As a civilization, we do not value paper very much. If China, which invented paper as we know it today, has always cherished this commodity, for most of us it is thoroughly expendable: “Not worth the paper it’s printed on” has passed into proverb. And contemporary art, which calls all hierarchies into question, falls strangely silent before the calculation that, through some natural and unalterable law, a painting on paper possesses not one-fifth or even one-tenth of the value it would have on canvas.

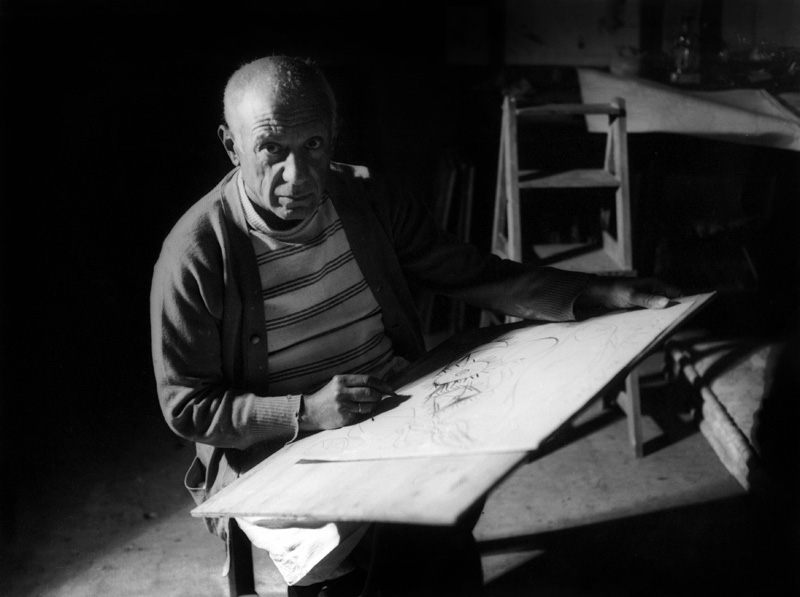

To judge from the evidence of Picasso and Paper, an exhibition mounted at the Royal Academy of Arts in London that will be coming to the Cleveland Museum of Art, however, few artists have been as alive to paper’s inherent potential as the man from Malaga. Paper was the real arena of Pablo Picasso’s action, the laboratory in which he forged the future of art. Surely he painted countless masterpieces on canvas; but the “canvasness” of canvas—even the “paintness” of painting, while we’re at it—does not seem to have bewitched him as it later would the artists of the New York school. But the moment Picasso put hand to paper, whether with pencil or pen, chalk or pastel, he seems to have experienced a surge of power such as Antaeus felt the instant his foot touched down on Mother Earth. Lest we forget, much of the cubist revolution was played out on old newsprint, which Picasso often repurposed in preference to canvas. In fact, what may be the earliest object we possess from his hand is a paper cutout depicting a dog, from 1890, when he was eight or nine years old. Curiously, the general aesthetics of that work recur in the form of a paper goat in the present show, fashioned by the nearly octogenarian Picasso seventy years later, in 1960.

As the exhibition demonstrates, there was no aspect of paper, with the possible exception of origami, that Picasso did not embrace and bend to his artistic will. He experimented with photographs and photograms, prints and etchings, collage, and, of course, pen and paper. It is especially through this last medium that his true greatness is revealed. In his opportunistic and self-aggrandizing account of his artistic evolution, Picasso once claimed, as he visited an exhibition of art made by children, “When I was their age I could draw like Raphael, but it has taken me a lifetime to learn to draw like them.” This is a wonderful paradox, even if, as regards autobiography, it is somewhat wide of the mark. But although it is an open question whether Picasso’s drawings ever really equaled those of Raphael—or, for that matter, Ingres or Degas—he was obviously a great draftsman, probably the greatest of the twentieth century. The main difference between him and them is that his probing, manic eye was forever seeking power and expressiveness in the visual world, rather than the optical truth achieved by those illustrious predecessors.

