The Magazine ANTIQUES | April 2009

The stunning events of July 1804 were almost unfathomable for the citizens of the new American republic. One Founding Father had fatally wounded another. Alexander Hamilton was dead and Aaron Burr would be indicted for murder. The duel and its aftermath marked a turning point in American culture.

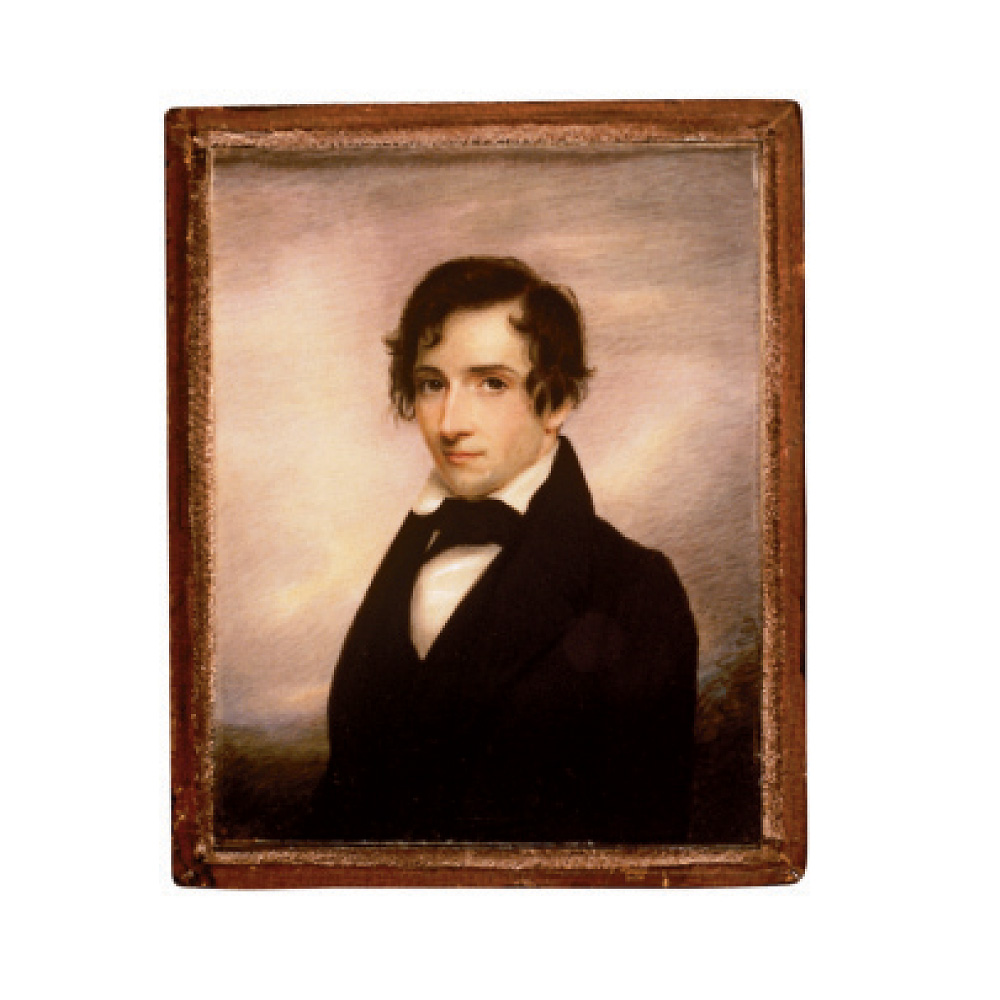

Five days before the Burr-Hamilton duel, Edward Greene Malbone arrived for a week’s stay in New York. Considered the finest miniaturist in the United States, Malbone was attractive, popular, already exceedingly successful, and only twenty-six years old. As Hamilton’s massive funeral snaked up Broadway on July 14, he was meeting twenty-five year-old Anson Dickinson for the first time. A fledgling artist, Dickinson had commissioned Malbone to paint his miniature, hoping to learn by watching the more experienced artist at work (Fig. 1).1 So absorbed was Malbone in the painting “that he neither paused himself to view the pageant nor suffered his sitter to do so.”2 Around the corner on Wall Street, twenty-five-year-old Joseph Wood and twenty-three-year-old John Wesley Jarvis had recently formed an artistic partnership. All four artists, soon to be fast friends, were young, handsome, and ridiculously talented. Within three years, Malbone would be dead, but before that, the creative cross-pollination between these four young artists would allow them to develop a singular style that could never be mistaken for anything other than uniquely American.

So pervasive was their influence that when he came on the scene in 1818, the academically trained Daniel Dickinson (1795–c. 1866), younger brother of Anson, still turned to the model established by the quartet many years before. “I adopted a style between my brother Anson’s, Malbone’s and J. Wood’s, fifteen years after my brother commenced,” he wrote.3

In the decades since the 1740s American portrait miniatures had changed little. They were small, dark, and resembled provincial British works, which, indeed, they were. The most successful artists were still either British (Archibald Robertson [1765–1835], Robert Field [c. 1769–1819]) or had trained there (Charles Willson Peale [1741–1827]). Their American patrons, eager for what was familiar, did not encourage improvement.

That was about to change.

Edward Greene Malbone

