The first work I ever saw by Rosie Lee Tompkins was in an exhibition titled Showing Up, at the Richmond Art Center, in a town just north of Berkeley, California. It was 1996, and the exhibition was composed of black-and-white African American quilts from the collection of Eli Leon. Tompkins’s work was small, about four feet by four feet, but the pattern it contained might as well have been the entire Milky Way. It expanded and contracted, spun and whirled, and it seemed to possess a strange, unfathomable energy. At the time, I knew nothing about African-American quilts, Eli Leon, or Tompkins herself. I walked through the exhibition, which included works by two dozen different artists, but it was this single work by Tompkins that caught my eye and compelled me to find Leon and ask him who on earth Tompkins was and whether he had any other examples of her work. “You like that piece?” he said on the phone. “You should see what she does with color!”

Eli invited me to come to his home to see more of her works. His home was close to mine, just over the Berkeley-Oakland border, in a neighborhood of small, Craftsman-style homes. Eli’s house was singularly nondescript. From the exterior, it appeared somewhat neglected, surrounded by weeds and distinctly in need of a fresh coat of paint. “Doorbells don’t work,” said a little sign taped next to the door, so I knocked. After a couple minutes, I heard several locks being opened from the inside. I’d assumed that a collector of African-American quilts who lived in Oakland would be black. On the phone, his voice could have been anyone’s; it was perhaps a little high-pitched. To my surprise, Eli was a white guy.

We entered the house, and when Eli closed the door behind me, we were cast into darkness. The living room, if you could call it that, was packed floor to ceiling with neatly folded quilts. No light penetrated the stuffy interior. He led me into the kitchen, which felt a bit more like a conventional domestic space except that every object on every shelf was made of green plastic.

It didn’t take long for Eli and me to make the connection that we’d gone to the same college, Reed, though he was there at least a decade before me. Eli told me that he had been a psychologist.

The clutter I’d seen in Eli’s house was nothing compared to what he was about to show me. He opened a rickety door, switched on a light, and asked me to follow him downstairs. Beneath the ramshackle house was a brightly lit, climate-controlled storage space crammed full with what I now realize must have been literally thousands of quilts. There wasn’t enough room for two people to pass one another in the narrow spaces between the shelves. Eli climbed a ladder and selected a couple quilts from the topmost shelf. We went back upstairs into the kitchen, where he had a small footstool ready. He climbed up with one of the quilts in hand and asked me to pass him a pushpin. Slowly, he hung the quilt across the opening between the kitchen and the living room. Section by section of the heavy pieced velvet fell until the whole breathtaking composition was visible. It was a Rosie Lee Tompkins.

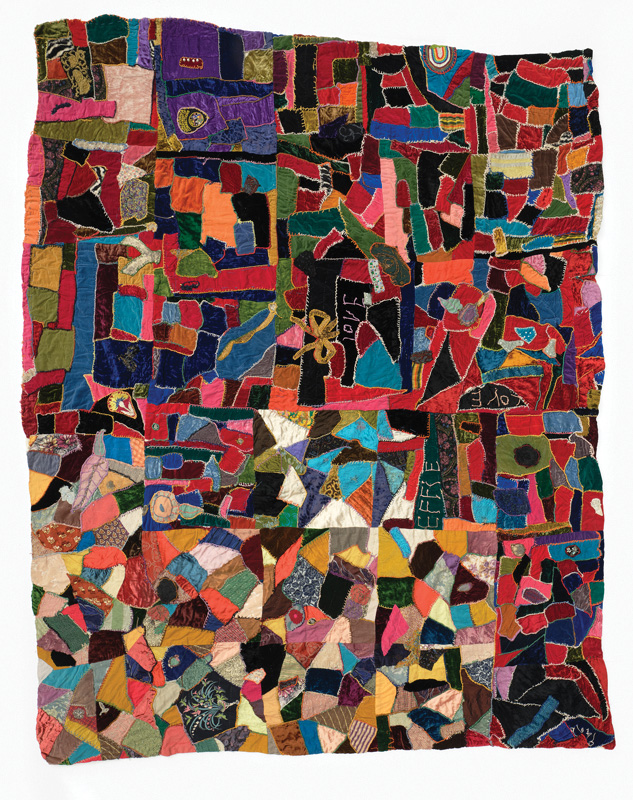

Eli was probably talking, explaining one of his theories about the African origin of the patterns and technique. But I was lost in the work. I was still a fairly young curator, but I’d seen my share of art, abstract painting in particular. This was in a different league. It was partly the combination of color and texture. The velvet added an astonishing sensuousness and depth to the essentially flat surface. Most incredible, though, was the amazing feeling of organization mixed with spontaneity. I didn’t know the names of the patterns and forms yet, but I was looking at, marveling at, radiant medallions enclosing irregular areas of color like sacred gardens, grids of infinitesimal fabric mosaic, half-squares of countless sizes spreading like fractals across the surface. And, despite the seeming chaos and disorder, the whole thing held together, miraculously.

