Art therapy was a popular aspect of ceramics enterprises in the early part of the twentieth century. The precedent set by Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago inspired many affluent and progressive women to develop programs in art forms from weaving and embroidery to jewelry making, metalwork, and, especially, crafting ceramics. Potteries from Marblehead, Massachusetts, to the Arequipa Pottery in Fairfax, California, hailed the recuperative properties of working with clay and decorating and glazing vessels and tiles. Underprivileged immigrant children and adults, mostly women, found outlets for artistic expression and social connections in organizations such as settlement houses. Among the finest vases and tableware created as a part of this movement came from Boston’s Paul Revere Pottery and its “Saturday Evening Girls,” a group of young women who met and worked together on weekends. Though their efforts often tended toward more casual or quaint wares, there are standout objects that merit analysis as exceptional contributions to the history of American ceramics.

The Paul Revere Pottery was funded by philanthropist Helen Osborne Storrow (1864–1964) as a combination of programs previously developed at the Library House Club and North Bennett Street Industrial School. Located in the North End, this artistic enterprise provided girls from grade school to high school graduates with exposure to dance, drama, music, fine art, and literature. Social education and personal friendships developed between participants in day-to-day interactions and various performances for one another and the community. Edith Brown and Edith Guerrier (1870–1958) met through the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and organized the Revere Pottery based on a mutual commitment to the value of arts education. As partners in life and art, the two Ediths “lived together independently, outside of conventions of a male-dominated society” as constant companions until Brown’s death in 1932. Connecting traditions of rural community potteries in Europe to Boston’s immigrant populations led the women to establish the pottery in 1906 as an endeavor to help poor girls and women. This “American peasant ware” coincided with the American art pottery movement, but ceramics from the Saturday Evening Girls were distinct in many ways from the more widely known achievements of the Grueby Pottery in Boston, Newcomb Pottery in New Orleans, Gates Potteries near Chicago, and Van Briggle Pottery in Colorado Springs.

Principles of the arts and crafts movement were manifest in the Saturday Evening Girls, especially handcraftsmanship, integration of art into everyday life, and healthy working conditions. Creating and understanding art was believed to improve a person both morally and spiritually, and Boston’s cultural leaders attempted to use art education to alleviate the social effects of industrialization, mass immigration, and the resultant living and working conditions. Boston’s community of arts and crafts devotees overlapped significantly with its elite society with standing in the fine arts, a fascinating phenomenon at this social level unique among American cities. By establishing standards for taste and culture, Boston’s wealthiest residents felt they elevated themselves above the lower classes. Many held the arrogant belief that neighborhoods of immigrants—for example in the North End—were filled with simpleminded manual laborers, who should be educated, especially about the arts. Leaders at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (founded in 1870), its Museum School (1876), and the Massachusetts Normal School of Art (1873) trained artists and artisans and taught artistic discernment. Instruction in drawing was broadly disseminated in Massachusetts public schools after legislation was passed mandating that all cities with a population of ten thousand or more incorporate drafting classes.

Research has revealed that Edith Brown, the artistic director of the Saturday Evening Girls, was the designer of many of the group’s early works. Charming storybook imagery was common, a style that stemmed from her success as a professional children’s book illustrator. Many of these forms were tableware—rather than art vases—featuring roosters, bunnies, chicks, geese, and even exotic species such as camels. The cookie jar in Figure 1 is an excellent model of this type, with pairs of roosters meeting as if for conversation, alternating with elegant trios of tall leaves, all set against a pleasing horizon. The palette is limited to crisp sections of green (effectively integrated at bottom and top rim), blue, yellow and white, with careful delineations in bold black lines.

A pitcher executed by the Saturday Evening Girls’ most gifted decorator, Sara Galner, is an even more exceptional tabletop item, featuring gorgeous tulips on leafy stalks before a green landscape with a horizon and narrow sky (Fig. 2). The flowers tower against the grounds behind them, creating a studied but disorienting perspective. The brilliantly conventionalized tulip blossoms repeat in vibrant yellow at the top but the dominant leafwork fails to contrast well with the vegetation behind it.

