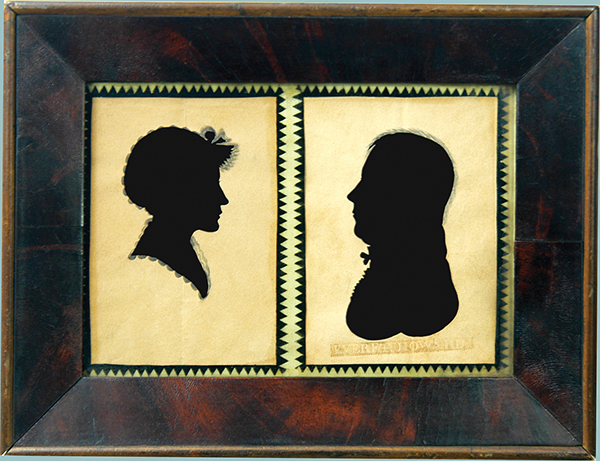

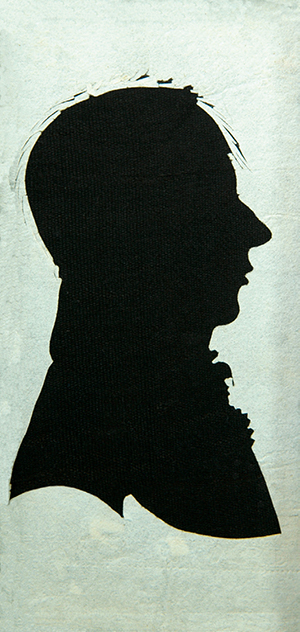

Fig. 2. Silhouette portraits of a man and a woman by Howard. The man’s portrait is signed with the artist’s embossed stamp (type 1) at bottom. Paper and black cloth, each 3 ⅝ by 2 ¾ inches. The man has an unusual double scalloped bust-line termination. The woman’s likeness displays several characteristics seen on signed examples of Howard’s work, including details added to her mobcap and half-circles drawn around the figure. Courtesy of Peggy McClard Antiques.

In December 1820 newspapers in Boston and Hallowell, Maine, reprinted an apathetic obituary that had first appeared in a Georgia newspaper: “In Jackson County, (Geo.) Everett Howard. He is believed to have been a limner [portrait painter] by occupation, but as he came sick of a fever, of which he died, little is known of him or his connections.”1 The Hallowell newspapers added, “From the above account, we presume the deceased was Mr. Everett Howard, late of Leeds in this County.” No one bothered to erect a gravestone marking the life and burial of Everet Howard. In spite of this lack of interest in him and his art when he died, Howard was one of the few early nineteenth-century American silhouette and small watercolor artists who left written accounts and family documentation that describe his motivations and difficulties.2

Everet Howard was born in West Bridgewater, Massachusetts, to Seth and Desire Howard, descendants of the first English colonists at Plymouth Colony.3 During 1801 the family, which included seven children, moved to unimproved frontier land in the middle of the District of Maine, then part of Massachusetts. In the recently established town of Leeds on the Androscoggin River, Howard’s father prospered as a trader and farmer. As the family grew to nine children, they would occupy one of the town’s most prominent homes overlooking the river. To further his education beyond what was available at the local school, Howard was sent back to Massachusetts to attend the Bridgewater Academy. By age seventeen, he was teaching school in Jay and Topsham, Maine, not far from Leeds.

Starting on his twentieth birthday, Howard kept a daily diary between November 1807 and August 1808 in which he detailed the events of his life and process of becoming an artist. First entry records that, while continuing his education at “Dr. Currier’s,” Howard also played the flute, went to singing school, and made portraits. “I draughted Mr. Smith’s likeness,” he wrote. It was common at this time for advanced students to teach in a local school, particularly during the winter months. Employed to teach in Readfield, Maine, when the new term began on January 11, 1808, Howard unexpectedly found that the size of the class had grown to a hundred students. “[I] ferruled a number of the scholars but whipping did not much good.” With the students simply “ungovernable,” he quit: “Dismissed my school this day about 4 forever—I felt exceedingly well pleased.”

