrical play depicting Corbaz’s dramatic love story.4 In this complex visual narrative, scenes are stacked one underneath the other and unfold vertically. The drama is divided into three acts, each framed by visual interludes and comprising two scenes. The first act, dominated by vivid colors, represents two couples. Above are depictions of Napoléon I—a recurring character throughout Corbaz’s oeuvre—and his wife, Joséphine. Below them are a man and woman with red hair who appear to be dancing. Act I evokes a joyful moment in the artist’s life, when she fell in love with a theology student, and when she subsequently served as a governess at the court of the German emperor Wilhelm II, for whom she developed an amorous passion and a fictitious intimate relationship. Act II conjures up the romantic disappointments of the artist, and Act III presents the deceptions of the flesh. Partitioned from the rest of the composition by the river Styx, the conclusion, according to the artist, depicts Eros and Psyche leaving Earth to become immortal.

Fig. 4a. Detail of Cloisonné de théâtre (Theatrical Partition) by Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964), 1950–1951. Collection of Christine and Jean-David Mermod, Lausanne, © Association Aloïse; photograph by Philip Bernard.

Fig. 4. Detail of Cloisonné de théâtre (Theatrical Partition) by Aloïse Corbaz (1886–1964), 1950–1951. Colored pencil and geranium sap on ten sheets of paper sewn together, 3 feet 3 inches by 46 feet 3/4 inch. Collection of Christine and Jean-David Mermod, Lausanne, © Association Aloïse; photograph by Philip Bernard.

Among other works combining writing and imagery are the fourteen volumes (seven bound, seven unbound) of Darger’s literary magnum opus, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is Known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion, created between 1910 and 1939; this 15,145-page novel is displayed alongside Darger’s large-scale double-sided watercolors. Presented as well is a selection of drawings taken from the twenty-five thousand pages of Adolf Wölfli’s grande oeuvre, which is divided into forty-five large notebooks. Following the developing studies on brut literature, notably those initiated by art historian Michel Thévoz, Vestiges & Verse investigates the sequential, interconnected, and developing aspects of these works as an essential step in capturing their articulation and scope.5 Each of the selected sequences in the exhibition stands as a “vestige,” or remnant, embedded in a larger, more ambitious project. These constituent units map out the work more globally and shed light on connections that may be otherwise obscured.

Fig. 5. La Blanche Cavale by Corbaz, c. 1942. Colored pencil and pencil on paper, in a blue cardboard cover notebook (20 pages, bound), 9 5/8 by 13 inches. Collection abcd / Bruno Decharme, © Association Aloïse; photograph courtesy of abcd.

Fig. 6. Two pages from Brevario Grimani by Corbaz, c. 1943. Colored pencil and pencil on paper, in a notebook (19 pages, bound) 9 5/8 by 13 inches. Collection abcd / Bruno Decharme, © Association Aloïse; photograph courtesy of abcd.

One common motif and visual mantra in the artists’ projects is the creation of inventories—including highly descriptive recordings of factual events, the scrutinizing of recurring characters, and the extensive collection of intellectual paths leading to a particular knowledge. Art historian Jo Farb Hernandez mentions that Achilles Rizzoli “was a prodigious accumulator, with books, lists, newspapers, letters, and other documents found among his effects.”6 Henry Darger lived similarly in his overcrowded one-room apartment. John MacGregor notes that Darger’s prose is made of repetitions of rhythmic words, various neologisms, overwrought descriptions, and obsessive details.7 He writes that Darger’s accounts of battles can stretch over hundreds of pages, and the conflicts can be carried out simultaneously on many fronts in several countries—remarking that the artist “often betrays a loss of control, as if the writer’s approach was dominated by free associations and complex visual fantasies.” “His style,” MacGregor continues, “is sometimes similar to that of a war correspondent who broadcasts recorded bulletins at night on the secbattlefield.”8 The fictional world of artist Jerry Gretzinger is made up of thousands of panels; the refined “thought-forms”9 written by Paul Laffoley elucidate symbols and content in his paintings; and the illustrated travel adventures exhaustingly developed by Wölfli,10 are examples of nonlinear projects, regularly imprinted by the artist’s repeated attempts to summarize the wanderings of his mind.

