Fig. 1. Mariska Karasz wearing a szűr-inspired coat in a photograph by Nickolas Muray (1892– 1965), c. 1926. Signed “Muray” and embossed “NICKOLAS MURAY/NEW YORK” at lower right. Photograph mounted on board, 10 by 8 inches (photograph) © Nickolas Muray Photo Archives. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in the collection of the family of Mariska Karasz.

A sporty outfit in green and gold—one of the first garments presented in a circa 1929 show of fashions by Mariska Karasz—was inspired, the designer noted, by her visit to San Francisco’s Chinatown. A chiffon ensemble for a luncheon date featured a motif drawn from an African robe she had seen in a museum in Berlin. And for an afternoon of tea and bridge she presented something in blue and chartreuse, prompted, she said, by the memory of the first time she ate ripe green olives.1 The New Yorker praised her clothing as original, beautiful, flamboyantly colored, and befitting “the woman who loves daring in her apparel.”2 Yet a completely different set of creations by Mariska Karasz can be found in museum collections across the country: expressionistic needlework wall hangings made in the postwar years, when she reinvented herself and became a pioneer in the field of fiber art. Together, these two sides of Karasz’s career tell a story informed by a modern aesthetic, an exceptional sense of color and texture, a love of travel, and a depth of knowledge and experience.

Fig. 2. Harlem Valley from the Air by Mariska Karasz (1898– 1960), 1946. French DMC cotton embroidery on cotton, 24 ½ by 25 1/2 inches. Museum of Arts and Design, New York, gift of Rosamond Berg Bassett and Solveig Cox; photograph by Ed Watkins.

Mariska Karasz emigrated from Hungary to the United States in 1912 at age thirteen, and settled in New York, where she was soon joined by her older sister Ilonka Karasz (1896–1981), herself destined to be a noted designer and illustrator.3 The younger Karasz studied design first at Washington Irving High School and then at the Cooper Union, under fashion designer Ethel Traphagen.4 Karasz was independent, a quintessentially modern young woman in both looks and deed. She cut her hair in a bob and sometimes wore pants. Her first published writing chronicled a month-long walking tour through upstate New York she took in 1919 with a friend, artist Henriette Reiss.5

Fig. 3. Phoenix, 1953. Stitched “mk” in monogram at lower right. Linen, wool, and hemp on linen with wooden backing slats; 51 by 70 1/2 inches. Georgia Museum of Art; McKelvey photograph.

At about that time, Karasz’s clothing designs began to garner attention. By the mid-1920s she had established a small studio at 228 Madison Avenue,6 and a distinctive style that combined sleek modern lines with elements crafted using Hungarian folk needlework techniques. Her custom garments featured the colorful floral embroidery typical of the Mezőkövesd area in northeastern Hungary, as well as the delicate appliqué work common to the Buzsák area in the southwest of Hungary. She even adapted a traditional Hungarian men’s overcoat—a szűr—into a trimmer style for her American clients (Fig. 1). The silhouettes and patterns she used, though, were mainly contemporary. Fashion writer Alida Vreeland lauded her “adept” introduction of “skyscraper and other modernistic motifs to her dresses.”7

