The Magazine ANTIQUES | May 2009

When the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s renovated Greek and Roman galleries were inaugurated two years ago, critics acclaimed that majestic design by the architect Kevin Roche (1922–) as a crowning achievement of his career, and an equal triumph for the institution’s longtime director Philippe de Montebello, who soon afterward announced his retirement. Although Roche’s intervention deserved every bit of the widespread publicity it received, the Greek and Roman galleries were only a small part of his master plan of 1971, a monumental undertaking that de Montebello shrewdly finessed with a hidden hand worthy of Cardinal Richelieu. For nearly a century after its founding in 1870, the Metropolitan Museum increasingly encroached on Central Park as if by divine right. But the massive scale of Roche’s scheme, initiated by de Montebello’s grandiose predecessor, Thomas P. F. Hoving, provoked an unprecedented public outcry. In order to win city planning approval, the museum swore off future outward expansions and thus far has stuck to its vow. Nonetheless, despite that finite (though ample) footprint, the museum since then has nearly doubled its floor space through an internal space-planning miracle de Montebello has termed, with notable understatement, “a domino game.” Because of his stealth strategy to avert local opposition, each successive increment was executed as quietly as possible, and only now is this monumental undertaking being recognized among de Montebello’s most formidable accomplishments.

For nearly a century after its founding in 1870, the Metropolitan Museum increasingly encroached on Central Park as if by divine right. But the massive scale of Roche’s scheme, initiated by de Montebello’s grandiose predecessor, Thomas P. F. Hoving, provoked an unprecedented public outcry. In order to win city planning approval, the museum swore off future outward expansions and thus far has stuck to its vow. Nonetheless, despite that finite (though ample) footprint, the museum since then has nearly doubled its floor space through an internal space-planning miracle de Montebello has termed, with notable understatement, “a domino game.” Because of his stealth strategy to avert local opposition, each successive increment was executed as quietly as possible, and only now is this monumental undertaking being recognized among de Montebello’s most formidable accomplishments.

On May 19, the former director’s successful coup will be reconfirmed when the best-known portions of the museum’s American Wing are unveiled after a thoroughgoing reconception, reorganization, and renovation, the second installment of a decade-long program that began in 2001. Since the American Wing was opened, in 1924, its survey of our nation’s decorative arts has ranked with the finest anywhere, but has never been shown to maximum advantage. That spotty presentation was the result of fitful growth, haphazard organization, and the lingering misapprehension that Americana was just not as significant in the big picture of world culture as the rest of the Metropolitan’s encyclopedic holdings.

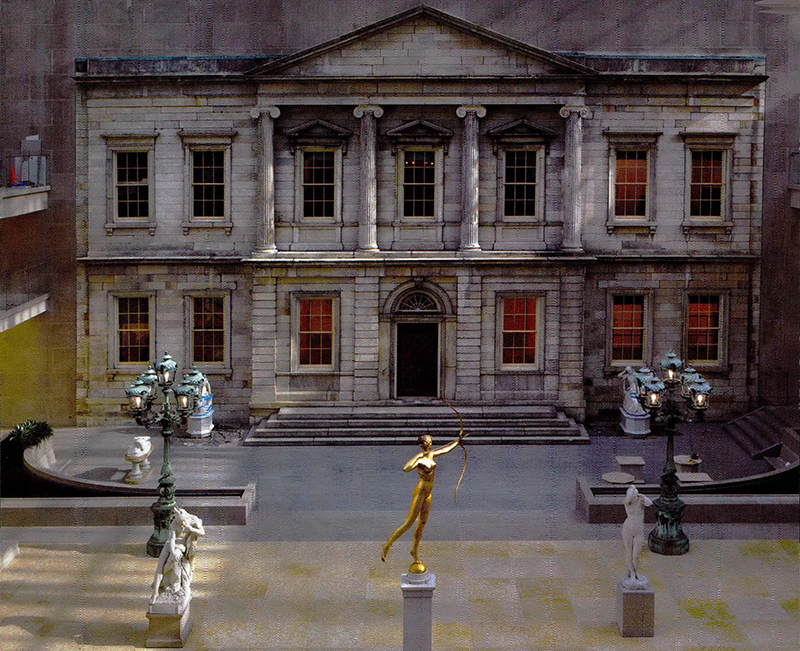

Fanatics may not have minded the American Wing’s jumbled accretion of reconstructed period rooms and drab displays of household objects, but the department’s glorious holdings were often lost on average viewers. In an attempt to engage a broader audience, Kevin Roche, John Dinkeloo and Associate’s new American Wing of 1980 created a dramatic indoor plaza, the Charles Engelhard Court, to attract visitors to this remote corner of the museum (a distant locale that in itself signified the department’s status in the pecking order.). Though Roche’s soaring atrium will seem familiar to most people even after his reworking of it, the space has nonetheless been enormously improved.

