“Oh dearly I love painting, how cheerfully could I give up almost all other enjoyments for the delightful privilege of painting what I liked as I liked it.”1 Written by a woman artist in 1843, these thoughts reflect the philosophy of romanticism and its attitude toward artistic creation. From the end of the eighteenth century and during the first half of the nineteenth, romanticism prompted an age of introspection in America, as it asked individuals to rebel against the confinements of tradition and emphasized freedom of expression, imagination, and the passions.2

A romantic artist felt a higher calling that required an independent spirit, open to new possibilities for artistic creation. Paintings were not just a mimetic record of reality but a visual language that excited the emotions and conveyed the artist’s creative force. A portrait represented a communion between the artist and the sitter’s inner life. The American painter Washington Allston wrote, “trust to your own genius, listen to the voice within you . . . she will enable you to translate her language to the world, and this it is which forms the only real merit in any work of art.”3

One of the most prominent expressions of romanticism in American art was found in the landscape paintings of the Hudson River school revealing the wonders of nature. At the same time, romanticism also greatly influenced American folk portrait painters. This was particularly true of the artists who worked in watercolor on paper. The expressive ability of the medium to re-create the sensations of light, color, and fluidity allowed the artist’s imaginative feelings to be captured with spontaneity and directness.

Among the most acclaimed of these portrait painters were an unusual wife and husband team, Ruth Whittier Shute and Samuel Addison Shute.4 Over the years, considerable confusion has been created as portraits in multiple painting styles have been attributed to the Shutes. Today, more than forty signed examples can be studied, allowing for a clearer view of their oeuvre.5

Ruth was born on October 28, 1802, in Dover, New Hampshire, the ninth of Obadiah and Sarah Austin Whittier’s ten children. Her father built and operated water-powered textile mills on the Cocheco River in Dover, and, when he died in 1814, Ruth’s eldest brother, Moses, continued the family’s business. They were Quakers and in 1817, when Ruth was fourteen years old, her widowed mother Sarah advertised in two Portsmouth, New Hampshire, newspapers her proposal to establish a Young Ladies Academy offering instruction in “Reading, Writing, English Grammar, Arithmetic, Geography, and Rhetoric” as well as “drawing, painting on paper, wood, silk and velvet.”6 Growing up in this prosperous and education oriented family, Ruth learned artistic skills that she developed into a profession, wrote poems enhanced with fancy penmanship that sometimes accompanied her portraits, and taught school. She was also the cousin of John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–1892), a celebrated poet and an important leader in the abolitionist movement.

Samuel was born in Essex County, Massachusetts, on September 24, 1803, one of Aaron and Betsey Poore Shute’s two children.7 He attended Governor Dummer Academy (now the Governor’s Academy) in Byfield, Massachusetts, and then medical school at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. This was a prestigious medical education compared to most doctors at the time, who were taught through a three-year apprenticeship with a local physician. Additionally, as there were no laws preventing anyone from calling himself a doctor, some practitioners just learned a little folk medicine and treated patients. Diaries written by physicians in New England show that medicine was not a particularly lucrative career and that many payments came in the form of farm produce. A house call meant slow travel by horseback, but only brought a fee of thirty-five to seventy-five cents. People were also skeptical of the common medical treatments such as bloodletting, purging, blistering, and various tonics that produced few positive results.8

During 1827 Samuel practiced medicine in Weare, New Hampshire, and was considered to be such a distinguished citizen that he was asked to deliver the Fourth of July speech in East Weare. On October 16, 1827, he and Ruth were married in Somersworth, New Hampshire, the town in which her mother was born and raised. Samuel was also a Mason and during April 1828 was present at the meeting to organize Weare’s Masonic Lodge. However, during the 1820s, the small town of Weare had ten physicians, an oversupply that must have made continued employment difficult.9 Soon after they were married, Ruth and Samuel became itinerants who offered a combination of medicine and portrait painting as they traveled in New England and New York.10