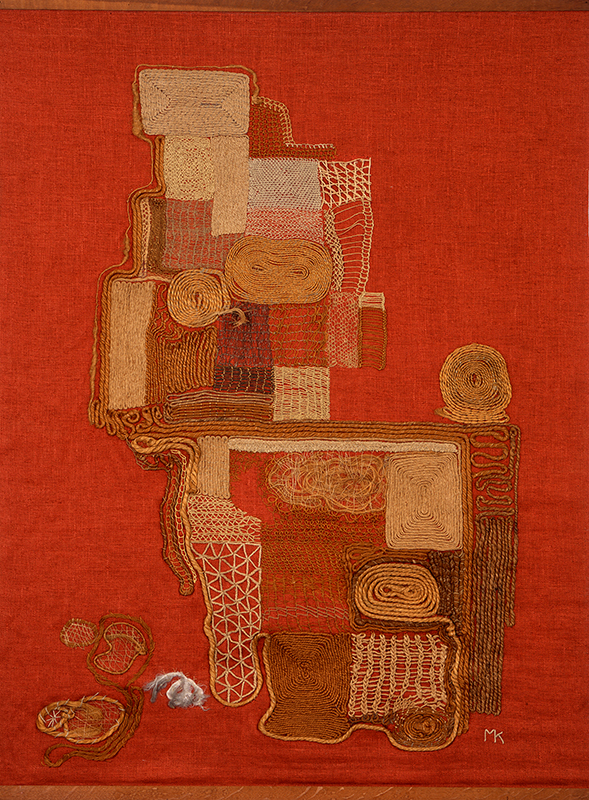

Fig. 4. Ropes on Red, c. 1952. Stitched “MK” in monogram at lower right. Mixed fibers on linen with wooden backing slats; approximately 62 1/2 by 47 ¾ inches. McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Karasz went annually to Europe to see the latest couture collections, select fabrics, and visit the women in Hungary who sewed for her. She used the Social Register to compile mailing lists for her show announcements, and her customers included many well-to-do women, often connected to the arts. She created mostly for individuals, and considered each woman’s personality, hair color, and skin tone as she picked motifs and fabrics. In a 1929 interview, Karasz added that, occasionally, “When there is a modern play in which modern costumes are important, I am asked to design them.”8 Architect Frederick Kiesler purchased Karasz outfits for the cashier and six usherettes at his experimental Film Guild Cinema, at 52 West 8th Street.9

Fig. 5. Elsa De Brun, 1947. Linen and wool, knitted, embroidered, and sewn; 26 1/4 by 22 1/2 inches. Museum of Arts and Design, Bassett and Cox gift; Watkins photograph.

During a 1928 trip to California, where Karasz presented her designs at several venues in the Los Angeles area, she met Donald Peterson (c. 1902–1957), a young naval lieutenant, and they married about a month later. The couple lived in New York City and had a summer place in Brewster, New York, on land given to them by her sister and brother-in-law. After the births of their two daughters, Solveig in 1931 and Rosamond in 1932, Karasz was “appalled at the belaced and beruffled clothes that were on the market for children” and began designing her own, presenting new collections biannually from 1934 to 1941.10 An article in the New York Times described the output of her studio as being to a child what that of “Patou or Schiaparelli is to a woman.”11