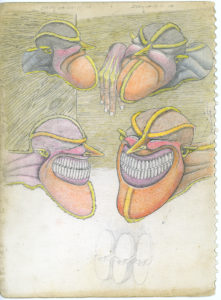

Fig. 7b. Page from Frankenstein Sequel (aka Protége) by William A. Hall (1943–), 2011–ongoing. Dated and numbered “SAT–08•06•11 14” at upper left, “SUN– 08•07•11 14” at upper right, “MON–08•08•11/ SUN–14” at center right, “MON–08•08•11 <—13 15” at center left. Pencil on paper, 10 by 12 1/2 inches. Collection of the artist, © William A. Hall; American Folk Art Museum photographs.

Fig. 7a. Page from Frankenstein Sequel (aka Protége) by William A. Hall (1943–), 2011–ongoing. Dated and numbered “WED 07•27•11 28, 29, 30 & 08•01” at upper left, “XI” at upper center, inscribed “ARTHUR FRONT” at lower left. Pencil on paper, 10 by 12 1/2 inches. Collection of the artist, © William A. Hall; American Folk Art Museum photographs.

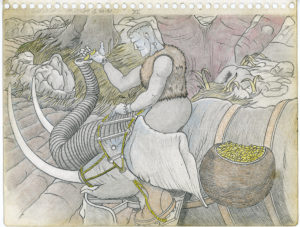

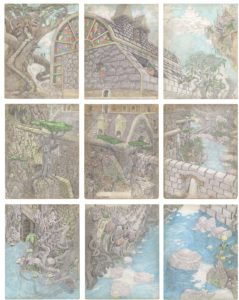

A particular capturing of data can be seen in the practice of William A. Hall, a formerly homeless visionary artist who for a time lived in his car. On the backs of his drawings he records such details of daily life as a definition that he just read in the dictionary; a short discussion that he had with a police officer; or his reaction to a sudden horn blast nearby. These notes containing precise dates and times, which are not visible if the work is traditionally framed, stand as time markers: interruptions in his intensive working flow coming from the outside, and recalling his ever-changing parking locations from one Los Angeles neighborhood to another, as well as recordings of thoughts worthy of note occurring simultaneously with his drawing activity. Aside from pursuing the writing of a novel titled Protége since 2011, Hall is mainly known for his highly detailed graphite and colored-pencil drawings, theaters for the sublime, with an atmosphere of hyperrealistic futuristic illustrations. Finely executed cars and trains transcend their original function, becoming all-powerful engines, reinforced with curvilinear shockproof armatures and safety features, which he began to design in 1984, after his niece was killed in a traffic accident. His vehicles are transplanted into the hearts of post-apocalyptic, unpopulated scenes and out-of-time Lilliputian landscapes that are inhabited by giant twisted trees, waterfalls, rocks, and wood machines of his own invention.

Fig. 8. Untitled by Hall, 2015. Signed and dated “WA HALL/ 2015” at lower right. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, each page 11 by 14 inches (three-page composition). Collection of Stephen Holman and Josephine T. Huang; © William A. Hall; Reich photograph, courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum.

Fig. 9. Pumpkinwall Castle by Hall, 2013. Pencil and colored pencil on paper, each page 14 by 11 inches (nine-page composition). KAWS, © William A. Hall; photograph courtesy of the Henry Boxer Gallery, Richmond, United Kingdom.

