This view of Rokeby shows its columned piazza, tower, and mansard roof—added in the 1850s by the Astors to the original 1811 house.

Rokeby stands out. Very few places I have visited have an equivalent halo of unparalleled character surrounding the history, design, and activities associated with this private home. The same family has owned this property for eleven generations since 1688. It is a source of considerable pride for its members, who are descendants of the original owners and still reside in their ancestral home.

When Margaret Livingston Chanler Aldrich passed away in 1963, Rokeby, which had been left to her and nine siblings by her mother in 1875, was placed in a trust for the three children of her son, who had predeceased her. Today, Richard “Ricky” Aldrich and his wife, Ania, live at Rokeby full-time; John Winthrop “Wint” Aldrich and his wife, Tracie, part-time; and Rosalind Aldrich Michahelles, some of the time. Margaret imprinted on her grandchildren the primary importance of invested ownership and care of Rokeby.

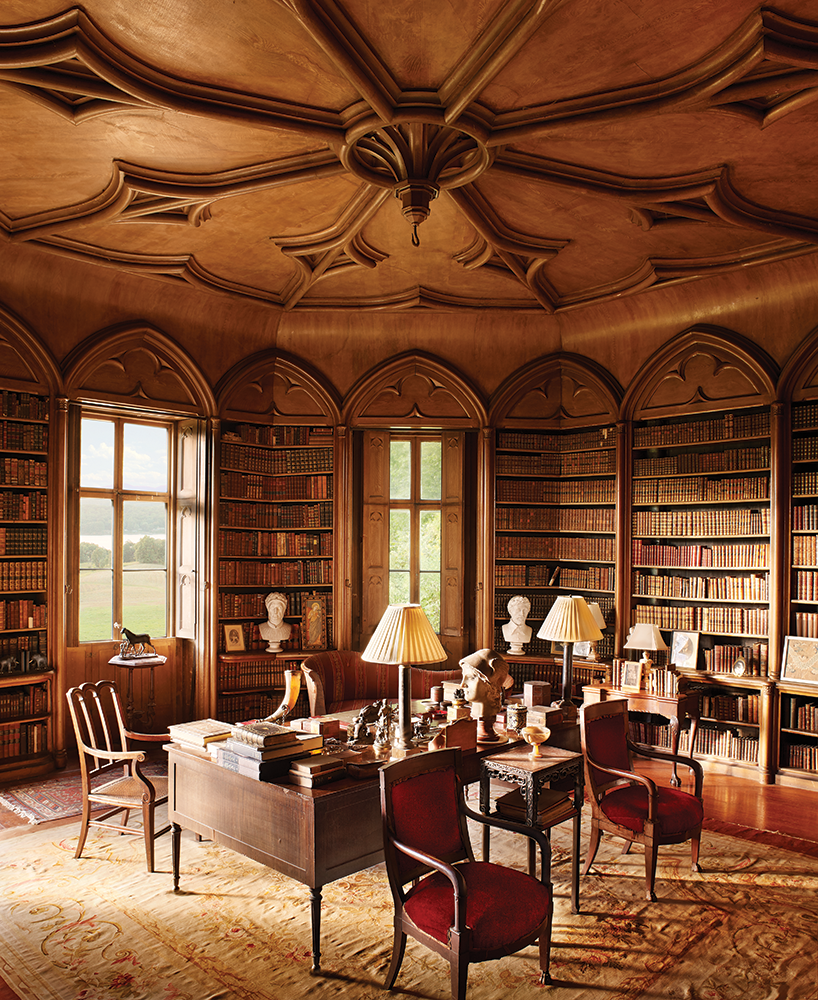

The 1858 octagonal Gothic revival library, with a faux bois–painted plaster ceiling, was the favorite retreat of William Backhouse Astor Sr. (1792–1875). The marble sculpture of the head of Hermes on the desk was once the centerpiece of Elizabeth and John Jay Chapman’s library at Sylvania in Barrytown, New York.