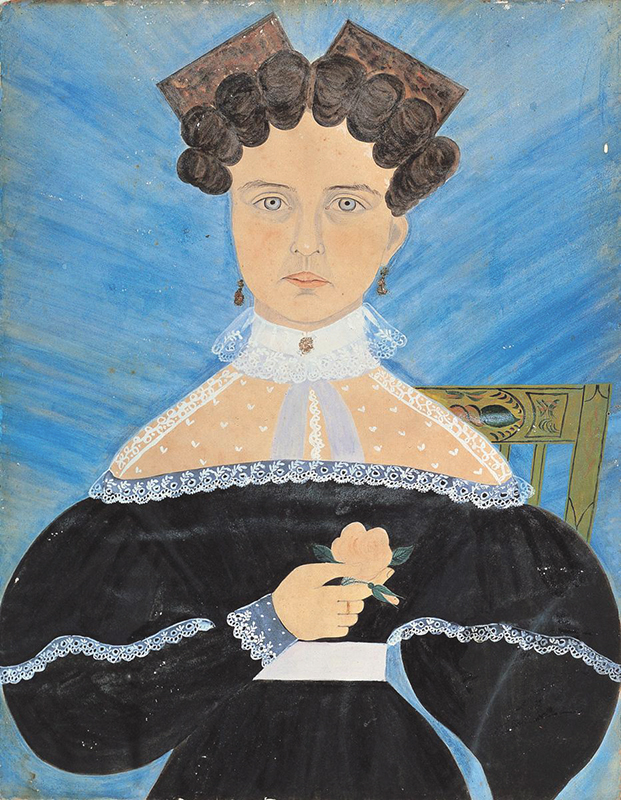

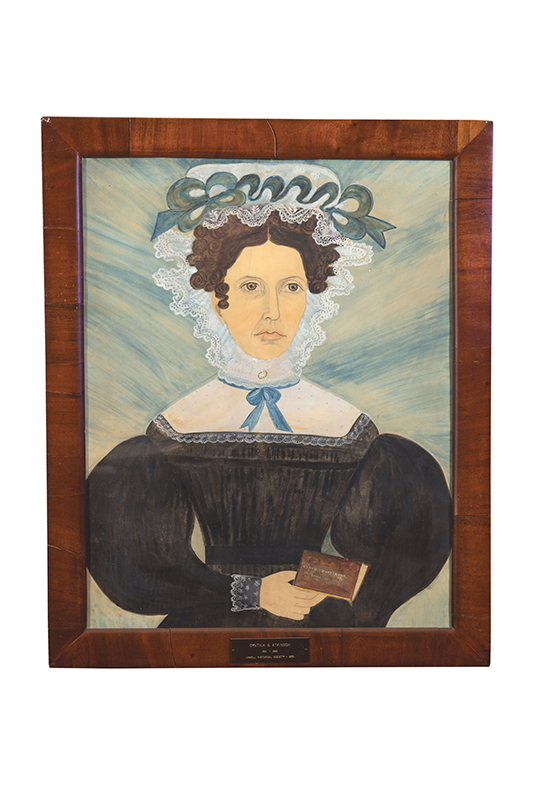

The Shutes painted dramatic large watercolor portraits that have an appealing directness of expression with their strength of design, clarity, and use of color, along with a charming artistic naiveté (Figs. 1–4). Little effort has been made to create a three-dimensional image. A flood of light falls directly on the sitter without producing shadows. Amid a vocabulary of minimal design elements, the unpainted paper forms an integral part of the image, serving as the flesh tones, while the facial features are simple sketches made with a combination of pencil and watercolor. Deeply saturated colors and animated brushwork often invigorate the sharply focused image. The sitter appears to have been painted as a series of interlocking components, often filled with broad areas of color. In many portraits, a rigid full-frontal image, flush with the picture plane, creates a direct confrontation with the viewer, who finds the almond-shaped eyes directly staring back. In other examples, the sitter looks off to the side, almost avoiding the viewer.

The portraits’ backgrounds are often filled with undulating washes or thick, slashing brushstrokes that provide no details or sense of place and remove the sitter from any context. These ambiguous, energized backgrounds and the contrasting flatness of the sitter combine to give the impression that the image is an illusion.

