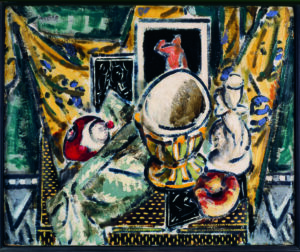

Fig. 1. Still Life with Doily by Alfred Henry Maurer (1868– 1932), c. 1930. Oil on hardboard, 17 7/8 by 21 1/2 inches. Phillips Collection, Washington, DC.

Alfred Maurer’s cubist still lifes

Alfred Maurer was at the forefront of aesthetic developments throughout his prodigious thirty-five-year career. He came to international renown in the late 1890s as an artist of ambitious Whistlerian and realist paintings, but after the turn of the century he embraced the more progressive movements upending the art world. By 1906 Maurer was creating and exhibiting radical canvases on both sides of the Atlantic. He experimented with different modernist subjects and styles over the years, yet the most sophisticated and creative are arguably the cubist compositions he produced in the late 1920s and early ’30s. These paintings masterfully juggle artifice and reality and negotiate the space between intuition and imagination. They usher the viewer out of the realm of reason into a place where all seems possible.

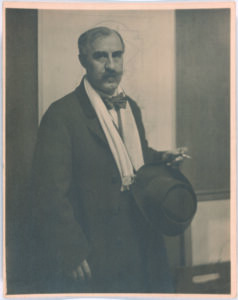

Fig. 2. Alfred Henry Maurer by Alfred Stieglitz (1864–1946), 1915 (printed later). Gelatin silver print, 9 5/8 by 7 5/8 inches. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

The first half of Maurer’s mature career was spent living and working in and around Paris from 1897 to 1914. He ascended in the ranks of the avant-garde and emerged as an early and important advocate for modernism back in America. Described by contemporary critics as having “played the historic role of the first American artist to go fauve,”1 Maurer showed his new compositions in 1909 at 291, Alfred Stieglitz’s legendary New York gallery. Noted writer Paul Rosenfeld reflected on the impact of this exhibition in 1932, stating that the Maurer show “fell like a meteorite into the local art world of artists and patrons.”2

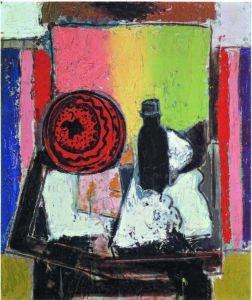

Once resettled back in New York in 1914, Maurer continued to integrate and expand on the lessons he learned abroad with increasingly adventuresome paintings. From this time until his death in 1932, he devoted significant efforts to working in a cubist syntax. Maurer adopted the language of cubism in the 1920s during an isolationist period in America, when artists were strongly encouraged to reject European artistic sources, cubism key among them. Unswayed by this and eager to define cubism in his own terms, he dove obsessively into the core of this aesthetic. Maurer manipulated, juxtaposed, and fragmented line, mass, void, and color to reimagine the concrete appearance of objects in space. In Still Life with Doily (Fig. 1) and Still Life with Croissant (Fig. 3) he used paint with a new kind of primacy, empowering it as a vital and an integral component of the composition, as important as everything pictured. Maurer’s still lifes offer vignettes where familiar objects and spaces can be seen through a new lens. The artist’s wry wit is embedded in the layers of these works. Their compositions reveal an unadulterated delight in the art of contradiction, in which reality and fiction are reimagined, as is the balance between truth and order.

Fig. 3. Still Life with Croissant by Maurer, c. 1930. Oil on board, 18 1/2 by 21 1/2 inches. Private collection.

Cubist works of the 1920s and early ’30s stoked art world fires, fueling rage among strong-minded, conservative critics. Margaret Breuning and Thomas Craven, for instance, crusaded against cubism, pronouncing it spiritually bereft and deeming it an artistic cul-de-sac.3 Maurer was undeterred by such pronouncements as were fellow American modernists, including Stuart Davis, John Graham, and Arshile Gorky (the three of whom formed a close artistic alliance). While the American artist Max Weber had been one of the leading early and important advocates for cubism in the teens, these artists piloted a second wave of cubism in America, refusing to succumb to provincial attitudes that would oust European-born modernism. Maurer was among the insightful few who recognized that modern American art could be rooted in a European tradition yet still engender an American spirit. He understood it was possible to use a visual vocabulary without being beholden to its source or history; one need not reject French modernism wholesale to be an American modernist.

