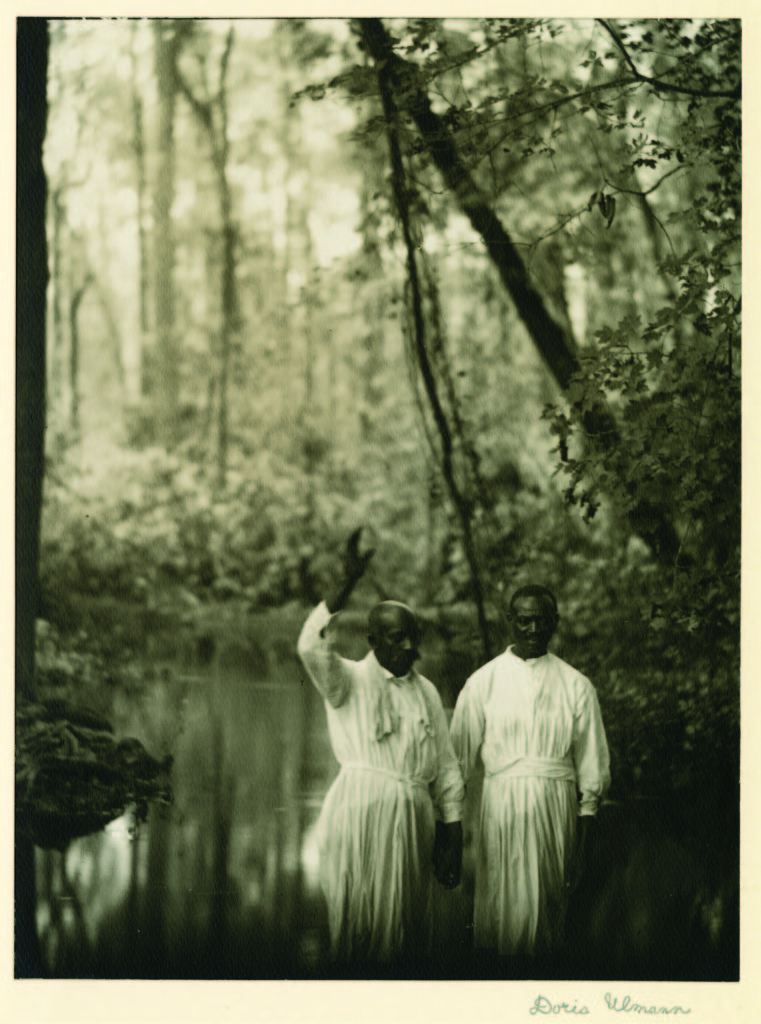

Fig. 2. Preparing for Baptism by Doris Ulmann (1882–1934), c. 1929–1931. Signed “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Photogravure for the book Roll, Jordan, Roll (1933), 8 by 6 inches. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, New York; photograph courtesy of Berea College Art Collection, Berea, Kentucky, © Doris Ulmann Foundation.

While not among the best known American photographers of the early twentieth century, Doris Ulmann is one of the most intriguing. A native New Yorker, she worked primarily as a portraitist throughout her career, which lasted from roughly 1915 until her death in 1934. In its early stages she ran an informal portrait studio in her Manhattan apartment, but for the last seven years before her death she spent extensive time traveling in and photographing the people of rural areas in the eastern United States, particularly in Appalachia and the Southeast. Ulmann’s evolution as a photographer—in style and subject—places her in a unique category among her peers.

Fig. 3. Hands Holding Hammer and Horseshoe, c. 1933, printed by Samuel Hector Lifshey (1871–1954), c. 1934 – 1937. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Gelatin silver print, 6 by 8 inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in the Berea College Art Collection, © Doris Ulmann Foundation.

When Ulmann’s photography is discussed in histories of art, which is not often, she is described as either a pictorialist—one in a group of photographers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who often deliberately blurred their work for an atmospheric effect—or a documentarian, a term that has many meanings in the history of photography. Neither label quite suits, as demonstrated by a major exhibition at the Georgia Museum of Art: Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann.

