When architect Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956) and painter Koloman Moser (1868–1918) established a modest metal workshop in Vienna in May of 1903 to fabricate “good, simple domestic requisites,”1 they may have never imagined that their enterprise would grow to be so grand in scope and international in reach, with locations throughout Europe and even in the United States. By the end of 1904, the firm offered a wide range of wares and services, encompassing everything from bookbinding and leather goods to furniture and interior design. As the Wiener Werkstätte—Vienna Workshops—grew, its principals aspired to offer clients a “total work of art”—an immersive design experience touching all aspects of life. As part of this aim, fashion became an area enthusiastically embraced by the firm. A couture atelier was launched in 1910, and it soon proved to be the company’s most profitable department. Three artists who helped propel the fashion department to fame were Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill, Max Snischek, and Maria Likarz-Strauss.

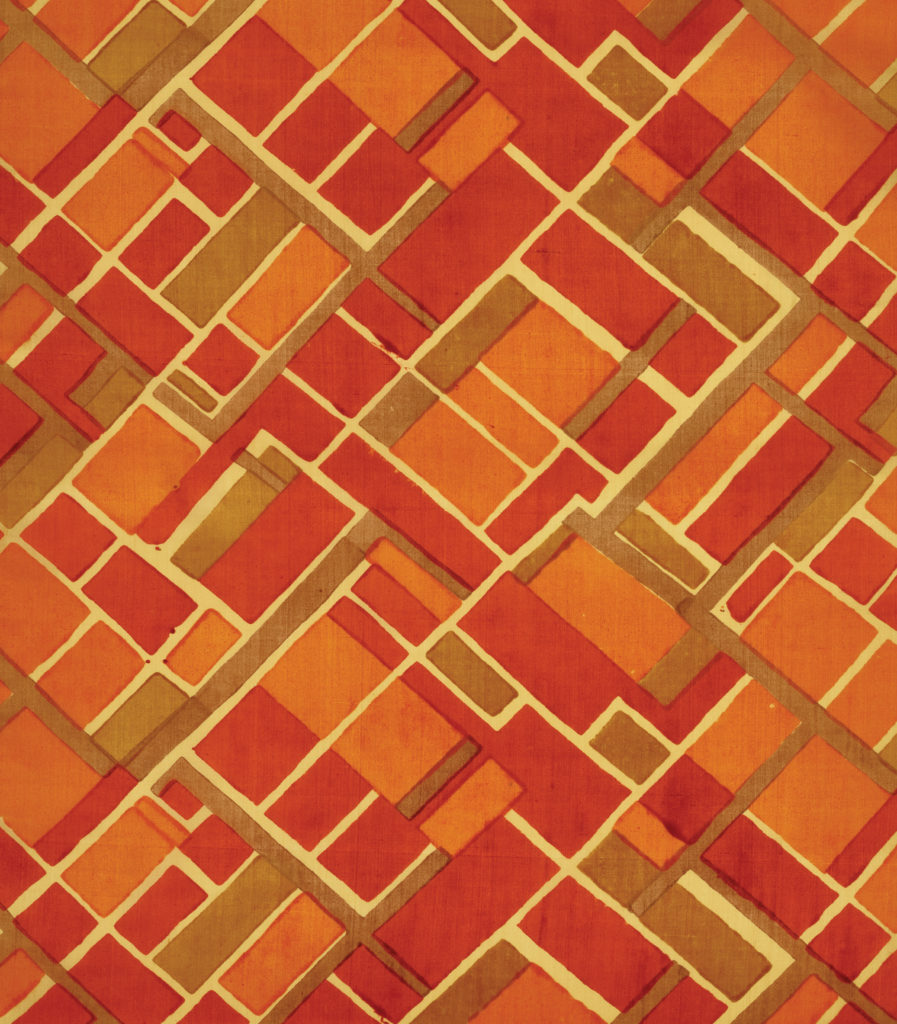

Fig. 1. Detail of New York textile sample by Max Snischek (1891–1968), Vienna, 1928. Screen-printed cotton, 15 3/8 by 35 7/8 inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in MAK – Austrian Museum of Applied Arts / Contemporary Art, Vienna,© MAK.

