Before photography was introduced to America in 1839, a portrait by an artist who is today called a folk painter was the only way most Americans had to preserve images of themselves and their loved ones. But folk art portraiture from the first half of the nineteenth century has been a particular challenge to study, as most portraits were not signed by the artist. Even with the rare signed examples, it is often difficult to determine from historical records which individual among several people with the same name was the artist. Scholars have struggled to connect the artist’s name and history with stylistically related portraits.

One such difficult identification has been Mary B. Tucker, who signed and dated several watercolor portraits during the early 1840s that have long been admired by collectors. However, the search for an individual with this name has proven elusive. About all that was known was that most of her distinctive large watercolor portraits were found in Massachusetts.1

In 2009, it was suggested that the artist was Meribah Tucker (1784–1853) of Douglas, Massachusetts.2 Prior to her marriage in 1816 to Chilon Tucker, a farmer in Uxbridge, Massachusetts, she appears in Douglas town records as both Meribah and Mary B. Mowry. However, there is no evidence that Meribah was an artist, and it seems unlikely that she painted the signed and dated portraits in just a few years when she would already have been past fifty-six years old. The recording of her name as Mary B. was probably just an erroneous phonetic spelling, as at no time during her married life or at her death was Meribah Tucker called Mary B. Tucker. The conjecture that she might be the artist was primarily based on the difficulty of finding a woman in Massachusetts with the correct name.

We can now present evidence that the artist was Mary Bagnall Tucker (1824–1898) and can further add that she produced portraits not only in watercolors but also in pastels, as well as oil-on-canvas landscapes. In order to understand her life and art, it is necessary to understand her family background. She was the daughter of the Reverend Thomas W. Tucker (1791–1871), a long-serving minister in the Methodist Episcopal Church, whose itinerant lifestyle shaped her childhood and teenage years. Detailed information about the family was recorded in the journal and other writings of her mother, Mary Orne Tucker (also called Polly, 1794/5–1865), published in 1872 as Itinerant Preaching in the Early Days of Methodism, by a Pioneer Preacher’s Wife.3

Methodism had its origins in England during the late 1730s when the Anglican minister John Wesley sought to reignite Christian values. In the United States, the church presented a highly charged evangelical experience that greatly altered many Americans’ religious beliefs. Salvation from sin was available to anyone with enough enthusiastic repentance, faith, and deep conviction. Church services were filled with religious fervor, the singing of devotional hymns, emotional testimonials of people’s religious conversion, and forceful sermons.4

Reverend Tucker was an itinerant circuit rider for the church. Methodist ministers were assigned to a specific town and given a defined route to travel in the surrounding area, preaching to widely dispersed congregations and other groups. Circuit routes often traversed difficult terrain and required anywhere from two to six weeks to complete. The Methodist Church at this time did not require its ministers to hold advanced college degrees, unlike other religious groups. It was open to any man with a strong enough commitment to preach about how he had been transformed by the words of the Bible.

To capitalize on their evangelical spirit, Methodist ministers were reassigned to a new location every year or two. They were paid a very small salary, and with the cost of almost constant traveling, their expenses were seldom covered. Appreciative church members provided food, clothing, and even housing as few parsonages had been constructed. Ministers who were married and also had children to support faced particularly difficult financial and family challenges.

Mary Orne Tucker’s journal describes her marriage to a “penniless Methodist preacher” and her efforts “by the fruits of her pen and pencil, and by private tuition, to add to the allowance of her husband, often scanty.” At several locations, she established literary associations and “often contributed . . . to the columns of newspapers” with commentary based on biblical passages. She was “a woman of more than ordinary intellectual power; quite inclined to literary pursuits . . . a faithful companion with her husband, while he was able to endure the labors of an itinerant life.”5 Her journal describes that she sketched and painted with watercolors, and to entice the local children to attend her Sunday religious school, she promised that if they came she “would make each of them a present of a painting in water colors.”6

Reverend Tucker and his family were assigned to New London, Connecticut, when Mary Bagnell Tucker was born on January 8, 1824, the youngest of the three children in the family who survived to adulthood. The Tuckers valued education and, with appointments to the Massachusetts towns of Wilbraham in 1832 and Westfield in 1833, sent their children to the academy in each town. During a subsequent assignment in Lunenburg, Massachusetts, in 1834, Mary Orne Tucker and elder daughter Hannah, who “was quite proficient in the solid as well as the ornamental branches of learning,” together “commenced a young ladies’ school in our house. We soon had nearly forty pupils; and the income from this source furnished the family with many articles of comfort.”

