Such was its success, the Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration has been invoked any number of times since Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s day. In 1975, for example, a New York Times article proposed a new WPA for artists to help the nation recover its “spiritual strength and national pride” after the twin traumas of Vietnam and Watergate. More recently, to assist artists trying to cope with the pandemic, in August of 2021 the WPA-inspired Creative Economy Revitalization Act was introduced in the House of Representatives. That bill went nowhere, underscoring just how astounding the government’s commitment to the Federal Art Project was.

Between 1935 and 1943, the WPA put thousands of artists to work producing murals, prints, paintings, posters, sculpture, renderings, and craft pieces. While the quality of the art produced varied, the project endures as a fascinating record of the times, both socially and aesthetically. Art for the People: WPA Era Paintings from the Dijkstra Collection, on view at Sacramento’s Crocker Art Museum from January 29 to May 7, offers another opportunity to consider that era and American artists’ place within it.

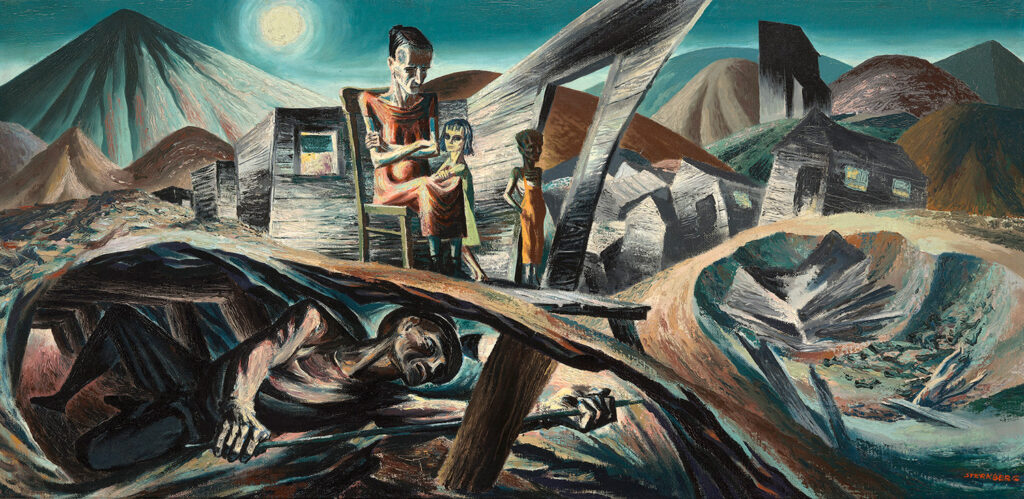

Encompassing images of people at work—or lacking it—and at leisure, as well as portraits and landscapes, the output of WPA artists was at times celebratory, at times critical. The collection assembled by Bram and Sandra Dijkstra—the former a retired university professor, the latter a literary agent—represents the full range of subjects tackled by artists working under the aegis of the WPA. As well, it includes works by artists of color, such as Charles White and Miki Hayakawa, not usually associated with the Federal Art Project.

There are curiosities in the collection: pictures that strike an individualistic note, informed less by conventional narrative than personal expression, such as Julio de Diego’s Beauty and the Beasts (1941), in which a nude woman stands almost insouciantly amid a pile of rubble and barbed wire, her gaze directed to distant soldiers and a gray sky punctuated with parachutes. And while a number of WPA artists produced realistic renderings of factories, mining, and other industries, Rico LeBrun’s Vertical Composition (1945) takes a machine-like form and presents it as battered icon.

“Looked at as a whole, the 1930s were the most socially critical period of American art, the first in which issues of social injustice, such as poverty, labor unrest and racial discrimination, were seriously addressed,” notes Scott Shields, chief curator and associate director at the Crocker. “The 1930s were also surely the most democratic period in the history of American art, due in large part to the WPA. For really the first time, the country gave voice to a vibrant racial and ethnic mix.”

The art of the New Deal was often dismissed in its day as simplistic, second rate, and propagandistic— and still is in some circles. But it is a body of work that offers a significant testament to life in tough times, and forms a revealing chronicle of the myriad ways that artists of the day tussled with the challenges of the modern world.