This year, unobserved and thoroughly unworthy of commemoration, a sordid milestone was passed: Madison Square Garden, one of the ugliest buildings ever conceived, has now risen over Midtown Manhattan for fifty-three years, exactly as long as the building it replaced, the old Pennsylvania Station. If you are not a New Yorker of long-standing, the significance of this fact may not register as forcefully as it should: the destruction in 1963 of McKim, Mead and White’s imperious palace of transportation, stretching from Seventh Avenue to Eighth between 31st Street and 33rd, represented modernism in all of its militant mid-century triumphalism. New York has not yet recovered from this violation of its heritage. Perhaps our only consolation is that that one act of vandalism almost single-handedly fueled the landmarks preservation movement in America, and such a desecration, surely, would be unthinkable today.

Through an almost providential stroke of good fortune, however, another building of exactly the same size, designed by the same architects and conceived in a similar style—the James A. Farley Post Office Building—stands just to the west of the old Penn Station, covering the blocks from Eighth Avenue to Ninth, and from 31st Street to 33rd. And, as of January 1, 2021, it has been gloriously reborn as the Daniel Patrick Moynihan Train Hall. For generations to come, Amtrak and Long Island Railroad trains will depart the city from Moynihan in all directions.

The new station takes its name from the man who represented New York in the United States Senate from 1977 to 2001 (two years before his death) and who lobbied for years to transform the post office into a train station to replace the one we had lost. There seems to have been a personal element to Moynihan’s quest: he had spent part of his childhood in nearby Hell’s Kitchen, and he liked to tell of how, as a boy growing up during the Great Depression, he shined shoes in the old Penn Station.

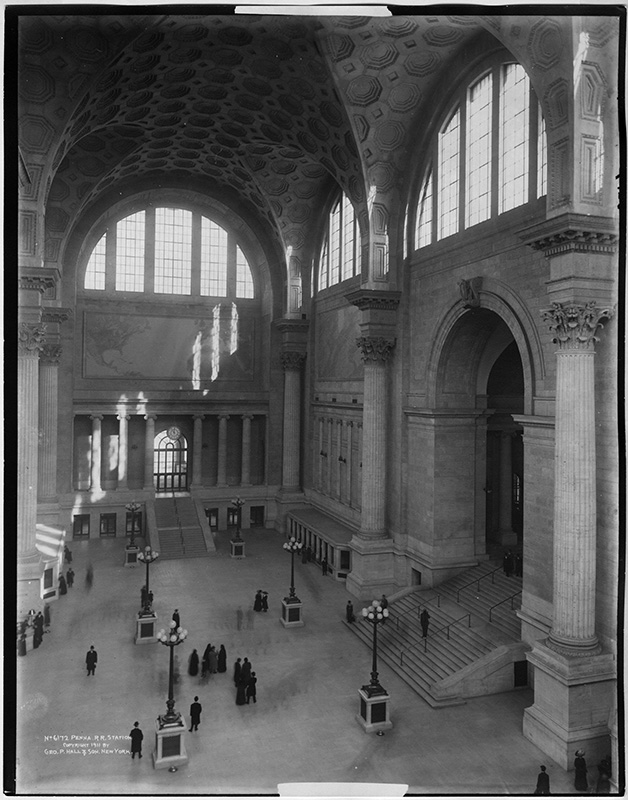

Perhaps the building that houses the Moynihan Train Hall, completed in 1914, lacks some of the majesty of the old Penn Station, from 1910, but surely it is good enough. Still, the differences in their designs reflect the very different functions they were meant to serve. The breathtaking volumes of old Penn Station (Figs. 2, 5), based on the Baths of Caracalla and Diocletian in Rome, were designed to dazzle and overawe the hordes of travelers who passed through them. The Farley Post Office, by contrast, was intended to welcome the public only into a narrow strip of space about ten yards deep that unfurled along Eighth Avenue: the rest of the vast structure was used for mail-sorting and for housing the post office’s bureaucracy. Insistently uniform in height, this low-lying structure has twenty Corinthian columns along its main, east-facing entrance, to which the visitor ascends by means of a majestic flight of steps that stretches along most of the facade. On either side of these columns stands a pavilion whose tall, coffered niche is flanked by pilasters. The attic level is enlivened by several flat-topped windows beneath a row of bronze acroteria at its summit. This design of the Eighth Avenue facade largely persists along the building’s three other sides, except that there pilasters have replaced the freestanding columns.

