Note 1. Why subject myself?

Visiting an art fair has yet to prove a waste of my time. The satisfaction I take from attending these events is almost ensured by the realistic expectations I have in anticipation. In the first place, news of an upcoming art fair arouses my curiosity. Every art fair is a marketplace with some guiding theme or point of view. I think of an art fair as a store, or maybe warehouse, filled with a curated inventory. Instead of, say, groceries, paintings and sculptures are on offer, selected for their beauty, materials, size, political messaging, maker, cultural history, or any number of marketable ingredients. Like a plentiful buffet, these wares are conveniently served all in the same place to tempt one’s appetite.

Note 2. The lay of the land: delight or dismissal

Part of the challenge when visiting an art fair is negotiating the sheer volume of it. I enter, show my ticket, and adjust to the floor plan. Booths often rub right up against each other along corridors, or in some other labyrinthian maze. A map might be provided to guide my route. Because every installation beckons for customers, or at least viewers, it can feel exciting, or overwhelming, or both. It is up to me whether to be drawn in by a dealer’s bid for my attention. I am a free agent who chooses where to spend time. Choosing is part of the adventure. Every dealer’s booth presents a tiny universe, an environment created explicitly for these goods.

This is a decadent exercise. A booth’s walls, floors, and lighting have been to varying degrees designed to create some desired mood. I am amazed—dazzled, really—to consider how much money and effort are spent each time a temporary fair opens for business. Is it an interior that seems all of a piece? For example, in shows of traditional nineteenth-century or even older art, I’ve often noticed a preference for using dark value walls and dim overall lighting that help to focus attention on highlighted paintings or sculpture. Every object looks carefully positioned. Booths like this feel quieter to me and reference a kind of serenity you might find in a museum. They present an aura of seriousness. Or the dealer may want to produce a brighter, louder, more contemporary effect within which to display a more diverse selection of works. That feels more like aiming to offer something for everyone. Booth preparation is fascinating nonverbal messaging. I also notice the dealer’s on-site office, more or less discreetly built into the environment. Finally, each environment is inhabited by the dealers or staff, who may exude an uncanny reflection of the booth’s style.

I check the name of the gallery and note their place of business before heading in. I think of it as entering their lair. From past experience I know that they will adopt some tack on how much and exactly when to interact with booth visitors. It’s a skill set, a strategy that shows up as I approach. All this is part of the package that I take in with some interest.