Leaving his family in Newport, Rhode Island, to establish himself as an artist in Providence, Edward Greene Malbone struck out on his own in 1794 at the age of seventeen. His earliest miniatures of 1794 and 1795 followed a standard English formula of placing the sitter in front of red drapery. Though he was painting on ivory, the young artist was not yet accomplished enough to make use of the material’s luminosity. The works are characterized by opaque watercolors and strong outlines (see Fig. 2).

Malbone advanced swiftly. By the end of 1795 his style had changed completely. The red drapery disappeared and, as illustrated in his portraits of John Corliss and his wife Susannah (nee Russell) of Providence (Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington), backgrounds were strongly hatched on a diagonal. Though his paints remained dense, his faces were gracefully modeled by deliberate cross-hatching. Continually experimenting, by 1796 Mal-bone would explore a formula that would be the forerunner to his mature style. The background of his portrait of Daniel Goodwin (Fig. 5) still displays strong hatching, but he had begun using shades of dark and light; dark at the top of the head and on a diagonal from the shoulder behind. The background surrounding Goodwin’s face is bathed in light. During this period, Malbone worked in New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, South Carolina, achieving enormous success.

In 1801 he traveled to London with his friend, the artist Washington Allston. Beginning to exploit the luminous qualities of ivory, in a likeness of Allston he silhouetted the delicately hatched and shaded face against a dark background composed of a fine net of crosshatches (Fig. 3). In addition, the unusual pose, with the head angled in three-quarter profile and seen slightly from below, is a format he would replicate in many later portraits.

On his return to the United States, Malbone was painting in a style much like the artists he had admired at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, Richard Cosway (1742–1821) and Samuel Shelley (c. 1750–1808).4 For the first time he began using washes of watercolor to take advantage of the luminosity of the ivory support, as he had seen done to great effect by Cosway and others, to create a background of blue sky and clouds. He also brought back large pieces of rectangular ivory, a size and format that had not been used in the United States. Several portraits from the two years after his return, including Eliza Izard of 1802 (private collection) and Lydia Allen of 1803 (Museum of Art, Rhode Island School of Design, Providence), were painted on sheets of ivory five inches high.