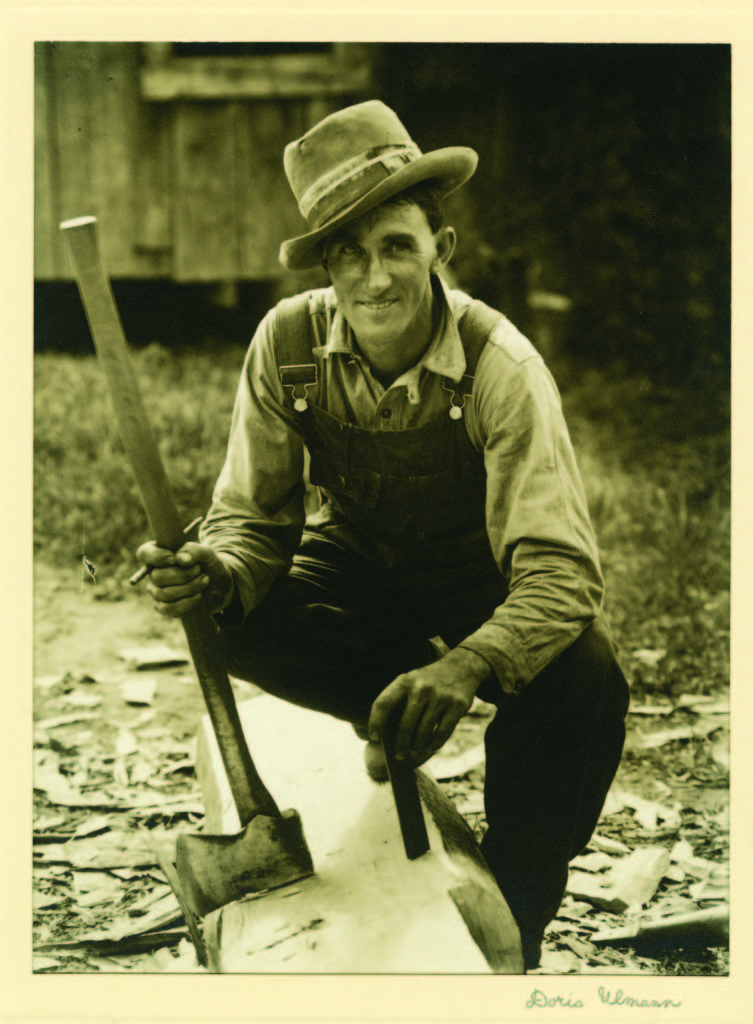

Fig. 4. Mr. Stewart, Crosstie Maker, c. 1933, printed by Lifshey, c. 1934–1937. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches.

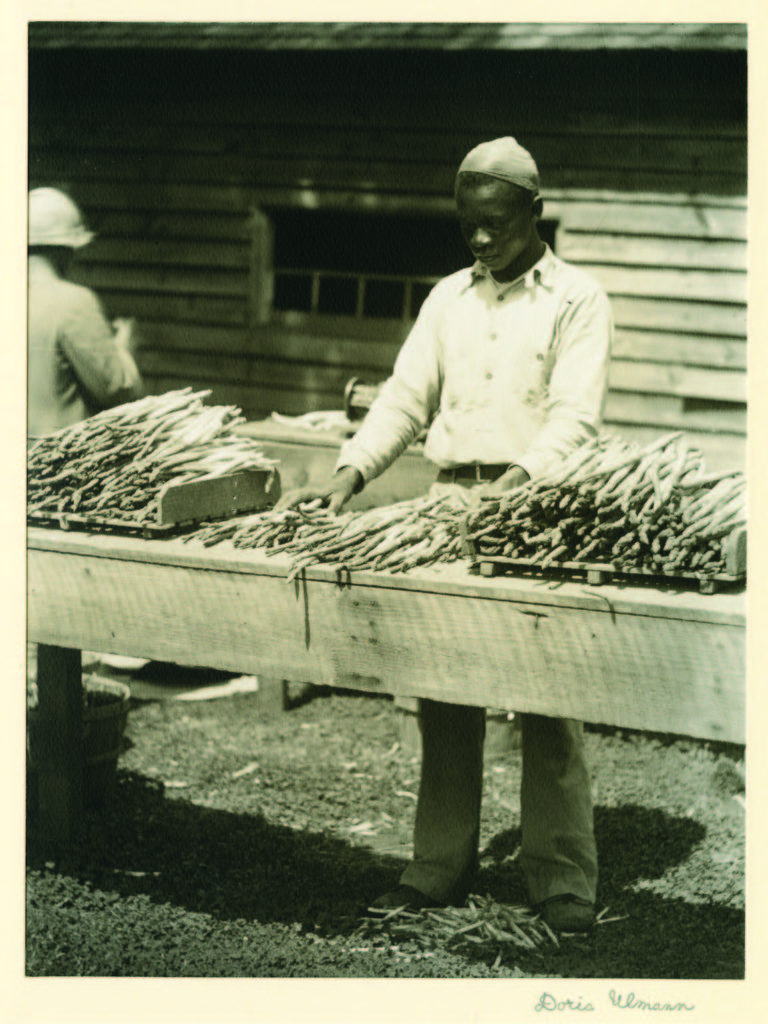

Fig. 5. Man Sorting Asparagus, date unknown. Stamped “Doris Ul- mann” at lower right. Photogravure, 8 by 6 inches.