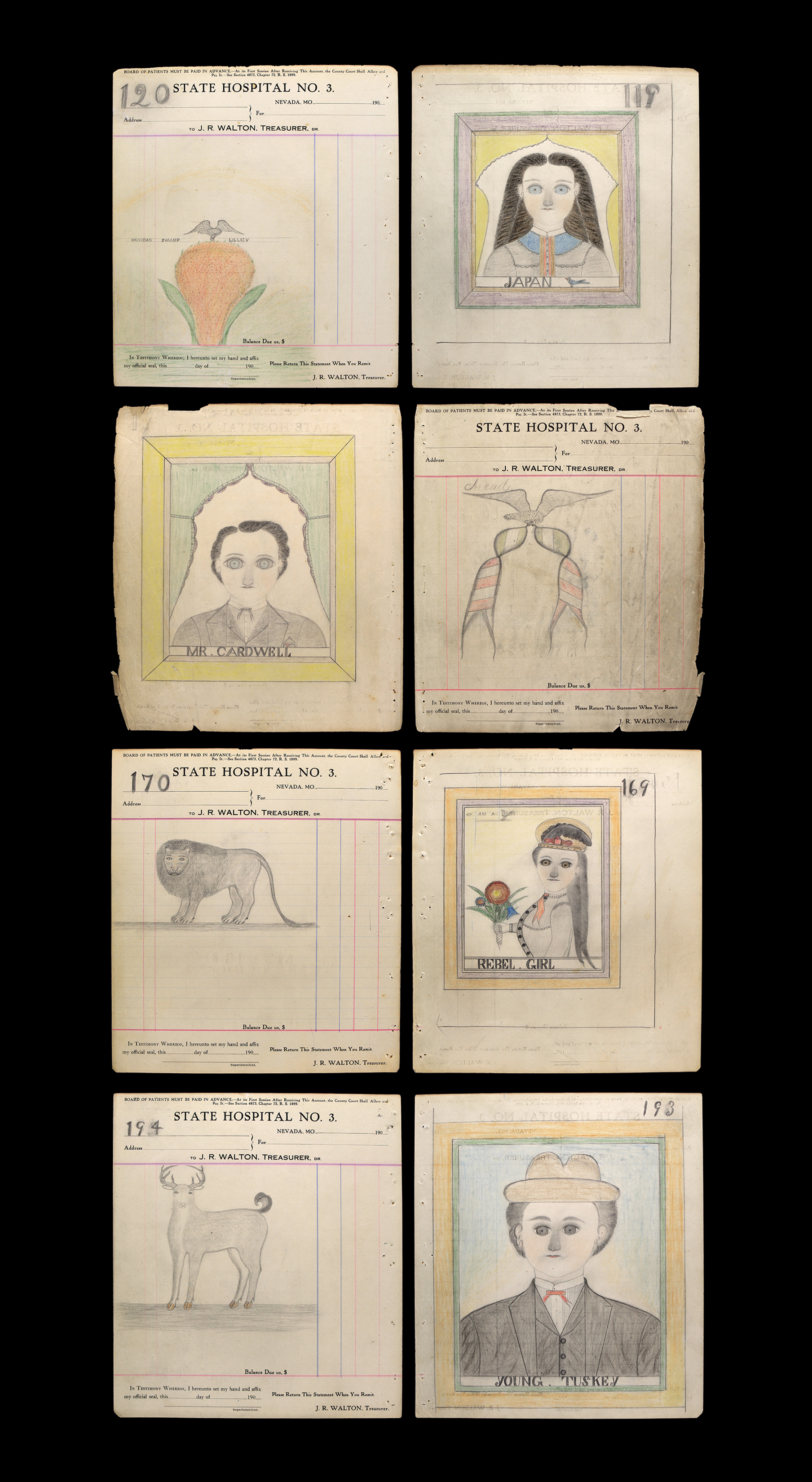

The oeuvre of American James Edward Deeds Jr., with his gallery of characters and their enigmatic associated imagery—developed on both sides of sequentially numbered pages he bound in an album—allows us to approach the inventory in terms of cumulative memories. As Allison C. Meier observed: “The first image in the album of 283 drawings … is an eagle lifting a banner. The bird is strikingly similar to a sculpture over the entrance to State Hospital No. 3, in Nevada, Missouri. Deeds entered its walls in 1936, and there spent the next thirty-seven years. Aside from this page, his art rarely refers to the mental institution. Instead, fantastic visions of steamboats, horse-drawn carts, and circus trains recall an earlier era.”11 Meier mentions the hypnotic rhythm of such portraits as REBEL GIRL or DEER. BOY (with foliage-formed antlers on his head), with their gaping eyes and carefully executed hairstyles and hats topped with feathers. “The broad faces,” she writes, “pass like people glimpsed in train windows, and they become otherworldly as the pages continue.” If Deeds’s pairings of people with objects or animals might seem deliberate, Meier continues, “these figures have no obvious connection to the object pages. Some sections go back and forth between showing landscapes and animals, but overwhelmingly every non-person drawing is followed by a portrait.… Deeds must have had some books, images, or other sources for his subjects, but the consistency of idyllic style makes them now obscure. Likewise, some of the labels like ‘AUSTRALIA GIRL’ and a small map of ‘A PORTION ON SOUTH. AMERICA’ allow us to place an atlas in his hands, through which he envisioned distant places. Yet the banjos, bison, and ‘BOOL FROGS’ give it all an American twang.”12

Fig. 10. Another page from Frankenstein Sequel (aka Protége) by Hall, 2011–ongoing. Pencil on paper, 12 1/2 by 10 inches. Collection of the artist; American Folk Art Museum photograph.