The two older Tucker children left home in 1836 and only Mary B. continued to live and travel with her parents. Reverend Tucker was reassigned and the family moved to eight different locations in Massachusetts between 1837 and 1847.7 During 1840 the family rented half a tenement in Natick, Massachusetts, and, when typhus spread through the community, “our daughter [Mary B.] was prostrated with it.” Because of their frequent moves, the family was often not included in censuses and town historical records.

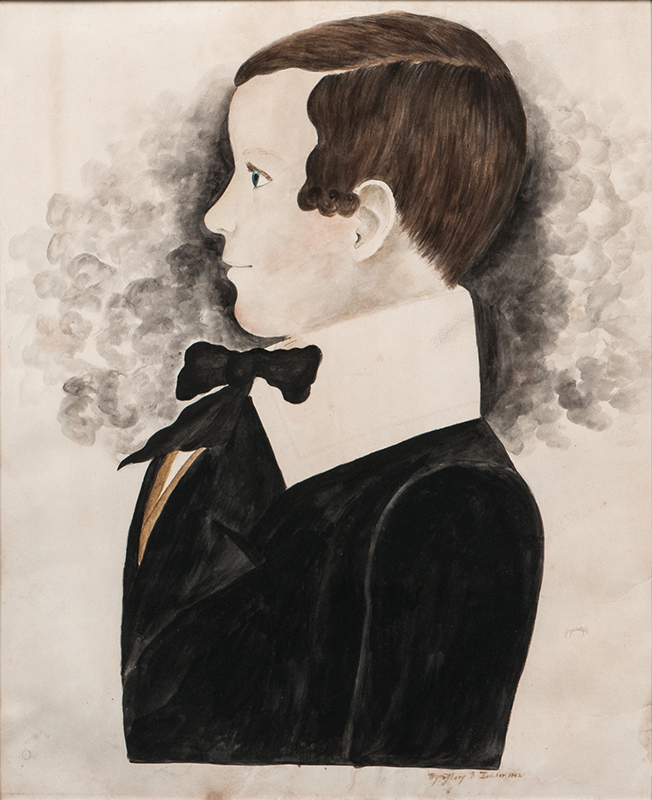

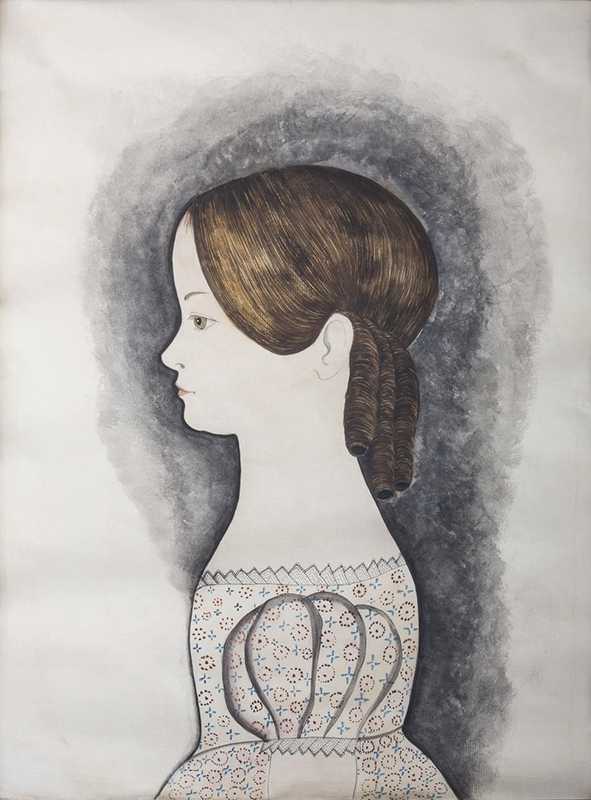

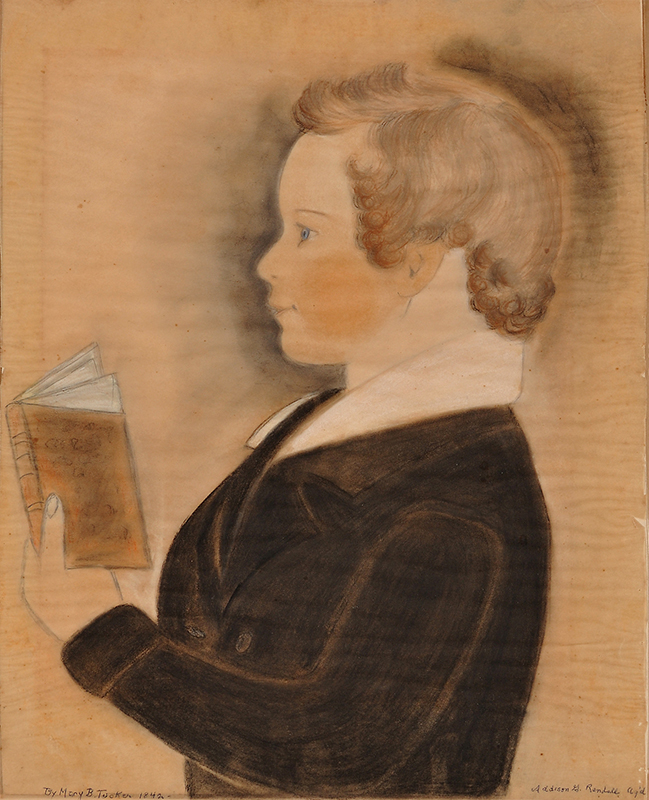

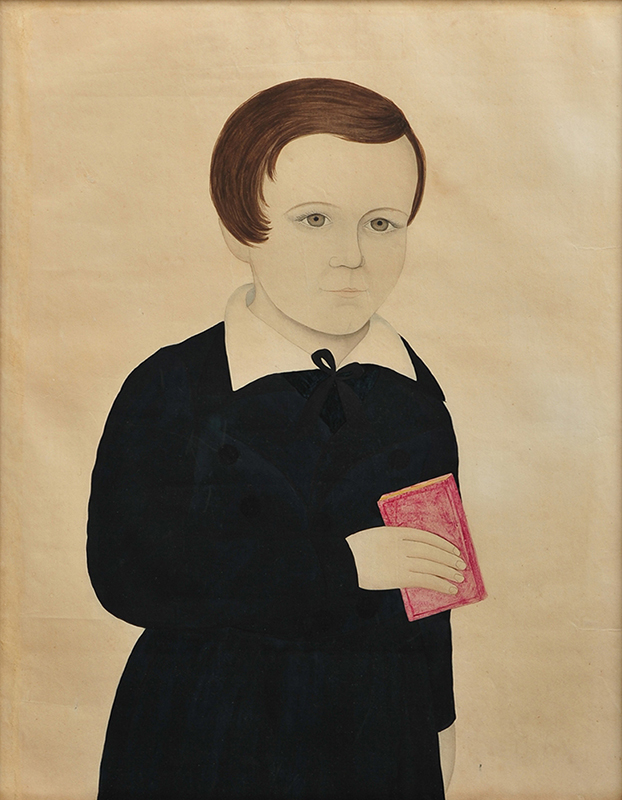

The earliest Mary B. Tucker signed portrait is dated 1840, so she began painting her distinctive large watercolors and pastels at age sixteen. During the 1840s, few artists were using watercolors to produce large-format likenesses, but Tucker embraced the colorful medium, which allowed a new level of freedom and fluidity, to produce portraits on sheets of paper that ranged in size up to twenty-six-by-twenty-one inches. She developed two distinctive portrait styles: profiles and more painterly full-face depictions. From the inscribed dates, the profiles were her earliest style. These bust-length images, almost like plaster casts recorded on paper, are strikingly graphic and modern looking, with some approaching abstraction (Figs. 2–4). The unpainted paper is an integral part of the image, serving as both the background and, when outlined, a component of the sitter’s likeness, demonstrating Tucker’s economy of style. A black penumbra separates the face and neck from the background, focusing the viewer’s interest. In the 1842 portrait of a boy holding an orange there is a move away from the dark tones that often dominated the earlier works to heightened coloration, with the rich blue-green dress, yellow hair, and red pillow (Fig. 6).

