How much can be done with a circle and a line? For Baltimore jeweler Betty Cooke (Fig. 1), whose mantra has always been “the simpler and clearer, the better,”1 the answer is—just about anything. Over the course of more than seven decades, Cooke has created a veritable constellation of jewelry in which the elements of design reveal their limitless capacity for innovation in the hands of a master.

The dynamic range of her career will be on view next year, when the Walters Art Museum will mount Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line to celebrate one of its city’s acclaimed female artists. Cooke is internationally renowned for her effortlessly elegant jewelry, and the exhibition will present her work in the context of her lifelong experimentation with the fundamental elements of composition. The exhibition is Cooke’s first retrospective.

The artistic seeds of Cooke’s career were sown early in life. She visited the Walters soon after it opened in 1934, when she would have been about ten years old, and the works of art she saw at that tender age left a visual impact; the upcoming exhibition will include several items—an ancient Egyptian faience hippopotamus, a metal gauntlet, and a Corot painting—that have remained among her favorites in the collection. In other activities, particularly while plein-air painting, Cooke trained her eye on the natural world. Her sharp observations in watercolor were later translated into animated owl and shore bird pins that were rendered with reductive accuracy beginning in the 1950s.

During her college years at the Maryland Institute (today Maryland Institute College of Art, or MICA), Cooke absorbed the principles of “good design.” This concept, originally based on the principles of the Bauhaus in Germany and the international style of architecture, promoted rational and functional design devoid of ornament. Influential mid-century designers like Ray and Charles Eames, Harry Bertoia, and Eero Saarinen gave humanist expression to these ideals in domestic furnishings and accessories, while a series of exhibitions called Useful Objects (1938–1949) and Good Design (1950–1955) presented at the Museum of Modern Art conveyed these ideas to the public with displays of contemporary industrial or handmade products.2

Cooke applied these precepts to her own work, and by the time she graduated in 1946, she was already selling limited-production silver jewelry expressed as pure form. On the strength of this success, she made the enterprising purchase of a house the following year on Tyson Street—then part of a bohemian neighborhood of row houses near the Walters—that was twelve feet wide by twenty feet deep. She turned it into a residence with a studio and retail shop on the first floor, and was able to meet her expenses with sales and a teaching appointment at MICA.

Word of mouth helped to expand Cooke’s business, but in order to market her jewelry beyond Baltimore, Cooke planned a western camping trip in 1948 that included stops in cities with important design galleries that she felt were more aligned with her work than most jewelry stores. Along the way, she visited the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, where Hilde Reiss, its Bauhaus-educated curator, was sufficiently impressed with Cooke’s “little box of jewelry” to include her in the landmark exhibition Modern Jewelry Under Fifty Dollars (1948).3

And so it was that when she was just twenty-three, Cooke’s jewelry shared pride of place with the country’s mid-century masters of studio jewelry, among them Alexander Calder, Margaret De Patta, Claire Falkenstein, and Art Smith. As with modern artists going back to Picasso, and including many of her peers in the exhibition, she integrated bits of found materials, such as wood or polished stones, into her jewelry, prizing design over precious materials. Those who discovered Cooke made a conscious choice to buy her studio jewelry instead of shiny costume jewelry or fashionable gold and high-carat items then popular. “People understood it,” said Cooke, “people that understand art jewelry see a different world.”4

That world was made of silver, accented with patina, wood, brass, stone, resin, and plastic. It included kinetic forms that moved with the wearer, or whose appearance could be modified by flipping elements to the reverse. From early in her career, Cooke created endless variations on the use of a circle in jewelry. One of her most enduring designs has become a series of rings with flat discs arrayed to create a sense of volume (Fig. 4). She also produced rigid neckpieces that contained fronds, or what could be called gestures, that mimicked the hand tracing a rough circle.

