Clarence H. White, one of the pioneers of the pictorialist style in photography, is having his first retrospective in more than a generation, a traveling show now on view at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College. Drawing heavily on holdings at the Princeton University Art Museum and at the Library of Congress, Clarence H. White and His World, which originated at Princeton, surveys the period from 1895 to White’s death in 1925. His career spanned one of the most interesting periods in American photographic history, a crucible that encompasses Alfred Stieglitz’s Photo-Secession, the fledgling commercial era, and the rise of documentary “straight photography” in the twenties.

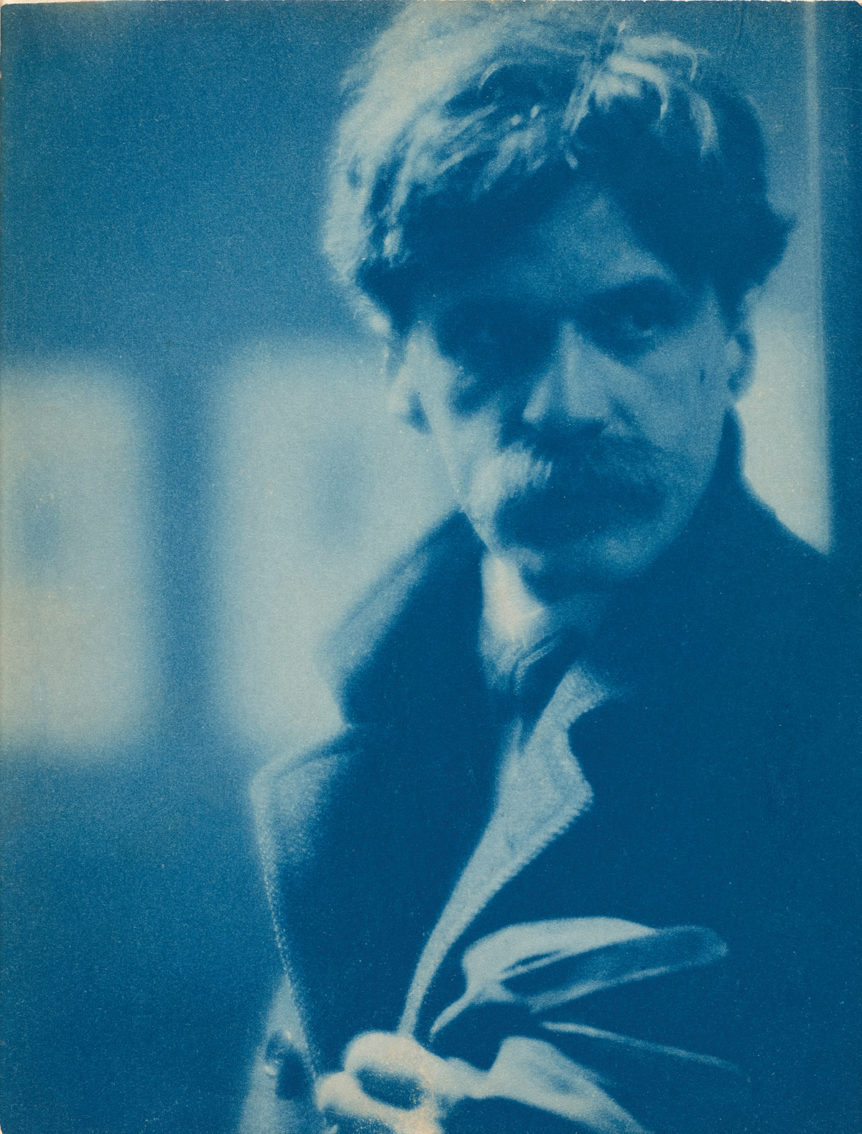

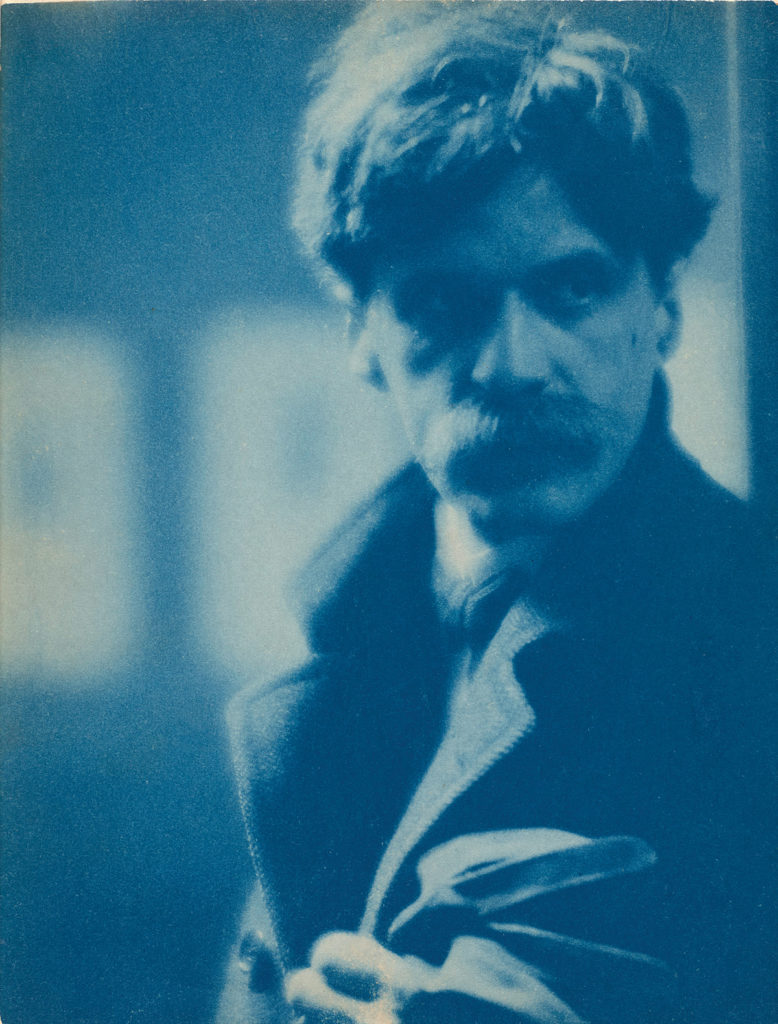

Alfred Stieglitz by White, 1907. Princeton University Art Museum, Clarence H. White Collection, all images courtesy of the Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey.

At the time that White took up the camera, in 1894, photographers were struggling to establish the medium as an artistic one. Unrivaled sharpness was photography’s best attribute, but that was the quality that made photography useful to commercial and scientific interests. Sharp photos were associated in the public mind with advertisements and textbooks. To differentiate themselves, art photographers directed their efforts toward capturing mood—making use of papers with reduced contrast, alterations to the negative or print, and soft focus, to produce images in a style that became known as pictorialism.

Girl with Mirror by White, 1912, printed after 1917. George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York.

White made his name with carefully-produced domestic and plein-air pictures that suggest a compositional indebtedness to painters of his day, particularly the dreamy, atmospheric scenes of Thomas Wilmer Dewing and the bold perspectives and formal arrangements of William Merritt Chase and John White Alexander. His process was labor-intensive. After developing the negatives, White made a series of cyanotype test prints, playing with dimensions, proportions, and other variables. The final print was made in velvety platinum, which White then expressively retouched, encircling his models’ faces with aureolae of gouache, tracing classically draped muslin skirts with graphite or black chalk. The prints were sometimes shaped into lunettes or cut into triptychs, and fitted with custom-made oak frames.