In 1790 John Armstrong Jr. borrowed funds from Robert “the Chancellor” Livingston, the brother of his wife, Alida Livingston, to build the Meadows, on the current site of Bard College’s Fisher Center for the Performing Arts in Annandale-on-Hudson. An early real estate speculator, Armstrong sold the Meadows and built Mill Hill in 1795, the location of the future Blithewood estate, also now on Bard’s campus. Rokeby was Armstrong’s third house in the area, and shared the same carpenter as those two extraordinary Federal homes, Warner Richards.

A 1798 letter from Armstrong, playing the real estate seducer, to the representative of his friend Rufus King describes available property in Red Hook as follows: “a farm superior to any I have mentioned. It contains 420 acres, 100 of which is meadowland—220 arable, and the remainder, woods . . . . There are upon it two situations for building, somewhat different in character, but equally desirable. The one is on the River and commands a long reach north and south. The other is on still higher ground, and farther removed from water; a fine view of the River.” The second location is where Armstrong eventually built Rokeby in 1811.

Armstrong is known for his celebrated unsigned letters that were privately circulated among the officers of the Continental Army stationed at Newburgh. The letters were intended to stir up rebellion against Congress by the soldiers, who had not received compensation for their services. Although the letters were surreptitiously published as the Newburgh Address in 1783 with provocative intentions, George Washington later exonerated Armstrong of any wrongdoing.

A 1925 portrait of Elizabeth Winthrop Emmet Morgan (1897–1934) by De Glehn hangs in the master bedroom. The Zuber & Cie. pheasant wallpaper was installed by White in 1894.

Following the war, after a brief stay across the Hudson River in Kingston for his children’s education, Armstrong moved to Washington, DC, when he was elected US senator from New York in 1800. Thomas Jefferson appointed him minister plenipotentiary to France in 1804, directly following in the footsteps of his brother-in-law, the Chancellor, who had previously held the post. Armstrong assumed his position in the court of Napoleon, who was at the height of his power. The couple arrived in Paris, settling in at 100 Rue de Vaugirard, in time to participate in the coronation of Napoleon and Josephine at Nôtre-Dame de Paris. Armstrong was selected on November 16, 1804 (twenty-sixth Brumaire, year thirteen, of the French Republican calendar) by the artist Jacques-Louis David to pose for his monumental painting of the coronation. “Alida enjoyed visiting the great artist’s studio on the two occasions her husband was being painted,” wrote William Astor Chanler Jr. in 1890, in a lengthy typed manuscript about his ancestor. Alida “was presented to Josephine as well as Napoleon’s sisters, the Queen of Naples, and Pauline Bonaparte to complete her initiation into court.” Well versed in posing for famous artists, Armstrong later had his portrait painted by Rembrandt Peale when the artist visited Paris in 1808.

The entrance hall was plastered and painted in 2012 to resemble the original marble ashlar decoration. The seventeenth-century Flemish tapestry came from Laura Astor Delano’s town house in Manhattan.

While approaching the end of his stay in Paris, Armstrong started a search for a future home in the Hudson River valley. Alida turned to her sister Margaret Tillotson for help and persuaded her husband that upon his return to America in 1810, his “future lay on the North River,” the name in the early nineteenth century for the Hudson. Six years of intrigue and deception at court more than satisfied any diplomatic ambitions he once had; Armstrong longed to dwell again in the bucolic valley of the Hudson among relatives and friends.

After traveling back to America, the couple lived at Clermont while building their house, which Armstrong nanced through a loan from the Manhattan Bank (a predecessor to today’s JP Morgan Chase and Company). He was obliged to offer financial settlements to the Palatine leaseholders of the Sipperly, Mohr, Finehout, Feller, and Benner farms—who had cultivated the land since 1712—in order to consolidate a respectable amount of property. The dwelling he constructed had six bedrooms and a steeply hipped roof crowned with a pyramidal monitor. The one-hour calèche ride from Clermont to the construction site to oversee the work was bumpy, cold, and dusty.

The Armstrongs named the property La Bergerie (the sheepfold), reflecting the French tradition of surrounding homes with pastoral views, and specifically in recognition of the flock of merino sheep Napoleon had sent back to America with the family as a gift. Merinos fared less well in the cold northern climate than in Corsica and Spain, so Alida wrote that she organized “genteel ladies [who] devoted as much time knitting sweaters for Merino lambs as for their children.”