An interest in women’s fashion was both personal and professional for Hoffmann and Moser. Each purportedly designed unique dresses for their wives. Likewise, one of the first interior design commissions of the Wiener Werkstätte was to outfit the Schwestern Flöge (Flöge Sisters) fashion salon in 1904, a project most likely garnered through Gustav Klimt, who was close to Emilie Flöge, one of the salon’s cofounders. Not only did customers of the Wiener Werkstätte patronize the Schwestern Flöge but Emilie Flöge herself modeled Wiener Werkstätte fashion and jewelry in a notable example of cross-promotion (Fig. 4).

Fig. 2. Detail of Zyprian textile sample by Snischek, 1924. Blockprinted silk. © MAK / Georg Mayer.

Hoffmann and Moser were professors at Vienna’s Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Applied Arts), and they had ready access to the talent needed to work in diverse fields. Many of the approximately two hundred artists who contributed designs to the firm were their students. One of the first to be employed at the Wiener Werkstätte as an “artistic collaborator”2 was Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill.

Trained as an architect, Wimmer—as he was known—was a prolific designer who turned his hand to fashion, jewelry, metalwork, postcards, and textiles. He studied under Hoffmann, who subsequently invited him to join the workshops. In late May 1910, the Wiener Werkstätte applied for a license for dressmaking, and by that summer it was selling women’s fashion in the spa resort of Karlsbad. As the founding director of the fashion department, Wimmer wrote Hoffmann from the town (today, Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic) to report on the venture. He noted that although “the business in itself was rather fun . . . the female junk and clients milling around was just about the limit.”3

Fig. 3. Knit dress attributed to Snischek, Vienna, 1921, in a period photograph by Franz Loewy, Vienna. © MAK.

The Wiener Werkstätte received licenses for dressmaking and millinery in March 1911; the dressmaking license was issued to master tailor Marianne Zels.4 It cited stores on the Graben, Vienna’s prominent shopping thoroughfare, and in Karlsbad (Fig. 10). A photograph from around 1911 of the Wiener Werkstätte’s main location on the Neustiftgasse shows hats in the background (Fig. 8). In late April 1911 the firm held its inaugural fashion show, which featured designs by both Hoffmann and Wimmer.

Wimmer was referred to as the “architect of fashion.”5 He was inspired by the couture example of the French, and his clothes have a distinctly Parisian flair, inspiring the press to dub him the “Poiret of the Viennese,”6 in reference to the famed French couturier Paul Poiret (1879–1944). Poiret visited Vienna on two occasions concurrent with the establishment of the Wiener Werkstätte’s fashion department. On his first visit, in 1910, Poiret was so enchanted by the example of the Wiener Werkstätte that shortly after his return to Paris he established a similar enterprise there. Poiret even used Wiener Werkstätte textiles in his own designs. In November 1911, he hosted a fashion show in Vienna at the Urania, an art nouveau observatory and cultural facility (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Emilie Flöge (1874–1952) wearing an embroidered silk dress designed by Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill (1882–1961) and jewelry by the Wiener Werkstätte in a photograph by D’Ora-Benda Studio, Vienna, November 1910. Austrian National Library, Vienna.

