The painter Alethea Hill Platt spent the first half of her life in comfortable obscurity, painting for her own pleasure in a Greenwich Village town house. But in the 1890s, she was forced out of her home and scrambled for income. She nimbly reinvented herself as a fixture on the Manhattan art scene.

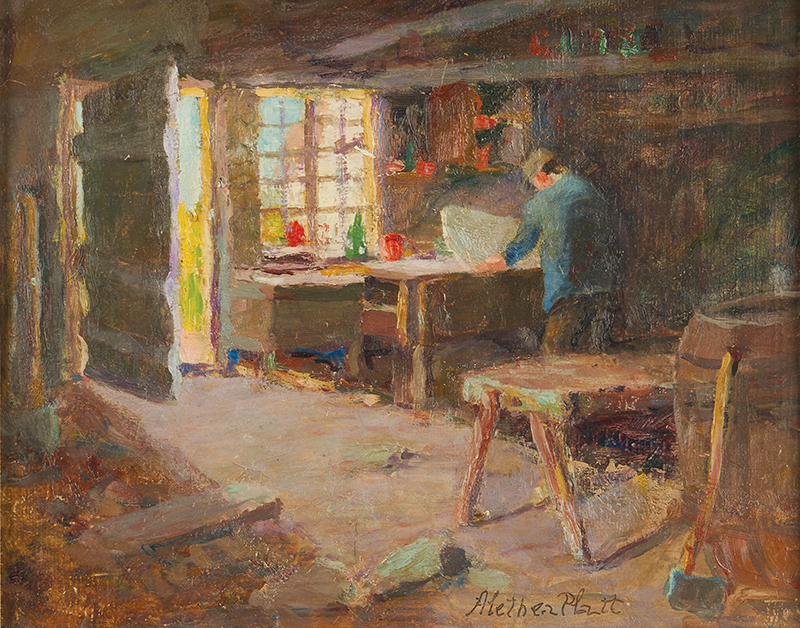

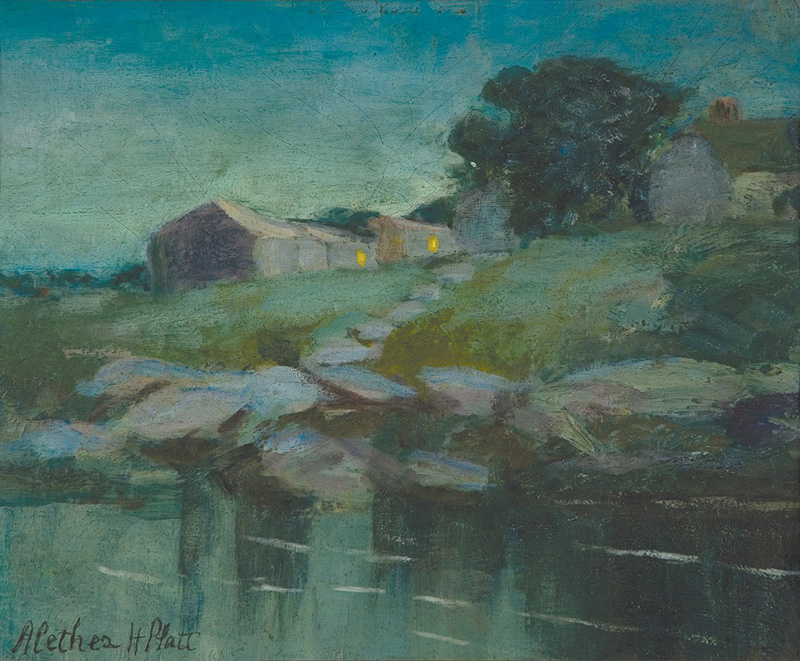

She joined forces with women painters organizing exhibitions nationwide. She won acclaim for a kind of Ashcan school take on rural scenery in Europe and the United States, depicting fishermen, farmers, and craftspeople laboring in dimly lit cabins or outdoors by moonlight. The New York Times lauded her canvases’ “quality of serenity, even a kind of nobility,”1 and American Art News placed her “in the ranks of America’s leading women painters.”2 She did not seek fame, however. She gave few interviews or lectures. She apparently published no writings. A dozen pages of her correspondence have surfaced so far in archives. Some moments in her life are vividly recorded only because she endured interrogations in Manhattan courtrooms.