Note 3. Visiting the artwork

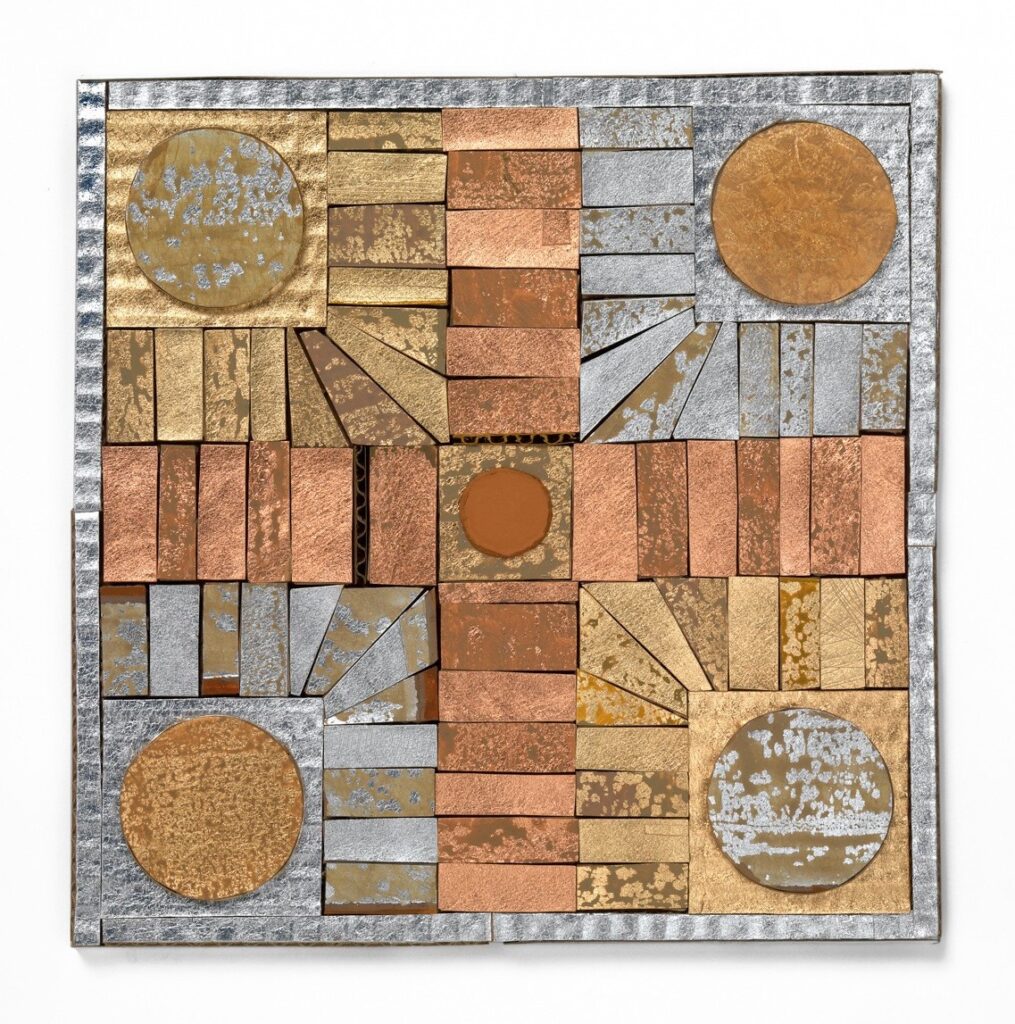

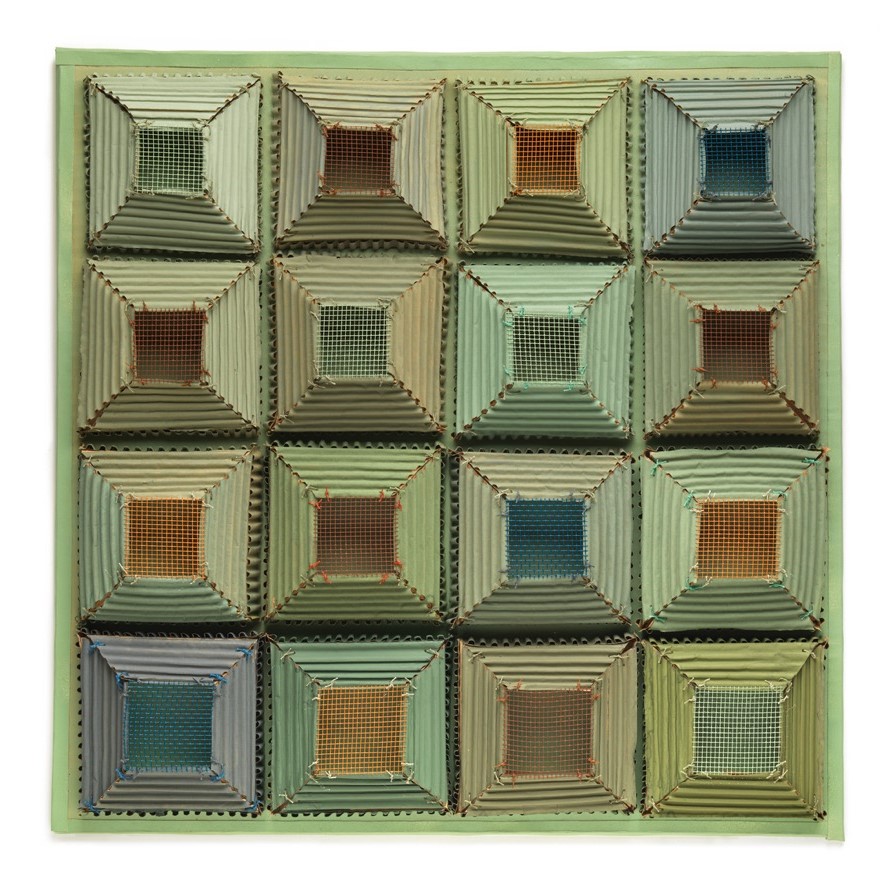

It takes at least one artwork of interest to lead me into a dealer’s booth. It might be a familiar piece that I now have the opportunity to see up close. Or it is the work of an artist I admire. Perhaps the subject matter is already on my mind. More often, it’s just a work that calls out to me for its materials, color palette, form, composition, novelty—maybe all of the above.

That is the mystery and glory of exercising personal taste. To visit a piece of art (on its own terms) is why I come to an art fair. To me, seeing an artwork means witnessing, appreciating its formal content first. It’s as if I’m looking through the piece, beyond any recognizable reference or function. I study how it became this object before me, and the myriad decisions its creator made in the process. I examine the materiality of its paint, its paper or canvas, and absorb all the technical ways these elements have been transformed into something else. It may in fact be a clay vase in which to arrange a bouquet of flowers (its transactional job), or an oil painting that records a real world landscape. That recognition comes after I have seen all the details of its aesthetic vocabulary. There is perceptual pleasure in this. By its very nature, entering a work also means disregarding its surrounding hectic chatter and energy. For a few moments, everything else in the room falls away. There is only the work and me viewing it. It’s a little like being in love.