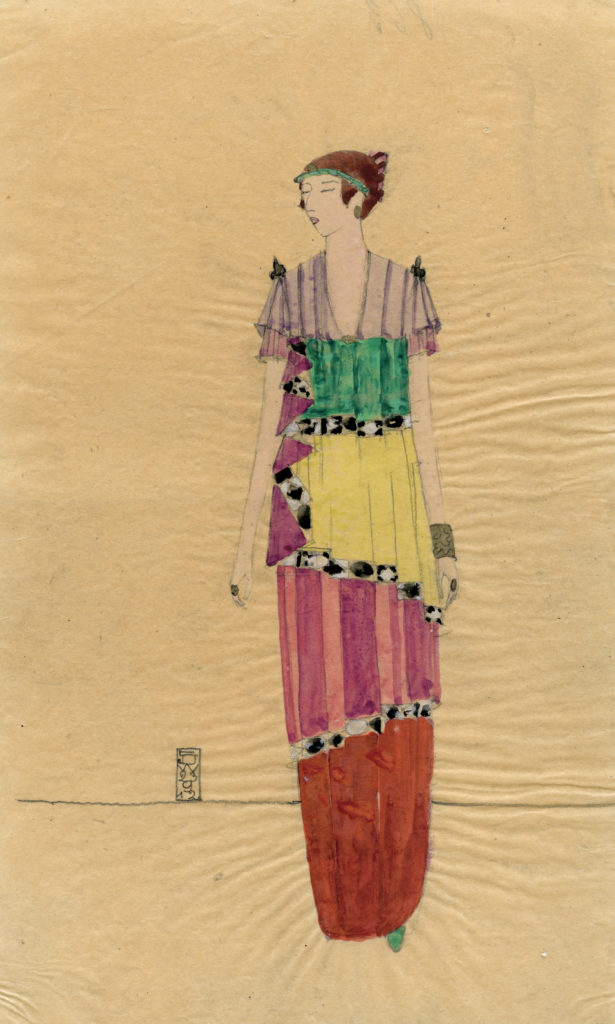

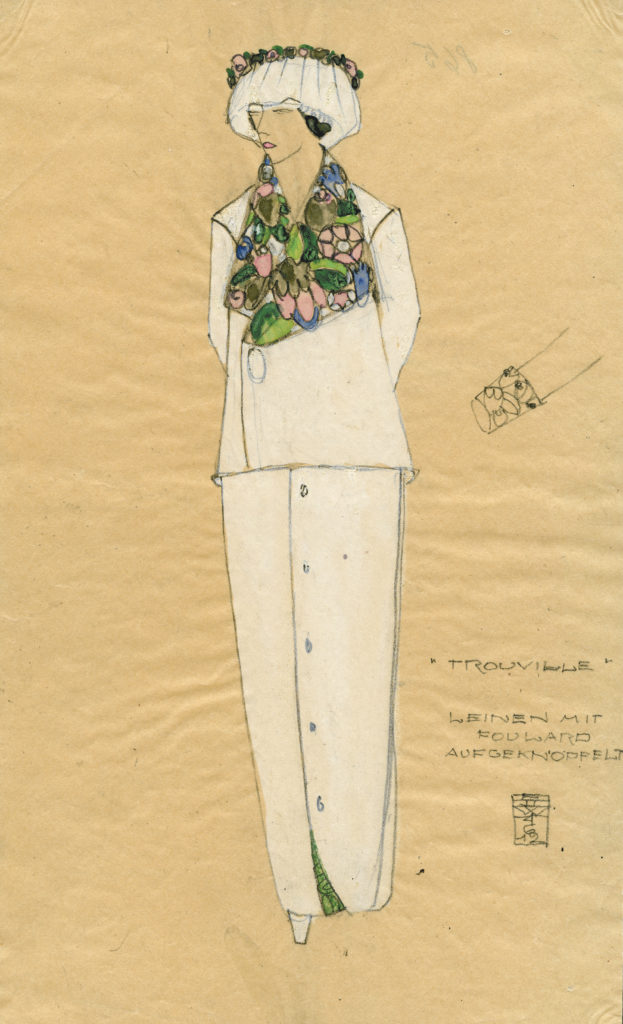

Wimmer’s couture designs were admired for their strong artistic conceit. When the Wiener Werkstätte presented a fashion show in Berlin in 1913, an account of the presentation described it as “not the usual ‘modern’ fashions, but original creations to artists’ designs, often bizarre, but . . . nearly always also pretty, or at least interesting . . . However, most of the dresses have a bit too much of an art-studio atmosphere about them.”7 Wimmer often titled his fashions as if they were works of art (see Fig. 9), such as the afternoon ensembles Diabolo (1912), Aurelia (1912), Girl from Abroad (1913), and Philomene (1918). Wimmer’s work is characterized by his use of naturalistic motifs, including “bell-shaped flowers, heart-shaped leaves, or trellis effects with ivy or roses,”8 largely inspired by folk textiles, which were collected by Hoffmann, Klimt, and others. This ornate emphasis was a shift away from the geometric forms that characterized the early work of Hoffmann and Moser for the Wiener Werkstätte.

Fig. 5. Poster for a Paul Poiret fashion show in Vienna, 1911. Colored lithograph, 33 3/4 by 21 1/2 inches. © MAK / Georg Mayer.

Just before the outbreak of war in 1914, the firm was forced into a new direction when its first financial backer, textile industrialist Fritz Waerndorfer, was no longer able to cover the recurring operating losses. As a result, the Wiener Werkstätte was reorganized and reestablished as a limited liability company. Various individuals became shareholders, including both Hoffmann and Wimmer. The firm also shifted from an almost exclusive focus on handmade fabrication to a greater reliance on machine production. A survey of the staffing allocations at the end of 1914 underscores the importance of women’s fashion for the firm. The leather and bookbinding department had five staff members, the metalwork and silver departments had nineteen between them, while the fashion department had thirty-four.

