Although not invariably, the course of an artist’s career often takes the form of a parabolic arc. Tastes change, one art-world “ism” replaces another, and work that was once embraced— conventional or otherwise—loses currency. Some painters, whether responding to the marketplace or their own creative impulses, pivot to a new style, and find themselves in the swim again. Committed to realism all his life, Luigi Lucioni was content to stand on shore. Although he appreciated Cézanne and Matisse in his formative years, he was never swayed by them and the later permutations of abstraction. Thoroughly influenced by his visits in the 1920s from his adopted home in America to his native Italy, he took the masters of the Renaissance as his model. As he told an interviewer in 1971: “I never worried about whether I was stylish or not stylish.”1

Fig. 2. Self-Portrait, 1949. Signed and dated “Luigi Lucioni 1949” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 32 by 26 inches. Southern Vermont Arts Center, Manchester, gift of Douglas Mariboe.

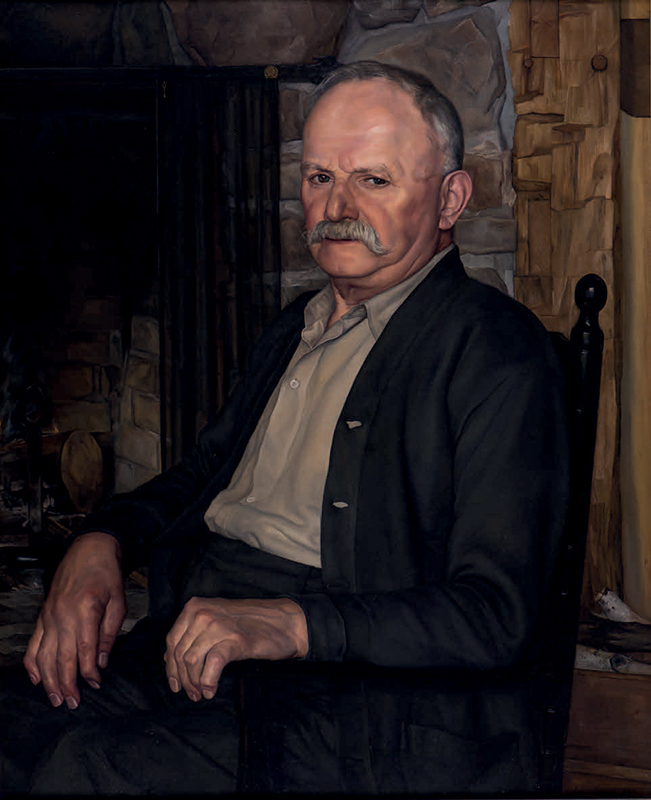

Fig. 3. My Father, 1941. Oil on canvas, 34 1/4 by 28 1/4 inches. Shelburne Museum, bequest of Luigi Lucioni; photograph by Andy Duback.

Born in Lombardy in 1900 and raised in New York, Lucioni was a longtime resident of Vermont, where the Shelburne Museum—which came into a cache of the artist’s work after his death—is presenting the exhibition Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light. The show is comprised of landscapes, portraits, still lifes, and etchings—works that rehearse the artist’s evolution and examine his role in defining, sometimes with an almost precisionist clarity, New England regionalism in the first half of the twentieth century.

Having shown a precocious talent for draftsmanship, Lucioni won admission to study art at New York’s Cooper Union at age fifteen, and, four years later, at the National Academy of Design. His initial interest centered on nudes and portraits and even after a 1924 fellowship from the Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation allowed him to paint en plein air at Laurelton Hall, the Louis Comfort Tiffany estate on Long Island, he remained dismissive of landscapes. But a series of visits back to Italy that began in 1925 prompted Lucioni to reassess the genre. In time, he came to identify himself as primarily a landscape painter, and, in fact, disparaged his ability as a portraitist. (Which was surely misplaced self-criticism. Modern Light includes a number of portraits that attest to Lucioni’s skill, including likenesses of individuals in the artist’s bohemian circle of friends, such as fellow artists Jared French and Paul Cadmus, as well as of his father, and of entertainer Ethel Waters.)

Lucioni enjoyed professional success early on, beginning with his first New York show at Frederic Newlin Price’s Ferargil Galleries in 1927. His third solo show there, in 1930, reflected his recent visits to Italy, with work that captured views of his hometown north of Milan, as well as of Orvieto, San Gimignano, and Siena. In 1931, collector and Shelburne Museum founder Electra Havemeyer Webb became a patron. The following year, the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York purchased the still life Dahlias and Apples, making Lucioni the first contemporary American artist to be represented in the institution’s collection.