Cooke continued her upward trajectory in the 1950s with participation in national exhibitions such as Young Americans 1951 at America House, Good Design, 1951, at the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, and Designer Craftsmen U.S.A. 1953, at the Brooklyn Museum.5 And in the process, she epitomized the successful designer-artisan who controlled the planning and execution of her product. Her accomplishments were all the more remarkable in an age when few women were able to run their own businesses. Aside from Edith Heath (1911–2005), whose Heath Ceramics also became a thriving business, it was the rare craftswoman of her generation who experienced such noteworthy success.

With rising visibility came feature articles, such as one in Women’s Day that included jewelry design patterns for aspiring craftswomen to try out at home.6 Special praise came from designer Don Wallance in his landmark volume Shaping America’s Products (1956). He presented Cooke as a case study of the “the artistcraftsman as designer-producer,” able to scale up studio production beyond the capacity of a single artist, and whose work was imbued with “spontaneity, freshness, [and] individuality,”7 traits he believed were essential in countering the repetitive nature of mass production. Wallance ranked her among prominent woodworkers, ceramists, and jewelers like George Nakashima, Wharton Esherick, Marguerite Wildenhain, and Margaret De Patta, all senior to her by a generation.

In 1955 she married her former student, fellow MICA graduate, artist, and designer William O. Steinmetz (1927–2016), beginning a decades-long partnership in life and work. During the early years of their marriage, the couple designed interiors for restaurants, malls, and exhibitions while also maintaining their small retail space in town. In 1965 they committed to the strength of Cooke’s jewelry by opening The Store Ltd., a spacious retail store in the Village of Cross Keys, a shopping enclave in north Baltimore. They created a lively interior featuring her work alongside examples of international design, folk art, and fashion. The Store Ltd shared a zeitgeist with other showrooms of the era, including Design Research (branded as D/R) in Cambridge, Massachusetts (est. 1953, and New York City in 1961), and Alexander Girard’s Textiles and Objects gallery for Herman Miller (est. 1961) in New York City. While these iconic shops are long gone, The Store Ltd remains a mainstay in the region.

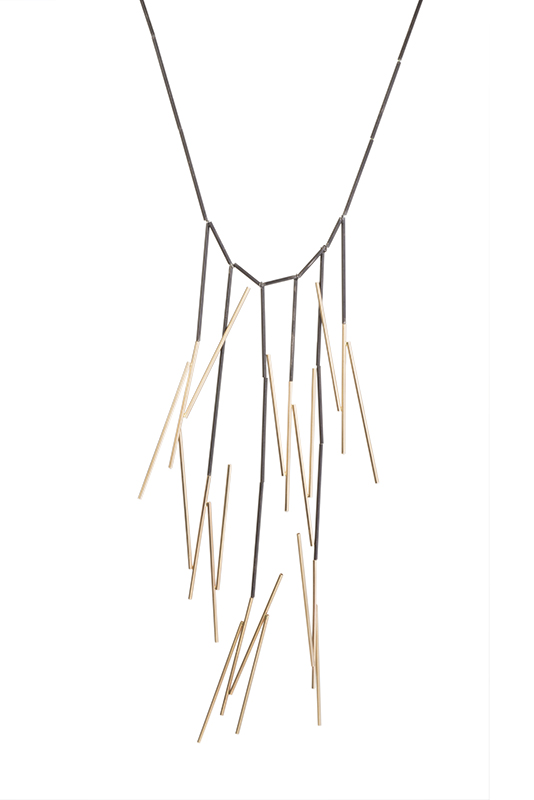

In the late ’60s, as Cooke began to think of creating larger pieces of jewelry, she hit upon the use of tubular metal in sterling silver and later in 14-karat white and yellow gold—which provided visual impact, yet was light and easy to wear. She experimented with slender tubes and cut them to different lengths, assembling various combinations, adding hanging elements she calls “tassels,” and threading them on nylon or plastic-coated thread (Fig. 3).