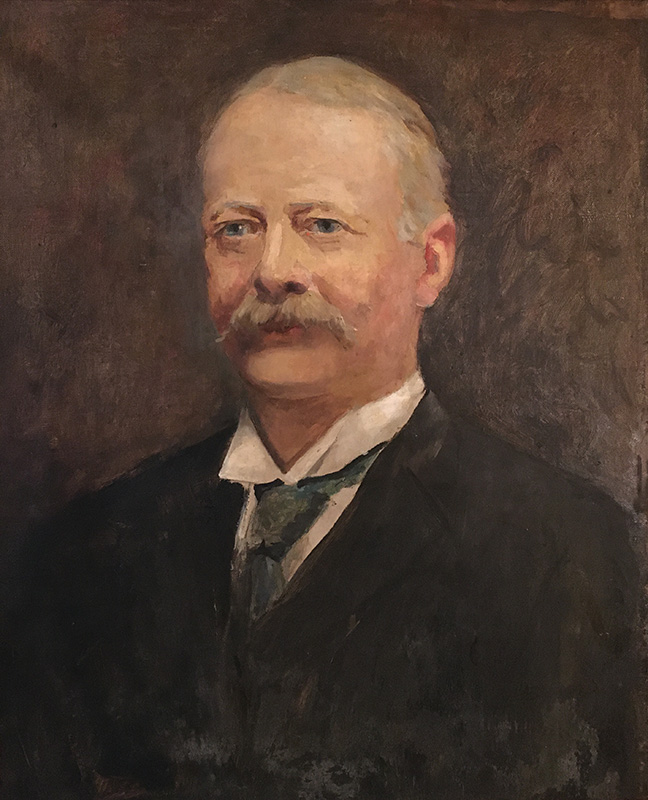

Platt was born in Scarsdale, New York, one of at least nine children of Lewis Canfield Platt, a judge and politician, and Laura Sherbrook Popham. The family descended from Revolutionary War heroes, including Declaration of Independence signers. Alethea, as a child, “showed a preference for drawing pictures beyond all other interests,”3 while her three brothers ventured into real estate, politics, and law. A family friend, the banking and real estate heiress and philanthropist Rachel Lenox Kennedy (c. 1827–1898), took the artistic girl under her wing. Platt set up a studio in the Kennedy brownstone near Washington Square and, recently discovered photographs indicate, occasionally painted images of its Gothic revival library. Kennedy suffered from terminal cancer, and made plans to bequeath a substantial sum to Platt. But the will mysteriously vanished when Kennedy died. A nephew, Henry Van Rensselaer Kennedy, fought to inherit the entire estate—Platt and other witnesses testified that she had seen him skulking around the town house where the will was stored. Newspapers feasted on the trial transcripts.4 On the witness stand, lawyers portrayed Platt as an interloper, puttering amateurishly with “painting paraphernalia.” But they did not succeed in rattling her “reasonably acute” recollections, as she described her methodical but fruitless hunt for the will, which had been placed “in a green malachite box in a large vase in the corner of the library.”5

While the lawsuits dragged on, Platt rented quarters at the Van Dyck Studios, a then-new building at 939 Eighth Avenue (not far from other similar artist studio buildings named for Rodin, Rembrandt, and Gainsborough). She sublet easel space to other artists, and ran magazine ads for her drawing and painting lessons. At some point she took classes at the Art Students League, Columbia’s Teachers College, and Auguste Joseph Delécluse’s academy in Paris. She also studied with Henry B. Snell, a British immigrant specializing in painting watercolors by “the scrub method,” which he described as “boldly smashing in the masses of color on the dry paper with bristle brushes.”6 Platt lived and worked at the Van Dyck for the rest of her days.