Rosie Lee Tompkins didn’t study at art school. If she studied with anyone, it was her mother. And what difference should this make? None, as far as I’m concerned. We learn where we learn. She believed, I later discovered, that God had answered her prayers and given her the creative power of quilting. Eli believed that she’d inherited her skills—culturally, socially, and perhaps unconsciously—from her African ancestors.

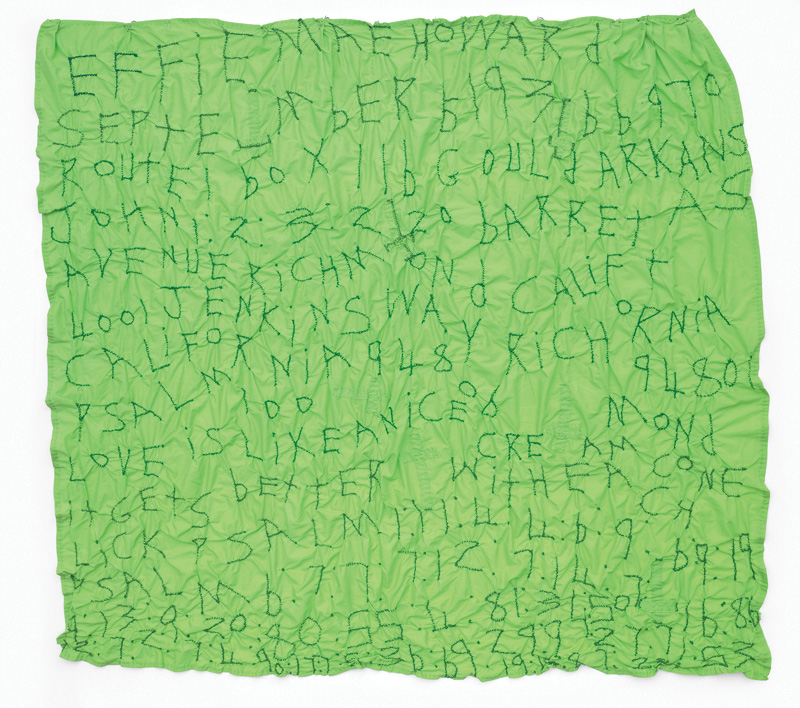

A year or so later, when I was organizing an exhibition of Tompkins’s work, Eli agreed to ask Tompkins if she would meet me. She reluctantly agreed. We drove out to her place in Richmond. It was even smaller than Eli’s. At the door, she told Eli that she’d changed her mind. She didn’t want to meet me after all. But, somehow, he convinced her. I even got a hug at the door. Inside it was neat and light. Her quilts covered the walls, tables, couches, and chairs. There were stacks of books on the coffee table. I don’t remember specifically what the books were, but they were definitely art books—Old Masters, I think. She didn’t talk much, and when she did, she spoke quietly. Unfortunately, I don’t remember what we spoke about, and I didn’t record the meeting. She was such a private person—in fact, she kept her real name, Effie Mae Howard, a secret. For many years, it was widely rumored that she was a fiction invented by Eli. Some people were so adamant about it that I sometimes doubted my own experience, wondering if it had been a dream.

It was a shock and a surprise to learn, in early 2018, that Eli had left his entire collection to the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. I had known him for years, and we shared a passion for the quilts, but it was his singular focus and not mine. I’d organized a solo exhibition of Tompkins’s work at BAMPFA in 1997 and included several of her pieces in the 2002 Whitney Biennial exhibition, as well as in the opening exhibition at BAMPFA’s new building in downtown Berkeley. But I was busy and didn’t have as much time as I would have liked to help him think through how to make sure the quilts went to the right places after he was gone. What he would have really loved would have been to see them spread across the country, among the leading art museums of the United States, embraced as art, and exhibited alongside the great artists of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. I helped him make some initial contacts, but nothing panned out. Then, he got the news that he was suffering from a degenerative mental condition. He knew he didn’t have enough time left to fulfill his dream.

The art world still has some work to do before it is able to accept that art by women who learned to quilt from their mothers and friends can be of just as much value as paintings made by Yale MFA grads. But it will get there, and maybe sooner than we thought. This year, BAMPFA will help to advance this goal by mounting a major retrospective of Rosie Lee Tompkins—drawing from the more than five hundred Tompkins quilts in Eli’s collection—which will make the case that exceptional works by artists of nontraditional backgrounds deserve to be included in any serious assessment of the American art historical canon.

Rosie Lee Tompkins: A Retrospective is on view at the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive from February 19 to July 19.

LAWRENCE RINDER is director and chief curator of the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive. He has previously held positions at the Museum of Modern Art, the Walker Art Center, and the Whitney Museum of American Art, where he was chief curator of the 2002 Biennial.