The resulting necklaces could be handled like delicate chains that could wrap and twist around the figure in innumerable ways, creating unexpected angles that caught the light as the wearer moved. The tubes also inspired many experiments that brought sprays of shorter tubes together in ways that resembled pine needles, or long, languorous branching necklaces that bring to mind the trees she admired long ago in Corot’s painting (Fig. 9). Using the tubular necklaces as a base, she also experimented with the infinite possibilities of what she calls “units”—such as metal discs and squares— that could be adapted and used in endless combinations with other elements.

At the Cross Keys location, Cooke played more freely with semi-precious stones. Her first inclination was to use quartz expressively in its rough, crystalized form. When tapped by Geoffrey Beene, she produced jewelry that was used by his models on catwalks and seen in magazines featuring his designs. Her quartztipped neckpieces became all the rage, and her experiments with quartz led to a lyrical neckpiece with ribbons of gold.8

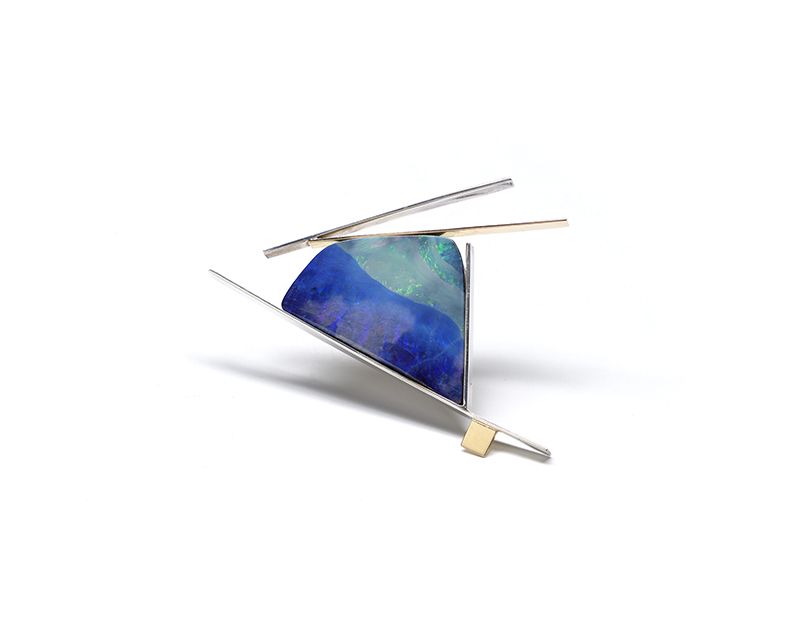

Over time, she moved toward lapidary and cabochon cuts of brilliant opal, lapis lazuli, peridot, and cool chalcedony. The shifts toward colored stones and gold reflected a similar sentiment among many studio jewelers. Despite these interests, Cooke enjoyed the play of high and low materials resulting in such pieces as a bracelet that combined a diamond with a smooth pebble—an unorthodox combination that won her a De Beers “Diamonds Today” prize in 1981 (Fig. 7).

To drop into The Store Ltd today is to find Cooke meeting and greeting visitors, many of whom are second- and even third-generation customers, whose very first piece of jewelry was a “Betty.”9 And they are back for more. Many request special commissions, and of these a still smaller group request jewelry with encoded messages.

One such customer was Jim Rouse, the pioneering urban planner and developer who was also responsible for the Village of Cross Keys, and whose offices were located directly above The Store Ltd. Beginning with his marriage to Patricia “Patty” Traugott Rouse in 1975, Rouse purchased birthday and anniversary gifts for his wife from Cooke. Each milestone posed a special challenge, for Cooke’s task was to design an ornament that cleverly disguised the number signifying these events (Fig. 10). Such requests are a powerful symbol of the close and trusting relationship that the artist has developed with her devoted clientele.

Cooke’s timeless forms and her distinctive visual vocabulary have earned her a prominent place within the canon of modern jewelry history. With a work ethic that has made her unstoppable at any age, she continues to ply her craft, creating rigorously modern jewelry for comfortable, elegant wear.

A Chat with Betty Cooke

How did it feel when you first began to work with metal?