Fig. 6. Belt buckle by Wimmer, Vienna, 1910. Silver and malachite, 5 1/8 by 3 1/8 inches. © MAK / Katrin Wisskirchen.

These changes coincided with the Wiener Werkstätte’s participation in the 1914 Deutsche Werkbund exhibition held in Cologne. Hoffmann, who was vice president of the Austrian Werkbund, designed the Austrian Pavilion and Wimmer designed the room for the Wiener Werkstätte’s display, which was extremely well-received. Wimmer’s Ant pattern was used for the carpet and the upholstery, while Albert Berger’s Mecca pattern was used on the ceiling and as a backdrop in a long wall vitrine. The end walls were filled with Wimmer’s fashion designs hung side by side, creating a type of fashion wallpaper.

Fig. 7. Design for a dress by Wimmer, Vienna, 1912. Pencil and watercolor on paper, 11 3/8 by 6 3/4 inches. © MAK.

With the onset of the war, many of the designers and craftsmen employed by the Wiener Werkstätte were conscripted. A new group of artists began contributing designs, most of whom were graduates of the School of Applied Arts. One who rose to prominence in the fashion department was Max Snischek, who exhibited clothes designs at the Cologne Werkbund exhibition while still a student and later participated in the winter 1915–1916 fashion exhibition held at the Austrial Museum for Art and Industry. Snischek was a prolific textile designer who also worked in enamel, jewelry, lace, and wallpaper (Figs. 1, 2). When Wimmer moved to the United States in 1922,9 Snischek assumed his place as head of the fashion department. Snischek created graphic works to promote the activities of this very successful division within the Wiener Werkstätte, including brochures and invitations. One of the most striking dates to 1929. It is notable for its English text—“Modern is what we like”—a reflection of the significance of an English-speaking clientele. Snischek’s style is sophisticated and streamlined, with traces of the angularity of art deco design. His 1928 textile New York, for example, is simple yet vividly captures the visual cacophony of the skyscrapers that formed the Manhattan skyline (Fig. 1). Snischek remained with the Wiener Werkstätte until it was liquidated in 1932. Then he moved to Munich and taught women’s fashion design.

Fig. 8. View of the Wiener Werkstätte showroom at 32–34 Neustiftgasse, Vienna, in a photograph of 1910. © MAK.

Maria Likarz-Strauss also took on a significant role with Wimmer’s departure and jointly managed the fashion department with Snischek.10 One of many women who joined the Wiener Werkstätte during the war era, Likarz-Strauss was a graduate of the School of Applied Arts, where she studied under Hoffmann. She demonstrated an innate talent for textile design and contributed around two hundred documented patterns, making her the most prolificartist in this area. In her textile patterns, Likarz-Strauss ably shifted between abstract designs and naturalistic motifs. She was equally adept with women’s clothing and accessories—creating an entire line of necklaces and handbags crafted from tiny, vividly hued glass beads (Fig. 11). Likarz-Strauss also painted some of the group’s most popular and charming postcards, including a series on hat fashions that featured chic women sporting the fashionably short hairstyles associated with liberated women. Women were granted suffrage in Austria in 1919 with the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy, and modern styles telegraphed their newfound emancipation.

Fig. 9. Design for Trouville, a dress by Wimmer, Vienna, 1912. Pencil and watercolor on paper, 11 5/8 by 6 ¾ inches. © MAK.

The Wiener Werkstätte struggled in the postwar years and never regained its previous cachet. An attempt to establish a branch in New York City in 1922 failed in less than two years. Wimmer presciently predicted that if the Wiener Werkstätte could not succeed in the United States, then it was doomed to failure. Perhaps sensing the group’s vulnerability, in April 1927 architect Adolf Loos launched an attack on it in the form of a lecture entitled “Das Wiener Weh” (The Viennese Woe). Loos mocked the “Fräuleins” employed by the firm, alleging that they occupied themselves with “handicrafts” as a way to “earn pin-money . . . until one can walk up the aisle.”11 The assembled crowd recognized the speech as an “old man’s venomous drivel,”12 and the firm’s management soon published an “Open Letter to Adolf Loos,” defending the artistic integrity of its designs and the strength of its “sales at home and abroad, especially in Germany.”13 In 1928 the Wiener Werkstätte celebrated its twenty-fifth jubilee with a lavish publication with a papier-mâchè cover jointly designed by Vally Wieselthier and Gudrun Baudisch.