The women are dressed in the luxurious leg-of-mutton- sleeved dresses illustrated in lady’s fashion publications in the United States and England during the late 1820s and 1830s, but with a pronounced exuberance.11 The portraits show an oversized fullness of the dress at the arms and a tightly cinched, belted waist that together give an hourglass-shaped abstraction to the torso. Intricate lace and embroidered frills have often been patiently added. The women’s shoulders have an elegant, if impossibly long, slope. Hands, sometimes delicately tiny, are shown off in front of the sitter. Hair is stylized into rolls simulating fashionable curls and is held in place with tortoiseshell combs or covered with an elaborate bonnet. Scarves and rings appear frequently, and appliquéd gold or silver foil and metallic paint often embellish the sitter’s jewelry.

The women’s bodies have an exaggerated triangular shape that sometimes overflows the sides of the painting and leads the viewer’s eye toward the face. But the simple, monochromatic facial features on the unpainted paper recede somewhat, de-emphasizing what should be the central focus of the portrait. The dominant features of the images are instead the exaggerated dress, material finery, and idealized body contour. The Shutes’ watercolor portraits of men also show quite handsome sitters dressed in the latest fashionable clothing.

The earliest dated watercolor portraits were painted during November 1828 in the textile mill town of Lowell, Massachusetts, with the majority depicting young female mill employees. The Lowell mills, opened in 1823, were the first planned factory town in the United States.12 The mill owners had a paternalistic attitude toward the unmarried women employed from the surrounding countryside and ordered them to live in company boarding- houses overseen by a chaperoning matron. Unusually, the Shutes were allowed to live in one of the boardinghouses for unmarried women, perhaps with Samuel employed as a physician.13

The weekly wages at the mill averaged about $3.25, while the boardinghouse cost $1.25. This represented a good income at a time when there were a limited number of paid occupations available to women. Mill employment meant thirteen-hour workdays amid the roar of the factory’s machinery. For these young women, however, it brought economic independence and entrance into a new shared community, where they lived and worked together. For most of them, it was the first time they had their own income. While some used their wages to help support the family back home, it was still their money to spend or save as they wished.

Industrial development in America slowly brought about changes in society and the role of women. The letters and diaries of the women employed at the mills allow us to better understand how economic participation affected women’s self-assertion, dignity, and voice, both in their personal empowerment and in communities of workers. In 1828, solidarity was demonstrated when the women employees at a New Hampshire textile mill staged a labor strike protesting their working conditions.

The Shutes’ portraits were a visual reflection of changes in the self-perception of the mill employees. Within the highly personal object that a portrait represents, instead of displaying what was seen in a mirror, the sitter’s identity was elevated into a handsome image with the latest fashionable dress, jewelry, and glamorized body shape. Although these women were generally from rural and often poor farm families, economic independence and a working life meant that they were on a path to material and social success. Probably none of these women owned any such finery nor had the physique and feminine allure depicted in the portraits. The sitter’s family may not have even recognized the transformed person who had been painted. Perhaps to assuage any doubt, in several portraits the sitter holds a letter or book with her name on it.

The images were illusions, a blend of the artist’s creative invention and the sitter’s self-fashioning that embodied her aspirations for continued prosperity and self-improvement. They were a reflection of the romantic philosophy of striving for personal independence, gentility, and refinement.

Several pairs of husband-and-wife watercolor portraits are also known, mostly of couples who were associated with the textile mills (Figs. 6a, 6b). The Shutes’ watercolor portraits of children were also distinctive (Fig. 7). Many of them are set outdoors and depict a monumental child seemingly surveying the world, a romantic Wordsworthian vision of innocence communing with nature.