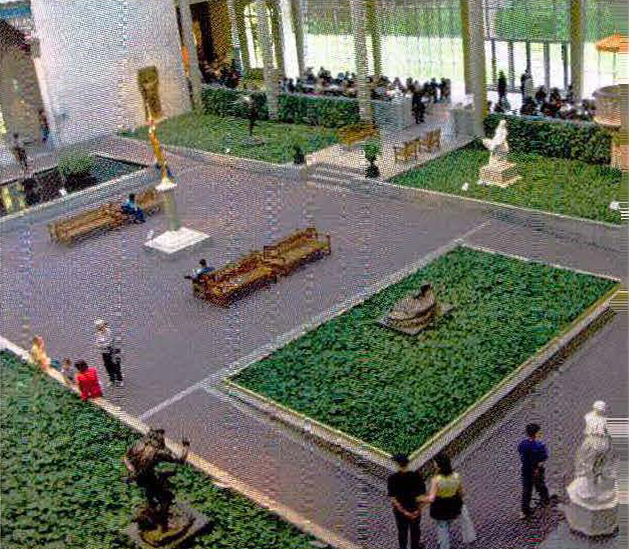

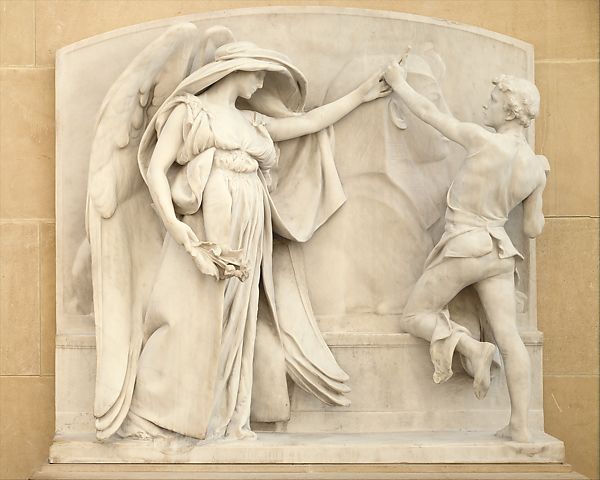

In its initial incarnation, the Engelhard Court brought to mind an upmarket shopping galleria, not least because of the large rectangular planting beds and reflecting pool added by the landscape architect Richard K. Webel (1900-2000). If a museum with standards as high as the Metropolitan’s does not aspire to horticulture on the superior level of, say, the Museum of Modern Art’s Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Sculpture Garden of 1953-1954 by James Fanning (1911-1997), or the landscaping of Louis Kahn’s (1901-1974) Kimbell Art Museum of 1966-1972 in Fort Worth by George E. Patton (1920-1991), then forget it. Now the Met wisely has done just that, and in place of Webel’s banal parterres of generic greenery, the Engelhard Court’s floor has been freed to fulfill its thwarted destiny as a sculpture hall of heroic proportions and paved with simple limestone to create a tabula rasa plaza.