In the likeness of a baby with a teething ring in Figure 7, from 1843, Tucker replaces the profile bust with a full figure set in one of the few examples of her work that provides a sense of place. The baby lacks color compared to the surrounding floral carpet and background wall, while the unusual shape of the skull also adds interest to the portrait. Altogether, the painting shows that Tucker was continuing to experiment with ways to present a sitter’s image.

Portraits from 1844 and later are full face, with the paper usually fully covered in watercolor, but with exceptions (Figs. 8a, 8b). Several of Tucker’s portraits depict children, including pairs that convey the love between siblings (Fig. 1). In the full-face portraits, the sitters are presented in a two-thirds body view. Adults are often seated, and the backgrounds often vary in intensity due to the wide fluid brushstrokes. The eyes are always wide open and painted without eyelashes, creating a pronounced stare and a vitality that seems eager to make contact with the observer. These paintings embody the graphic energy of American folk portraits from the first half of the nineteenth century, which focused on direct communication between sitter and viewer.

No advertisements offering Tucker’s services as a portrait painter have been located despite an extensive search of period newspapers from throughout New England. Her subjects were probably people she knew, and the sitter’s name is recorded on only one signed pastel (Fig. 5). With her family’s life centered on religion, many of her sitters may have been acquaintances with similar religious views. In several portraits, the subject holds a piece of paper, a Bible, or other book on which Tucker, in her distinctive handwriting, meticulously recorded quotations that affirm the sitter’s religious devotion.8 In a pair of portraits of a husband and wife signed and dated 1844, for example, the man holds an open Bible, on the pages of which the viewer can read portions of Acts 17:30, Matthew 3:9, and Matthew 5:6–16 (Fig. 9).9 Similarly, in the three-portrait Evangelical Family group, the father (Fig. 10) holds a sheet of paper containing portions of a sermon written by George Washington Montgomery (1810–1898), a prominent Universalist minister, that was published in the Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate in March 1846.10 The Tucker family may have known Montgomery, or, at the very least, would have been familiar with his influential book, Illustrations of the Law of Kindness, first published in 1840/1.11 The mother in this family group is seated at a table with a book whose size implies that it is a Bible (Fig. 12). In his portrait, the son holds a book showing several numbered pages with portions of text, enough of which can be read to ascertain that the book is a collection of writings by Anna Laetitia Barbauld, an Englishwoman of letters whose work often has a heavy moral tone (Fig. 11).12

Mary Orne Tucker’s book confirms that her daughter Mary continued to produce portraits through 1846. That year, both women were allowed, for the first time, to attend the annual Methodist Meeting in Boston as spectators at the debates. “We had recourse to our pencils, and attempted to sketch a few heads of notable preachers. My daughter succeeded in making . . . Bishop Waugh. He has a massive head, whitened by time, and a fine expressive countenance.” In addition to large portraits in watercolors and pastel, Mary B. Tucker was also producing oil on canvas landscapes.13

Mary B. Tucker lived with her parents until November 24, 1847, when at the age of twenty-three, she married Dr. David Sylvester Fogg (1821–1893), a graduate of Dartmouth’s medical school with a practice in South Dedham, Massachusetts. The Foggs remained in South Dedham (called Norwood after 1872) for the rest of their lives, raising eight children, six of whom survived to adulthood. While no portraits in watercolor or pastel have been located that are dated after her marriage, she continued painting landscapes in oil on canvas. Several of her views of early Norwood are today preserved in the Norwood Historical Society.14 She died in Norwood in 1898 at age seventy-four with the cause of death listed as cerebral paralysis.15

Painted some 175 years ago, Mary B. Tucker’s distinctive watercolor portraits continue to be appreciated today for their surprising vitality and appeal. It is highly satisfying to be able to connect them to the artist and the details of her life’s story.16