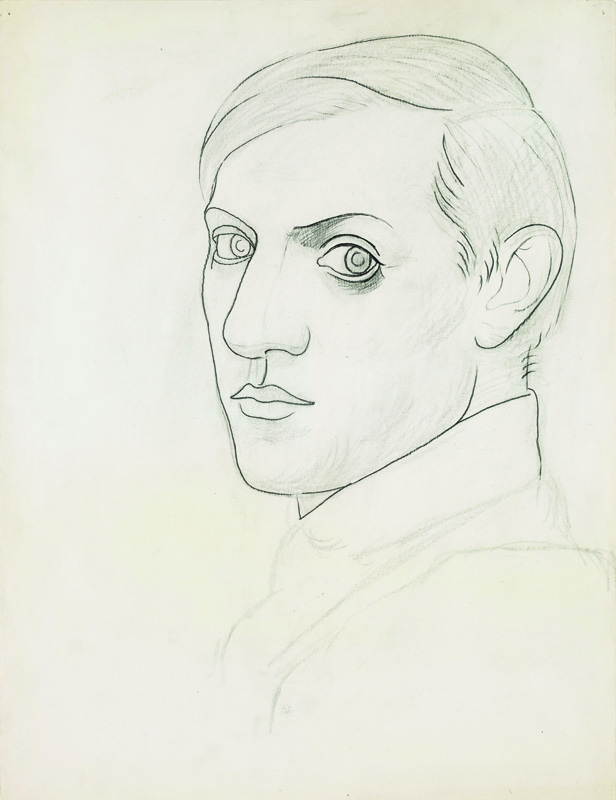

In general, Picasso was an artist of explosive passions, expressed in thickly textured paint and in squalls of spasmodic lines. The two exceptions are the tyrannical self-control of his cubist paintings, and the pure contours of the drawings he made during his involvement with the Ballets Russes. It was during that latter Apollonian interval, especially from about 1917 to 1922, that Picasso produced some of his finest works on paper. In this one period of his career, which coincides with a two-month stint in Rome, color retreats and the pure whiteness of the paper, at the critical instant of its encounter with ink or pencil markings, asserts itself in depictions of Sergei Diaghilev and Jean Cocteau, of the dealer Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, and of Picasso himself (Fig. 7). Yet even here, despite the pure Platonic contours, we sense the artist’s full and sympathetic engagement with the subjects he so ably conjures into life.

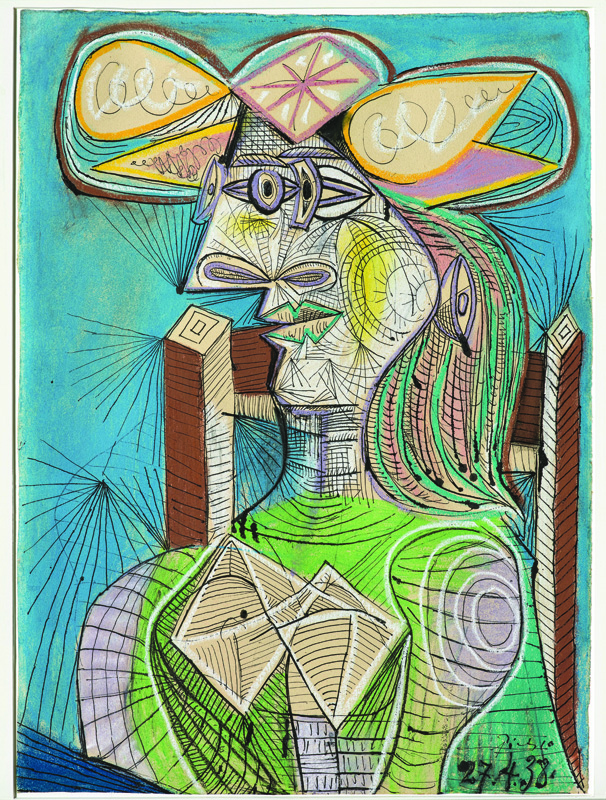

In the next stage of Picasso’s evolution, he passes from rarefied classicism to a more proletarian conception of the human form—all thick hands and weighted contours. Not the least pleasure of these newer works is the way in which the rough-ness of the paper draws out the granularity of the pastel. Similarly, once he moves into his surrealist period, the primordial forms of Sketchbook Study: Bather Opening a Beach Cabin of 1927, etched in graphite, seem to awaken the minute furrows of the paper itself.

Picasso’s involvement with photography has been relatively little studied, but it deserves more attention than it usually receives. On a return trip to Spain in 1909, he printed several deft and clear-eyed views of Horta de San Juan (or de Ebro), images in which the town itself and its clutter of medieval rooftops rise up in isolation beside Santa Barbara Mountain. Nearly thirty years later, in collaboration with his mistress at the time, Dora Maar, a photographer herself, Picasso created in the darkroom what were called photograms, images that use light as cameras do, but that make no actual use of cameras and thus do not record reality. One of the resulting images, from 1937, depicts Dora Maar in profile, while a generation later, Picasso collaborated with André Villers on several lively pictures depicting goats and fish and masks.

Such was Picasso’s affinity for paper that ultimately he leaped beyond its flattened receptivity to two-dimensional markings and landed in the realms of sculpture. In his extraordinary open-form Head of a Woman (Fig. 6), created on December 4, 1962, the folded paper cunningly expands to be-come the full-lipped profile of a beautiful woman. To this are added spare penciled lines that collect to become eyes and hair, seen frontally.

Beyond the specific and special status that paper clearly held for Picasso throughout his long life, his use of it was largely consistent with the rest of his multifarious output, reflecting as it did each twist and turn of his career. Many of the nearly three hundred works in the exhibition are every bit as rich and full as oils on canvas (some of which are included as well). Even viewers who are not interested in paper as such can hardly fail to be dazzled by the consistent force and visual intelligence of Picasso’s art, irrespective of the material base on which it occurs.

Picasso and Paper was originally scheduled to run from May 24 to August 23 at the Cleveland Museum of Art; visit clevelandart.org for updates.