Note 4. An aside

When and if viewing art gets too intense, I can always pause to observe the other visitors! I stand back against the wall or find a bench—a vantage point from which to watch the art fair audience travel by. This is another sort of visual wealth, the people visiting the fair, their faces, their fashions. It’s a whole other show in which to engage. If an art fair is so big that I am satiated with looking before I’ve finished my route, there might be a café where I call an intermission. Always a helpful respite.

Note 5. Personal inspiration

There often exists, somewhere in the fair space, art that speaks directly to my current projects—pieces that inform and can be applied to my own art making. Being able to see and study them is an extra reward. I usually bring a notebook with me, and of course it’s easy enough to photograph anything now. But I do still feel uncomfortable taking pictures of other people’s art. They have so much value for me, it seems like a theft.

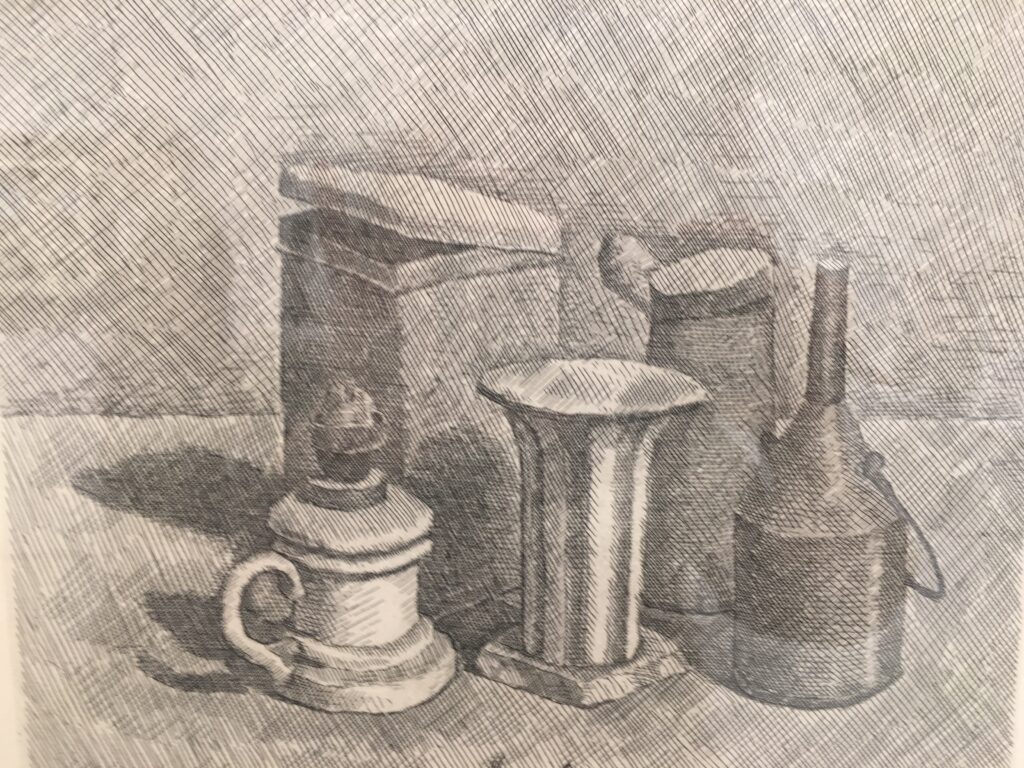

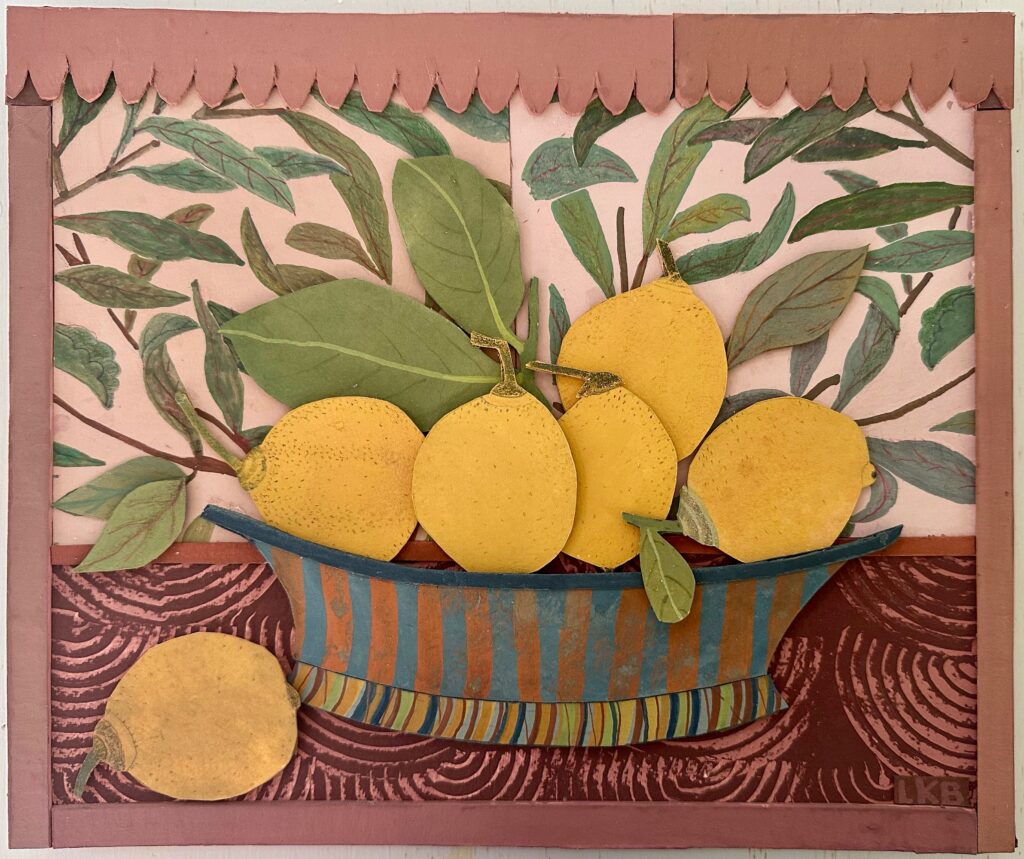

It is my great good fortune to come upon a piece of art that reveals something specific about what I am doing. With contemporary art, I occasionally get to meet and speak with the artist whose work is on exhibit. For example, I have been adding to a body of still-life collage for a few years now. Given the sheer longevity of still life as a genre, there’s a good chance I will come across some examples at any given art fair. Visiting these works brings a special pleasure because it always educates me in some way, even when it tells me what not to do.

Lessons in framing also enhance my art fair experience, especially when many works by the same artist are framed differently. This easy opportunity to compare and contrast their effectiveness is ripe for the taking.

All this has been handed to me. I am grateful.

Note 6. Art fairs showcasing antiques

Extra layers of history come along when an art fair features antiques. The older an object, the longer its story. What is its prior ownership (provenance)? Where is its place in a country’s material culture? How good a specimen is it within its genre? Do we know who made it? Its backstory accompanies the aesthetic vocabulary of any piece of art.