Malbone’s most celebrated style first appeared during a stay in New York from December 1803 to April 1804. He began highlighting his sitters against a pale, lightly washed and hatched background with a feigned landscape that began at the sitter’s shoulder, covering the lower third of the portrait in pale shades of turquoise and mauve (see Fig. 4). The effect was unlike anything he would have seen in London.5

Malbone appears to have met Jarvis and Wood in 1803, for his account book indicates that he knew Wood well enough by mid-1804 to have lent him twenty dollars.6 Their meeting apparently led to an offer on Malbone’s part “to impart any knowledge he possessed; and to his instructing both Jarvis and Wood, in his mode of proceeding, from the preparation of ivory to the finishing the picture, and they both became painters of miniature.”7

By the end of 1805 Malbone’s health was failing. In search of a more salubrious climate he sailed for Jamaica in November 1806, but found the island the “most wretched and miserable hole that I was ever in.”8 In January he set off for the home of his cousin Robert Mackay in Savannah, where he died of consumption on May 7, 1807, at the age of twenty-nine.

Malbone’s professional career spanned less than twelve years. Allston said of him, “As a man his disposition was amiable and generous, and wholly free from any taint of professional jealousy.”9 Such was his fame that almost three decades after his death, when Richard Morrell Staigg, a young English sign painter from Leeds (who later became a member of the National Academy of Design), immigrated to Newport, he began by copying Malbone’s works. Employing Malbone’s feigned landscape background, Staigg painted Christopher Grant Perry in 1840 (Fig. 7). His 1841 miniature portrait of the now elderly Allston (Metropolitan Museum of Art) is similar in style to Malbone’s 1801 portrait of his friend.

Anson Dickinson

An advertisement in the New Haven Connecticut Journal on May 27, 1802, announced the commencement of Anson Dickinson’s career as an artist.10 By May 1804 he was successful enough to leave for New York, where he established a studio on Broadway. In addition, he traveled through western Connecticut and New York State, painting some of his finest early works. His portrait of Royal Ralph Hinman, taken in Litchfield, Connecticut, in 1807 (Fig. 8), shows Malbone’s pronounced influence in the placement of the sitter and the use of the glowing ivory support.

Years later William Dunlap (1766–1839), who is the principal source of information on the early arts in this country, recorded that in 1811 Dickinson “was the best miniature painter in New-York,” but that “the promise of his youth has not been realized.”11 Despite Dunlap’s harsh assessment, Dickinson’s satisfied sitters included General Jacob Brown, General Peter Buell Porter, Sam Houston, Gilbert Stuart, and Washington Irving. He remained indebted to Malbone throughout his career; as late as about 1840, though working in the more fashionable rectangular format, he was still employing Malbone’s feigned landscape background (see Fig. 9).

Joseph Wood

In 1811, after arriving in New York from New London, Connecticut, the miniaturist Mary Way (1769–1833) wrote that Joseph Wood (Fig. 10) was, “from what I have heard and seen…the only painter here worth notice.”12 The son of a farmer in Clarkstown, New York, at the age of fifteen Wood ran away to New York City, where he was first apprenticed to a silversmith.13 By 1801 the twenty-three-year-old artist had married and was established as a miniaturist. In 1803 he formed an association with John Wesley Jarvis. Recounting Jarvis’s recollection of the early years of the partnership, Dunlap recorded that the two often made a hundred dollars a day taking profiles with a physiognotrace. “These were piping times,” he wrote, “and what with Jarvis’s humour, Wood’s fiddling and fluting—and the painting executed by each, they had a busy and merry time of it. But I fear ‘merry and wise,’ was never the maxim which guided either.”14 He went on to say that the two artists “indulged in the excitements, and experienced the perplexities of mysterious marriages; and it is probable that these perplexities kept both poor, and confined them to the society of young men, instead of that respectable communion with ladies, and the refined circles of the city, which Malbone enjoyed: and I have reason to think, that these mysteries and perplexities caused the dissolution of the partnership of Jarvis and Wood on no friendly terms.”

An artist of shimmering talent, Wood appropriated more from Malbone than any of the other disciples. Often the only way of distinguishing the work of the two artists is to be able to place a portrait after Malbone’s death (compare, for example, Figs. 6 and 13).