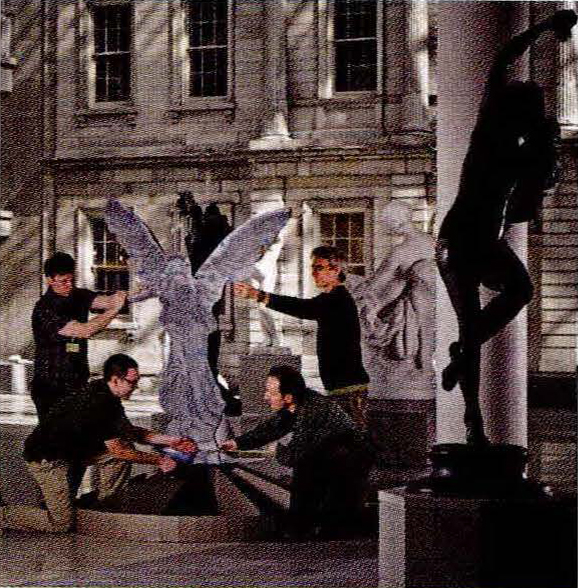

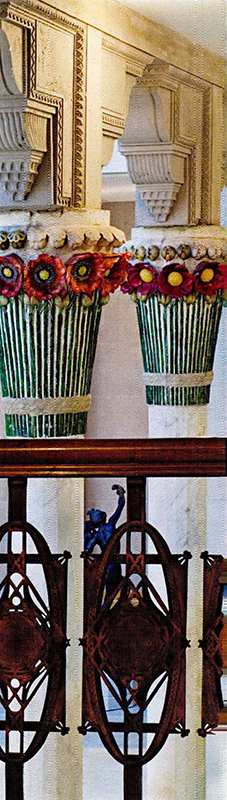

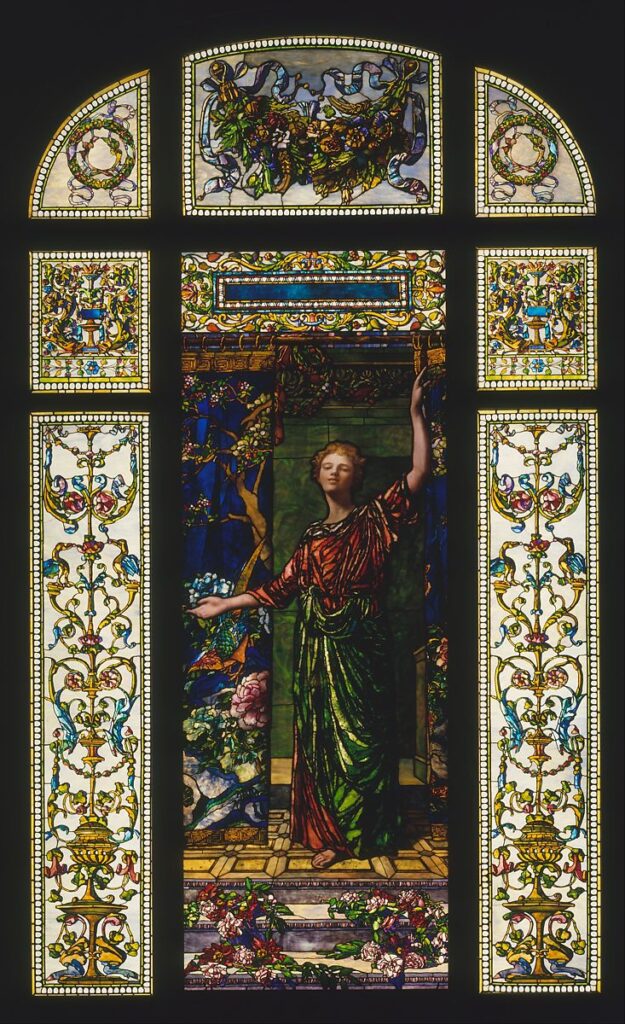

This boldly reclaimed space now effortlessly encompasses more than sixty diverse works, including freestanding sculptures in marble and bronze spanning artists from Hiram Powers (1805–1873) to Harriet Whitney Frishmuth (1880–1980); architectural elements like Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Vanderbilt Mantelpiece of 1881–1883, with flanking caryatids of red-brown marble that always remind me of sequoia trunks; as well as stained-glass windows and mosaics by Louis Comfort Tiffany and John La Farge (see Fig. 6) set into the atrium’s inner walls. Webel’s mingy reflecting pool remains, in deference to popular sentiment, but has been redesigned to accommodate two bronze fountains sculpted by Frederick William MacMonnies (1863–1937) and Janet Scudder (1869–1940).

No amount of remedial renovation could turn the Engelhard Court into an architectural masterwork, yet Roche has made his original space far better than before—not with a thunderbolt strategy like some ambitious young contender, but rather through a host of small adjustments that contribute to a substantial cumulative effect. For example, a third balcony gallery has been added halfway between two existing display areas that adjoin the court’s tilted glass wall overlooking Central Park. Roche’s insertion corrects that elevation’s inelegant proportions and provides the ideal platform for a recent coup—Robert A. Ellison Jr.’s much-admired collection of American ceramics from 1876 to 1956. Beefy brass handrails that gave the existing balconies a vulgar corporate style flourish have given way to discreet matte-metal horizontals that greatly improve the new trio of étageres.

Most of Roche’s refinements are so subtle that they need to be pointed out, as they were to me by Morrison H. Heckscher, the Lawrence A. Fleischman Chairman of the American Wing and leader of this project with Peter M. Kenny, curator of American decorative arts and administrator of the American Wing. When Heckscher became head of the American Wing, in 2001, he convinced de Montebello that the department’s galleries and period rooms were in desperate need of rearrangement. The Francophile director, though no great fan of Americana, agreed to Heckscher’s proposal, no doubt because the American Wing has always been among the museum’s most enduringly popular attractions. Furthermore, Heckscher’s clear conception of how to give it much-needed coherence impressed de Montebello, who never impeded initiatives he knew would benefit the museum, his personal tastes aside. Fine tuning the Engelhard Court was hardly child’s play, but it can seem so in contrast to the complexities involved with the major reorganization of the period rooms, a tour-de-force of revisionist museology. The new chronological progression of interiors from the seventeenth through twentieth centuries seems so familiar and logical that it is hard to believe how much effort was expended. A feasibility study by the New York preservation architect and planner Jean Parker Phifer gave the museum a clearer idea of how the three-story American Wing could be recast to make three centuries of authentic but architecturally disparate spaces easier to navigate and clearer to comprehend. Armed with her report on what was possible, the museum was able to present Roche with a clear vision for him to realize.