Fig. 4. Fauve Landscape with Red and Blue by Maurer, c. 1909. Oil on board, 22 by 18 1/2 inches. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas; photograph by Dwight Primiano.

Maurer’s introduction to cubism dates to his formative years in Paris, when he first encountered the cubist experiments of Picasso through his intellectual mentor Leo Stein. His knowledge was enhanced by his association with vanguard dealers like Ambroise Vollard and through works on view at the Salon des Indépendants. In these early years Maurer cautiously processed the innovations of the great cubists while fervently maintaining his allegiance to fauvism. He judiciously applied cubist components in his work, as in Fauve Landscape with Red and Blue (Fig. 4), where cubist spatial perspective is paired with brilliant fauve color.

Maurer’s return to New York came on the heels of the 1913 Armory Show, which introduced the European avant-garde to Americans, turning the American art world on its head. As viewers grappled to understand the new experimental art, two authors sought to elucidate cubism: Arthur Jerome Eddy (Cubists and Post-Impressionism, 1914) and Willard Huntington Wright (Modern Painting: Its Tendency and Meaning, 1915). Despite their herculean scholarly efforts, cubism would not have a dominant presence in the States during the war years, and it only came into greater focus in the 1920s, when American collectors John Quinn, Walter Arensberg, Dikran Kelekian, and Arthur B. Davies emerged as staunch defenders of this progressive art. They demonstrated support by acquiring important examples for their collections, while organizations like the Société Anonyme (founded in 1920 by Katherine Dreier, Marcel Duchamp, and Man Ray) rallied to support cubism as well.4 Few American museums featured cutting-edge European art in the early 1920s, and substantial museum support for cubism took time to materialize. It wasn’t until 1926 that the Société Anonyme organized the International Exhibition of Modern Art at the Brooklyn Museum, a landmark show of approximately three hundred works of avant-garde art. By the close of the decade, the Museum of Modern Art opened its doors, bridging the gap between European modernism and the American public. European cubist art had at last become a prominent fixture in the New York art world. Not surprisingly, its increased presence gave rise to another wave of attacks by conservative critics, who decried it an art without consequence and claimed it was no longer even avant-garde.5

Fig. 5. Still Life with Pears by Maurer, c. 1930–1931. Oil on board, 26 by 36 inches. Addison Gallery of American Art, Phillips Academy, Andover, Massachusetts, © Addison Gallery of American Art/ Museum Purchase/Bridgeman Images.

This is the charged backdrop against which Maurer created his cubist imagery. Whether cubism was current or passé had little bearing on his artistic trajectory. Maurer had assembled a diverse artistic vocabulary and was now poised to bring it all together in a cubist idiom: the artful arrangement of forms, the abstract mapping of space, the rich chromatics of fauvism, the solidity of Cézannesque structure, and the transience of time and space (Fig. 8). Maurer would draw from his bag of tricks, mining his past to take him forward, now realizing his full potential as an innovator and creating the most self-assured paintings of his modernist years such as the monumental Still Life with Pears (Fig. 5). As a cubist, Maurer pulled rabbits out of a hat, like a magician in continual performance. One cubist painting was more inventive and ambitious than the last. As a group, this work catalyzed the possibility of something greater and more daring.

Fig. 6. Brass Bowl by Maurer, 1927–1928. Oil on composition board, 21 3/8 by 18 1/8 inches. Weisman Art Museum, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, gift of Ione and Hudson D. Walker.

While Maurer experimented with cubist-inspired forms in the early 1920s, his most fully conceived cubist pieces date from 1928 to 1932.6 These works don’t adhere to any one cubist formula. Some drew more literally on the early analytical cubism of Picasso and Braque, where surfaces intersect at random angles and objects and planes penetrate one another in an ambiguous space. Most of Maurer’s cubist works, however, were rooted in the experimental techniques of synthetic cubism, with flat planes of solid color shown from multiple viewpoints but with fewer planar shifts. Maurer darted back and forth between the two, pulling what he needed, always leaving his own imprint on the final product. He moved naturally between painting styles, producing masterpieces like Brass Bowl (Fig. 6), which capitalizes on the bold flat planes of color typical of synthetic cubism, and Still Life with Croissant (Fig. 3), a fusion of analytical and synthetic cubism with an attendant strategy of perspectival disruptions.

Fig. 7. Still Life with Candlestick, Brass Bowl, and Yellow Drape by Maurer, c. 1928. Oil on gessoed board, 18 by 21 1/2 inches. Collection of Tommy and Gill LiPuma.