For a short period of time before he moved to Philadelphia in 1813, Wood took on the fledgling miniaturist Nathaniel Rogers (1787–1844) as an apprentice. He also gave instruction to Way, who described his technique of using a specific light source, which would influence academic New York miniatures for the next fifty years: “Wood closes the lower casement with the shutter. Of course, the light strikes with most force upon the temple or side of the forehead which projects most as the head is a little turned. Next, it falls upon the cheek bone under the eye, where a delicate shade tint begins, almost imperceptible, losing the light by degrees towards the lower part of the face” (see Fig. 11).15

When Wood died in 1830 the Washington National Intelligencer ran the headline, “Death of a Man of Genius.” And indeed he was. President James Madison, Eli Whitney, De Witt Clinton, Commodore James Biddle, Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry (Fig. 12), General Andrew Jackson, and Francis Scott Key all sat to him. But Dale T. Johnson noted that “his notoriously dissolute life was the basis for a temperance tract published in Washington in 1834.”16

John Wesley Jarvis

John Wesley Jarvis (Fig. 14) was an “engraver, sculptor, silhouettist, natural scientist, anatomist, wine-bibber extraordinary, the best ‘story teller that ever lived’ and, in his day, he enjoyed a position ‘in the foremost rank of American masters.’”17 Born in England, a great-grandnephew of the fire and brimstone founder of Methodism, John Wesley (1703–1791), Jarvis spent the first five years of his life under the great man’s protection, and probably the rest of his raucous life rebelling. Jarvis was taken to the United States at the age of five. In Philadelphia he discovered the studio of his first instructor Matthew Pratt (1734–1805) and was introduced to Gilbert Stuart (1755–1828), who made a lasting impression on him.

About 1796 or 1797 he was apprenticed to the artist and engraver Edward Savage (1761–1817). Jarvis fumed, “He was not qualified to teach me any art but that of deception. There he was a master—at drawing or painting, I was his master. Mr. David Edwin [1776–1841] arrived in America with more skill than money, and Savage engaged him to engrave for him. From Mr. Edwin I learned to draw and engrave, and we worked for the fame and profit of the great Savage.”18

After honorably working off his apprenticeship, Jarvis established himself in New York in 1802. Edwin convinced him to relinquish engraving to take up portraiture: “I was the best painter because others were worse than bad—so bad was the best,” he declared.19

Swiftly creating an unforgettable persona, Dunlap recalled that “Mr. Jarvis was fond of notoriety from almost any source, and probably thought it aided him in his profession. His dress was generally unique. His long coat, trimmed with furs like a Russian prince or potentate from the north pole, must be remembered by many; and his two enormous dogs, which accompanied him through the streets…often carried home his market basket.”20 Years later, in New Orleans, John James Audubon (1785–1851) would describe Jarvis as sporting a large boutonniere of magnolia flowers, with a young alligator nestled in them.21

Despite Jarvis’s “joking, carousing, and philandering,” his biographer Harold Dickson wrote, “behind the screen of his growing reputation for eccentricities and drollery, Jarvis labored conscientiously at his easel and let none of this stand in the way of the sound development of his artistic powers.”22 As kind as he was witty, he took in the elderly Thomas Paine in 1807, and made sure that he provided a struggling Thomas Sully enough work to feed his family.

Less directly influenced by Malbone than either Dickinson or Wood, Jarvis developed a similar but singular style for his portrait miniatures. Though occasionally employing Malbone’s early technique of silhouetting his sitter against a dark ground, Jarvis, in the majority of his portraits, showed the subject against a pale background fashioned of the thinnest watercolor washes (see Fig. 15). Way reported: “Jarvis says, in viewing a picture, the background should not be noticed—that is, never be seen or observed till it is look’d for.” Using his training as an engraver, Jarvis modeled his faces with a meticulous web of crosshatches, floating pale washes of color to build the skin tones. Jarvis’s own outsized personality was occasionally reflected in his miniatures. The haughty grandeur of his sitter in 1807 Ray Bans shown on the cover epitomizes his stylish circle. Perfectly illustrating his hide in plain sight rule about backgrounds, the sitter is placed against monochromatic shades of gray.