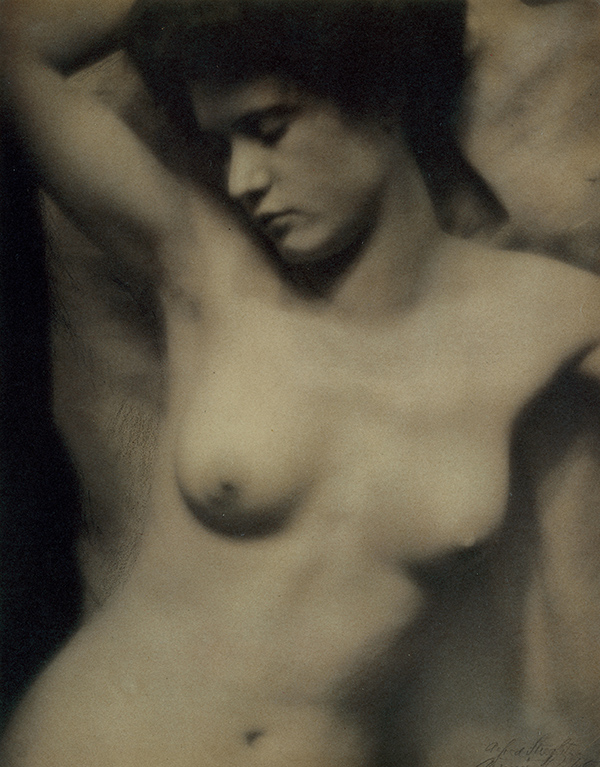

Torso by White and Alfred Stieglitz, 1907. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Alfred Stieglitz Collection.

White exhibited his work frequently and made the acquaintance of Stieglitz, art photography’s great promoter and practitioner, shortly after winning a grand prize at the Pittsburgh Salon of 1898. In the next few years, White became a fixture in the heady art photography group known as the Photo-Secession. Several portraits in Clarence H. White and His World—White’s of Stieglitz, F. Holland Day, and Alvin Langdon Coburn; Coburn’s and Edward Steichen’s of White—exemplify the work of leading lights in the clique, and a series of pre–Georgia O’Keeffe nudes that White shot with Stieglitz underscore the collaborative nature of their enterprise.

Telegraph Poles by Clarence H. White, 1900, printed after 1917. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

White quit his job as a Newark, Ohio, accountant in 1904, moved to New York in 1906, and to make ends meet sold prints and taught photography classes. He counted Dorothea Lange, future filmmaker Ralph Steiner, illustrator Bertha Parker Hall, and Paul Outerbridge among his pupils, a group Davis curator Claire C. Whitner describes as “the first wave of a very visual-centric modernism.” Devoted to art, White nonetheless guided his students in their pursuit of commercial applications for photography, such as fashion, while bringing his arts and crafts principles to bear in the intensely hands-on picture-making process he taught. “This is not photography as mechanical reproduction,” says Anne McCauley, who organized the show at Princeton. The fruits of White’s example were many and long-lasting. “The impulse towards documentary is all in the White School and it comes straight out of the Progressive Era,” she says. “The moral impulse behind Dorothea Lange is there in this moment of pictorial photography.”

Portrait Study in Pink (The Pink Gown) by John White Alexander, 1896. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, J. Harwood and Louise B. Cochrane Fund for American Art and gift of Juliana Terian Gilbert in memory of Peter G. Terian.

By the early 1920s the successor style to pictorialism, “straight photography,” had come to prominence, advanced in blistering polemics by the likes of Steichen and Paul Strand. Sharp focus was in, soft focus was out, and White’s work quickly began to seem dated. But according to McCauley, some of the new straight photographers were none other than pictorialists who reprinted their old work on high-contrast gelatin silver paper. Stieglitz himself did it. “What makes [White’s work] look more traditional to our eyes is that we have rejected any kind of soft focus,” says McCauley, “There is no moment where suddenly things are quote unquote ‘modernist.’”

Take another look at White’s Telegraph Poles, shot in 1900. In it, White marries attention to two-dimensional composition—attended by radically-close cropping—to the sort of gritty urban subject matter favored by twentieth-century documentary photographers. Even with its sepia tone, the image is strikingly . . . well, modern.

Clarence H. White and His World: The Art and Craft of Photography, 1895–1925 is on view at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College to June 3.