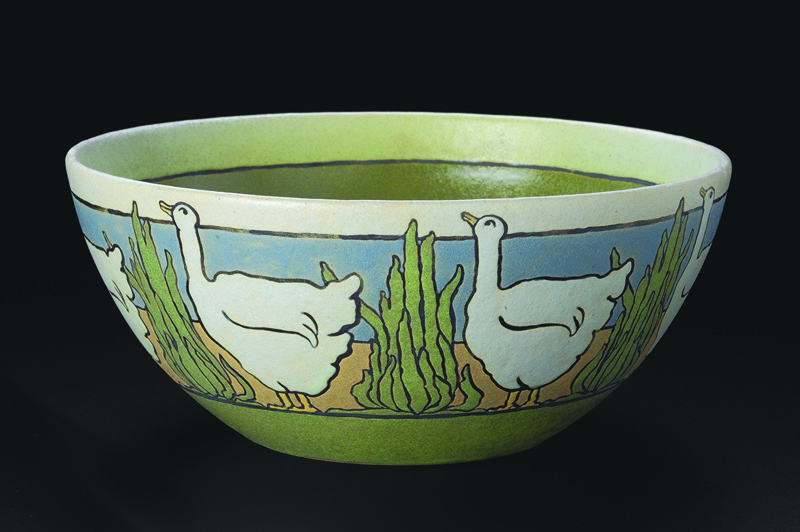

Bowls were so popular among the utilitarian wares of the Paul Revere Pottery that the retail operation was called “The Bowl Shop.” An exemplar features geese processing around the body, amid leafy bushes, ground, and sky (Fig. 3). In addition to the refined coloration and perfectly fired white glazes, the geese’s heads peeking up into the white top border is a sophisticated detail that integrates the work from top to bottom.

Even in these quaint forms, the distinctiveness of the Saturday Evening Girls’ style is apparent. Designs feature a small number of elements, often with similar conventionalized imagery and a limited range of colors. These stylized decorations in glaze were created with the cuerda seca technique, the ancient method for applying wax or a similar substance infused with manganese, producing precise and bold black outlines. The lines of manganese wax created clearly separate fields of color and, having burned off in the kiln, left dramatic black lines that establish the visual impact of the decoration and harmony of effect.

The artisanal craft and casual elegance of tableware leads directly to the charming and evocative landscape scenes created by the Saturday Evening Girls to ornament a variety of other vessels. A stylish tea caddy (Fig. 4) demonstrates the profound impact of the aesthetic theories of Arthur Wesley Dow, the classes he taught, and the books he authored, especially Composition (1899) and Theory and Practice of Teaching Art (1908). Dow understood a landscape as a “pattern of lines,” urging students to compose the tableau rather than report visual facts. His emphasis on pattern is key to understanding the Paul Revere Pottery, where decorators were keenly attentive to the essential “main lines” and “arrangement of rectangular spaces much like the gingham and other simple patterns.” These principles are brilliantly realized on an unassuming vase where trees cut silhouettes against fields of green, clusters of yellow houses, and an azure sky (Fig. 7). For Dow and for the Saturday Evening Girls, this diagrammatic approach to depicting a landscape created not merely reductive convention but also haunting arrangements suffused with emotion.

Though later works are often misunderstood, a remarkable 1922 vase demonstrates Edith Brown’s singular abilities in the arrangement of the complex sections of trees, charming countryside imagery, and a beautifully rendered lake (Fig. 6). Boldly outlined trees, rolling hills, and houses typical of Dow’s compositional technique evoke earlier vases, but the water and sky sections are naturalistic, shaded with various textures and many gradations of blue. The sunset is impressionistically dabbed with painterly streaks of white clouds and fiery pink hotspots of sunlight. Lovely tiles and trivets featured similar presentations of country houses, the marshes around Boston, and trees, lakes, and undulating hills (Figs. 5, 9).

Turning to significant floral vases, truly the artistic zenith of the Saturday Evening Girls, our analysis will commence with the finest work ever executed at the Paul Revere Pottery (Fig. 8). An astonishing modernism permeates the design, set with four similar, but not identical, chrysanthemum blossoms rendered in meticulous detail. The bushy, jagged leafwork in deep green is rendered against a lighter verdant field; the gorgeous ivory flowers stand in bold relief against a bright two-toned horizon of yellows. Vividly rendered and fastidiously controlled cuerda seca ensured precise presentation of the stylized flowers and perfect unity from bottom to top. The Paul Revere Pottery was clearly proud of this singular design, which appeared in an article about the pottery published in The House Beautiful in 1914. Remarkably, the model was offered in a Revere catalogue, where it could be ordered in this version or a combination of blue, green, and cream. The high price of $50 likely reflects the complexity of the decoration and polychromed glazes and perhaps limited orders for the form; only the illustrated example is known.

Three other floral-decorated vessels stand in a tier just below the Chrysanthemum vase as a different strand of inquiry and achievement. All three were made in May or June 1915, when Galner pushed the boundaries of her artistic expression and radically transcended the abilities of her fellow decorators. A massive vase or lamp base decorated with Queen Anne’s lace features a free-form, asymmetric composition of bold white flowers rising confidently before bands of blue, representing water, horizon, and sky (Fig. 10). Exquisite detailing in the stylized green vegetation at the base is carefully delineated with strong black outlines, which extend upward in the stems and culminate with the frenzied articulation of the blossoms.