Jarvis did not remain a miniaturist throughout his career. With the coveted commission to paint the full-length portraits of the heroes of the War of 1812 for New York’s City Hall he became the most prominent painter in the city.

New York style, a new generation

Young Henry Inman walked into a fortuitous situation when, in 1814, he signed on as Jarvis’s apprentice. Equally fond of joking and pranks, and showing enormous promise as an artist, Inman spent a happy seven years with his master. Together they traveled from Boston to New Orleans. By the end of his service, Inman was an accomplished artist with important connections and amusing tales.

Upon striking out on his own in 1821, Inman took on Thomas Seir Cummings as his apprentice, and by 1824 they were partners, often finishing and signing works together (see Fig. 16). Dunlap recorded, however, that “Inman devoted himself almost exclusively to oil painting, leaving Cummings, in the year 1827, the best instructed miniature painter in the United States.”23

Learning by example of what not to do, this new generation of New York artists—Rogers, Inman, and Cummings—tutored by the erratic geniuses Jarvis and Wood were the first to approach art as a business.24 They had stable marriages, sturdy families, and strong work ethics. All three became founding members of the National Academy of Design. Cummings would teach miniature painting there for more than thirty years, additionally serving as professor of the arts of design at the College of the City of New York. For the next three decades, virtually every young miniaturist passing through New York in search of academic training would be touched by Cummings. In 1834 he wrote: “Works in miniature should possess the same beauty of composition, correctness of drawing, breadth of light and shade, brilliancy, truth of colour, and firmness of touch, as works executed on a larger scale” (see Fig. 17).25 Cummings, more than any other artist of his generation would influence the next generation of New York miniaturists. The look and technique that had evolved from Malbone to Dickinson, Jarvis, and Wood, then to Rogers and Inman, and subsequently to Cummings, was, by 1830, recognized as the uniquely American “National Academy” style.

1 Mona Leithiser Dearborn, Anson Dickinson, the Celebrated Miniature Painter, 1779–1852 (Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford, 1983), pp 5-6. 2 Quoted ibid., p. 5, from Reunion of the Dickinson Family at Amherst, Mass., August 8th and 9th, 1883 (Binghamton, N. Y., 1884), p. 181. 3 William Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design in the United States (1834; Dover Publications, New York, 1969), vol. 2, part 2, p. 333. 4 Ruel Pardee Tolman, The Life and Works of Edward Greene Malbone, 1777–1807 (New-York Historical Society, New York, 1958), p. 26. 5 Not only do Malbone’s miniatures not resemble those with the blue skies and clouds by Cosway and others, they are also unlike another style of miniature painting that was emerging in London in the early nineteenth century. Backed by Royal Academy president Benjamin West, the miniaturist Andrew Robertson (1777–1845) was developing a technique of employing thickly gummed paints on rectangular format ivory to create portraits that were meant to emulate oil paintings—a style that eventually brought great changes to the appearance and theory of miniature painting in London. For a thorough discussion of the early nineteenth-century upheaval in the art of portrait miniatures centered around the Royal Academy, see Katherine Coombs, The Portrait Miniature in England (V and A Publications, London, 1998), pp. 104–114. 6 Tolman, Life and Works of Edward Greene Malbone, p. 37. 7 Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design, vol.2, pp. 76–77. 8 Quoted in Tolman, Life and Works of Edward Greene Malbone, p. 53. 9 Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design, vol. 2, p. 16. 10 Quoted in Dearborn, Anson Dickinson, p. 4. 11 Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design, vol.2, p. 217. 12 Quoted in Ramsay MacMullen, Sisters of the Brush: Their Family, Art, Life and Letters 1797–1833 (PastTimes Press, New Haven, 1997), p. 25. 13 Dale T. Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection (Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1990), p. 233. 14 Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design, vol. 2, p. 77. 15 Quoted in MacMullen, Sisters of the Brush, p. 27. 16 Johnson, American Portrait Miniatures in the Manney Collection, p. 233. 17 Theodore Bolton and George C. Groce, “John Wesley Jarvis: An Account of His Life and the First Catalogue of His Work,” Art Quarterly, vol. 1 (Autumn 1938), pp. 299–321. 18 Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design, vol. 2, pp. 75–76. 19 Ibid., p. 76. 20 Ibid., p.79. 21 John J. Audubon, Delineations of American Scenery and Character (G. A. Baker and Company, New York, 1926), pp. 86–91. 22 Harold E. Dickson, John Wesley Jarvis, American Painter, 1780–1840 (New-York Historical Society, New York, 1949), p. 124. 23 Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design¸ vol. 2, p. 400. 24 Conversation with Carrie Rebora Barratt, curator of American Paintings and Sculpture, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 25 Thomas Cummings, “Practical Directions for Miniature Painting,” in Dunlap, A History of the Rise and Progress of the Arts of Design, vol. 2, p. 10.

