The story of the Preservation Society begins with the mission to rescue Hunter House (Fig. 1) and the question put to financier George Henry Warren Jr. after its purchase by his wife, Katherine Warren: “Well, you’ve got this house, now what are you going to do with it?”

In 1945, Newport stone carver John Howard Benson became alarmed that Hunter House—a rare surviving waterfront property with deep ties to Newport’s history—might be irretrievably lost. The residence was no longer needed by the Rhode Island Catholic Diocese, which had used it for a convent, and its survival was in jeopardy. So concerned was Benson that he and John Perkins Brown, whose Georgian Society also wished to save Hunter House, decided to speak with the Warrens. Benson and Brown traveled to the couple’s winter residence in New York City to warn, “the greatest eighteenth century house in Newport is going to be torn down, and the rooms . . . are going to be taken off to museums, and we have to do something to keep it.”

Benson and Brown worried that its unique Newport paneling and other details were in danger of being removed, stripping the house of its architectural treasures. The house’s great historic and architectural significance was well known to Newporters. It stands in Easton’s Point (today known as The Point), a distinguished neighborhood of pre- and post-Revolutionary residences that testifies to Newport’s golden age of commercial and maritime success. In the mid-1700s, Newport was a leading colonial port boasting more than five hundred ships annually in coastal and foreign trade. It was deeply engaged in the transatlantic Triangle Trade that shipped slaves, along with molasses and rum, between the West Indies, Newport, and the west coast of Africa. This reprehensible trade brought wealth to the city’s merchant elite while perpetuating slavery in the colonies. Rich merchants erected imposing dwellings commensurate with their status and filled them with the finest goods available from abroad or made by a rising generation of talented Newport artists.

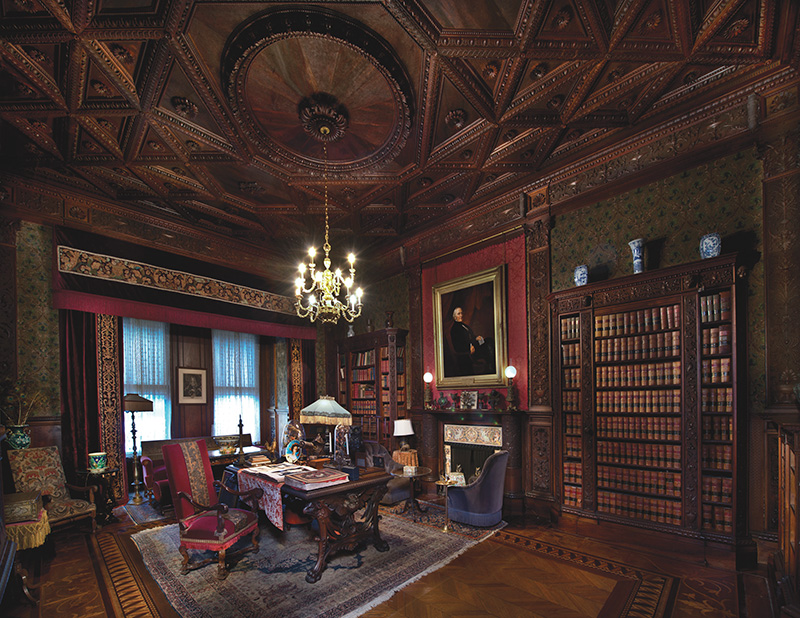

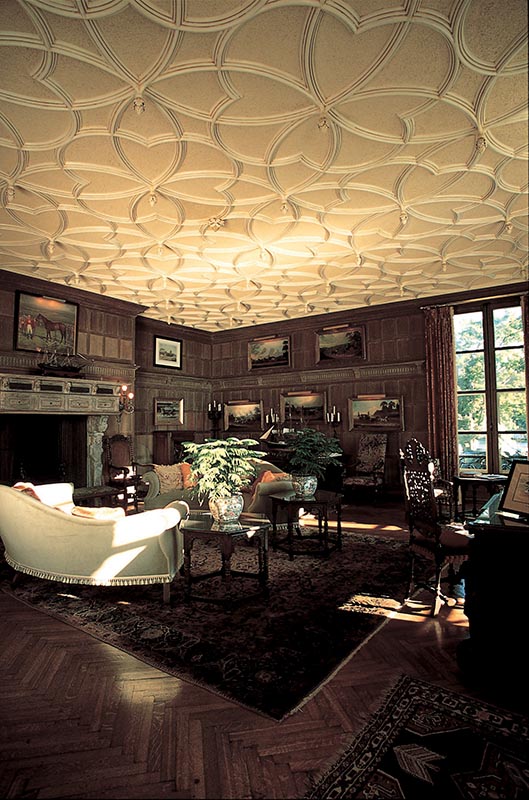

One of these great residences was Hunter House, formerly known as the Nichols-Wanton-Hunter House. The original house located on Washington Street was built beginning about 1748 for Deputy Governor Jonathan Nichols Jr., a merchant. He sold it in 1756 to Joseph Wanton Jr., a fellow merchant and deputy governor of the colony. The addition of a south wing and a second chimney, completed by Nichols around 1758, transformed the house into a wide and stately Georgian mansion with a large central hall that has four rooms on each side. Considerable expense was lavished on the interior, which included floor-toceiling paneled woodwork and Corinthian pilasters faux painted as marble (Figs. 2, 3), as well as a mahogany hall staircase with complex baluster turnings.

