Geography is a subject not widely studied in our schools today. Most Americans would have a hard time identifying even a handful of foreign countries on a map, let alone be able to draw their outlines. For the students of a Quaker boarding school in southeastern Pennsylvania two hundred years ago, however, such information was a regular part of the academic curriculum. For some, the school’s geographical instruction served as the foundation for an array of silken globes that still catch our eye with their beauty and charm, and with the remarkable range of knowledge and skill they represent.

Established by members of the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends in 1799, Westtown School is a co-educational boarding school that still flourishes on the six hundred–acre campus in rural Chester County, Pennsylvania, that was purchased for its use in 1794. In the early nineteenth century, the school offered classes in reading, writing, arithmetic, English grammar, religious studies, and geography. In addition, girls were instructed in the arts of sewing, knitting, darning, and embroidery. Westtown also established the unusual practice of creating silk globes.

The school has in its archives a large collection of historic samplers from between 1800 and 1843, the years in which Westtown’s “Sewing School,” was part of the girls’ curriculum. These pieces of handiwork record the students’ abilities at rendering letters, numbers, and religious sentiments in needlework from a very early age. There are even a few samplers that contain images of the school itself, but the creation of these artistic renderings was strongly discouraged within a few years of the school’s founding because the Visiting Committee found them too worldly and prideful, or, as the committee’s report states, “very superfluous,” “unnecessary” and “contrary to the Rules adopted for the government of the School and the original design of the Institution.” Fortunately, the religion’s prohibitions did not apply to the making of globes, which were seen as a positive means of acquiring and sharing useful knowledge.

In an effort to “promote Teaching Geography, [and] the use of the Globes in the Girls Schools,” the Visiting Committee approved the purchase of a pair of commercially produced globes (presumably one terrestrial and one celestial) and a number of books on related subjects a little over a year after Westtown opened its doors to students. John Hamilton Moore’s The New Practical Navigator and Daily Assistant, published in 1772, and several books on astronomy by James Ferguson (1710–1776), a Scottish astronomer and globe maker, were among the books acquired by the school soon after its founding. Several copies of the 1807 edition of Benjamin Workman’s Elements of Geography Designed for Young Students of that Science were purchased a few years later. All of these undoubtedly served as useful references as the girls created terrestrial and celestial globes of their own.

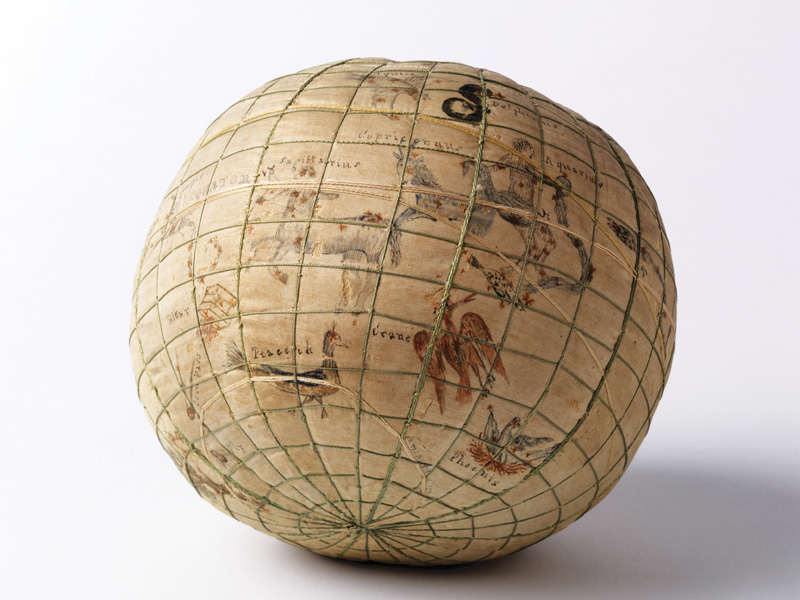

More than thirty-eight hundred girls were admitted to Westtown School between 1799 and 1843, about half the school’s total student enrollment. It is not known how many globes were created during this period, or how many have survived. The whereabouts of forty-two are currently known. They are all almost identical in size and construction—roughly 5 ½ to 6 inches in diameter, filled with raw wool, covered with linen, then silk. The details of the surfaces of each globe are quite varied, indicating the disparate interests, inclinations, and abilities of their makers.