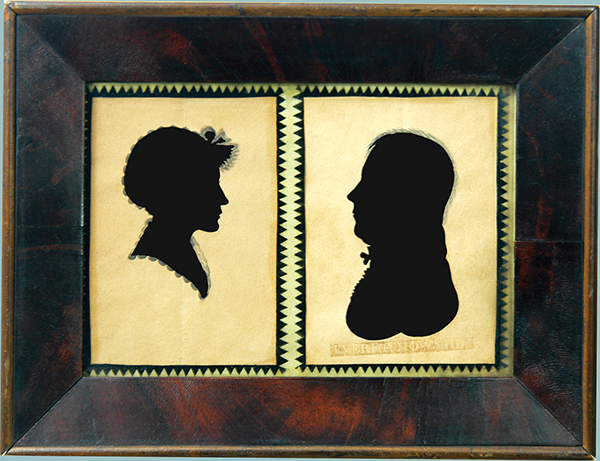

Fig. 3. Imprint from Howard’s signature embossing stamp (type 1).

After abandoning the idea of a teaching career, Howard’s opportunities were limited. Prior to the War of 1812, the federal government passed the Non-Importation Act (1806) and the Embargo Act (1807), which decimated the mercantile base of Maine, resulting in major bank failures along with the personal bankruptcy of many leading citizens. Additionally, farming was mired in land-claim disputes from earlier English royal land grants.4 Howard returned home to Leeds and directed his efforts toward the art he had enjoyed in his spare time.

Before photography was introduced to America in 1839, itinerant artists who stopped in every little town could provide sitters with an oil portrait, a small watercolor portrait on paper or ivory, or a silhouette (also called at that time a shade or profile). Silhouettes were particularly popular due to their low cost and the “science” of physiognomy that had developed in the late eighteenth century. While the correctness of its theories was much debated, physiognomy purported that a person’s living character could be read from the facial outline in a silhouette.

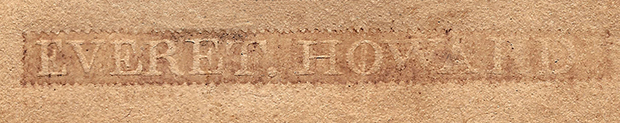

Fig. 4. Silhouette portrait of a young woman by Howard. Signed with the artist’s embossed stamp (type 1) at bottom. Paper and black cloth, 3 by 2 ¾ inches. This silhouette shows a livelier pattern than usual, with details such as slashed cuts around her hair, a cutout falling lock of hair, and the exaggerated ruffles of the dress. Courtesy of Peggy McClard Antiques.

Physiognomy required the most accurate possible silhouette to correctly interpret the sitter’s personality.5 Howard wrote in his diary on May 25, 1808, “I began on a new invention—a Profile Machine—I had heard of Thompson’s machine to take profiles by the shade and I concluded there must be an easier way—therefore I formed a wooden thing from my own invention—it took me some time to form and invent it to my liking—but I finally got it so that by moving a rod round a person’s face I could cut the profile exactly like them in a smaller compass.” Still not happy with his results, however, Howard “heard that one Moor from Farmington [Maine] was at Levett’s with a profile machine.” He traded his horse, saddle, and some picture frames for Moor’s machine.