1 Colleen Cowles Heslip and Charlotte Emans Moore, A Window Into Collecting American Folk Art: The Edward Duff Balken Collection at Princeton (Princeton, NJ: Art Museum, Princeton University, 1999), pp. 136–137. 2 Arthur B. Kern, “Mary B. Tucker, Elusive Portrait Painter,” Antiques and Fine Art, Autumn/Winter 2009, pp. 146–151. The authors are in possession of the late Arthur B. and Sybil B. Kern’s folk art research notes, including those on Mary B. Tucker. We present in this article only signed Tucker portraits or ones that are directly comparable to signed examples. 3 All quotes and details about the Tucker family are from Mary Orne Tucker, Itinerant Preaching in the Early Days of Methodism, by a Pioneer Preacher’s Wife (Boston: B. B. Russell, 1872), unless otherwise noted. The book, which is still referenced today for its detailed description of an early Methodist minister and his family, was edited by the author’s son, Thomas, who also had it published. The author should not be confused with a different, earlier Mary/Maria Orne Tucker (1775–1806), whose diary is in the Peabody-Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. 4 The wave of evangelical religious zeal that spread across America is referred to as the Second Great Awakening. See John H. Wigger, Taking Heaven by Storm: Methodism and the Rise of Popular Christianity in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). 5 Minutes of the Sixty-ninth Session of the New England Annual Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, Held at East Boston, Mass., March 25, 1868 (Boston: James P. Magee, 1868), p. 32. 6 To date, the authors have been unable to locate any art produced by Mary Orne Tucker. 7 Portraits by Mary B. Tucker have been identified from several towns where Mary Orne Tucker’s journal records Reverend Tucker was assigned. The family moved with each new assignment. According to Mary Orne Tucker’s journal, in 1839–1840 he was assigned to Holliston and in 1840 half time in Framingham and half time divided between Natick and Needham with the family living in Natick. In 1842–1843, he was assigned to Sudbury; in 1843 to New England Village, which was the northern portion of Grafton; 1844–1845 to Watertown; and in 1846–1847 to Dorchester Lower Mills. His final ministry was in Medford in 1847, and his career ended in 1848. 8 The detailed text included in several portraits is written with the same lettering as seen in Mary B. Tucker’s signature. 9 Stacy Hollander, American Radiance: The Ralph Esmerian Gift to the American Folk Art Museum (New York: American Folk Art Museum and Harry N. Abrams, 2001), p. 402. The portraits were sold at Sotheby’s on January 25, 2014, lot 607. 10 George Washington Montgomery, “Topics for Reflection,” Evangelical Magazine and Gospel Advocate, vol. 17, no. 11 (March 13, 1846), p. 85. 11 The book was reprinted numerous times and by several publishers. 12 Mrs. S. J. Hale, Things by Their Right Names, and Other Stories, Fables, and Moral Pieces, in Prose and Verse, Selected and Arranged From the Writings of Mrs. Barbauld . . . (Boston: Marsh, Capen, Lyon, and Webb, 1840). A Methodist family at this time would have been aware of the hymns included in their church services and publications by Mrs. Barbauld’s father, who was a leading minister in England, and her brother, both named John Aikin. 13 For an example, Snow Landscape with People Riding in Sleigh, oil on canvas, 24 by 36 inches, signed by Mary B. Tucker, see Blackwood/March Fine Art and Antique Auctioneers, Essex, Massachusetts, November 17, 2012, lot 159. 14 Two oil-on-canvas landscapes of Norwood by Mary Tucker Fogg, in the Norwood Historical Society collection, are illustrated in Patricia J. Fanning, Norwood: A History (Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2002), pp. 11–12. 15 Massachusetts Vital Records, 1840–1911, available online at sec.state.ma.us/

vitalrecordssearch. 16 We would particularly like to thank Richard Miller for sharing his insights on Mary B. Tucker.

MICHAEL R. PAYNE and SUZANNE RUDNICK PAYNE are collectors and members of the American Folk Art Society. This is the seventeenth article they have published about early American folk portrait painters.