Although she worked in the same period and in the same city as the circle of artists associated with high modernist Alfred Stieglitz, Ulmann never attempted to align herself with that group or with any other burgeoning American modernist movement, nor have scholars or critics generally considered her work modernist. Why, then, bring up modernism in relation to Ulmann’s work? The answer brings with it a host of concerns surrounding the history of modernism in the United States and how it has been defined. In the first decades of the twenty-first century, scholarship has witnessed a shift away from a definition of modernism qualified only by a series of formal breakthroughs based on artistic trends in Europe.1 Instead, historians and museums have begun to pro er a more expansive definition of modernism, including genres previously left out of the definition, such as American Scene or regionalist painting and the work of self-taught artists.2 This exhibition and its accompanying catalogue are an attempt to enter Ulmann’s work into this broader conversation and, in so doing, to offer a reevaluation of her career and her photography as a whole. Excluding the occasional mention in a broader text on the history of photography, much of the current discussion around Ulmann’s work has been biographical or general in nature.3 There have been several smaller, focused exhibitions of her work, but this show is the first comprehensive examination of her prolific output, treating the entire range of her career.

Fig. 6. Doris Ulmann Holding Tripod attributed to John Jacob Niles (1892–1980), c. 1930, printed by Lifshey,

c. 1934–1937. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches.

Despite the divide that grew between pictorialism and what has been labeled modernism, there was also considerable crossover among the people in these groups in the early decades of the twentieth century, and Ulmann was part of that. During her life, she exhibited with many photographers considered strict modernists, such as Imogen Cunningham, Edward Steichen, Man Ray, Edward Weston, and Charles Sheeler. Her work was not shaped by the tenets that typically constitute traditional pictorialism. She rarely created the atmospheric, staged, tableau-vivant– like imagery that primarily defined the movement, as practiced by her teacher, the well-known pictorialist Clarence H. White. Over the twenty years or so of her production, Ulmann’s work moved from exhibiting some of the typical features of pictorialism—such as blurred and softened edges—to a crisper, sharper, and more streamlined aesthetic.

