The Magazine ANTIQUES | November 2008

Seymour Joseph Guy established a reputation in the United States in the mid-nineteenth century as one of the finest genre painters of children. His primarily cabinet-sized pictures were esteemed by his fellow artists and leading collectors of American art. He was widely respected for his technical ability and knowledge of the science of painting, but with the emergence of a younger generation of European-trained artists in the 1880s, Guy’s meticulous and smoothly polished scenes of childhood began to fall out of fashion. In recent decades his art and talent have been re-appraised by museums, scholars, and collectors of early American art, but up to now almost nothing has been published about his life and career.

Guy was born and raised in Greenwich, England, a parliamentary borough of London. He was the son of Jane Delver Wilson and Frederick Bennett Guy (d. 1833), and he had two brothers, Frederick Bennett Guy Jr. (1823–1899) and Charles Henry Guy (1824–1861). Following their mother’s death, probably in the late 1820s, the children were raised by their father, an innkeeper and owner of various commercial properties. Upon Frederick’s death in July 1833, the siblings appear to have been raised under the guardianship of John Locke, the proprietor of the Spanish Galleon, a tavern that still stands on Church Street in Greenwich, or John Hughes, a Church Street cheese merchant.1

Growing up, Guy attended a day school in Surrey.2 He developed an early interest in art, and was fond of painting dogs and horses. At the age of thirteen he expressed a serious desire to become either an artist or a civil engineer. His guardian responded by taking away his pocket money in hopes of motivating him to make a different career choice. Undaunted, Guy took up sign painting and earned enough money to buy the supplies he needed to continue his art education. For a brief period in the later 1830s he studied with a marine painter named Butterworth or Buttersworth—probably Thomas Buttersworth (1768–1842), who was a resident of Greenwich and had a successful career as a painter of ships and coastal scenes.

About 1839 Guy’s guardian convinced him to seek training as an engraver, but the expense of placing him as an apprentice with an engraving firm proved prohibitive. Instead Guy began a seven year apprenticeship in the oil and color trade, which entailed making pigments and preparing binders, as well as combining those ingredients to make paint either by hand-grinding or working a steam driven machine.3 The experience led Guy to grind and mix pigments for his own work.

Frederick Bennett Guy had stipulated in his will that his estate be divided among his children when Charles reached the age of twenty-one. This occurred about 1845, and closely coincided with the conclusion of Seymour’s apprenticeship and the death of his guardian, providing him with the freedom and means to pursue an artistic career. An influential friend by the name of Müller asked him if he wanted to study at the Royal Academy in London, but Guy preferred to study on his own at the British Museum. The next day Müller provided him with the necessary permit to set up his easel and copy paintings in the galleries, an opportunity Guy would later recall with great gratitude.4Guy decided to supplement his experience at the museum by joining the studio of the painter Ambrosini Jerôme (1810–1883). For a period of probably four years, he spent four days a week on his own and three days with Jerôme, who worked as a portrait, mythological, historical, and genre painter, and in the mid-1840s served as portrait painter to Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld (1786–1861), the Duchess of Kent and mother of Queen Victoria (r. 1837–1901). Under Jerôme’s tutelage, Guy focused on whatever brought in money—portraiture, designs for naval basins, “effects” for architects, and plans for ships in isometrical perspective. Guy had probably accrued knowledge of naval vessels while studying under Buttersworth, who had served in the Royal Navy.

In 1851 Guy exhibited Cupid in Search of Psyche (whereabouts unknown) at the British Institution. A small related version or sketch for the picture shows Cupid sitting on a shell that is propelled by a sail (Fig. 2). The picture foreshadows Guy’s later interest in depicting children, as well as his occasional enthusiasm for mythological and nude subjects. According to the National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, before leaving England Guy painted “many copies of old masters and painted portraits with much success in London.”5 In 1852 he married Anna Maria Barber (c. 1832–1907), daughter of William Barber, an engraver. The couple had nine children6 who undoubtedly served as models for their father.