Life was not easy for the Shutes during these years. In 1829 Bimsley Perkins, owner of an inn in Hopkinton, New Hampshire, sued “Samuel A. Shute of Weare . . . Physician” for non-payment of $15.42 plus added damages for a total of $20.24. The court issued an arrest warrant “to the Sheriff of any County in this State” and ordered that Samuel be detained in “Gaol until he pay the full sums.”14 Non-payment of debts was a serious crime at the time and people who were unable to repay even small sums were sometimes incarcerated for years. Samuel apparently quickly settled this dispute as two daughters were soon born in Concord: Adelaide in 1829, an invalid who would always remain under the care of her mother, and Maria who died in 1831 at the age of nine days.15

During 1832, while again painting in Lowell and in several small towns in New Hampshire and Massachusetts, the Shutes inscribed a few watercolor portraits “Drawn by R.W. Shute and Painted by S.A. Shute” or “Painted by R.W. and S.A. Shute” on the reverse (Figs. 8, 9). This confirms their collaboration, with Ruth first using pencil to sketch out the composition and adding the facial features. It is not known whether Samuel had any formal art training, though his work as a physician included the preparation of drugs and extracts that would have made him familiar with the techniques to prepare the semi-transparent watercolors and opaque gouaches that were used in the portraits. 16

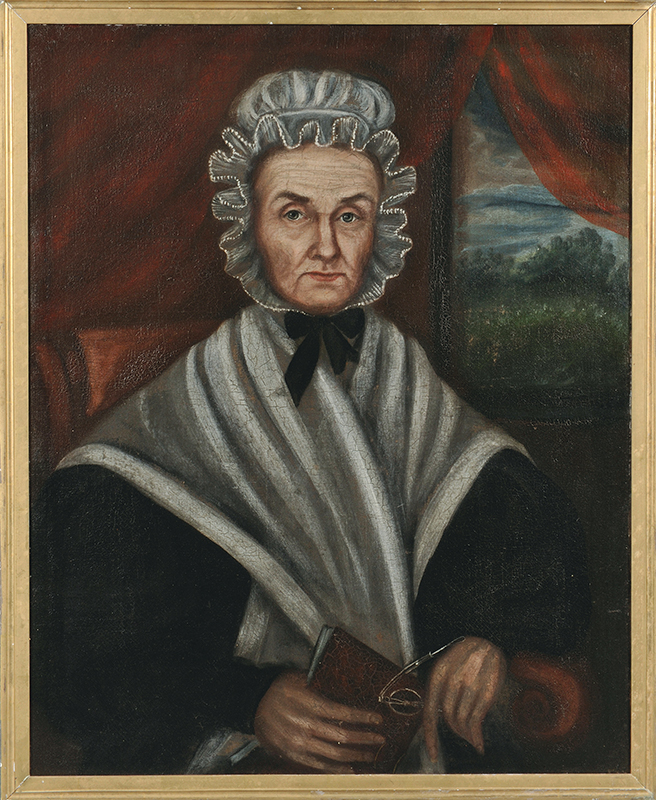

In early 1833, after approximately six years of painting watercolors, the Shutes transitioned to oil-on-canvas portraits that were produced using a similar composition and color palette to the watercolors (Figs. 11a, 11b). They began traveling over a wider area searching for commissions and started advertising in newspapers when they arrived in a new town. In February and March 1833, in Peterborough, New Hampshire, oil-on-canvas portraits were inscribed with both their names and sequentially numbered, showing that eighteen commissions were completed in thirty-one days. The oil portraits were also occasionally painted on wood panels. On April 15, 1833, they advertised in the New Hampshire Argus and Spectator in Newport, New Hampshire, that they painted inexpensive portraits affordable to their patrons. “MR. AND MRS. SHUTE Would inform the Ladies and Gentleman of Newport, N.H. that they have taken a room at Nettleton’s Hotel, where they will remain for a short time. . . Prices will be regulated, according to the size of the portrait. CALL AND EXAMINE THE PAINTINGS Price from 5 to 10 dollars.”

Ruth and Samuel’s collaboration appears to have ended about September 1833, after which the oil portraits were signed solely by Ruth. This may have been because Samuel became ill, or because he had an increasingly busy medical practice. Ruth’s portraits working alone show a strikingly different style, as seen in the signed paintings of Mr. and Mrs. Forehand from November and December 1833 (Figs. 12a, 12b).