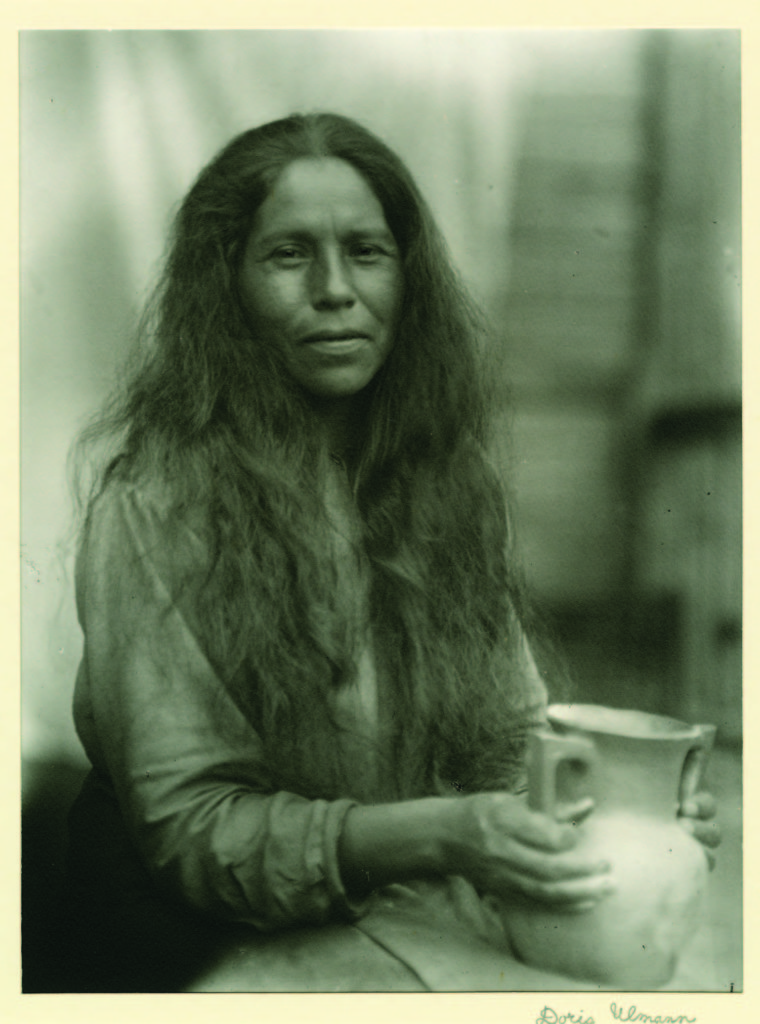

Fig. 7. Cherokee Woman with Pot, c. 1933, printed by Lifshey, c. 1934–1937. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches.

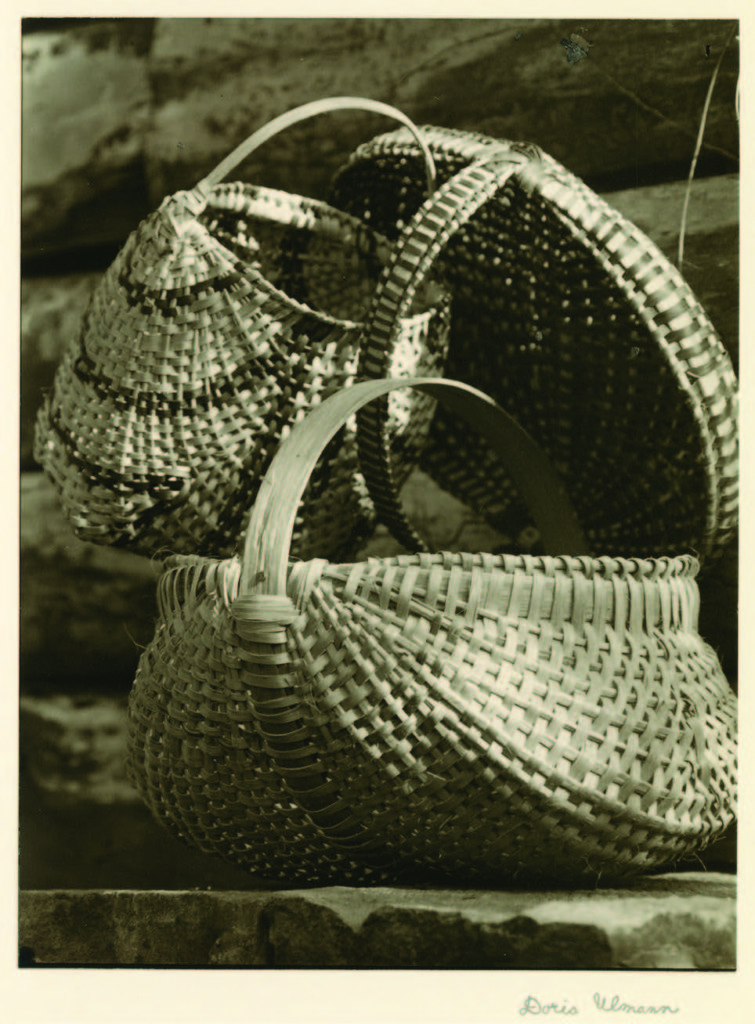

Some scholars attempt to situate Ulmann as a documentary photographer, but her work does not fit into that category either.4 The best-known definition of documentary photography is that it involves work created in the service of social reform movements, which evolved in the early twentieth cenury from the muckraking practices of photographers like Jacob Riis and Lewis Hine, whose images exposed the hideous living and working conditions endured by the urban poor. These practices inspired the documentary photography of the 1930s, particularly that executed under the aegis of Roy Stryker at the Resettlement Administration, and later by the Farm Security Administration. Although much of Ulmann’s work focused on rural people, as did the RA and FSA photography, it cannot be fully aligned with this style. With the exception of her photographs for the book Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands, published by the Russell Sage Foundation in 1937, Ulmann never created work under the auspices of any social body.5 While she certainly wanted to preserve ways of life, particularly in Appalachia, that she and others feared were disappearing, she was not seeking to engender social change with her photography in the same way that others did. As with pictorialism, Ulmann’s work has some documentary impulse, but does not wholly belong to that discursive space.