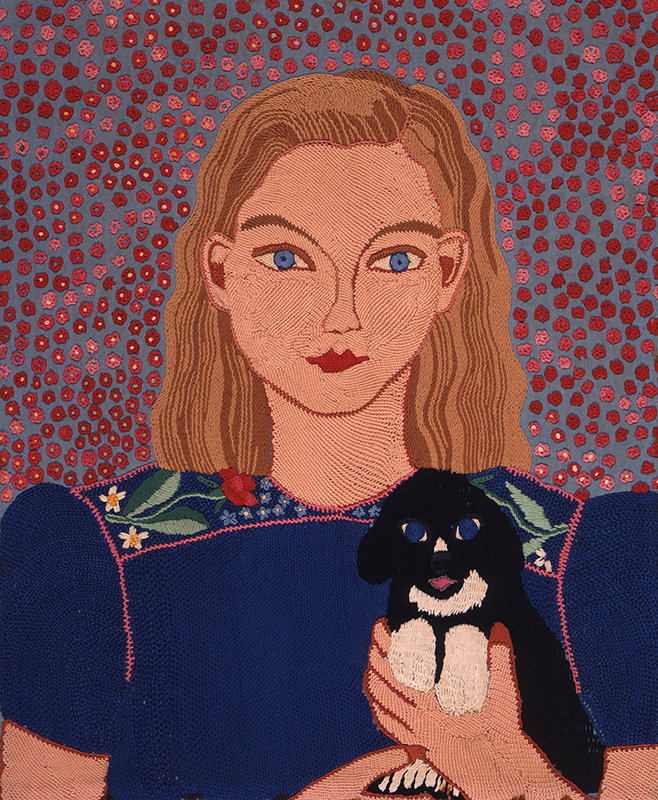

Fig. 6. Rozsika (portrait of Karasz’s daughter Rosamond, titled with her nickname), 1947. Cotton embroidery on cotton, 23 7/8 by 19 3/8 inches. McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Her children’s designs also included Hungarian needlework, took inspiration from around the world, and featured rich and unusual color combinations like cerise with lavender, or lime yellow with royal blue. But Karasz considered the practical needs of a growing child as well. She selected fabrics that were colorfast, sturdy, and washable, and made garments that allowed for easy movement and had fasteners that small hands could manipulate. Karasz gave the outfits engaging names, like Play with Me—a red and white linen sun-suit with a bird appliquéd on the pocket; Gay Shoulders—a dress and panties in sunset colors with bright “peasant embroidery” on the shoulders; and It Is Raining—a blue dress with an umbrella skirt and a top appliquéd with raindrops.12 When the approach of World War II curtailed her travels to Europe, she went to Mexico and Guatemala to find embroidery and new ideas.13

Fig. 7. Rose Leaf dress design, c. 1940. Gouache and graphite on paper, 11 7/8 by 9 3/8 inches.

A combination of forces upended Karasz’s life in the early 1940s. A devastating fire in her Manhattan studio effectively ended her career as a fashion designer and at the same time her marriage began to fail, and eventually ended in divorce. Her daughters, though, again stimulated a new chapter in her work. As their own needlework skills developed, she wrote how-to books, first See and Sew, a Picture Book of Sewing in 1943 for children, then Design and Sew in 1946 for teenagers.14

Fig. 8. Karasz sewing with her daughters Rosamond (1932–2018) and Solveig (1931–2017), in a photograph of c. 1939. 9 1/8 by 6 3/4 inches.

Karasz’s best-known book, Adventures in Stitches: A New Art of Embroidery, from 1949, reflects the transformation of her interest in embroidery from a means of ornamenting garments to an artistic pursuit, the creative endeavor that dominated her postwar life. In the book’s introduction, she explains how she “began to experiment with needle and thread” and soon “realized the limitations of [her] previous knowledge and experience,” adding: “Here was an exciting, unexplored world of stitches that I had never dreamed of . . . a new vocabulary of needlework!”

Fig. 9. Tulip Tree dress design, c. 1940. Gouache, graphite, and ink on paper, 6 by 5 1/2 inches.

For her earliest embroidered wall hangings, Karasz purchased DMC cotton threads in a rainbow of hues and painstakingly used them to create carefully shaded, representational images, including portraits of her daughters (Fig. 8) and the view from an airplane window (Fig. 2). She soon embraced abstraction and focused on an array of quick stitches of unusual textures and colors. She believed that “to be a good designer one must also be a good collector,” and she acquired materials obsessively.15 Friends sent her fabrics and yarns from their travels and projects, and she collected everything from sidewalk finds and butcher twine to shoelaces and asbestos fibers. She used woven fabrics as her canvases and often stitched and talked as she sat surrounded by baskets of her lively yarns, strings, and threads.

Fig. 10. Back view of an embroidered jacket, c. 1935. Wool embroidery on wool; length approximately 19 inches. McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Karasz exhibited her work in the thriving gallery scene on 57th Street, first at Bonestell Gallery in 1947, then with the Bertha Schaefer Gallery for many years, beginning in 1948. Schaefer presented her work in both group and solo shows, versions of which traveled to dozens of venues across the country. She also regularly gave lectures and demonstrations, and in the summer of 1955 taught at Haystack Mountain School of Crafts in Maine, alongside three other luminaries in the field of textile design and art: Annie Albers, Lili Blumenau, and Jack Lenor Larsen. Larsen wrote: “Embroiderer Mariska Karasz advances independently in her own medium and, although her work often has the freshness of the primitives, she is part of the contemporary movement. . . . She thinks and works directly and spontaneously. . . .Forms, color balance and composition develop as she works.”16 Critics often discussed her wall hangings in terms similar to those they used for paintings. Some of her later works include found and handmade paper, and often look more like collages than embroideries though they retain the element of stitching (Fig. 7).