Reflecting on his own oeuvre, artist Achilles Rizzoli admitted that “an opus of this nature has a limited following, almost nil. The terrestrial audience may venture ridicule; on the other hand, the celestial audience simply cannot feel but otherwise.”13 The oeuvres selected for Vestiges & Verse allude to the intricate and often convoluted nature of epics, in which voices are bestowed upon elevated characters—notably, alter egos of the artists—implementing visionary systems filled with metaphysical questionings. An epic is, by definition, a long poem, typically derived from ancient oral tradition, unfolding the history of a nation and the adventures of heroic figures—the latter of whom are survivors, guardians of memory. In a digital age marked by decoding and encryption, when the very modes of communication engage different cognitive perceptions and sensibilities, we can imagine that these distinctive bodies of work—once dismissed for their illegibility, unconventional materials, and grandiosity—might be considered as newfangled models for the present day.

Figs. 11a, 11b, 12a, 12b, 13a, 13b, 14a, 14b. Each recto and verso of a single sheet, c. 1936–1969. Pencil and crayon on ledger paper, 9 1/4 by 8 3/8 inches. From top: MEXICAN SWAMP LILLEY/ JAPAN by Deeds. Collection of Hannah Rieger, Reich photographs, courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum; MR. CARDWELL / Untitled (arcade) by Deeds. Collection of Frank Tosto, Reich photographs, courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum; Untitled (lion) / REBEL GIRL by Deeds. Collection abcd / Bruno echarme, photograph courtesy of abcd; Untitled (deer) / YOUNG. TUSKEY by Deeds. Tosto collection, Reich photograph, courtesy of the American Folk Art Museum, New York.

Vestiges & Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic is on view through May 27 at the American Folk Art Museum in New York. The exhibition is accompanied by a scholarly catalogue of the same title, published by the museum.

1 Roland Barthes, “Introduction à l’analyse structurale des récits,” Communications, no. 8 (1966), pp. 1–27. 2 This exhibition is framed as a sequel to our 2015 exhibition titled When the Curtain Never Comes Down, which observed the practices of self-taught artists from the viewpoint of performance art, and thus privileged a disciplinary approach centered on mediums of expression, materiality, and public orchestration. 3 This section on Corbaz is an excerpt from Valérie Rousseau and Aurélie Bernard Wortsman, “Aloïse Corbaz. A Visual Theater,” in Vestiges & Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic, ed. Valérie Rousseau (American Folk Art Museum, New York, 2018), n.p. 4 Jacqueline Porret-Forel, Aloïse et le Théâtre de l’Univers (Skira, Geneva, 1993), p. 131. According to the author, Corbaz mainly used colored pencils combined with watercolor, as well as unconventional materials: she obtained a unique hue by rubbing geranium flowers that she picked from the hospital garden, applied on the paper with her saliva to blend the coloration. 5 Michel Thévoz, the former director of the Collection de l’Art Brut in Lausanne, Switzerland, produced extensive studies in this domain (Écrits bruts, 1985). This museum was founded after the donation by French artist Jean Dubuffet of his substantial collection of art brut in 1971, which included many examples of brut literature and works in which written elements and images are intermingled (by Jeanne Tripier, Adolf Wölfli, Carlo Zinelli, to name a few). 6 Jo Farb Hernandez, “Divine Design Delights,” in Jo Farb Hernandez, Joanne Hernandez, and Michael Beardsley, A. G. Rizzoli: Architect of Magnificent Visions (Abrams and San Diego Museum of Art, New York, 1997), p. 22. 7 John MacGregor, quoted ibid., pp. 13–14. 8 Ibid. 9 Paul Laffoley, Elizabeth Ferrer, Jeanne M. Wasilik, J. W. Mahoney, Architectonic Thought Forms: A Survey of the Art of Paul Laffoley, 1968–1999 (Austin Museum of Art, Austin, TX, 1999), p. 96. 10 Wölfli presumably used atlases, travel books, and illustrated magazines. However, the outer world data are recycled, if not instrumentalized, as quarries for the construction of his own larger project. 11 Allison C. Meier, “James Edward Deeds Jr., A Sequence of Portraits and Pastoral Scenes Rescued from a Discarded Album,” in Vestiges & Verse: Notes from the Newfangled Epic, n.p. 12 Ibid. 13 Hernandez, “Divine Design Delights,” p. 59.

VALÉRIE ROUSSEAU, curator of the exhibition Vestiges & Verse, is curator of self-taught art and art brut at the American Folk Art Museum.