The drawing room’s French windows face the Hudson. Above a bronze bust of Robert Chanler (1872–1930), sculpted by Séraphin Soudbinine (1867–1944) in 1920, hangs a portrait of Margaret Livingston Chanler (later Aldrich; 1870– 1963), painted by William Sergeant Kendall (1869– 1938) in 1900, which was featured on the cover of the January 1903 issue of Town & Country.

James Madison had appointed Armstrong secretary of war in 1813 to assist in the ongoing War of 1812. Following the calamities wrought by the conflict, the tides turned against Armstrong politically when the White House was burned, as he was considered accountable for leaving the capital poorly defended.

In 1818 the Armstrongs’ daughter Margaret married William Backhouse Astor Sr., a son of John Jacob Astor, then considered the wealthiest man in America. John Jacob had followed his brother to England from Germany in 1779, and the two produced musical instruments there. In 1783 he sailed to America to sell his flutes and clarinets. Traveling up the Hudson River, he made the decision to accept fur pelts as payment, and eventually opened a fur business on the side. As a result of his efforts in pushing his trusted agents to further penetrate the Indian Territories, the American Fur Company was established and became prosperous. Astor went on to finance much of the War of 1812 with the proceeds from his mink and beaver pelts as well as his real estate earnings. While working for his father’s business ventures, William Backhouse Astor increased the family’s holdings from an estimated twenty million dollars in 1848 to more than one hundred million dollars in 1875.

Margaret Armstrong Astor’s passions were horticulture and the literature of the romantic period. Following her honeymoon with William Backhouse Astor, in 1818, she asked her father to change the name of the farm to Rokeby, after reading the recently published poem of the same name by Sir Walter Scott. She found similarities between a glen on the property known as Devil’s Gorge and the landscape in Scott’s poem, which describes Rokeby Park near Greta Bridge in County Durham, England. Her fond associations with her family home begged a more romantic name.

John Jacob Astor offered Armstrong fifty thousand dollars for Rokeby in 1835 to assuage Armstrong’s concerns about financially providing for his children upon his death. Following the sale, Armstrong moved to his son Henry Beekman Armstrong’s house, Wayside, in the village of Red Hook, to live out his years until he died, in 1843.

The circular radiator in the dining room was included in the renovations made by Stanford White (1853–1906) in 1894. Robert Chanler’s 1912 panel Death of the White Hart is flanked by portraits of Margaret Chanler Aldrich and Richard Aldrich (1863–1937), painted by Ellen Emmet Rand (1875–1941) in the 1930s.

A path on the property called the Poets’ Walk was embellished by the German landscape gardener Hans Jacob Ehlers in 1849. William Backhouse Astor’s subsequent improvements to the house in the 1850s included the polygonal tower on the west side containing a Gothic revival library that became his favorite refuge. The house was also re-stuccoed to disguise the underlying materials, and an eighty-foot-long porch was added.

The Astors had six surviving children who were brought up at Rokeby: John Jacob III, Laura, Alida, William Backhouse Jr., Henry, and Emily. The eldest child, Emily, married Samuel Ward Jr. in 1838. Their daughter, Margaret “Maddie” Ward, inherited Rokeby in 1875. Samuel Ward Jr. had grown up in Manhattan at Corner House, which was designed by Isaac Pearson and Alexander Jackson Davis at the intersection of Bond Street and Broadway. (The house included one of the first private art galleries in the city. His father commissioned Thomas Cole’s painting series The Voyage of Life for this space, but died before its completion.) The location of the Wards’ house was part of an established neighborhood in the 1830s that included Lafayette Place, Bond Street, and Broadway, and was where Emily Astor had also spent her childhood.

Maddie was brought up by her grandparents after her mother died while giving birth to a son in 1841. Her father was thought to be, even for this family, too eccentric and unfit to parent following his swift remarriage to Medora Grymes. When William Backhouse Astor Sr. died, he left Rokeby to Maddie, who had wed John Winthrop Chanler, a New York State congressman and sachem of Tammany Hall. They had ten surviving children, born between 1862 and 1874, who inherited the property as tenants in common in 1875, following the premature death of their mother, who had caught a chill when returning from her grandfather’s funeral. Her demise was followed by the passing of their father in 1877.

