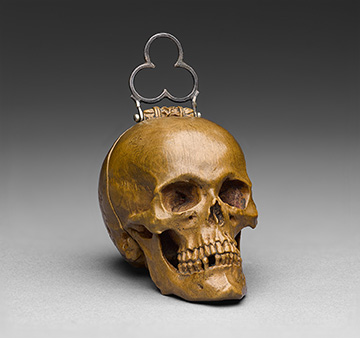

Boxwood rosary, Netherlands, 1500–1539. Musée du Louvre, © Musée du Louvre; photograph by Craig Boyko/ Ian Lefebvre.

Whether it’s Mount Rushmore or the Great Buddha of Thailand, the monumental work of art has an immediate power to inspire awe and amazement. Yet the small, intricate artwork provokes wonder of a different and, perhaps, even deeper order. These tiny triumphs speak to human ingenuity, boundless reservoirs of patience, and painstaking craftsmanship in efforts where the slightest error will ruin the whole.

Three current shows at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York invite us to revel in minutely scaled carved sculpture produced centuries ago in Europe and China, and in a variety of mediums that challenged the technical mastery and imagination of artists and craftsmen, most of whose names are unknown.

Jewels of box

Prayer bead, probably German, early sixteenth century. Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Thomson Collection, © Art Gallery of Ontario; Craig Boyko/Ian Lefebvre photographs.

At the Met Cloisters, the exhibition Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures—organized by the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), the Met, and Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum— focuses on some forty miniature sculptural works that were a specialty of the Netherlands in the sixteenth century. Meticulously carved out of boxwood, these extra ordinary works were all fashioned as personal objects of devotion in an age when such jewel-like artistry was intended to glorify the daily prayer that was elemental to European life. Boxwood, a type of ornamental tree brought to northern Europe from its native Mediterranean region, was an ideal medium for this kind of work because its hardness and close grain allowed it to be carved in such minute scale without weakening.

Each work in the show contains one or more sacred images carved in relief—biblical episodes, portraits, and miraculous events—many with numerous figures set against complex architectural or outdoor backgrounds. Since the time of their creation the astonishing virtuosity of these carvings has mystified viewers—the apparent undercutting of tiny details, perhaps carved from behind with minuscule hand tools, and the separation of the figures from the background elements of a scene would have required inconceivable dexterity.

Carved on the inside are depictions of Adam and Eve (top) and the Crucifixion (bottom). Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto, Thomson Collection, © Art Gallery of Ontario; Craig Boyko/Ian Lefebvre photographs.

The mystery was finally solved during the five years of preparation for the exhibition through the cooperative efforts of AGO’s Alexandra Suda and Lisa Ellis, together with their colleagues at the Met and the Rijksmuseum, where the show will travel this summer. The revelation—documented in an astonishing video at the exhibition—is that these works were not carved in one piece. Instead, as a disassembled prayer bead shows, it comprises carved slices fitted together in layers—like traditional scenery flats used in theaters from the Renaissance to the early twentieth century. Fastened with pins, they create the illusion of depth and natural perspective.

Among the star attractions is the beguiling Chatsworth Rosary (c. 1509–1526), now in the collection of the Dukes of Devonshire and originally owned by Henry VIII and his first wife, the Spanish-born Catherine of Aragon. A single-decade rosary, it consists of ten smaller Ave beads—each carved with four scenic roundels—a lobed cross, and a larger paternoster bead with twenty-four scenic or portrait roundels on its surface. This larger bead opens to reveal two more scenes, one of which conceals portraits of Henry and Catherine that had not been seen in some five centuries.

Hypnotic hardstones

For jewelers, “hardstone” refers to varieties of precious and semiprecious colored stones used for mosaic and inlay work such as pietra dura, and for carving into cameos and other decorative objects.

“By traditional Chinese definition, hardstones are divided into two categories: jade, which is the mineral nephrite, and all other precious and semi precious stones,” writes Jason Sun, curator of the Met’s ongoing installation Colors of the Universe: Chinese Hardstone Carvings. On view are seventy-five superb examples of Chinese lapidary work of the Qing dynasty (1644–1911): precious carvings of jade, agate, malachite, quartz, coral, and other hardstones that reveal the resplendent variety of colors in these minerals.

Peanuts and jujube dates carving, Chinese, Qing dynasty, eighteenth century. The objects illustrated are in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Heber R. Bishop.

Among the oldest of Chinese arts, hardstone carving was practiced as early as the fifth millennium B.C. But not until the prosperous eighteenth century did the combination of sufficient raw material—much of it imported from as far away as Europe—and active court patronage allow the art to thrive.