As a Tory sympathizer, Wanton was imprisoned and his property confiscated during the Revolutionary War. The residence was purchased in the early nineteenth century by United States Senator William Hunter, but after his death in 1849 the house fell on hard times. It was used as a boarding house and a convalescent home before its sale in 1916 to Dr. Horatio Storer. In 1918, St. Joseph’s Catholic Church received the house as a gift from Storer and his daughter Agnes for use as a convent. Fortunately, the apparent lack of funds for upkeep or modernization during these years meant that the house retained much of its original interior paneling. Years later, Mrs. Warren recalled that the church was willing to sell to an organization that would keep the house intact. In June 1945, a small group of concerned citizens–that included her husband–purchased the house in order to hold it until “such time as there is an organization that can take it over and can do something about it.” The next step was to form an organization that could support it. This was more than twenty years before the National Historic Preservation Act was passed, establishing a national advisory council and federal funding for preservation. Lacking these government resources, in 1945 the founders looked to initiatives like Colonial Williamsburg, Greenfield Village in Michigan, and Old Sturbridge Village in Massachusetts, among others. For the most part, these were outdoor museums formed around the notion of a town or village that could provide a historical experience. By contrast, since architectural gems abounded in Newport, all that was needed was to create an advocacy group. The timing seemed right.

Yet, for all its rich history and enormous potential, Newport was in a slump. The arrival of the Navy during World War I had saved it from free-fall when Gilded Age homes began to fall out of favor as summer residences. The income tax of 1913 and the Great Depression further dampened growth. Meanwhile, as society’s summer playgrounds changed and the mansions’ original owners aged, houses were sold or foreclosed upon and descendants balked at the cost of continued maintenance.

None of this deterred Mrs. Warren or her colleagues when, on August 9, 1945, they held their first official meeting at her home on 118 Mill Street and established the goal of raising funds to save Hunter House and pursue restoration strategies. In naming their new organization the Preservation Society of Newport County, the founders looked beyond the immediate needs of Hunter House to signal regional advocacy and outreach.

So then, what was to be done with Hunter House? The immediate concern was to raise money for its restoration and to occupy it for the sake of security. Some suggested using it as a model for building new homes or for restoring old structures. A tearoom was considered, while still other ideas included renting or selling the property for residential or nonprofit purposes. Throughout these discussions, board members undertook various fundraising activities, from fairs and auctions to bingo. Fortunately, these pressing financial concerns were allayed beginning in 1948 with the gracious assistance of Countess Széchenyi, née Gladys Vanderbilt, whose parents built The Breakers (Fig. 4). The countess allowed the Preservation Society to offer tours of the mansion’s first floor to paying visitors and keep the proceeds. This critical source of income enabled the board to plan its next step: engaging the country’s leading experts in historic preservation for advice on restoring Hunter House.

Drawing on the advice of Colonial Williamsburg expert Kenneth Chorley, board members became imbued with the notion that Newport could become a major center for tourism if they could leverage the city’s three centuries of architectural treasures through preservation. This line of thinking led them to consider what other properties might serve such a mission. Over time, new rescue opportunities presented themselves. In July 1962, The Elms, the neoclassical home on Bellevue Avenue built by Pennsylvania magnate Edward Julius Berwind, was slated for demolition. The mansion was of historical significance because of its 1898–1901 design by Horace Trumbauer, who represented a new generation of American architects working in the grand manner (Fig. 6). Its magnificent Sunken Garden in the Beaux Arts style, established between 1902 and 1914, is thought to be the work of Julian Abele, an African American architect hired by Trumbauer in 1906 (Fig. 5); Abele became chief designer for Trumbauer’s architectural firm in 1908.

The Preservation Society moved quickly to acquire The Elms with funds offered by twenty-seven donors, but it was unable to secure the furnishings, which had been sold at auction. Despite this setback, board members set to work securing a combination of museum and private loans. Members also combed their own residences for appropriate items to fill out the house for visitors. The house opened to the public within a month of its acquisition. It was the second luxurious Gilded Age residence after The Breakers to be administered by the Preservation Society.

In 1963, scarcely a year later, Marble House, a Bellevue Avenue mansion in the Louis XIV style, was given to the Preservation Society (Fig. 10). This summer residence, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, also architect of The Breakers and Ochre Court, was created in the early 1890s for William Kissam Vanderbilt and his wife, Alva; by the 1930s it had been purchased by Frederick H. Prince of Chicago. The gift of Marble House, its furnishings (Fig. 8), and the Chinese Tea House (Fig. 9) on the property was arranged by Harold S. Vanderbilt, son of the original owner, who was a yachtsman and successful America’s Cup defender.