Because the Farley Post Office was not originally designed as a major thoroughfare, the New York office of the inveterate architectural firm Skidmore, Owings, and Merrill (now SOM), which oversaw its latest transformation, had their work cut out for them. The most conspicuous change they have wrought was the fundamental re-conception of the vast, lightflooded central courtyard, where, for nearly a century, the city’s mail was sorted before distribution to the five boroughs. Its crystalline glass ceiling is supported by three leviathanic trusses whose sturdy iron span, held together by exposed nuts and bolts, brings a suitably industrial air to the entire project. This retro sense is enhanced by a large, endearingly art deco clock, twelve feet tall and designed in the offices of New York architect Peter Pennoyer, that hangs down from the central truss and seems to float benignly above the entire room (Figs. 1, 4). This thrilling space is surrounded by galleries on several sides, from which visitors can look down into it. In addition to providing access to seventeen of the stations twenty-one tracks, it has a large waiting area and, like the galleries, will eventually contain restaurants and retail.

Scarcely less satisfying is a smaller courtyard to the west, similarly filled with light, which is reached through two mid-block entrances, one on 31st Street, the other on 33rd. As was the case with Manhattan’s recently unveiled Second Avenue subway, contemporary art has been used to enliven this project. On the ceiling of the 33rd Street entrance one finds Kehinde Wiley’s Go, a richly colored stained-glass triptych depicting break dancers (Fig. 7). Adorning the ceiling of the entrance on 31st Street is Elmgreen and Dragset’s The Hive, which invokes a mythic art deco New York skyline of the 1930s through a dense cluster of largely imaginary skyscrapers hanging upside down (Fig. 6).

The principal weakness in the design is the way in which, along Eighth Avenue, one enters the structure by descending into the basement level of the pavilions on either side of the central colonnade. The entire point and strategy of the revised building ought to be—as it was at the old Penn Station—that one enter by ascending to the main level and that the reward for that ascent is the grand vista that opens up before you. The charming old post office, with its antique teller windows, is still where it always was, but surely a greater good would be served by transferring that rather diminutive outpost, together with its quaint details, to one side, opening up the entire structure, and building a grand staircase entrance into the main reception area.

Even without that obvious enhancement, however, the new Moynihan Train Hall already goes some distance to redeem the loss of the old Penn Station. Comparing the latter with what replaced it under Madison Square Garden, the architectural historian Vincent Scully famously observed: “Through [Pennsylvania Station] one entered the city like a god. . . One scuttles in now like a rat.” This sorry spectacle represented the collision of two competing and incompatible visions of humanity: the functional and demotic new station under Madison Square Garden stood in opposition to the humanist visions of the old one, whose granite columns exemplified the City Beautiful movement that influenced so much American architecture and urbanism around 1900. Both projects were inherently democratic, but in very different ways. If the new postwar idiom presumed to find virtue and honor in a utilitarian vision of life as lived, the older station embodied the idea that the function of great public architecture was to elevate men and women, to allow them, through the mere process of moving through an inspired space, to attain to that elevated condition that was their true birthright.

Not the least charm of successful public buildings consists in this: that, however splendid the homes of Morgan and Vanderbilt once were, however enviable the lofty condos that now float a thousand feet above Central Park, none of them can hold a candle to the granite and limestone palaces of the old Penn Station and the new Moynihan Train Hall, with their domes and colonnades, their brass fixtures, and their marble floors. As with all successful public architecture, these buildings have opened their doors freely to every man, woman, and child of the republic and we are all ennobled in the process.