In 1834 the Shutes moved to Champlain, New York, about forty-three miles south of Montreal, Canada. William Shute, Samuel’s deceased uncle, had been an early settler of this town and several of William’s children were living in the area.17 While painting portraits in nearby towns such as Plattsburgh, New York, and Saint Albans, Vermont, Ruth adopted a more three-dimensional painting style. Her newspaper advertisement in the Plattsburgh Republican on May 24, 1834, stated: “All who may employ her may rest assured that a correct LIKENESS of the original will be obtained. Ladies and Gentleman are requested to call and examine the paintings. Prices from $5.00 to $10.00 Miniatures from $5.00 to $8.00.” An editorial in this newspaper described Ruth’s “transferring the ‘human face divine’ to canvas. Those who wish to ‘see themselves as others see them’ will do well to improve the opportunity offered by the stay of Mrs. Shute in our village.” She had a paper label printed reading, “PAINTED by Mrs. R.W. Shute- 1835,” which was glued to the back of the portraits, suggesting that she was quite successful in acquiring sitters.

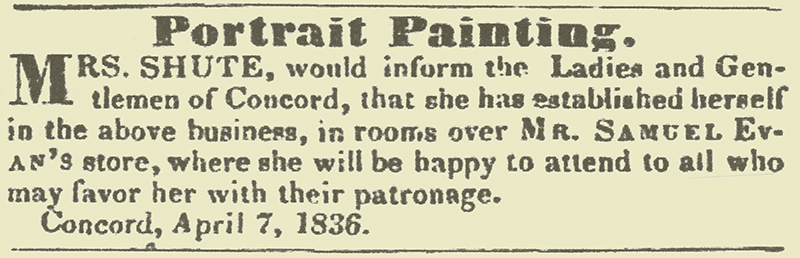

Samuel died of unknown causes on January 30, 1836, in Champlain at the age of thirty-two. He was buried in Concord, New Hampshire, where his parents were living and all of his family would be interred. A large “M.D.” was prominently chiseled on his gravestone, reflecting the family’s pride in his profession. Ruth continued as an itinerant artist for the next four years. She advertised during April 1836 in the New Hampshire Patriot of Concord that “she will be happy to attend to all who may favor her with their patronage” (Fig. 14) and during March 1838 in Amherst, New Hampshire.

In Concord on March 25, 1840, Ruth married Alpha Tarbell (1802–1868), a schoolteacher from Moriah, New York. The American economy greatly suffered at this time with the Panic of 1837, perhaps the deepest depression in United States history, which continued until about 1843. Soon after their marriage, Ruth and Alpha, along with her invalid daughter Adelaide, left New England and moved to a farm in Middletown, Kentucky. Two daughters were born in the 1840s, but life in Kentucky must also have been challenging. The 1850 Federal census found one Tarbell daughter and Adelaide Shute living with Samuel’s parents in Concord, New Hampshire. The 1860 census recorded that the family was again living together in Middletown with Alpha Tarbell described as a cattle trader.

Ruth’s painting style continued to evolve and her later portraits, which she signed as Mrs. R. W. Tarbell, are primarily of children and are noted for their diffuse contours and a dark tonality (Fig. 15).18 She died on September 26, 1882, and a history of Middletown remembers her as “a talented artist and musician, and a portrait painter of considerable note.”19 Today, a row of three gravestones stands in the Middletown Historical Cemetery commemorating Addie [Adelaide] Shute, Alpha Tarbell, and Ruth Tarbell, with Ruth’s stone reading “Thou art gone but not forgotten.”