On Wednesday, June 8, 1808, “after receiving advice from my parents I started on a long journey—I rode to Wayne [ten miles from Leeds]—set my machine up and took three profiles.” is was the beginning of a twelve-year itinerancy that took Howard thousands of miles, from Maine to Georgia to Canada, and myriad other locales. Journeying to Hallowell and then to Topsham with “severe trials in my mind with regard to setting up with so much expense on business of an unknown aspect,” he “was much encouraged” by the end of the week, recording, “I cleared 7 dollars in 5 days past.” Traveling through Maine coastal towns to Wiscasset, he lost “almost a dollar in gambling,” attended a puppet show, danced until one in the morning, and spent an evening playing cards, although he “had almost sworn against it.” He also went “to see some of Brewster’s portrait likenesses,” referring to John Brewster Jr., the celebrated deaf-mute portrait painter from Buxton, Maine. In Bath, Maine, Howard established a pattern he repeated when visiting a new location. He would hire a room in a tavern, “spread handbills about town” (Fig. 6), and meet as many people as possible. He was delighted to find that artists’ supplies were readily available in Bath, including frames, paper, and an artist who could produce black reverse-painted glass for the frames of his silhouettes and small portraits.

Instead of going by horse to Brunswick, Maine, in July 1808, Howard “rode in a chaise” for the first time. On July 26, he noted his success with the students and faculty at Bowdoin College in Brunswick: “did very well this day for wages—took as much as Congressman—Six Dollars—took the profiles of men, women, and children.” For two dollars he had an embossing stamp made to sign his profiles and small portraits (Fig. 3).6 With financial help from his father, Howard then purchased his own chaise, which allowed him to travel more comfortably and carry more personal and professional supplies. Soon thereafter, in August 1808, he ceased making entries in the diary.

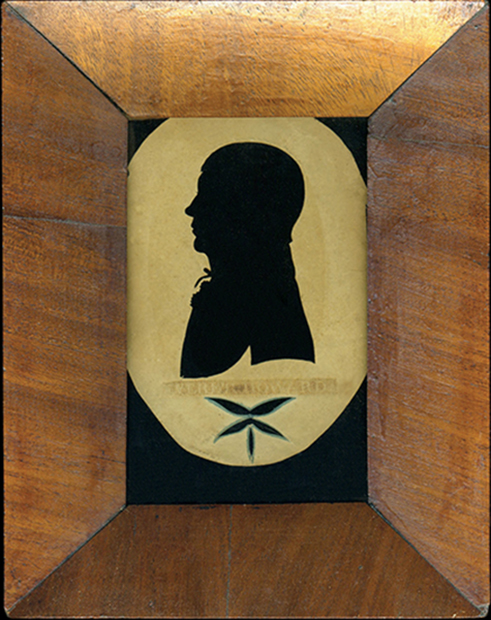

Fig. 5. Portrait silhouette of a man by How- ard. Signed with the artist’s embossed stamp (type 1) at bottom. Paper and black cloth,

3¾ by 2 1⁄2 inches. Howard embellished the silhouette with the knot of the cravat, frilled shirt, and the unusual design below his embossed signature. Courtesy of Willis Henry Auctions, Marshfield, Massachusetts.

Additional documentation about him was found in the Howard family papers preserved at Bowdoin.7 The papers contain numerous letters between Howard’s brothers, who mostly settled in the lower Hudson River valley of New York, and their parents that often described Howard’s activities and travels.

Fig. 6. Handbill of Everet Howard, published in Lester Parker, “Diary of a Young Man, 1807–08,” The New-England Galaxy, vol. 7, no. 1 (Summer 1965), p. 2. Image courtesy of Old Sturbridge Village, Sturbridge, Massachusetts.

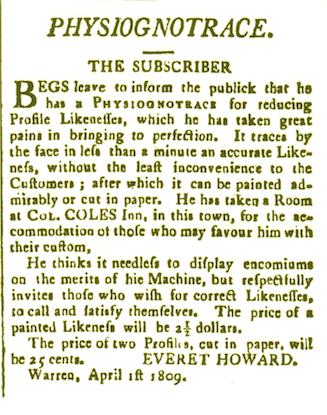

By April 1809, he was traveling long distances. In Warren, Rhode Island, his advertisements promoted the advantages of his physiognotrace machine and offered two silhouettes for twenty-five cents or small watercolor portraits for $2.50 each (Fig. 7). Howard’s silhouettes captured the sitter’s facial features with great sensitivity and he always added delicate details to the image, such as a tiny cutout eyelash (Figs. 1, 2, 4, 5, and 10). Women’s portraits always include cut additions, such as ribbons on their mobcaps or around their necks, or pencil embellishments around the silhouette. Men’s portraits include personalized details such as the sitter’s hair, necktie, or frilled shirt. Howard is known for using slashing cuts to portray hair (Figs. 4, 10). Although there are variations, most of his silhouettes have a distinctive bust-line termination that includes the sitter’s shoulder and top of the arm.8