Reception room looking south, with the French window opening onto the piazza and the south lawn beyond. The portrait is of Laura Astor (later Delano; 1824–1902) and her sister Mary Alida (later Carey; 1823–1881), by William West (1801–1861), c. 1845; a plaster bust of Edward Livingston (1764 –1836) by Robert Ball Hughes (1806–1868), c. 1830, stands on a piano made by Astor & Co. in London, c. 1810.

This generation became known as the “Amazing Chanlers.” Reduced by early deaths to eight, they came into their inheritance once they reached the age of twenty-one—“share and share alike,” per their mother’s will. The rambunctious Chanlers lived lavishly in an atmosphere replete with reminders of their Livingston ancestry. After their guardians shuttered the family’s Manhattan residence at 192 Madison Avenue, on the site that became B. Altman & Co., they grew up at Rokeby with only periodic oversight as their guardians remained in the city. Meals were observed to be combative in the extreme as each Chanler volleyed for verbal dominance at the table. Family biographer Lately Thomas describes the commonplace scenes as “monumental disputes and fantastic reconciliations.”

The eldest sibling, John “Archie” Armstrong Chanler, married writer Amélie Rives, the “Siren of Virginia,” whose temperament was described by the press as “molten lava.” Following her success with the novel The Quick or the Dead?, Archie was confined in Bloomingdale Insane Asylum in White Plains by his brothers because of his erratic behavior.

In 1916 Winthrop Astor Chanler married Margaret “Daisy” Terry, who had grown up in the Odescalchi Palace in Rome. Their daughter Laura married Lawrence White, the son of architect and family friend Stanford White.

Elizabeth Chanler spent years wearing back braces before breaking free from her chrysalis to emerge as a spectacular beauty immortalized by John Singer Sargent in 1893 while she was visiting London. Her sister Margaret overheard Sargent explaining to Elizabeth during one of the sittings, “Miss Chanler, I have painted you la penserosa. I should like to begin all over again and paint you l’allegra.” While in London, she failed to curtsey while being presented to Queen Victoria, causing a scandal. Known as “Queen Bess” by her siblings, she married John Jay Chapman, the essayist, and moved to the estate Edgewater, in Barrytown, New York, not far from Rokeby.

Stanford White’s 1894 design combined two parlors to create the grand drawing room with its Greek key crown molding. He also selected the wallpaper for the room, where Laura Astor married Franklin Hughes Delano (1813– 1893) in 1844.

William Astor Chanler became a congressman and African safari explorer. Upon dropping out of Harvard University in 1888, he embarked on a dhow from Zanzibar to Kenya, and proceeded up the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro with 120 porters. On a subsequent expedition he discovered what became known as Chanler’s Falls, in present-day Kenya. He was described by his sister-in-law Margaret Terry Chanler as “the most promising of the four brothers, he was a brilliant creature, dark-eyed, romantic-looking, with a great personal charm and flawless courage.”

Lewis Stuyvesant Chanler served as lieutenant governor of New York, and was nominated as the Democratic candidate for governor in 1908. He married Alice Chamberlain from the estate Maizeland, in Red Hook, and later wed Julia Olin, who had grown up at the Livingston estate Glenburn.

The walls of the Crow Room were painted by Robert Chanler in 1900 with a view of Overlook Mountain and the Catskill Mountains.

Margaret Livingston Chanler became a nurse during the Spanish-American War and an activist in the women’s suffrage movement. She wrote of participating in twelve political campaigns on behalf of three brothers. Margaret married Richard Aldrich, the music critic for the New York Times, in 1906, when she was thirty-five years old, after obtaining sole interest of Rokeby from her siblings.

The stair rail—which retains a fragment of its original red velvet covering—was installed by Stanford White (1853–1906), as was the laylight that illuminates the hall. The portrait on the left is of Alida Chanler Emmet (1873–1969), painted in 1915 by Wilfred Gabriel De Glehn (1870–1951). On the right is a portrait of her husband, Christopher Temple Emmet (1868–1957), with one of their sons, painted by his sister Lydia Field Emmet (1866–1952).