Doing justice to describing an antique requires historical expertise. There is, as well, the history that shows up on the object itself, the wear of time and patina visible on its surfaces. Dealers in antiques usually are well informed about their inventory. Just by asking, I learn about the furnishings or other objects I admire. Longer life, more storytelling. I am a huge fan of American antiques and folk art. When art fairs feature such material, it is like visiting my people. So many times, I have found inspiration in this work, be it nineteenth-century quilts, basketry, game boards, theorems on paper, or painted furniture. Their beauty and craftsmanship often extend far beyond any utilitarian function.

The fact that these works are so accessible and at least theoretically could be purchased adds another dimension to all this looking. There is an edge of excitement to buying and selling that steams up in the booths doing business. It’s an efficient way to shop, too, if you are looking to buy: one-stop shopping. My game is always to imagine that I’m allowed to take home one piece, and so must make a final selection before leaving. This is me honing a muscle or skill of choice.

Note 7. The marketplace for fine art

There has been much conversation about the effects these commercial trade shows have on our perception and appreciation of fine art. Does it honor fine art more or less, being for sale on the floor? It is being treated like any commodity now that we have removed it from the cathedral and the museum. Yes, its value can be bartered in terms of price; however, with good art, there is always additional, unmeasurable value. Like any market, an art fair can be noisy, crowded, and somehow superficial.

But art fairs serve other purposes to good effect. Exposing viewers to so much material is something of an education. The very informality of a fair may make fine art seem friendlier, more within the grasp of people who otherwise are intimidated by galleries and institutional settings. It can be fun visiting an art fair—there’s so much energy. It has probably changed the whole tilt of how dealers make their living, but that is the subject of another essay. As an artist visitor, for me an art fair is a gift.