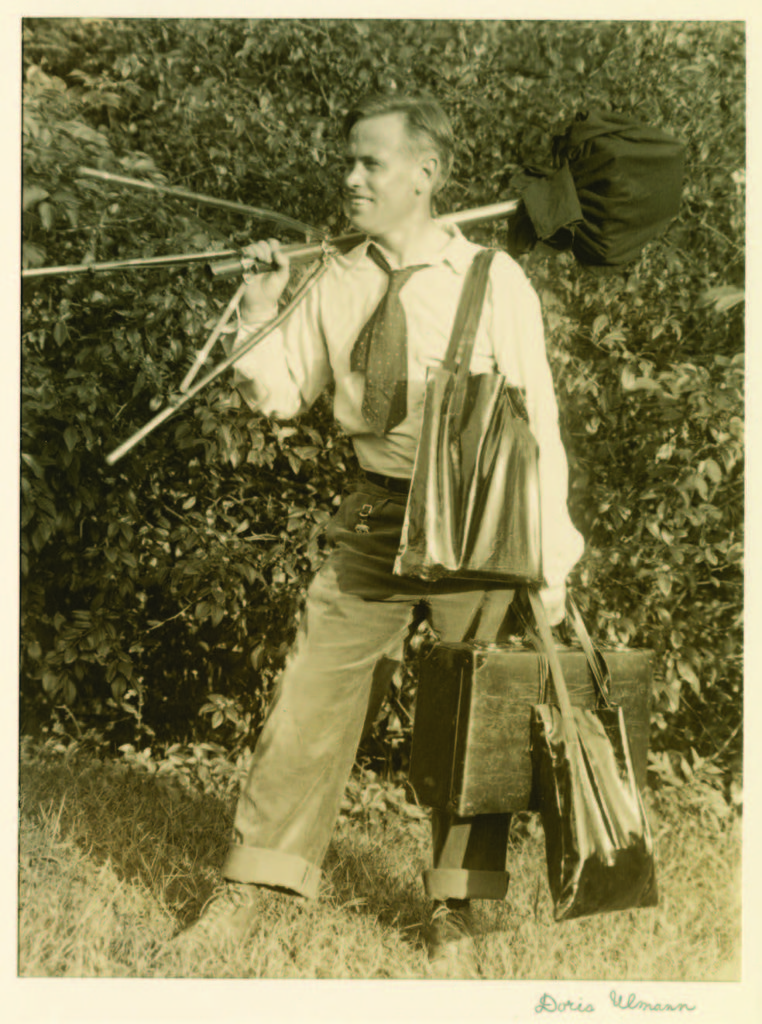

Fig. 8. John Jacob Niles Carrying Photography Equipment, c. 1933, printed by Lifshey, c. 1934– 1937. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches.

Fig. 9. Member of the Order of Sisters of the Holy Family and Child (Probably a Student), New Orleans, Louisiana, 1931, printed by Lifshey, c. 1934– 1937. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches. Bequest of Doris Ulmann.