I played and worked with all kinds of materials, and simply responded to the challenges of metal. I enjoyed creating different forms and drew with wires, although the results weren’t always certain. I made sculpture, jewelry, and objects, but jewelry offered me endless possibilities.

Give us your thoughts on design.

I came of age during what I call the design revolution, in which there was a whole new way of thinking about design, function, and appearance. That point of view made me see beauty in things as disparate as a Shaker chest, a Noguchi lamp, or a Harry Bertoia sculpture.

Please talk about your design process.

I expect that good design should be a part of all that I make. It must be attractive, functional, and original. It affects the way you see things, and helps determine how something should be built, bent, or formed, what finish it should have or what size it should be. Sometimes it happens quickly, but it can also be a more studied process. There is a joy and satisfaction in making objects that you put your whole heart and soul into. Obviously when people are pleased, it’s doubly good.

Was it a big decision to leave Tyson Street and establish The Store Ltd in 1965?

Yes, it was, but we were confident in creating a showcase for well-designed and finely crafted objects—including my own jewelry—that were intriguing and exciting to the public. Ever since we opened, we have had an influence on taste and design in the Baltimore community and beyond.

How does it feel to see your jewelry worn by your clients?

It gives me great pleasure to see jewelry worn by my customers and to hear people express their gratitude and pride in wearing work that I’ve made. And we have several generations of clients, including grandchildren. Sometimes, when we hold special events, three or four different generations will stop by all together, and that’s especially nice.

What is your advice to young jewelers working today?

Obviously, you have to love your work and enjoy having all the skills that are needed to accomplish your goals. You should also develop a substantial body of work that you can be proud of. Then it’s a personal decision as to whether you work alone as a studio jeweler or scale up your operation with assistants. I started with a solo studio and it expanded; that worked well for me. It’s also important to take part in as many exhibitions and competitions as possible, where you will find like-minded people, and a wider community that can help in so many ways. —JF

Betty Cooke: The Circle and the Line is now scheduled to open in September 2021. The exhibition catalogue is published by D. Giles Ltd. in association with the Walters Art Museum.

1Quoted in Richard Martin, Design • Jewelry • Betty Cooke (Baltimore: Maryland Institute, College of Art, 1995), n.p. 2David A. Hanks, “Spreading the Gospel of Modern Design,” Partners in Design: Alfred H. Barr Jr. and Philip Johnson (New York: Monacelli Press, 2015), pp. 174–213; 176. 3Due to Cooke’s late inclusion in the exhibition, the artist did not appear in the exhibition catalogue, but her presence was confirmed by museum staff: Joseph King, director of registration, Walker Art Center, correspondence, January 4, 2019; Jill Vuchetich, archivist, head of archives and library, Walker Art Center, correspondence, January 14, 2019. 4Betty Cooke, interviewed by Justin Sanders, February 4, 2020, Walters Art Museum. 5For a timeline of Cooke’s personal life and exhibitions, see Jeannine Falino, The Circle and the Line: Betty Cooke Jewelry (Baltimore: Walters Art Museum and Lewes, England: D Giles, 2020), pp. 44–47. 6“Collector’s Craft Book: Sterling Silver Jewelry,” Woman’s Day, April 1958, pp. 72–76. Cooke also produced designs for leather accessories, and Woman’s Day treated this subject in “The Smartest Leather Designs are the Simplest to Make” in its February 1956 issue, pp. 78–83. 7Don Wallance, “Betty Cooke,” Shaping America’s Products (New York: Reinhold, 1956), pp. 162–163. 8“Fitness Now!” Vogue, vol. 168, no. 7 (July 1, 1978), p. 117; “The New York Collections: The Clothes to Live in Now,” ibid., no. 9 (September 1, 1978), pp. 420–421. 9Nancy Rome, “Reflection,” in Jeannine Falino, The Circle and the Line: Betty Cooke Jewelry, p. 56.

JEANNINE FALINO is an independent curator and author of publications on American decorative arts, design, and contemporary craft. She specializes in ceramics, metalwork, and jewelry.