Howard’s small watercolor portraits show that he quickly became an accomplished watercolorist. In a portrait from 1810, the woman is depicted with unusual white-gray skin coloring and facial details in subdued blues and grays (Fig. 8). These cool, receding color values deemphasize her face, and the viewer’s eye is unexpectedly drawn to the yellow of her earring and hair combs. At the beginning of the nineteenth century, the young woman’s black dress would have implied that she was in mourning. The lack of strong coloration, the mass of black in her hair and dress, and the blue at the edges of the image produce a somber, muted portrait that imparts a sense of quietude and dignity. Similarly, in the carefully delineated image of Charles Ring in Figure 9, the facial details colored using gray tones convey a feeling of solidity and sensitivity.

Fig. 7. Howard’s advertisement in the Bristol County Register, Warren, Rhode Island, May 1, 8, and 15, 1809.

Life as an itinerant artist was a difficult one. Howard never married and had no home of his own. On two separate occasions, his health so deteriorated that the family gathered in anticipation of his death. In the first instance, a letter dated July 9, 1810, records that his parents were traveling from Leeds to be with him in Frederick, New York. They “are in good spirits after hearing that Everet was yet alive and a little better,” and that Dr. Rowland Bailey, Howard’s uncle, had traveled from Poughkeepsie to examine him.9 Though the letter continued that Bailey had found that “it should be best for him to have his leg taken off,” Howard’s future itinerancy, traveling many thousands of miles, indicates that the leg was saved.

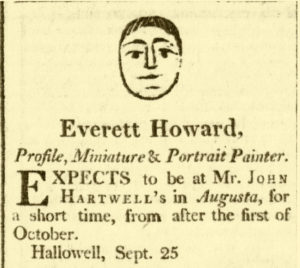

When Howard traveled to a new town, he often advertised his arrival, location, and anticipated departure date in the local newspaper. For his ad in the Hallowell American Advocate in October 1811, he incurred the extra expense of including a face, creating what we consider one of the most charming advertisements by an American folk portrait painter (Fig. 11).

During 1812 Howard was in Yorktown, New York, at the home of his brother Ward. In early 1813 he was off “to Poughkeepsie where he tarried a few days and painted fine pictures…in perfect health.” He also painted in New York City, and the city directory listed him as an artist that same year. He then moved on again, traveling north and arriving at Sackets Harbor, New York, on the shore of Lake Ontario at the beginning of 1814.

Fig. 8. Portrait of a woman in mourning by Howard. Signed with the artist’s embossed stamp (type 2) at lower right. Watercolor on paper, 4 1⁄2 by 3 1⁄2 inches. When the frame of this portrait was opened in 2016, the original receipt in Howard’s hand- writing was found inside: “MAY THE 3RD 1810/ FROM PULBY RECEIVED/ & PAYMENT TO HIM/ HOLDEN/ LEEDS/ FOUR DOLLARS WITH INTER- EST $4.” This may represent Howard’s advertised fee of $2.50 for a watercolor portrait and the cost of the frame. Holden could be the town in either Maine or Massachusetts. Collection of Michael and Suzanne Payne.

Fig. 9. Charles Ring by How- ard. Signed with the artist’s embossed stamp (type 2) at lower right. Watercolor on paper, 4 1⁄2 by 3 1⁄2 inches. The sitter is identified by a note on the reverse. Collection of Don and Edythe Aukerman.