In 1854 Guy and his family immigrated to New York, settling in Brooklyn. He briefly became a prominent figure in the art life of the city. For several years he had a studio in the Dodworth Building on Montague Street in Brooklyn Heights, which housed the studios of a number of the city’s leading artists. In 1857 he became a founding member of the Sketch Club there, and at that time may have first come into contact with the English-born genre painter John George Brown (1831–1913), with whom he would form a close friendship.7 For many years the two were virtually inseparable. Guy and Brown were probably initially drawn together by their English background and training and their shared penchant for minute workmanship and careful finish. During their years together in Brooklyn, Guy and Brown gravitated toward artists and collectors of British heritage. They formed close friendships with the Scottish-born collector and amateur artist John M. Falconer (1820–1903) and the English-born collector and restaurateur John Campion Force (1810–1875). During this period Guy painted several portraits, including one in 1859 of Benjamin G. Edmonds (1821–1895) (New-York Historical Society, New York), Captain of the Thirteenth Regiment of the New York State Militia headquartered in Brooklyn, which he considered to be among his finest.8

In 1861 Guy and Brown headed across the East River to the artistic shores of Manhattan. Guy took a studio at the other Dodworth Building on Broadway, and Brown moved into the Tenth Street Studio Building. In 1863 Guy followed Brown into the now legendary three-story brick structure, which opened in 1857 and over the course of the next decade became the bastion of the American artistic establishment.

Among the many prominent artists to reside there during the course of Guy’s forty-seven year occupancy were Sanford Robinson Gifford, Albert Bierstadt, Frederic Edwin Church, and William Merritt Chase.9

Guy began to paint genre scenes of children about 1861, taking his cue from Brown, who started to picture children in rustic country settings by 1859. It is likely that the two artists made frequent visits together to Fort Lee, New Jersey, in the early 1860s, and that it was while there that Guy’s art moved in this new direction. Fort Lee, which was quickly and easily reachable by ferry, remained an agrarian outpost of New York City until the 1920s. Brown settled in the town in 1864, and Guy and his family moved there from Brooklyn two years later.10 In 1873 Guy and his family returned to New York, where he remained for the rest of his life, inhabiting a series of different residences in the vicinity of East 120th Street in Manhattan.