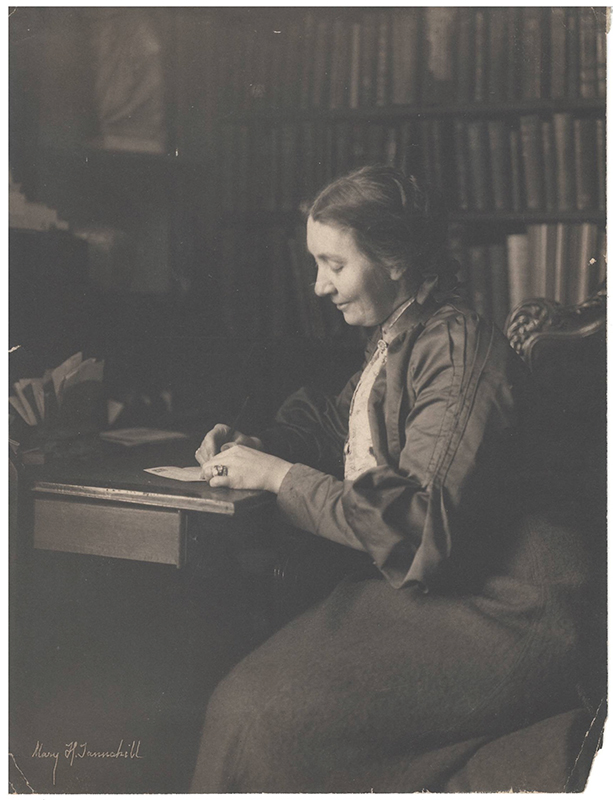

Studios there overflowed with “Oriental cosey corners, Chianti bottles in wicker, old brasses and coppers and artistic trifles from every corner of the globe.”7 Platt hosted open houses with neighbors, including the miniaturist Alta Wilmot, landscape artist Charlotte Coman, painter and textile artist Mary Tannahill, portraitist Marion Swinton, stained-glass designer Clara Weaver Parrish, and ceramists Edith Penman and Elizabeth Hardenbergh.

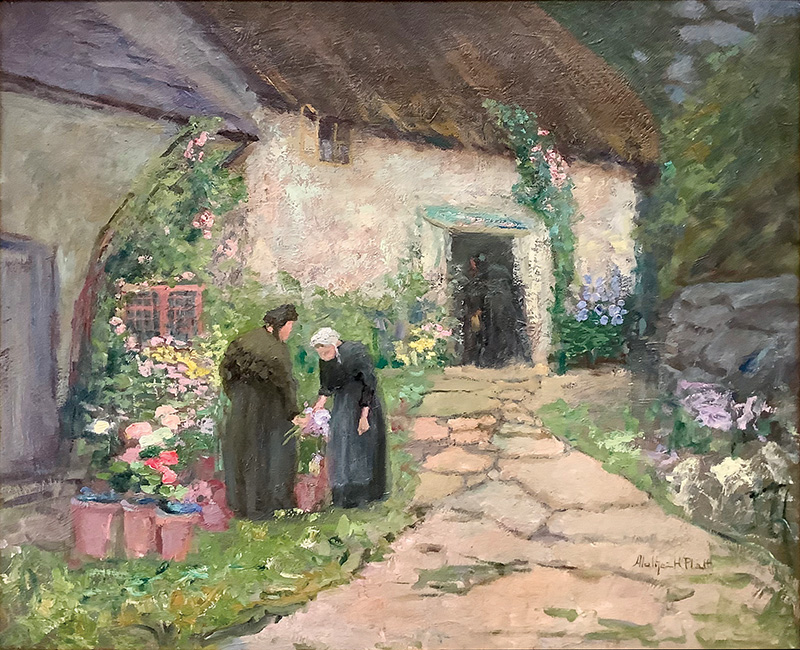

Platt’s summers were spent on the road, painting harbors, workshops, thatched farmhouses, and garden paths. Her destinations included Europe (particularly Devon, Cornwall, and Brittany), the Keene Valley in the Adirondacks, and Maine’s Boothbay Harbor. She also summered at her family’s shingled Queen Anne house in Sharon, Connecticut, named after a Native American wind god, Kabibonokka; she called her studio there Ellespie (perhaps based on her mother’s initials, L S P).