Prior to the beginning of the War of 1812, the United States War Department had understood that naval battles on the Great Lakes would be a major component of the impending conflict. To defend against a possible invasion from Canada, Sackets Harbor was transformed into a major defensible position with thousands of sailors and soldiers and a massive shipyard employing more than three thousand workers. As then the third largest city in New York State, it would have provided a large clientele for Howard’s portraits. The British had attacked the town in 1812 and 1813 but were repulsed both times. Howard wrote to his parents: “Being in perfect health and thinking nothing would hurt me having frequently wet my feet during the storms,” he returned to his boardinghouse and the room he shared with a Colonel Bebe, who was sick. The next day, Howard was also ill. “I continued there almost a week,” he wrote poignantly, “with no person to wait upon me… I thought it time to move myself if I wished to live.” With great diffculty, he managed to make the long trip back to his brother Rowland’s home in Poughkeepsie.

In late July 1814 Rowland wrote to their parents, “For near seven months Everet was with me and little did I think we should be separated until the curtain of life closed the sun forever—Physicians Friends & acquaintances and he himself for a long time gave up all hope of his recovery.” Yet, Howard had decided to travel back to Leeds. His brother wrote, “I had no expectation of his starting altho he had long had it in contemplation but his feeble health I expected would baffle his resolution.” Rowland concluded, “Please to remember me to Everet—may natures grate [sic] Physician soon restore him to perfect health.” Letters between relatives soon mentioned “the recovery of Everets health, & I assure you that I am much pleased to hear so favorable news.”

In January 1815 Howard was again back with Rowland, who wrote that “the pain in his breast has entirely ceased and he has grown very fleshy.” Howard then decided to travel north to “White Hall on Lake Champlain” and to Plattsburgh, New York, where he was “doing well…in tolerable health,” Rowland reported. By December 1815 Rowland wrote that Everet was now with him in Peekskill, New York, in perfect health and painting portraits of the brothers and “many other pictures in this place but talks of leaving this for new york city soon.” The following year Howard was listed in one of the New York directories as a “miniature painter” at 210 Broadway. His brother Seth wrote on July 20, 1816, that the two met up in the city and traveled together to Seth’s home in Poughkeepsie, where Howard advertised his portrait services.

Fig. 10. Silhouette portrait of a man by Howard. Signed with the artist’s embossed stamp (type 1) at bottom. Paper and black cloth, 3 ¾ by 1 ¾ inches. Courtesy of Peggy McClard Antiques.

Starting in 1817 Howard undertook a series of lengthy painting trips. Rowland wrote to their parents: “Everet I heard from the 20 of April [1817] then in Savannah in Georgia have made much money & was in the best of health.” Rowland wrote again on January 30, 1818, that “Everet went from Ohio to Pittsburgh hence to Erie on Lake Erie where he wrote last he was on a sleigh then going to Kingston [Ontario] Montreal & Quebec and then to Maine or Europe—the last improbable.” He was well “except for his old acquaintance the Ruematism.” Like many American artists during the first half of the nineteenth century, Howard presumably found the large number of possible customers in the major Canadian cities, along with the ease of water transportation, irresistible.

From May through October 1819, Howard was back in Peekskill and helping his brother Ward. His brother Seth complained to their parents: “Everet started from here day before yesterday [November 7, 1819] for the South, he has conducted [himself ] so imprudently, that I think he has not a friend in Peekskill except his brothers, from what I can understand Ward has conducted every [?] & liberally towards him paid him principal & interest for everything he ever had of him & charged him nothing for any expense he has been with him since he has been living here. I am sensible he never will be thanket for it—.”

Howard’s family in Leeds only learned of his death in Georgia when the local Hallowell newspapers printed the simple two-sentence obituary in December 1820. Two years later, in 1822, his brother Ward tracked down a man in Virginia who knew the particulars of Howard’s last journey. Ward wrote to their parents that Everet had died “sick of a fever” on November 23, 1820, aged thirty-three, in Jackson County, Georgia. He had probably been attracted to this rural county by the large numbers of possible customers at Franklin College, now the University of Georgia.