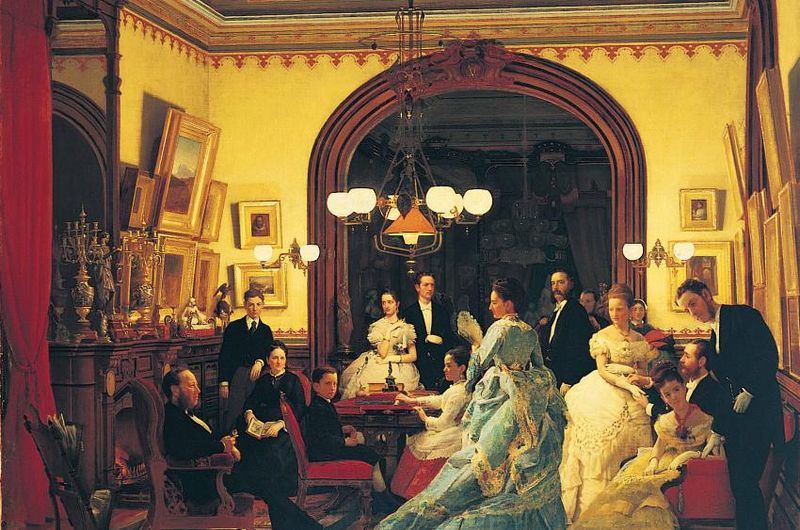

The majority of Guy’s genre scenes from 1861 to 1866 feature children playing in a country setting in summertime. A typical example is Open Your Mouth and Shut Your Eyes (Fig. 1), which is probably the work exhibited under the title Close Your Eyes at the Artists’ Fund Society in New York in late 1863. Several of Guy’s pictures of the period center on the interaction of a brother and sister, in which the sister is portrayed in the act of garnering her brother’s attention. As is typical of his genre paintings, the surface of the picture is marked by a smooth, glossy, enamel-like surface. Colors are carefully blended and fused, and brushstrokes are invisible. Guy’s early genre scenes typically include a picket fence, which spans the width of the background and creates a physical enclosure, which helps to convey a sense of intimacy, safety, and distance from the regular cares of the world. Also, small objects or pieces of furniture frequently appear in the right foreground of his scenes, such as the steps seen in Figure 1, which help to lead the viewer into the composition.About 1866 Guy developed a greater interest in creating interior genre scenes. His first major attempt to combine portraiture and genre painting was his 1866 work The Contest for the Bouquet: The Family of Robert Gordon in Their New York Dining-Room (Fig. 3). The Scottish-born Gordon (1829–1918) was a founding member and trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and had previously acquired Guy’s genre scene Love Launched a Ferry Boat (c. 1863, whereabouts unknown). The Contest for the Bouquet features the dining room of the Gordons’ house on West Thirty-third Street. Their extensive art collection, consisting mainly of American landscapes, is tiered on the walls of the elegantly appointed room. The vivid blue draperies and dress of the older daughter and the bright red leggings of the younger son add brilliant touches of color to the otherwise subdued tones.11

The setting for the picture provided Guy with a rare opportunity to completely articulate a large interior space, and he masterfully handled the rendering of the room’s perspective. During his lifetime he was highly regarded for his knowledge of perspective, and was sometimes called upon by colleagues seeking help with their compositions. In 1885 a writer for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle remarked that Guy was “deeply versed not only in the mechanism of painting, but in perspective, and has made some valuable observations in the measurement of distant objects and the effect of distance on color and light.”12 It was also reported that Guy “can analyze a composition, scale its merits and defects and reveal its hidden curves and lines as accurately as the chemist analyzes a drug.”13

The primary focus of The Contest for the Bouquet is on the three children standing in the left foreground, two of whom playfully attempt to grab the bouquet from the outstretched hand of their older brother, whose other hand firmly holds onto his school books. Guy’s genre paintings regularly feature books that are either held in a child’s hand or that have been momentarily put aside because of an interruption or distraction. A number of pictures also center on mothers reading to their children. The three children are probably angling to see which one of them will have the honor of presenting the floral bouquet to their mother, who looks on calmly from her chair while holding her youngest daughter. Interestingly, the arrangement of figures brings to mind Jacques Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii of 1784 (Musée du Louvre, Paris). In addition to combining portraiture and genre, Guy appears to be slyly alluding to French neoclassical history painting, an unexpected source for such a playful family scene.

In October 1867 Guy followed up The Contest for the Bouquet with his painting Evening (Fig. 4), which was commissioned by John M. Falconer and features a portrait of his mother, Catherine Stewart Falconer, seated in the picture-lined parlor of John’s Brooklyn house.14 A gas lamp bathes the corner of the room in a warm radiant glow and casts a double reflection on the glass covering the picture at the top center. The reflections help create the impression of greater spatial depth. The painting is a tour de force of reflections and shadows. Mrs. Falconer’s head casts a large shadow on the picture immediately to her left and creates a reflection on the glass covering the print hanging behind her. The work is composed of a complex layering of opaque colors, glazes, and scumbles, and the overall color scheme is dominated by lush reds and browns. Above all, Guy was concerned with the careful and meticulous rendering of tonal values. This remained true throughout his career, even on those rare occasions when he employed a brighter and more varied palette.