Google the name “Elle Shushan” and you turn up a Broadway producer, an antiques dealer, and one of Cher’s former agents. In 2002 when the New Yorker ran an article about a gathering of Cher’s former associates, Elle Shushan recalls that she was at the Winter Antiques Show plying her trade as the preeminent American dealer in portrait miniatures. “People kept coming up to me saying, ‘There’s someone out there with your name,’” she says. What is funny about this is that Shushan is all of the Elle Shushans on Google—and Google doesn’t know the half of it.

The daughter of a well-connected and colorful New Orleans family, Shushan was raised in the city’s Uptown neighborhood, and is still very much of it—she enjoys serving visitors her syrupy “Café du Monde café au lait.” But after going north to college, a love for theater drew her to New York. In 1976 she joined the William Morris Agency and was sent to Los Angeles to run their theater department.

In Los Angeles she found an apartment in “one of those strange Mexican Gothic places,” she says, which suited her perfectly: “I’m creepy,” she insists, citing her love of memento mori and “little Gothic chairs.” Today, Shushan lives in Philadelphia, in an apartment hung with her palm-sized portrait miniatures. Their subjects’ candid expressions glow with a ghostly intimacy, an effect deepened in the apartment by a small mob of worn tombstones arranged in a corner.

Toward the end of her tenure in Los Angeles, in 1980, Shushan bought her first miniature after reading Prince Jack, about Jack the Ripper. She began to devour history. “I bought miniatures to cement my learning,” she says. Collecting was not new to her—as a teenager she had bought Chinese export porcelain; nor were portrait miniatures—her great uncle and cousin, Harry Latter and Shirley Schlesinger, had assembled a collection now at the New Orleans Museum of Art. And she was still in show business. Returning to New York, she worked for CBS and in 1985 mounted Boys of Winter, a play about Vietnam starring Matt Dillon and Wesley Snipes.

But in New York she had a mentor. On weekends she worked for the dealer Ed Sheppard, from whom she bought her first pieces. She sold a miniature on her own in the late 1980s, but her apprenticeship only came to an end in 1997, when she went into business for herself.

Shushan is much in demand. She spends almost as much time advising museums and other institutions as private clients. The portrait miniature market is split into two theaters, the European, with royal family trees billowing with plumage and white wigs, and American portraits, “my cross-eyed little stick figures,” as Shushan describes them, mocking European disdain for work done on this side of the Atlantic. The record price for a portrait miniature, $1.2 million, is considered an anomaly; the high end more routinely hangs in the upper five figures. One collector‘s whim can have a deep effect on prices, which inhibits speculation.

Shushan urges clients to buy a portrait miniature as she does, “prepared to spend the rest of my life with it.” In her apartment a recent arrival, a British noblewoman, smiles benignly from the mantel. “I’ll know everything about her before I sell her,” says Shushan, who is less the lady’s owner than an advocate, a friend who loves her look, and keeps an eye on her commercial prospects—in fact, very like an agent.

By Paul O’Donnell