While deemed retrograde by some critics, his popular appeal was considerable, aided in part through the inexpensive prints of his work issued by Associated American Artists, which was founded in 1934 to bring art into the homes of the general public. In 1937 Life magazine christened Lucioni—who had been visiting family in Vermont since his teens—the “painter laureate” of the Green Mountain State. He never apologized for his realist painting style. In a short film profile released in 1969 (available for online viewing at the Vermont Archive Movie Project Database), the artist said, with the gentle bluntness of age: “I think the public has come to a point where they want to understand what paintings are all about. If you paint a tree, they want it to look like a tree, not the essence of a tree, or the spirit of a tree, or how you feel about a tree.”2

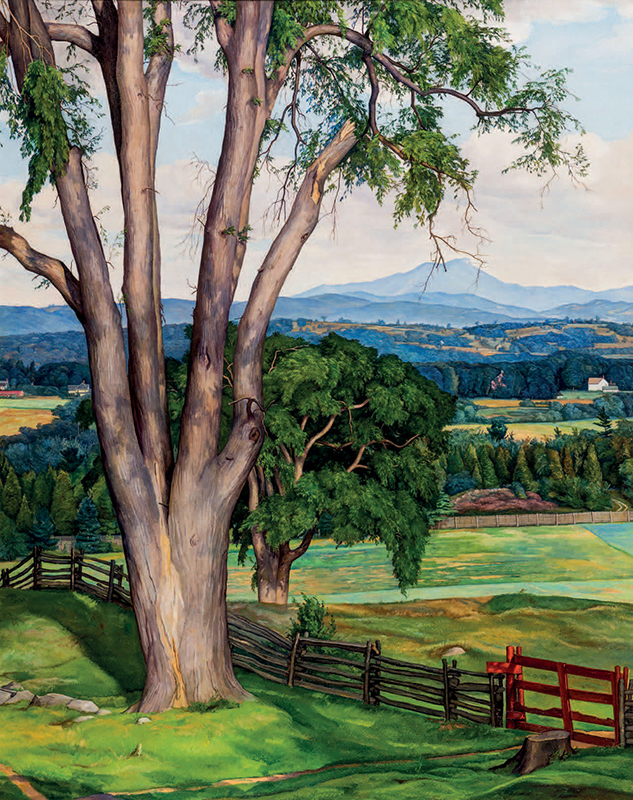

Although Lucioni found the hills and valleys of Vermont similar to the landscape of northern Italy, working in New England required a different sort of engagement. “Italy is so beautiful and picturesque, all you do is set up an easel and copy,” he explained, “but in Vermont, on the other hand, you have to compose.”3 Grounded by barns, fences, and church steeples, Lucioni’s landscapes are remarkable, not for any implied narrative—in fact, his images are usually unpeopled—but for their pronounced and profound sense of distance. Evocative of landscape as expressed in fifteenth-century Italian art, they take the eye far. Less idealized and more central to the composition than most quattrocento vistas, Lucioni’s receding space nonetheless projects a similarly distinctive atmospheric effect, one that, in some respects, suggests that the essence of the painting somehow lies beyond those hazy hills. Interestingly, when he spoke of his fascination with visual depth, Lucioni included Claude Lorrain as an artist whose ability he esteemed for “the wonderful sense of miles he gets inside of his paintings.”4

Lucioni could be self-effacing when assessing his work, and was quick to admit how far short he felt he fell of those artists he admired most—Raphael, Piero della Francesca, Mantegna. “I have these days when I am terribly discouraged. . . . But what can I do? I mean, if I don’t have any greater talent than this.”5 By the 1970s, Lucioni had been working in Vermont for forty years (he also kept a studio in New York), and while he knew his art was not in vogue, he seemed content with the trajectory of his career, one that never veered from a dedication to clear-eyed representation. “My idea of realism is not what you see,” he said, “but it’s to create what is there in reality.”6

Luigi Lucioni: Modern Light is on view at the Shelburne Museum to October 16. The exhibition catalogue is available from Rizzoli Electa.

1 Robert Brown oral history interview with Luigi Lucioni for the Archives of American Art, July 6, 1971, [p. 6], aaa.si.edu. 2 From the Archives, “The Art of Luigi Lucioni (1969),” written and produced by Garry Simpson, VTPBS video, aired August 28, 2018, video. vermontpbs.org. 3 Ibid. 4 Brown oral history interview, [p. 9]. 5 From the Archives video. 6 Brown oral history interview, [p. 3].

THOMAS CONNORS is an arts writer based in Chicago