Evening is one of a series of pictures that Guy painted between 1867 and 1873 that feature an interior bathed in the light of an oil lamp, gaslight, or candle. Contemporary critics and art writers felt that he rendered such effects with striking success and reported that he “studied the problems of artificial light scientifically.”15 Natural and artificial light appear side by side in Making a Train (Fig. 6), which depicts a partially disrobed young girlplaying dress-up in an attic bedroom flooded by moonlightfrom a dormer window. The child’s pose is partially echoed in the print that hangs precariously from a single nail on the wall behind her, a mezzotint engraving after a well-known painting of about 1776 by Sir Joshua Reynolds (1723–1792) entitled The Infant Samuel (Tate Britain, London). That work features an image of the devout little boy Samuel kneeling in prayer in a ray of moonlight that streams into his bedroom from the open window beside him. Evidently, Guy meant the viewer to draw a connection between the vanity of the young girl and the piousness of young Samuel. In the United States in the mid-nineteenth century, it was common for artists to explore the nude within the coupled context of innocence and Christianity. Here it seems that the young girl, who has put her book and oil lamp down on the chair in order to amuse herself in the light of the moon, is in danger of veering from the path of virtue and innocence.16Children in Candlelight (Fig. 5)dates from 1869 and is probably the painting originally titled Who’s There?17 In his paintings of candlelight scenes, Guy followed in the European tradition of Gerrit van Honthorst (1590–1656), Georges de La Tour (1593–1652), and Joseph Wright of Derby (1734–1797). In this canvas, as in works by those artists, the sole source of illumination is a candle, dramatic effects of light and shadow are emphasized, and there is a powerful and almost eerie sense of mood. The art historian William H. Gerdts has remarked that Guy’s picture is “fascinating, not only as a social document but also for the exquisite technique and most of all, for the treatment of light….The candle is shielded by the little girl holding it, making her hand translucent and creating brilliant, dramatic transitions from intense light to deep dark.”18

In 1873 Guy received the most important and controversial commission of his career, a portrait of William Henry Vanderbilt and his family posed in the drawing room of their home at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Fortieth Street in New York (Fig. 7). Vanderbilt had become fond of Guy during the course of his frequent visits to the Tenth Street Studio Building, where he acquired genre paintings by Guy, Brown, and other artist tenants.19 Apparently he presented Guy with the grouping, idea, and motif for the work, which features him and his wife surrounded by their children, who are about to step out for a night at the opera.20 Vanderbilt may have conceived this combination of portraiture and genre after seeing Guy’s painting of the Gordon family. In the early 1870s Vanderbilt was not well known to the public, having yet to emerge from the large shadow of his father “Commodore” Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794–1877), then considered the wealthiest man in the country.

Going to the Opera was displayed at the 1874 annual exhibition of the National Academy of Design, where it attracted great crowds because of its representation of members of such a prominent family, but received a generally poor reception from the art critics. Guy escaped blame for what the critics saw as deficiencies in the painting’s setting and subject, which they felt he had been obligated by his patron to represent. Several mentioned that the room was simply too small to gracefully contain such a large group of figures. The critic for the Nation also thought that the room was poorly decorated, and criticized “the complete want of individuality in the furniture, the expressionlessness of every inch of background, the machine made look of the carvings, the iron oppressiveness of the black arched molding, completely at war with the wall decoration, etc.”21 Another writer criticized the room’s color, noting that the “dull buff brown of the walls, lit up by the yellow light of the gas, too nearly coincides with the gilding on the frames, and not even the mat of black which encircles the picture can break the continuity.”22 The critic for the New York Evening Express felt impelled to mention Guy’s picture in the context of commenting that family groups “on canvas are abominations at the best, but when the figures are dressed up in spic-and-span new clothes, and introduced much after the manner of a fashion-plate they become doubly offensive.”23