Heckscher has spent his entire professional career at the museum, and over the course of those four decades has developed an unrivaled knowledge of what works there and what does not. He has seen superb period rooms neglected because of poor circulation patterns, and masterpiece-crammed vitrines doomed to obscurity if positioned just slightly off the beaten path. Without surrendering to hucksterish impulses, Heckscher, a model of scholarly probity, has nonetheless made moving through the period rooms more propulsive, resonant, and instructive than ever before.

Several period interiors have been assigned new places in the sequence. Three long-exhibited rooms were retired because Heckscher deemed them not good enough for the wing. One strong new addition—from the Daniel Peter Winne house of 1751 near Albany, New York—will be used as a gallery for objects related to the state’s pre-Revolutionary Dutch heritage (see Fig. 9).

And even rooms that were left more or less intact and in place were reconsidered and tweaked in other ways. For example, Heckscher was never happy with the characteristic blue-green painted paneling of the Verplanck Room (see Figs. 11, 12), even though the color had been painstakingly matched to period scrapings and would be familiar to any historic-house buff. He had, however, been much more favorably impressed by that color as it appeared in a historic house in Newport, Rhode Island, but could not figure out why that finish looked so much more convincing until he learned that the American Wing had used a modern latex-base pigment. The linseed-oil based paint used in Newport, applied with brushes rather than rollers, possessed a depth that increased with age and gave a fifty-year-old paint job the aura of antiquity. Now the paneling in the Verplanck Room has been redone in just that way.

Two big problems that long dogged the American Wing have been resolved—or, at least, ameliorated—by this phase of the renovation. It was always such an effort to reach the American galleries, on the northern extremities of the museum’s sprawling complex. The shortest route there from the Fifth Avenue entrance leads through the hangarlike Sackler Wing, which houses the Temple of Dendur, but you would never know that was possible until now because Roche concealed an almost invisible portal to the American Wing directly behind the reconstructed Egyptian shrine itself. A new, impossible-to-miss, clearly labeled doorway has been cut through the rear wall of the Dendur space—a long overdue rectification of a galling functional lapse.

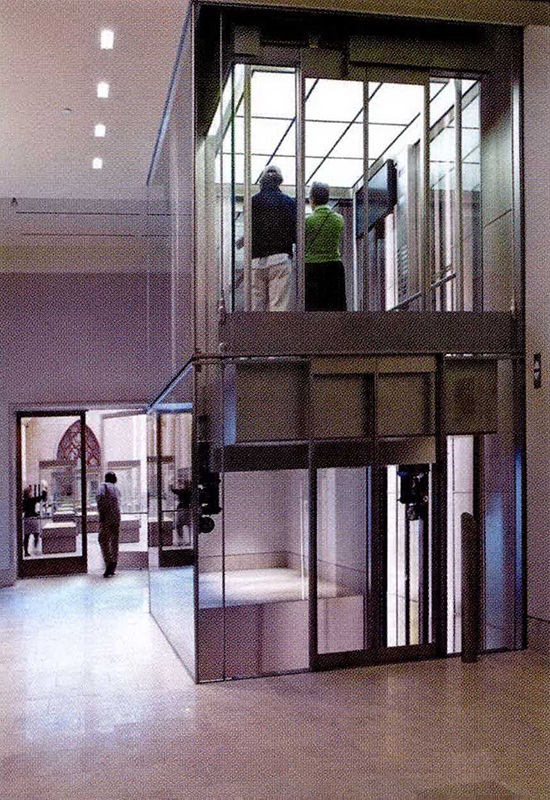

Even after visitors found their way to the American Wing, they often felt confused about where the gallery sequence began. A newly installed public elevator will now whisk viewers up to the top floor, where the march of time begins. Then they will be led downward, story by story, much as the spiral ramp of Frank Lloyd Wright’s nearby Guggenheim Museum does in a more seamless fashion. Heckscher has tightened the journey by eliminating alternate routes and keeping existing doors closed, but you never feel trapped by the strong directional order.

There is still much more to be done before the renovation project concludes, two years hence, but this latest and perhaps decisive phase is certain to expand appreciation for a great national treasure. Even though its officials would insist that the Metropolitan Museum has been deeply committed to the arts of our own country for the better part of a century, the clear subtext of this superb recasting of the American Wing is that ours is a culture worthy of presentation on the same high level as all the other civilizations celebrated by the world’s most inclusive museum.

MARTIN FILLER is a regular contributor to Antiques.