Robert Winthrop Chanler became an accomplished artist. His work is on view at Rokeby, and he created a surreal fireplace, composed of bronze and plaster flames, in the studio of Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney on Eighth Street in Manhattan. He hosted some of the most riotous parties in New York City, and was the godfather of fashion legend Diana Vreeland. In an article about Robert in the New York Sun in 1912, his home and studio were described in detail. The studio, called “The House of Fantasy,” was full of live spider monkeys, toucans, ravens, rattlesnakes, and a “guyneet cat with a head like a leopard and nostrils like a weasel.”

Robert’s first wife was Julia Chamberlain, the sister of his brother Lewis’s first wife, Alice. He hired the architectural firm Warren & Wetmore to design a French Provincial home, but Julia had no desire to live in Red Hook. Robert’s second wife was Natalina “Lina” Cavalieri, one of the most famous opera singers and beauties of the time. She orchestrated an advantageous prenuptial agreement with Robert, then quickly divorced him. Upon hearing of the divorce, his brother Archie famously sent him a cable that read, “Who’s loony now?”—payback for the time Archie had spent in an insane asylum after his brothers had him committed.

The youngest sibling, Alida, married Temple Emmet and lived at The Mallows, designed by Charles A. Platt, near Stony Brook, Long Island. She died in 1969 at age ninety-seven, the last surviving member of the celebrated “Four Hundred”—the name coined for her cousin Ward McAllister’s list of chosen members of society.

Stanford White, being a close friend of the Chanler family, embarked on sprucing up Rokeby in 1894. White pledged to Margaret that he would “cut about a dozen doors, add some bathrooms, throw a north gable where the attic is, and you will find living here much easier.” Armed with a budget of ten thousand dollars, he helped Margaret, who was then twenty-four years old, address inherent problems with heating, plumbing, and electricity. Among the improvements were a laylight above the central block of the house, a staircase that included two discreet passageways for staff, and the combining of two parlors on the west side of the house into a grand drawing room. Still intact in this room is the wallpaper chosen by White, as well as his Greek key molding.

The commanding view from the fifth floor of Rokeby’s tower takes in the property’s lawn, the Hudson River, and the Catskill Mountains in the distance.

Margaret held White to the agreed-upon budget even though the final bill for the alterations came to much more. Modifications to the exterior of the house were implemented later by Margaret, who engaged her brother-in-law, the architect Chester Holmes Aldrich, of the firm Delano & Aldrich. Olmsted Brothers was enlisted in 1911 to enhance the earlier 1840s landscape design by Hans Jacob Ehlers.

Today, Shoving Leopard Farm—a cut-flower business run by Marina, Rosalind Aldrich Michahelles’s daughter—maintains Rokeby’s fertile land, long ago planted with corn by the Lenni-Lenape tribe native to the area. Marina’s sister, Sophia, runs a workshop on the property specializing in the production of the puppets that populate Rhinebeck’s annual winter Sinterklass festivities, as well as New York City’s Halloween parade.

“It is hugely gratifying to us that with good luck and hard work, Rokeby is in good shape—the future looks promising,” says Wint Aldrich. When considered along with the following quotation from his grandmother Margaret Chanler Aldrich, the stage is set for the present: “Well into this generation of my children, nieces, and nephews, as well as our grandchildren, Rokeby continues to know ‘share and share alike.’”

This article is excerpted and adapted from Life Along the Hudson: The Historic Country Estates of the Livingston Family, written and photographed by Pieter Estersohn and published by Rizzoli ($85).

PIETER ESTERSOHN is a leading photographer of architecture and interiors. His work regularly appears in such magazines as Architectural Digest, and he is the author of Kentucky: Historic Houses and Horse Farms of Bluegrass Country (Monacelli Press, 2014). Estersohn serves on the Historic Red Hook Advisory Council and the board of Friends of Clermont, and belongs to the Edgewood Club of Tivoli, New York, founded in the 1880s by the original owners of many of the homes featured in his new book.