In 1876 the artist and journalist Thomas Bangs Thorpe (1815–1878) published an article about Guy and his work in Baldwin’s Monthly. It includes a strong defense of Going to the Opera and was likely fueled by Guy’s own feelings about the attacks and the merits of his canvas, for the two were friends. Thorpe wrote that the critics had generally missed the work’s higher aim as a work of art, and that this had resulted in a great loss of opportunity for American art. Thorpe believed that had

the exalted notion of domestic affection that prompted the creation of this picture been properly, considerably treated by the “art critics,” there is no doubt but that the fashion of having portraiture combined with the charms of genre pictures, would have been established…. It would fill our parlors with exquisite works of art, and preserve the exact likeness of face and dress of our handsome, unsurpassed women, as they appear in the era of representation, giving these pictures in time, not only the highest value as works of art, but also a most pleasing historical importance.24

Following the exhibition of Going to the Opera, Guy devoted most of his attention for the next decade to creating generally small domestic genre scenes, such as Up for Repairs (Fig. 9) and Temptation (Fig. 8). He never again created a work on the scale and ambition of the Vanderbilt picture. During the 1880s he returned to creating portraits on a regular basis and also developed an interest in painting ideal heads, sometimes portraying a woman in a picturesque setting or out being entertained (see Fig. 10). In his later works he continued to paint slowly and deliberately, to employ a careful glazing technique, and to prefer a smooth lacquered surface. From about 1874 onward there was growing criticism of Guy’s paintings for their polished technique and lack in variety of texture. The important writer and historian of American art Samuel G. W. Benjamin (1837–1914), for example, felt that his works were overly elaborate in technique and that this robbed them of “freshness and piquancy.”25 Guy also had his defenders, such as the art writer and curator Sylvester R. Koehler (1837–1900), who in 1886 noted that “Guy values elegance and finish more than the facility which is the charm of much of the work now current, he has frequently, and most unjustly, been assailed of late,—even while the same qualities in [contemporary] French painters were reckoned of value, and his deeper qualities have been overlooked.”26

By the time of his death in 1910, Guy was almost completely forgotten as an artist. During the last decade of his life he seems to have served as something of an elder statesman to younger artists interested in increasing their knowledge about the art and craft of painting. The lengthiest eulogy for Guy appeared in the Century Association’s annual publication dealing with club affairs, where it was related that Guy

is remembered with deep affection by artists who came to him as to an older man of recognized position. He was most genial, cordial, and ready to place himself and the methods of his art at their disposal, rejoicing in their companionship and keeping himself young through participation in their pursuits. For twenty-two years he was of the rare artistic fellowship of The Century, though of late years, through the infirmities of age, seldom here.27

Today it is time to linger again before Guy’s canvases and appreciate their special beauty, charm, and technical virtuosity.