Another studio Platt used was in an eighteenth-century farmhouse in Woodstock, New York. She joked to her artist friend Ruth Payne Burgess that if her pragmatic brothers saw her ramshackle haunts, “they will seek a lunatic asylum.”8 She exhibited in hundreds of group shows, hosted from Boston to Sacramento, under the auspices of institutions including the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, the National Academy of Design, and the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors. She was a founder of the Society of Women Painters, set up in 1911 to export single-sex shows from New York, given the “strong prejudice against women’s paintings in this city.”9

In small towns that displayed Platt’s work, reformers were eager to expand museums and elevate public taste. When paintings by Platt, Swinton, Tannahill, Parrish and other Van Dyck neighbors arrived in Lawrence, Kansas, a local paper predicted it would amount to “the most popular exhibit that has ever been shown here.”10 Platt and her circle consigned works to Manhattan gallerists as prestigious as William Macbeth and the Knoedlers. Reviewers called her landscapes “brilliant in tone but true to the colors found in sky and plain and vale,”11 and praised her interiors for “quaintness of type and richness of color in shadowy corners and firelit hearths.”12

Her pace hardly slowed as she aged, although by 1930 her moorlands and cottages were considered “a little sentimental.”13 Among her travel companions was the landscape painter Fanny Griswold Ely, who tootled around Manhattan in an electric car.14 In 1930, a short Platt profile in The Spur magazine noted that she had emerged morally triumphant from the Kennedy estate battle and “now soared in realms far above worldly consideration.”15 By then Platt had written her own detailed will, “considering the uncertainty of this life.”16 She died suddenly in a Manhattan hospital after an operation. Canvases and watercolors in her estate included views of Boothbay Harbor, Brittany marketplaces, and Devonshire pastures.

Her relatives have hung onto Platt’s artifacts and paintings, including family portraits and a teenage sampler. Her artworks have circulated widely on the market, and a handful belong to institutions. A public library in Anderson, Indiana, owns a Platt cottage tableau that came to town in the 1910s (see Fig. 10). Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia, has Platt’s canvas depicting a woman stitching a textile while sitting alongside a woodburning stove, donated in the 1930s in a collection formed by Wesleyan grad Helena Eastman Ogden Campbell (see Fig. 12). The Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers University in New Jersey has shown Platt’s twilit shore scene in retrospectives for the National Association of Women Artists (Fig. 11).

Platt’s home in Sharon has subsequently belonged to the sculptor Beverly Pepper and her daughter, the poet Jorie Graham. Van Dyck Studios now contains mostly offices, and is dwarfed by the Hearst skyscraper next door. The studio building’s ornate facade stonework and a wooden staircase have scarcely changed since artists were in residence. The 2020 pandemic has blocked access to a number of archives containing Platt material. Perhaps more insights will emerge next year about this artistic descendant of Revolutionary War heroes, who blazed trails after being evicted from Greenwich Village.

1“Alethea Hill Platt’s Work,” New York Times, April 11, 1908, p. 6. 2“In and Out the Studios,” American Art News, vol. 10, no. 24 (March 23, 1912), p. 3. 3Lula Merrick, “In the Art World,” The Spur, vol. 46, no. 12 (December 15, 1930), pp. 70–71. 4“Rachel Kennedy’s Will,” New York Times, April 25, 1899, p. 14. 5Transcripts of voluminous court proceedings for Kennedy’s estate are available on Google Books. 6Henry B. Snell, “Scrub Water Color Painting,” Palette and Bench, vol. 1, no. 9 (June 1909), p. 197. 7“Reception by Artists,” New-York Tribune, December 11, 1903, p. 5. 8Platt’s undated letter to Burgess, John and Ruth Burgess collection, Jones Library, Amherst, Massachusetts. 9“Women Painters Organize,” New York Sun, January 3, 1912. 10“Many Artists Represented,” Lawrence (KS) Daily World, September 27, 1909, p. 3. 11“Pretty Art Shows in Many Galleries,” New York Herald, January 27, 1910, p. 11. 12“Alethea Hill Platt’s Work,” p. 6. 13Ada Rainey, “Fine Paintings On Exhibition At Arts Club,” Washington Post, April 27, 1930, p. S12. 14“Talk of the Town: Veteran,” New Yorker, vol. 14, no. 39 (November 12, 1938), p. 16. 15Merrick, “In the Art World,” pp. 70–71. 16Platt’s will, filed at the Westchester County Courthouse in White Plains, New York.

EVE M. KAHN, former antiques columnist for the New York Times, has written a biography of the artist Mary Rogers Williams (1857–1907) for Wesleyan University Press.

HANNA WELLS is a student at Brown University, majoring in urban studies.