Fig. 11. Appliquéd dress, c. 1930. Silk; length approximately 53 1/4 inches. McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Karasz’s artistic career flourished throughout the 1950s and she even revised Adventures in Stitches in 1959, expanding the title and adding a new section called “More Adventures—Fewer Stitches.” She delighted in her medium and eagerly communicated her method. She wrote: “When I see someone show interest and curiosity about fabrics, threads and stitches, I have a deep feeling of satisfaction. I want to share with them the adventures and inward changes I have known.”17

Fig. 12. Gage Hill (the artist’s home in Brewster, New York), c. 1947. Cotton embroidery on cotton, 30 by 25 1/2 inches. McKelvey photograph, courtesy of the Georgia Museum of Art.

Fresh from a trip to Bolivia to collect materials and visit a friend, Karasz died in August 1960 after a brief illness. Throughout her life, she used thread to convey her charming, individual interpretation of modernism. With a sparkling sensitivity to the possibilities of color and texture, she created garments and artworks that reflected her love of the traditional needlework of her native country and the vibrant life of her adopted home.

1 List, c. 1929, collection of the artist’s family. For more information on Mariska Karasz, see: Ashley Callahan, Modern Threads: Fashion and Art by Mariska Karasz (Athens: Georgia Museum of Art, 2007) and Ashley Callahan, “Mariska Karasz’s Creative Embroidery,” Journal of Modern Craft, vol. 8, no. 2 (2015, special issue: Pathmakers: Women in Art, Craft and Design, Midcentury and Today), pp. 115–124. 2 “Shops for This and That,” New Yorker, December 21, 1929, p. 61. 3 For more, see Ashley Callahan, “The leafy modernism of Ilonka Karasz,” The Magazine ANTIQUES, (March/April 2018), cover and pp. 72–78. 4 Martha Dreiblatt, “Most Women Are Color Starved,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, January 13, 1929, p. 11; and “Costume Designers Make Fine Showing at the Cooper Union,” Women’s Wear Daily, May 29, 1918, p. 2. 5 Mariska Karasz, “On the Long Trail: Part I,” Art Life of the Studio Club of New York, November 1919, pp. 5, 10: and Mariska Karasz, “On the Long Trail: Part II,” ibid., December 1919) pp. 5, 10–11. Thanks to Renate Reiss for identifying Henriette Reiss as Karasz’s companion on this trip, in an email to me, March 1, 2010. 6 Karasz moved several times in the 1920s and 1930s, but always remained within a few blocks of Madison Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. 7 Alida Vreeland, “Hungarian Ideas Modernized,” Christian Science Monitor, December 18, 1929, p. 10. 8 “‘There Can Be as Much Expression in Clothes as There Is in Architecture,’” Vidette-Messenger (Valparaiso, Indiana), September 19, 1929, p. 7. 9 Receipt, c. 1929, collection of the artist’s family. 10 Transcript of conversation, possibly for radio, between Glenda Farrell, Mariska Karasz, Solveig Peterson, and Rozsika [Rosamond’s nickname] Peterson, undated (c. 1946), collection of the artist’s family. 11 “New Things Seen in the City Shops,” New York Times, November 20, 1938, p. 53. 12 Elisabeth Blondel, “Daughters of the Sun,” McCall’s, vol. 61 (May 1934), p. 133; and Kay Austin, “Little Dresses Appeal to Hearts of All Women,” New York World-Telegram, January 8, 1935, clipping, collection of the artist’s family. 13 Informal interview with Solveig Cox, June 8, 2004, Alexandria, Virginia, and informal interview with Rosamond Berg Bassett, March 16–17, 2006, New Canaan, Connecticut. “Mexican Embroideries for Girls’ Fashions in Custom-Made Group,” Women’s Wear Daily, March 6, 1941, p. 3. 14 Both of Karasz’s daughters became artists, Solveig a ceramist and Rosamond, a painter. 15 Mary Moore, “A Painter in Thread . . . Mariska Karasz,” Craft Horizons, vol. 9 (Winter 1949), p. 22. 16 Jack Lenor Larsen, “The Weaver as Artist,” ibid., vol. 15 (November–December 1955), p. 33. 17 Mariska Karasz, “Course in Creative Stitchery,” School Arts, vol. 54 (June 1955), p. 11.

ASHLEY CALLAHAN is an independent scholar based in Athens, Georgia. She recently served as guest co-curator of Crafting History: Textiles, Metals, and Ceramics at the University of Georgia, and is preparing an exhibition on scarf designer Frankie Welch for the Hargrett Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Georgia Libraries.