1 I would like to thank Rita Ford, the great-granddaughter of Seymour Joseph Guy’s brother Frederick, for the information and references she provided concerning Guy’s English family background, and for informing me about the 1833 will of his father Frederick Bennett Guy. Locke and Hughes served as executors and administrators of the will, and it is probable that one of the men became the guardian of the three Guy children. The will is in the National Archives in London. 2 For Guy’s early life and training in England, see George W. Sheldon, American Painters (New York, 1881), pp. 65–66; and the entry for the artist in National Cyclopaedia of American Biography (James T. White and Company, New York, 1901), vol. 11, p. 301. 3 In an email of June 10, 2007, the painting conservator Leslie Carlyle, who is an authority on British nineteenth-century painting manuals and treatises, kindly supplied information about the responsibilities of an English apprentice in the oil and color trade. 4 Sheldon, American Painters, p. 66. 5 National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, vol. 11, p. 301. 6 Sheldon, American Painters, p. 67. 7 I would like to thank Martha J. Hoppin, the John George Brown authority, for informing me about Guy’s close friendship with Brown and their time together in Fort Lee, New Jersey.8 Guy expressed his regard for this portrait in a letter he wrote to John M. Falconer. See Kindred Spirits: The E. Maurice Bloch Collection of Manuscripts, Letters and Sketchbooks (Arts Libri, Boston, 1992), p. 36. 9 On the Tenth Street Studio Building, see Annette Blau-grund, The Tenth Street Studio Building: Artist-entrepreneurs from the Hudson River School to the American Impressionists (Parrish Art Museum, Southampton, N.Y., 1997). For an account of Guy’s reception in the building, see “On the Easel,” New York Evening Mail, April 8, 1869, p. 6. 10 For references to Guy’s activity in Fort Lee, see “Art Notes,” Round Table, n.s. 1, no. 1 (September 9, 1865), p. 7; and “Art-Feuilleton,” Art Journal, vol. 1 (November 15, 1867), p. 14. The United States Census of 1870 lists Guy and his family as living in nearby Hackensack. 11 See “Fine Arts. The Artists’ Fund Exhibition,” Albion, vol. 44 (November 24, 1866), p. 561, which discusses Guy’s difficult task of introducing portraiture into a scene of daily life. 12 “Gallery and Studio,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 9, 1885, p. 2. 13 “Gallery and Studio. Scientific Measurements as a Help to Picture Making. Mr. Guy’s Discovery,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 13, 1885, p. 2. 14 Evening was included in the 1868 annual exhibition at the National Academy of Design, and critics were quick to praise Guy’s harmonious intermingling of genre and portraiture. See, for example, “Fine Arts. National Academy of Design,” New York Daily Tribune, June 18, 1868, p. 2. 15 National Cyclopaedia of American Biography, vol. 11, p. 301. 16 Making a Train is discussed at length in David M. Lubin, Picturing a Nation: Art and Social Change in Nineteenth-Century America (Yale University Press, New Haven, 1994), pp. 205–271. 17 Who’s There? was among a group of works donated by the Artists’ Mutual Aid Society for an auction to benefit the widow of the artist Emanuel Leutze (1816–1868). A notice of the auction reported of Guy’s painting: “The effect of the light upon her face is fine.” “Art Items,” Philadelphia Daily Evening Bulletin, Feb. 16, 1869, p. 2. 18 William H. Gerdts, “Additions to the Museum’s Collections of American Paintings and Sculpture,” [Newark] Museum, n.s., vol. 13 (Winter-Spring 1961), p. 20. I would like to thank Abigail and William H. Gerdts for permitting use of their library on American art during the course of researching this article. Sharon Newfeld, Nadja Hansen, and Maeve Connell also provided assistance. 19 W. A. Croffut, The Vanderbilts and the Story of Their Fortune (Chicago, 1886), p. 164. For a recent discussion of the painting, see Darlene Marshall, “The Character of Home: The Domestic Interior in American Painting, 1862–1893” (PhD diss., Pennsylvania State University, 2005), pp. 175–199. 20 See Thomas Bangs Thorpe, “Painters of the Century—No. VIII. Our Successful Artist—S. J. Guy,” Baldwin’s Monthly, vol. 13 (August 1876), p. 1, which strongly infers that Vanderbilt originated the idea for the painting. 21 “Fine Arts. The National Academy Exhibition,” Nation, vol. 462 (May 7, 1874), p. 304. 22 “Fine Arts: The Exhibition at the National Academy,” New York Evening Mail, April 17, 1874, p. 1. 23 “Our Feuilleton. The Academy Exhibition,” New York Evening Express, April 3, 1880, p. 1. 24 Thorpe, “Painters of the Century,” p. 1. 25 Samuel G. W. Benjamin, Art in America (New York, 1880), p. 115. 26 Sylvester R. Koehler, American Etchings (Boston, 1886), p. 54. 27 Reports, Constitution, By-Laws and List of Members of the Century Association for the Year 1910 (Knickerbocker Press, New York, 1910), p. 42. I would like to thank Jonathan P. Harding, curator of the Century Association, for bringing this reference to my attention.

BRUCE WEBER is the senior curator of nineteenth-century art at the National Academy Museum in New York.