In its desire to protect historic Newport architecture, for a time the Preservation Society acquired, retained, and resold properties using established legal procedures. The Preservation Society held some properties, but others were handled by a separate corporation called Restorations, Inc. The intent was to acquire at-risk properties and hold them until preservation-minded individuals could step in to purchase and restore them. In this manner, a number of seventeenth- and eighteenthcentury structures with historic and architectural merit were saved for others to protect and own.

The Preservation Society’s activities in this arena ceased in the 1960s as grassroots organizations like Operation Clapboard and the Oldport Association took up this role, together acquiring about sixty properties for preservation. In 1968, the Newport Restoration Foundation was founded by Doris Duke to carry on the work of preserving early houses, and ultimately purchased more than eighty homes. These efforts by fellow organizations freed the Preservation Society to take on other challenges.

One of these was its search for working space. As the Preservation Society’s staff grew, it moved several times, each time seeking a location that could also strengthen its identity as a protector of Newport’s historic and architectural treasures. In 1947, it planned to turn the Pitt’s Head Tavern on Charles Street, which it had received from the Georgian Society, into its permanent headquarters. In the eighteenth century, the gambrel-style house had been turned into a tavern honoring British statesman William Pitt for supporting repeal of the Stamp Act. The tavern was occupied by Preservation Society staff in 1953 after some renovations, but full restoration ceased around 1959, when offices in the handsome Peter Harrison– designed Brick Market (1772) on Thames Street became available to rent. This change of heart may have been due to space considerations or the fact that the Brick Market location was more desirable. Whatever the reason, the Pitt’s Head Tavern was set aside for sale to a preservation-minded private owner.

This pattern of occupying historic structures has continued to the present day at the Preservation Society’s current headquarters, a Romanesque revival mansion constructed in 1888 as a summer residence for William H. Osgood of New York. The mansion was purchased by Herbert C. Pell Jr. heir to the Lorillard tobacco fortune, in 1921. Pell served one term in the US House of Representatives from New York, and was later appointed as US ambassador to Portugal by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. His son, Claiborne Pell, went on to represent Rhode Island in the United States Senate from 1961 to 1996.

Some properties helped the Preservation Society to clarify its mission. The Matthew Calbraith Perry House on Walnut Street was planned as a museum dedicated to the national hero who ended Japan’s policy of isolation in 1853–1854, leading Japan to establish diplomatic relations with the United States and open itself to trade with the West. Perry’s childhood home in Newport was given to the Preservation Society in 1966 by Mrs. David Van Pelt and plans were made for turning it into a museum of “Perryana.” Blueprints were drawn up for its restoration, but momentum cooled in 1968 when costs proved to be higher than expected. In the end, the opportunity to acquire another illustrious Gilded Age property may have prompted the board to reconsider its commitment to the Perry House and clarify its mission.

In 1969, Chateau-sur-Mer became available to purchase. This stately 1852 Italianate residence had been updated in the 1870s with major renovations in the French chateau style by Richard Morris Hunt (Fig. 12). In 1900, a ladies’ reception area was updated in the neoclassical manner by Ogden Codman Jr. The house had been owned by Preservation Society board member Edith Wetmore and her sister Maude, but its acquisition would require a purchase. Chateau-sur-Mer was highly desirable but its purchase, restoration, and upkeep presented a financial challenge. The Perry House, by contrast, was of historic interest because of its owner, but it was not particularly handsome or architecturally distinguished, nor did its narrative fit neatly into the history of Newport.

With the acquisition of The Elms, Marble House, and Chateau-sur-Mer in the 1960s, the Preservation Society demonstrated its desire to expand beyond the colonial world of Hunter House to the summer cot tages of the Gilded Age. These mansions—which had been dismissed as early as 1906 as “white elephants” by author Henry James—were by the late 1960s demonstrating their growing popularity with a soaring attendance at The Breakers, which surpassed ninety thousand in 1970.

Perhaps for this reason, the Preservation Society added three more properties in short succession. Rosecliff, the palatial Bellevue Avenue residence designed by Stanford White, joined the Preservation Society in 1971, a gift of Mr. and Mrs. J. Edgar Monroe (Figs. 13-15). Less glamorous but of historical and horticultural interest was a topiary garden and nineteenth-century gentleman’s estate in Portsmouth called Green Animals, which was bequeathed by board member Alice Brayton in 1972 (Fig. 16). Also, in 1972 Mrs. Anthony B. Rives bequeathed Kingscote, a rare example of a Gothic revival house and landscape setting preserved intact with original family collections (Fig. 17). By this date, the board and staff were fully absorbed with these new properties, and the future seemed bright. Later that year the Preservation Society purchased The Breakers from its heirs, welcoming Newport’s most celebrated property into the fold and sealing the Society’s identity as a steward of Gilded Age architecture. Now all it had to do was protect the houses from the elements, manage the increasing flow of visitors, and conduct first-rate restorations—a very tall order.

This article is excerpted and adapted from The Newport Experience: Sustaining Historic Preservation into the 21st Century. All notes and references are available in the book, written by Jeannine Falino, edited by Terry Dickinson et al., and published in 2020 by the Preservation Society of Newport County in association with Scala Arts Publishers, Inc.