Still Life with Three Pears (Fig. 9), a painting shown posthumously at the Museum of Modern Art in 1945, is one example of Maurer weaving cubist aesthetics together with the explicitly rich color of fauvism. Here Maurer grounded his abstraction in observation, extracting the essence of the simple objects he painted, choosing readily accessible, everyday items: fruit, croissants, a simple wooden table draped with fabric. He used random decorative objects from his studio repeatedly in different paintings, changing their context, inevitably transforming their meaning. One favorite object was a chalice, which anchors such compositions as Still Life with Red Chalice (Fig. 10). Maurer typically placed his objects squarely in the middle of the picture. Here, they are set against an open ground where the still life is anything but still; they are suspended in a state of Bergsonian motion. Our viewpoint is in flux as we simultaneously experience the painting from multiple vantage points. The different textured passages, including the yellow dotted area in the upper left and the sketchy translucent planes on the far right, guide us in and around the central arrangement, pulling us back and forth in space. The artful pairing of sensuous, rich color with disruptive spatial oscillations had by now become a hallmark of Maurer’s cubist still lifes. Bright chromatics powerfully moor this composition, while in Brass Bowl, a tour de force of synthetic cubism, wild color reigns supreme.

Fig. 8. Still Life with Cup by Maurer, c. 1929. Oil on composition board, 18 1/8 by 21 3/4 inches. Weisman Art Museum, Walker gift.

The New York gallerist Erhard Weyhe showed Maurer’s cubist still lifes in 1931 to significant acclaim. A writer for Art News was among those who observed that the artist was charting a course toward his greatest triumphs: “It is in the still-life arrangements that I think Maurer has made the most definite advances, his treatment of forms is much more plainly carried through, more coherently related, and he is obviously heading toward a personal equation that will ultimately give the final cachet to his style. With three of four more years’ pursuit of these newly established formulae, Mr. Maurer should emerge very much a master modernist.”7

Fig. 9. Still Life with Three Pears by Maurer, c. 1930–1932. Signed “A. H. Maurer” at lower right. Oil on board, 18 3/8 by 21 7/8 inches. Private collection.

Post-mortem, Hilton Kramer understood what Maurer had achieved in such works when he wrote in 1969: “[I]t was cubism that ultimately led to Maurer’s most powerful pictures, for in the end he came to have a very strong hold on the kind of pictorial syntax that cubism made possible. Indeed, in his finest paintings—in my view, these are the late still lifes—he was able to apply what he had learned of fauvist color to the more rigorous syntax of cubist construction.”8

Maurer would die in August 1932, but during his last years he used all the tools at his disposal to construct innovative still life orchestrations. The visual wit evident in his earlier fauve paintings continued to guide him. In Brass Bowl sliding conceptions of reality prevail: a radiator is not just a radiator but also a clever allusion to an architectural structure. There is a gesture toward the surrealist conception of spatial ambiguity and anti-rationalism as expressed in such works as Giorgio de Chirico’s Turin Spring, 1914 (Fig. 15).9 In Still Life with Doily and Still Life with Pears the concept of visual puns is put to the test as Maurer pits artifice against reality. We are left to discern whether the doily is real and collaged onto the painting’s surface, or something constructed by the artist as a trompe-l’oeil effect.10 Was Maurer attempting to subvert representation, or did he introduce this pictorial ploy to usher viewers into a visual tug of war, leaving them in a state of uncertainty?

Fig. 10. Still Life with Red Chalice by Maurer, c. 1928. Signed “A H Maurer” at upper right. Oil on board, 18 by 21 3/4 inches. Myron Kunin Collection of American Art, Minneapolis.

Fig. 11. Still Life with Pear and Indian Bowl by Maurer, c. 1928–1930. Oil on Masonite, 13 3/4 by 30 1/2 inches. Private collection; photograph courtesy of Stacey Epstein Fine Art, New York.

Fig. 12. Still Life with Orange and Apple by Maurer, c. 1928–1932. Signed “A H Maurer” at lower left. Oil on canvas, mounted to board, 18 by 21 1/2 inches. Myron Kunin Collection of American Art.