Fig. 10. Wiener Werkstätte store in Karlsbad (now Karlovy Vary in the Czech Republic), designed by Josef Hoffmann (1870–1956), in a photograph from 1909. © MAK.

But sales were faltering. In 1932 the firm was liquidated and the remaining inventory—more than twenty-five hundred lots and an estimated seven thousand objects—was sold by Glückselig, a Viennese auction house. Notably, goods from the fashion department were not offered as part of the auction, “since it was still hoped that its remaining stock could be sold at full price.”14 This aspiration was most likely wishful thinking, as one former employee of the fashion department recalled that by the mid-1920s, the clientele “consisted mainly of women who were no longer young . . . mostly women in menopause—and the models were adapted to them.”15

Fig. 11. Evening bag by Maria Likarz-Strauss (1893–1971), Vienna, c. 1925. Glass beads and kid leather, 7 ½ by 5 ½ inches. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minnesota, Modernism Collection, gift of Norwest Bank Minnesota, © Minneapolis Institute of Art.

In its heyday, the Wiener Werkstätte set a standard for unequalled artistry, luxurious hand craftsmanship, and attention to detail. This standard applied to its fashion goods, too. Even during the dire economic times that marked the aftermath of World War I, Hoffmann defended the firm’s allegiance to its founding principles, asserting, “Let us, when all is said and done, rejoice that our young artists’ community has preserved, despite destruction and death, hunger and misfortune, its capacity for delight and pleasure in the beautiful ‘thing as such,’ whether or not it serves any purpose. And let us strive to safeguard this for them.”16

Wiener Werkstätte, 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty, on view at the Neue Galerie New York from October 26 through January 29, 2018, is the first American museum retrospective dedicated to the firm and its lasting artistic legacy.

JANIS STAGGS, director of curatorial and manager of publications at the Neue Galerie New York, is co-curator with Christian Witt-Dörring of Wiener Werkstätte, 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty. She also contributed to, and is co-editor of, the accompanying catalogue, published by Prestel.

1 Josef Hoffmann and Koloman Moser, “Working Program,” 1905, translated and published in Werner J. Schweiger, Wiener Werkstätte: Design in Vienna, 1903–1932 (Abbeville Press, New York, 1984), p. 42. 2 Yearning for Beauty: The Wiener Werkstätte and the Stoclet House, ed. Peter Noever (MAK, Vienna, 2006), p. 76, n. 2. Wimmer himself offered varying dates for when he joined—1906, 1907, and 1909—but Elisabeth Schmuttermeier believes that 1907 is most, likely the correct date. See Elisabeth Schmuttermeier, “Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill,” in New Worlds: German and Austrian Art, 1890–1940, ed. Renée Price (DuMont/Neue Galerie, New York, 2001), p. 487. 3 Schweiger, Wiener Werkstätte, p. 224. 4 Yearning for Beauty, p. 92. 5 Mark Wigley, White Walls, Designer Dresses: The Fashioning of Modern Architecture (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1995), p. 76. 6 Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, Berlin 1913, quoted in Schweiger, Wiener Werkstätte, p. 233. 7 “Modeschau der Wiener Werkstätte,” Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, March 12, 1913, quoted in Yearning for Beauty, pp. 101–102, n. 3. 8 Schmuttermeier, “Eduard Josef Wimmer-Wisgrill,” p. 487. 9 Wimmer subsequently took up a teaching position at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and returned to Vienna in 1925. 10 Angela Völker, “Fashion, Textiles, and Wallpaper,” in Wiener Werkstätte, 1903–1932: The Luxury of Beauty, ed. Christian Witt-Dörring and Janis Staggs (Prestel, Munich, 2017), p. 265. 11 Schweiger, Wiener Werkstätte, p. 118. 12 Ibid., p. 119. 13 Ibid. The letter appeared in the Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, April 23, 1927. 14 Völker, “Fashion, Textiles, and Wallpaper,” p. 305. 15 Ibid., p. 298. 16 Schweiger, Wiener Werkstätte, p. 108.