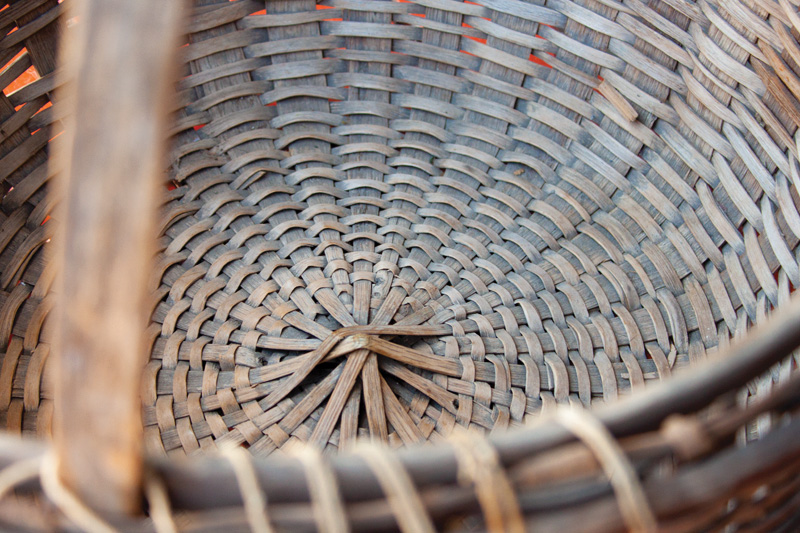

A classic example of regional folk craft, Taghkanic baskets have been woven in a small corner of the Hudson River valley since the mid-eighteenth century. Though not all do, the archetypal and most collectible Taghkanic basket has a rounded bottom with a center that pokes upward. It is made of oak and ash. The splints—a weaving term that can describe both the horizontal and vertical components of a basket—vary in width and are very strong, and the rim is lashed in a crisscross pattern. Most have either a single handle or a pair of handles, and some have a swing handle.

Taghkanic baskets are often mistaken for Shaker pieces, mixed into collections of such work, and misidentified by auction houses. While there are striking similarities, Shaker baskets were made on molds that guaranteed uniformity, while Taghkanic basketmakers used only visual models and muscle memory as guides. This increased the variation in form and weaving pattern—working with thinner splints, smaller, nimble hands could do more detailed work—and allowed for more creativity and invention.

The baskets were made for heavy use, and they became good business for the small group of families—the Propers, Snyders, Hotalings, and Simmons—that crafted them on “the Hill,” a once-isolated area to the west of Route 82 in Gallatin, New York. What brought the families to that location, heavily wooded and ill-suited to cultivation, is contested. Some pin it on the guerrilla-style rent wars of Livingston Manor in 1766, and again in the mid-nineteenth century—a place of refuge when tenants rose up in defiance of the near-feudal conditions imposed by the great landholders of the region. The Proper family’s oral history suggests their early nineteenth-century forebears were pulled toward a life not tied to the rigors of agricultural labor. (Although basketmaking with hand-hewn timber can hardly be called unrigorous.)

If the goal of living on the Hill was solitude and solace, they picked the perfect spot to resettle. A 1798 map shows many families carrying the basketmakers’ names in the region around Lake Charlotte, now Lake Taghkanic State Park. The lake’s outflow empties into the Roeliff Jansen Kill, a creek that served as a major conduit for market goods. Earning a living on poor land required an alternative form of subsistence—which is how the baskets transformed from a useful tool into a marketable product that in time formed a connection to the outside world. Styles were developed and refined to fit the intended uses, and it has been said that members of nearby native tribes advised the Hill families on refinements. (“Taghkanic” is transliterated from a term used by the Lenape natives for the region, meaning “forest.”)

As time passed, the surrounding communities spun their own stories around the Hill’s inhabitants. “Everyone blamed the people on the Hill for everything,” Maryann Barto remembers her mother, Elizabeth Proper, the last of the Taghkanic basketmakers, telling her. “If their cheese curdled when it wasn’t supposed to,” they blamed it on “witchcraft from the Hill.” But come harvest season they still bought baskets.

Barto learned by watching her mother weave, just as her mother had watched those before her. It was the 1970s, the basketmakers had dispersed from the Hill, and curious collectors had begun seeking out the hand-painted sign outside their home along Route 82.

As with much of their history, even the name for the baskets is disputed. Nathan Taylor and Martha Wetherbee, co-authors of Legend of the Bushwhacker Basket, insist that “Bushwhacker” is the proper name—a way to reclaim a term that was applied to Hill families in a derogatory sense, akin to “hillbilly.” Barto recoils at this. She sees no need to embrace any such identity. They are Taghkanic baskets, she insists, full stop.

In a private sale, a Taghkanic basket with a round bottom, without significant damage, measuring ten inches across or more, can go for, Wetherbee and Barto agree, $1,200 or more. Minor damage that doesn’t impact the overall aesthetic reduces the value by 20 or 30 percent, as does a finish. A well-worn basket held together with string may not be much good for carrying loads, but it can still sell for a few hundred dollars. At auction, prices have varied wildly, from a few hundred dollars to far more.

While a comprehensive reconstruction of the history of the baskets is likely impossible, there remain particulars upon which all agree. They are unique works of functional art that can be fixed to a particular place and time, wrought with ingenious craftsmanship by a small number of skilled hands hard at work. In this, they are spectacular. There seems to us no higher praise we can give.