On some of the terrestrial globes the edges of land masses are marked with stitching. On others they are outlined in ink or painted with watercolor. The treatment of geographical landmarks varies widely from globe to globe. Far more consistent are the lines representing longitude and latitude, the equator, the Arctic and Antarctic Circles, and the path taken by the sun. Some of these are marked with threads of contrasting colors for easy identification. This treatment suggests that navigation, astronomical movement, and global measurements (known as graticulation) were given every bit as much attention in the school’s curriculum as was world geography. Place names (and on celestial globes the names of stars and constellations) were carefully handwritten in ink.

Some globes contain copious amounts of geographical information. Others are sketchier in their coverage. A few have errors, but the majority are remarkably accurate in their geographical details, reflecting the findings of Captain Cook, Lewis and Clark, and other explorers in the years leading up to the globes’ creation.

Of the forty-two embroidered Westtown globes that are known to exist, five are celestial. Each is paired with a terrestrial globe made by the same hand. Although no school curriculum or set of instructions for the globe projects survive, it seems likely that all of the girls were given the opportunity to make both kinds of globes. The reason that a disproportionately small number of celestial globes was made was either because the students found the intricate renderings of stars and signs of the zodiac too challenging to capture, or because, having invested so much of their time completing their terrestrial globes, they were unable or unwilling to launch into a second embroidery project with the time and instruction available to them.

The high quality of the surviving globes, some made by girls as young as ten years old, is quite astonishing. Creating them must have been an arduous task, requiring both sophisticated sewing skills and a deep understanding of geographical (and celestial) principles. The teaching globes, from which information was extracted for use on the handmade ones, appear to have been in constant use. So much, in fact, that by 1824 it was reported that these globes had become “much defaced” and the committee on books was directed “to purchase two [more] pair[s] if it be found those in use cannot be repaired.” By January 1825, three new globes, by James Wilson in Albany, New York, had been acquired by the school, perhaps the first of American manufacture to be purchased for use at Westtown, since globes were not made commercially in the United States until 1810. Westtown would have acquired its earlier globes from England at great expense. Might the prohibitive cost of acquiring teaching globes have been one of the reasons Westtown instituted the practice of encouraging the girls to create their own?

Rachel Cope, a student who entered Westtown in February 1816 at the age of sixteen, wrote to her parents about her intention to use her own handmade globes for teaching her siblings about geography and astronomy. “I expect to have a great deal of trouble making them,” she wrote, “yet I hope they will recompense me for all my trouble, for they will certainly be a curiosity to you and of considerable use in instructing my brother and sisters, and to strengthen my own memory, respecting the supposed shape of our earth, and the manner in which it moves (or is moved) on its axis, or the line drawn through it, round which it revolves every twenty-four hours.” Her terrestrial globe is still owned by a member of her family.

Not all of Westtown’s silk globes were treated with the care they deserved. One alumna reported that a globe that was passed down through her family was used as a football by subsequent generations.

1 Minutes of the Acting Committee, May 11, 1804, Esther Duke Archives, Westtown School. 2 Ibid., October 24, 1800. 3 For an inventory and detailed descriptions and illustrations of most of the known examples, see Mary Uhl Brooks, Threads of Useful Learning: Westtown School Samplers (West Chester, PA: Westtown School, 2015), pp. 324–327. I am greatly indebted to Brooks, the school’s archivist and the author of this beautiful and thoroughly researched book, upon which I have drawn heavily for this article, for her generous assistance and enthusiastic support. There is also an inventory of known Westtown globes (as of 2015) in Judith A. Tyner, Stitching the World: Embroidered Maps and Women’s Geographical Education (Surrey, England and Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 2015), pp. 125–126. Since then, two more terrestrial globes have come to light. Readers of this article who know of globes not included in these lists are invited to contact the author (at rmp89@drexel.edu) or the Esther Duke Archives at Westtown School. 4 Minutes from the Westtown School General Committee, December 17, 1824, Esther Duke Archives, Westtown School. 5 Rachel Cope to her parents, October 15, 1816, quoted in Helen G. Hole, Westtown Through the Years, 1799–1942 (West Chester, PA: Westtown School, 1942), p. 56; and in Brooks, Threads of Useful Learning, p. 210.