1 Betsey Way Champlain, quoted in Ramsay MacMullin, Sisters of the Brush: Their Family, Art, Life, and Letters 1797–1833 (New Haven, CT: PastTimes Press, 1997), p. 469. 2 Colin Campbell, The Romantic Ethic and The Spirit of Modern Consumerism (Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1987); Isaiah Berlin, The Roots of Romanticism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999); and David Blayney Brown, Romanticism (New York: Phaidon, 2001). 3 Quoted in Barbara Novak, American Painting of the Nineteenth Century: Realism, Idealism, and the American Experience (New York: Harper and Row, 1979), p. 291. 4 We gratefully acknowledge the information about the Shutes described in Helen Kellogg, “Found: Two Lost American Painters,” Antiques World, vol. 1, no. 2 (December 1978), pp. 37–47. Also Helen Kellogg, “Ruth W. and Samuel A. Shute,” in American Folk Painters of Three Centuries, ed. Jean Lipman and Tom Armstrong (New York: Hudson Hills, 1980), pp. 164–170; and Helen and Steven Kellogg, “Samuel Addison Shute (1803–1836) and Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–1882),” in American Radiance: The Ralph Esmerian Gift to the American Folk Art Museum, ed. Stacy Hollander (New York: American Folk Art Museum and Harry N. Abrams, 2001), pp. 387–391. 5 Watercolor portraits with the sitter holding an envelope with their name and address are considered to be signed because the distinct handwriting is the same as in Ruth’s signed documents. Family groups are considered to be signed if one portrait is inscribed. 6 New-Hampshire Gazette, March 11, 1817, and the Portsmouth Oracle, March 13, 1817. Examination of women named Sarah Whittier in New Hampshire confirms that this advertisement was by Ruth’s mother. The school may not have opened, as no additional information has been located. Penmanship was considered to be an indicator of one’s education and Ruth’s handwriting is considerably more elegant and refined with fancy flourishes than her husband Samuel’s. 7 Samuel’s birth was recorded in both Rowley and Georgetown, Massachusetts, which was a portion of Rowley until 1838, while family history states that the children were born in Byfield. All these locations are within Essex County. 8 Barnes Riznik, “The Professional Lives of Early Nineteenth-Century New England Doctors,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, vol. 19, no. 1 (1964), pp. 1–16. 9 William Little, History of Weare, New Hampshire 1735–1888 (Lowell, MA: published by the town, printed by S. W. Huse, 1888), pp. 419, 603, 631. 10 Several American folk painters combined medicine and portrait painting, including Samuel Broadbent, Jacob Maentel, Rufus Hathaway, and Elias V. Coe. 11 Lynne Zacek Bassett, Gothic to Goth: Romantic Era Fashion and Its Legacy (Hartford, CT: Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, 2016), pp. 16–45. The Shutes’ portraits have been compared to the American and London fashion publications available at the time. 12 Thomas Dublin, Women at Work (New York: Columbia University Press, 1979); and Nancy F. Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1977). 13 Samuel wrote their boardinghouse address in his copy of the Lowell city directory, see Kellogg and Kellogg, “Samuel Addison Shute (1803–1836) and Ruth Whittier Shute (1803–1882),” p. 388. 14 The lawsuit is documented in item 2010.53, Hopkinton Historical Society, New Hampshire. 15 The record of a third daughter, Adaline born in 1836, is suspect. She and Adelaide had the same middle name, Montgomery, and there is no further information about her. 16 Based on similar stylistic features, several watercolor portraits have been suggested to represent either Ruth or Samuel painting independently. These attributions may be substantiated in the future if signed examples are located. 17 Samuel was apparently very close to his paternal uncle William and has been incorrectly recorded as William’s son. This suggests why Ruth and Samuel moved to Champlain. 18 Additional portraits are in the Historic Middletown Museum, Middletown, Kentucky. 19 Edith Louise Wood, Middletown’s Days and Deeds: The Story of 150 Years of Living in an Old Kentucky Town (Anchorage, KY: n.p., 1946), p. 112.

SUZANNE RUDNICK PAYNE and MICHAEL R. PAYNE are collectors and members of the American Folk Art Society. This is the twentieth article they have published about early American folk portrait painters.

This article is dedicated to Helen Kellogg (1930–2019). We will always remember the twinkle in her eyes when she recalled her discoveries about Ruth and Samuel Shute.