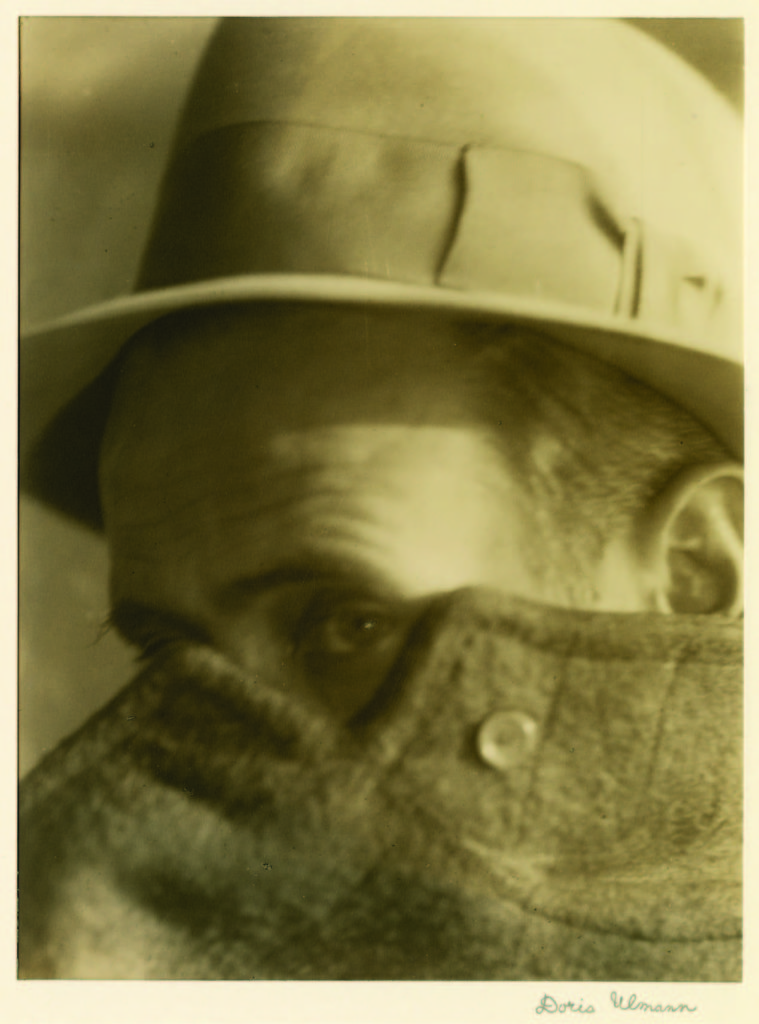

Ulmann was an artist ahead of her time. She produced Roll, Jordan, Roll (1933), a photographically illustrated book focusing on rural people with text by the southern novelist Julia Peterkin (see Fig. 2), years prior to more well-known collaborative examples by FSA photographers such as Walker Evans and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Indeed, Ulmann and Peterkin’s book is the only collaborative endeavor by a writer and photographer from that era that focuses on the lives of African Americans and the only one produced by two women. She also produced a series of intimate photographs of her companion, musician, and musical archivist John Jacob Niles, in a manner we typically associate with male photographers of the era (Figs. 8, 10).

Fig. 10. John Jacob Niles with Hat Pulled Low, c. 1927–1934. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Platinum print, 8 by 6 inches. Bequest of Doris Ulmann.

Fig. 11. Baskets, Wooten, Kentucky, c. 1933, printed by Lifshey, c. 1934– 1937. Stamped “Doris Ulmann” at lower right. Gelatin silver print, 8 by 6 inches.

This exhibition presents Ulmann’s work along- side that of her contemporaries, including Stieglitz and Paul Strand, as well as that of other artists such as Sheeler who explored the elision between the modern and the agrarian, or who depicted rural people, such as Evans and William H. Johnson. From Ulmann’s early experimental abstractions to her New York City portraits of authors, professional women, and African Americans; to her capturing people of color in the rural South and her focus on Appalachian crafts and craftspeople, the show casts a bright, intensive light on this photographer and her work.

Vernacular Modernism: The Photography of Doris Ulmann is on view at the Georgia Museum of Art in Athens, Georgia, through November 18. The exhibition is accompanied by a catalogue published by the museum.

1 For a discussion on the historical division between Americanists and modernists in the field of art history, see Richard Meyer, “Mind the Gap: Americanists, Modernists, and the Boundaries of Twentieth-Century Art,”American Art, vol. 18, no. 3 (Fall 2004), pp. 2–7. Meyer also organized a symposium on the subject at Stanford University in April 2014, entitled “Mind the Gap: On the Modernist Divide in American Art/History.”2 One of the first major texts to question the dominant narrative of a one- way transmission of modernist ideas from Europe to the United States was Wanda M. Corn’s The Great American Thing: Modern Art and National Identity, 1915–1935 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1999). Corn successfully established the notion that European artists in the period between the world wars were responding to American trends as much as Americans were considering European innovations.3 Some examples include William Clift, The Darkness and the Light: Photographs by Doris Ulmann, pref. by William Clift, with A New Heaven and a New Earth by Robert Coles (New York: Aperture, 1974); and David Featherstone, Doris Ulmann: American Portraits (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1985); as well as Philip Walker Jacobs, The Life and Photography of Doris Ulmann (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001) 4 Most notably, Melissa A. McEuen, Seeing America: Women Photographers Between the Wars (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2000). 5 The Russell Sage Foundation was established to aid the improvement of living and social conditions within the United States. See Maren Stange, Symbols of Ideal Life: Social Documentary Photography in America, 1890– 1950 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), p. 64.

SARAH KATE GILLESPIE is the curator of American art at the Georgia Museum of Art.