Working slowly with abrasives like powdered quartz applied to revolving steel disks powered by foot treadles, hardstone carvers ground away the rough outer surface of a gemstone or gem-bearing rock—roughing out the sculptural shape, refining the piece, and finally polishing it to a lustrous finish. From a lump of stone, these artists could produce miniature landscape compositions, animals, fruits and vegetables, and divinities symbolic of prosperity and good wishes for the eventual owner.

Water dropper in the shape of a crane, Chinese, Qing dynasty, eighteenth century.

In some instances the natural properties of the stone itself suggested the design, as in a delectably realistic composition of candied jujube dates and peanuts carved of brown chalcedony. The artist made use of the original shape and colors of the raw stone. Its rough yellow crust forms the peanut shells, and the interior was carved and polished to form the jujubes.

Another example, that reveals how these artists could visualize a finished design within a rough stone is a lyrical white agate water dropper, carved as a Manchurian crane with a branch of peaches in its beak. The agate was flecked with natural iron-red streaks, which the artist exploited to suggest the blush of the peaches; another red streak was carved as the bird’s rosy crown.

Vase with bamboo and plum tree, Chinese, Qing dynasty, eighteenth century.

To one Qing-dynasty carver, the green veins in a piece of translucent warm-toned chalcedony suggested a vase in the form of a mountainside scene: the irregular veins become graceful pine trees and bamboo canes breeze-blown along the slopes.

Seductive cinnabar

Tray with women and boys on a garden terrace, Chinese, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), fourteenth century. Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving.

A related area of Chinese carving is examined in Cinnabar: The Chinese Art of Carved Lacquer, 14th–19th Century. A far more malleable carving medium than hardstone, lacquer is produced from certain southern Chinese trees. The most highly regarded is that derived from the sap of the Rhus vernicifera tree. It is harvested as a gray, syrupy fluid that polymerizes on exposure to air, hence it is regarded as the earliest known plastic. After straining and heating to expel superfluous moisture, it is brushed in thin coats onto a matrix of wood, clay, metal, or fabric. Each coat is allowed to dry before another is applied. The many coatings yield a hard, smooth, durable, waterproof crust suited to intricate relief carving.

Naturally gray, lacquer can be tinted red by adding cinnabar (mercuric sulfide). Other minerals yield shades of brown or green. But red is considered an auspicious color in China, and much of this exquisite work—produced since the fourth century bc—is known as cinnabar lacquer or just cinnabar. The process of applying and drying layers was extremely time consuming and the carving demanded exceptional skill. Much work was executed in a single color, but some pieces had layers of different colors, creating cameo-like textures and beautiful polychrome striations when carved.

Dish with long-tailed birds and hollyhock, Chinese, Yuan dynasty, fourteenth century. Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, in honor of James C. Y. Watt.

The forty-five lacquer objects in this show represent a variety of imaginative carved designs, many of them exceedingly complex, while others show remarkable restraint. Styles and motifs help to establish their dates. For example, while the backgrounds in a great many later cinnabar pieces are carved with diaper patterns, the smooth, unworked dark background to the playfully circling long-tailed birds and hollyhocks in a Yuan dynasty dish is a feature more common in earlier lacquerwork and suggests the dish’s fourteenth-century date. The hollyhock blossoms are carved with overlapping petals of different sizes to indicate depth, and it is striking to consider that the naturalism of the birds and botanical life depicted here doesn’t appear in European art for another century.

In contrast to the intimacy of this dish, we find a virtuosic panorama in a large, roughly contemporaneous Yuan dynasty tray depicting women and boys on a garden terrace with a pavilion overlooking a lotus pond. Here twentyfive carved figures are seen at play—two of them riding hobbyhorses, which may have been a Chinese invention. Given its size and its happy documentation of privileged domestic life, the tray is regarded as a lacquerware masterpiece.

Tray in the shape of a peony, Chinese, Qing dynasty, nineteenth century. Edward C. Moore Collection, bequest of Edward C. Moore.

An asymmetrical eighteenth-century Qing dynasty confectionary box with carved lychees in red, green, and yellow shows the beautiful effects attainable with polychrome lacquers. The deep carving of the fruits—each separate from the others—and the incised lattice patterns along the sides of the box and cover typify eighteenth-century cinnabar design.

Next to the beguiling complexity of these works is the subtle understatement of a nineteenth-century Qing dynasty tray carved in red and black lacquer in the shape of a peony. Here, instead of the meticulous rhythm and texture that lacquer artists could achieve with their carving tools, the artist capitalized on the smooth, soft sheen of the open petals.

Small Wonders: Gothic Boxwood Miniatures is on view at the Met Cloisters through May 21; Colors of the Universe: Chinese Hardstone Carvings and Cinnabar: The Chinese Art of Carved Lacquer, 14th–19th Century are on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art through October 9.