A similarly tall vase is decorated with five colossal irises and ten unopened buds (Fig. 13). A mysterious watery veil suggests a marsh at the base, from which rises an intricate field of iris leaves and stalks that trail back into perspective. Duos of unopened buds, each decorated with its own details and glazed in taupe and dark and light blues, flank each huge flower, which stands tall against the brooding indigo shades of twilight. The placement at the vase’s shoulder of the five large irises is perfect, exuberantly presenting a quintet of individual “personalities,” some blossoms jutting up out of green sheaths and others standing singularly. Each flower is superbly rendered with elaborate outlining, two or three shades of blue, and a feature unknown on any other Saturday Evening Girls vase—meticulously applied yellow highlights. The artistic effects of these two colossal ceramic achievements are vastly different, but taken together they represent a high-water mark for Galner and for the Saturday Evening Girls, comparable to the very best of competing potteries around the country.

The third vase made by Galner in these two creative months in 1915 is considerably smaller but offers a strikingly distinct decorative approach (Fig. 12). Rather than repeated elements like the nearly identical chrysanthemums, a varied landscape densely populated with Queen Anne’s lace, or repeated irises with significant variations, this vase effectively presents a single landscape unfolding around the vase. From two angles, bunches of gorgeous irises in blue hues and various unopened buds cluster, with a few of the blossoms slyly poking up into the upper green band. These striking arrangements give way to a complex horizon with two irises that act as pillars to frame a lake or sea, bright yellow sunrise or sunset, clouds, and carefully shaded indigo skies above. The atypical decoration is arresting, offering a variety of approaches to its imagery. Its relatively smaller scale slows the viewing experience; its beautiful features reward long, careful attention.

Some Saturday Evening Girls objects that may appear more utilitarian nevertheless achieve an extraordinary blend of art and craft. A bowl decorated with nasturtiums (Fig. 11), in detailed cuerda seca, recalls the exemplary ornamentation seen in the finest of works from the Paul Revere Pottery. Rather than delineating the flowers in contrast to bold backgrounds as in other works, here Galner carefully enmeshed the decoration within surrounding bands of color, pairing a green band with the leaves, a taupe band with some of the blossoms of the same color (perhaps those in shade), and a yellow band with brilliant buttery flowers. The sophisticated juxtaposition of these fields of color and the corresponding and contrasting botanical scheme creates a tense, latent energy. This bowl rewards close observation. The cluster of flowers appears six times around the bowl, but the clusters have 5, 5 ½, or 6 blossoms. The repetition is also subtly disrupted by one cluster of nasturtiums in which one typically yellow and one typically taupe blossom are reserved in position.

The range of ceramics created by the Saturday Evening Girls of the Paul Revere Pottery has easy appeal, but rewards careful attention. Some of their seemingly utilitarian objects were significant achievements in design. Their masterwork vases stand among the finest works of American art pottery.

1 An excellent history of the Saturday Evening Girls and Paul Revere Pottery can be found in Nonie Gadsden, Art and Reform: Sara Galner, the Saturday Evening Girls, and the Paul Revere Pottery (Boston: MFA Publications, 2006). A fine condensed history and helpful information can also be found in Alice Cooney Frelinghuysen, Martin Eidelberg, Adrienne Spinozzi, American Art Pottery: The Robert A. Ellison Jr. Collection (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art/New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), pp. 247–252. I am grateful to Nonie Gadsden, Nonnie Frelinghuysen, Adrienne Spinozzi, Barbara Nitchie Fuldner, and Marilee Boyd Meyer for information and access to objects and photographs in preparing this essay. 2 This topic is honestly and clearly discussed in Frelinghuysen, Eidelberg, Spinozzi, American Art Pottery, p. 248, where the quoted phrases appear. 3 An Independent Woman: The Autobiography of Edith Guerrier, ed. Molly Matson (Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992), p. 85. 4 Though the lid to this jar is lost, another lidded jar is known to the author. This model features a Viking revival ship motif, with ships treading through water and a beautiful wave pattern elegantly integrated on the lid. 5 Frelinghuysen, Eidelberg, Spinozzi, American Art Pottery, p. 248. 6 Quotations from Arthur Wesley Dow, Composition, 7th ed. (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Page and Co., 1913), pp. 24–25. 7 Mary Harrod Northend, “Paul Revere Pottery,” House Beautiful, vol. 36, no. 3 (August 1914), p. 83. 8 Paul Revere Pottery Inc. (Brighton, MA, n.d.), n.p. 9 A fourth excellent vase from this moment of productivity is in the collection of Historic New England. Decorated by Lili Shapiro (1894–1978) with a regular pattern of yellow tulips and dated June 8, 1915, it is related in size and shape to the second iris vase discussed here, and can be seen in “Collections” at historicnewengland.org. I am grateful to Adrienne Spinozzi for pointing out a fifth vessel, a lamp base in the collection of the Museum of the City of New York, dated May 1915. This beautiful work by Albina Mangini features complex bands of green, yellow, and blue, and yellow iris buds and blossoms.