Letters between relatives expressed their sympathy. A cousin wrote to Rowland: “You have no doubt ere this received a letter…containing the afflicting intelligence of your brother Everet’s last illness and death…I think the death of your brother E. must be doubly afflicting to you and conclude that though I can do but little toward mitigating your sorrows my letter will not be unwelcome…but alas! all I have to offer is a sympathizing heart.”

Fig. 11. Howard’s advertisement in the American Advocate, Hallowell, Maine, September 25 and October 2, 1811.

When the history of Everet Howard’s family was recorded, the lives and many children of his brothers and sisters were chronicled at length, but the description of his life was short: “Everet went hither and thither, painting and leaving likenesses instead of children and grandchildren to perpetuate his memory, always roving until his death.”10

1 The obituary appeared in the Boston Commercial Gazette, Hallowell Gazette [Maine], and American Advocate and Kennebec Advertiser [Hal- lowell]. 2 Lester Ward Parker, “Diary of a Young Man, 1807– 08”, The New-England Galaxy, vol. 7, no. 1 (Summer 1965), pp. 31–42. This article was based on Everet Howard’s diary, which had descended in the family of the author’s wife, Katherine Howard Parker. Quotes and information about Howard through 1808 are from this source. Our attempts to find the original diary were not successful. After an extensive library, museum, and historical society search, we wrote letters to sixteen possible relatives of the late Lester and Katherine Parker. A granddaughter was located who maintains Lester Parker’s family genealogical research, but does not have the diary. Her attempt to find it by contact- ing other family members was unsuccessful. 3 The artist always spelled his first name Everet, but it was sometimes recorded as Evrit or Everett. 4 Alan Taylor, Liberty Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 1760 –1820. (University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill, 1990). 5 Ellen G. Miles, “1803—The Year of the Physiognotrace,” in Painting and Portrait Making in the American Northwest, ed. Peter Benes (Dublin Seminar for American Folklife in association with Boston University Press, Boston, 1994), pp. 118–137. Despite physiognomy’s supposed requirement for an exactly traced outline, artists improved on the aesthetics and individualized representation of their work by cutting beyond and within the tracing of the profile and adding details with cutwork or pencil. The stylistic additions developed by many artists often allow the attribution of an unsigned silhouette to a particular artist. 6 We have seen two styles of embossing stamp. Type 1 has a saw-toothed rectangular border with his name depicted in raised letters within a flat field. Type 2 has no border and the letters of his name are impressed into the paper. 7 Rowland Bailey Howard papers (M092) and Oliver Otis Howard papers (M091), George J. Mitchell Department of Special Collections and Archives, Bowdoin College Library, Brunswick, Maine. All information and quotes, after the end of Howard’s diary in 1808, are from letters in these papers associated with Howard’s brother Rowland’s three sons who attended Bowdoin College. One became a prominent minister and two became Union generals during the Civil War. General Oliver Otis Howard was an important historical figure, particularly in the federal government’s efforts during Reconstruction. Howard University in Washington, DC, is named for him and he served as its president. 8 Silhouettes with elaborate cutout curlicues at the bust-line have been attributed to Howard, such as the examples from the collection of Emerson Greenaway sold at Richard Withington Inc., Hillsborough, New Hampshire, on August 31, 1990, and March 2, 1991. We have been unable to locate a signed silhouette with this unusual feature to support this attribution. 9 The town of Frederick, New York, was renamed Kent in 1817. The authors (Paynes) note that this is the neighboring town to their home, which was built in the late 1790s on the local turnpike. As this was the major road between these towns and to the larger nearby cities. Howard would have constantly traveled in front of their house. 10 Typed notes for the address written and delivered by General Oliver Otis Howard at the centennial celebration in Leeds, Maine, on August 15, 1901, in the Oliver Otis Howard papers at Bowdoin.