As was his forté, Maurer disrupted the realm of reason. He moved outside the normal parameters of association to challenge perception. The blank canvas was a clean slate: a chance to reinvent and reorder the world, an opportunity to defy conceptual understanding. Maurer achieved this through two means. One was through the physical manipulation of structural space, through a layering and juxtaposing of transparent, translucent, and overlapping forms, which allowed him to create alternate planes of reality, as in Still Life with Croissant. Secondly, he demands we acknowledge the surface materiality of a painting through his focus on paint and painterly ploys. Maurer demonstrated how keenly attuned he was to the physical surface of his pictures in such paintings as Still Life with Red Bowl and Black Bottle (Fig. 13) and Cubist Still Life (Fig. 14). He fully recognized that what he painted was now unimportant—it was how he painted it that mattered.

Fig. 13. Still Life with Red Bowl and Black Bottle by Maurer, c. 1929–1930. Oil on gessoed board, 21 3/4 by 18 inches. Private collection; Stacey Epstein Fine Art photograph.

Fig. 14. Cubist Still Life by Maurer, c. 1928–1932. Oil on gessoed board, 21 5/8 by 18 inches. Private collection.

In the last decade-and-a-half of his career Maurer had become keenly attentive to the primacy of touch, the tactile and elastic nature of paint, and the process of painting itself. His attention to the physical properties of his medium and the integral role they played in the painting process anticipates the abstract expressionists’ focus on these issues. Few others in the late 1920s could build up a painting surface as beautifully and as evocatively as Maurer. He was propelled by an intrepid experimental spirit and probed beyond the surface appearance of objects—artfully dismantling, arranging, and rearranging the world around him to create among the most compelling cubist works of the 1920s and ’30s.

Fig. 15. Turin Spring by Giorgio de Chirico (1888– 1978), 1914. Signed “g. de Chirico” at lower center along red edge. Oil on canvas, 48 7/8 by 39 3/8 inches. Private collection, © 2022 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/SIAE, Rome; photograph © Peter Willi/ Bridgeman Images.

1 Paul Rosenfeld, “The Maurer ‘Little Girl,’” New Republic, vol. 73, no. 30 (November 30, 1932), p. 73.

2 Ibid.

3 Margaret Breuning, “Brooklyn Museum Shows International Exhibition of Modern Art,” New York Evening Post, November 27, 1926. See also Thomas Craven, “The Curse of French Culture,” The Forum, vol. 82 (July 1929), pp. 62–63.

4 For instance, the Whitney Studio Club mounted Recent Paintings by Pablo Picasso and Negro Sculpture, an exhibition, organized by Marius de Zayas and Juliana Force in 1923, that showed cubist art by Picasso in conjunction with African objects. For a detailed account, see Julia May Boddewyn, “Chronology of Exhibitions, Auctions, and Magazine Reproductions, 1910–1957,” in Michael Fitzgerald, Picasso and American Art (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art/New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006).

5 Bruce Weber, “Toward a New American Cubism,” in Weber, Toward a New American Cubism (New York: Berry Hill Galleries, 2006), p. 11. See also John Cauman with an introduction by Stacey Epstein, Inheriting Cubism: The Impact of Cubism on American Art, 1909–1936 (New York: Hollis Taggart Galleries, 2001).

6 Exact dating of these works has long been unclear. Sheldon Reich first established an order in 1973, dividing them into stylistic groups tracking the evolution of their formal properties. Descriptive passages in contemporary reviews support his dates. William C. Agee sought to further establish the sequence of these works based on the pictures’ internal evidence. See William C. Agee, “The Tommy and Gill LiPuma Collection: Exploring American Art, 1906–1946,” in Agee and Bruce Weber, High Notes of American Modernism: Selections from the Tommy and Gill LiPuma Collection (New York: Berry Hill Galleries, 2002), p. 28. 7 Art News, vol. 24, no. 17 (1931), p. 9.

8 Hilton Kramer, “The Ordeal of Alfred Maurer,” New York Times, February 16, 1969. See also Kramer, “Getting to Know Maurer,” in Alfred H. Maurer: The Cubist Works (New York: Salander O’Reilly Galleries, 1988).

9 Surrealism shared much of the anti-rationalism of dada, the movement out of which it grew.

10 Maurer stenciled the doily onto the painting surface for graphic visual effect. Collage became not only an underlying structural element but also a defining element in the composition. Maurer’s experiments with collage were likely inspired by Arthur Dove’s collages from the mid-1920s.

STACEY B. EPSTEIN is an art historian specializing in twentieth-century American art. She is the principal of the advisory firm Stacey Epstein Fine Art.