Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery through Reconstruction by Aaron Douglas (1899–1979), 1934. Signed “A. DOUGLAS” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 60 by 139 inches. Except as noted, the objects illustrated are in the Art and Artifacts Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Gift of the W.P.A.

The ashes of poet Langston Hughes are interred in Harlem at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, a unit of the New York Public Library. They lie in a bookshaped receptacle buried beneath a magnificent work of art: Rivers, a 1991 terrazzo and brass installation—designed collaboratively by sculptor Houston Conwill, his sister, poet Estella Conwill Majozo, and architect Joseph DePace—that covers the floor of the library’s theater lobby. Inspired by the Hughes poem “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” (1921), the artwork features lines of verse, geographical references (such as the veins of azure that represent rivers—the Euphrates, the Nile, the Mississippi—central to black cultural anthropology), and runes and symbols related to sacred, ancestral Kongo art and ritual.

The floor of the Schomburg Center features Rivers by Houston Conwill (1947–2016), Estella Conwill Majozo (1949–), and Joseph DePace (1954–). Terrazzo and brass, 50 by 21 feet. Commissioned by the Schomburg Center.

Rivers is both a tribute and a complement to Hughes’s literary achievement, and as such neatly embodies the unique character of the Schomburg Center: it is a temple to the written word that is also a shrine to the visual arts. While the center is a key resource for scholars of African American history and culture, it is also the sole branch of the NYPL with an active arts acquisition program.The center’s Arts and Artifacts Division lays claim to one of the “most comprehensive collections of black artists’work in a research center,”* comprising some twenty thousand objects including paintings, sculpture, and works on paper. Its Photographs and Prints Division has a collection of more than ve hundred thousand works.“The Schomburg Center is not only an unsurpassed research facility, it also has an art collection singular in its focus and commitment,” says Catherine Morris, senior curator of the Brooklyn Museum’s Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. “Loans from the Schomburg have played pivotal roles in numerous projects here.”

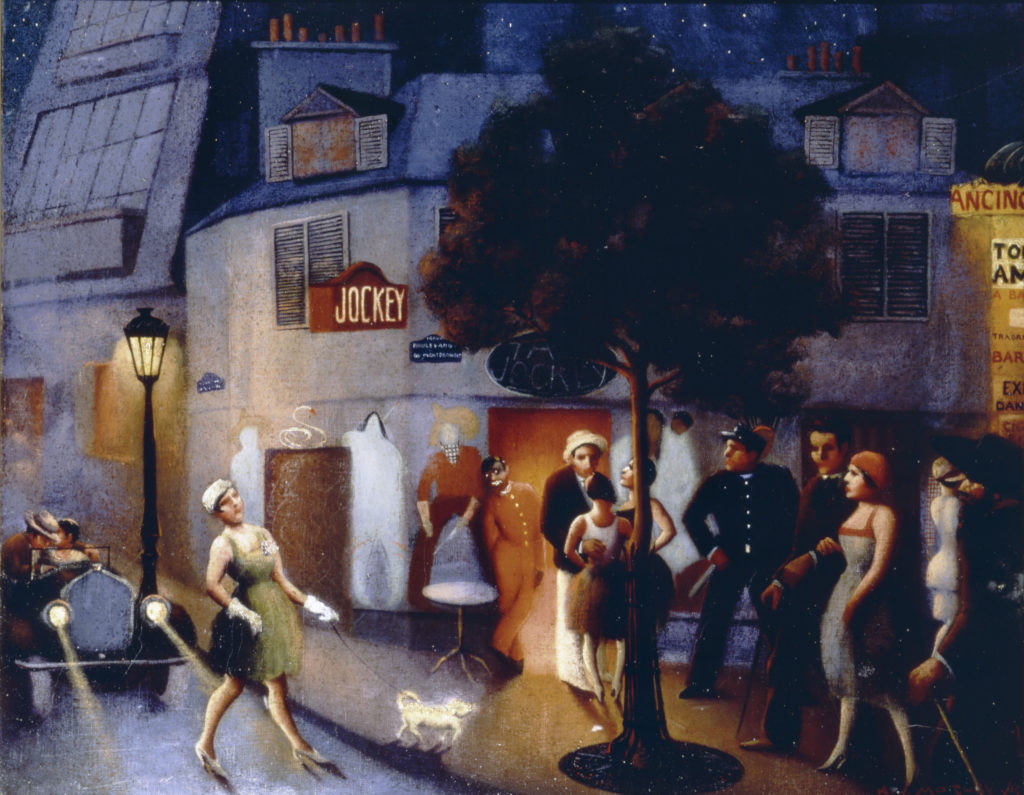

Jockey Club by Archibald J. Motley Jr. (1891–1981), 1929. Signed “A.J. MOTLEY JR.” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 37 ½ by 32 inches. Gift of Alice Mollison.

The Schomburg Center began life in 1905 as a Carnegie-financed branch library on 135th Street with ten thousand volumes, housed in an Italian Renaissance palazzostyle edifice designed by Charles Follen McKim—now known as the Landmark Building and one of three that comprise the center. As the area’s demographics changed, the library shifted emphasis toward material of black historical and cultural interest, and by the early 1920s it was a popular meeting spot for artists, writers, and polemicists. The library took concrete shape as a cultural research center when it acquired the vast personal collection of books, manuscripts, artifacts, and ephemera compiled by the Puerto Rican–born scholar and activist Arturo Alfonso Schomburg (1874–1938) for $10,000 in 1926. The collection became the basis of the library’s Division of Negro Literature, History and Prints, and the institution was renamed in his honor in 1940.

Arturo Schomburg also planted the seeds for today’s art collection. Two of the oldest works among the center’s holdings are a pair of mid nineteenthcentury bronze portrait busts that Schomburg acquired in Europe, African Venus (1851) and Said Abdullah (1848), modeled by French artist Charles Henri Joseph Cordier. Inspired by France’s formal abolition of slavery in its colonies in 1848, Cordier embarked on a series of ethnographic sculptures of people from Africa, the Middle East, and Southern Europe to demonstrate his concept of the universality of beauty.

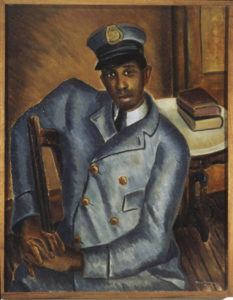

Postman by Malvin Gray Johnson (1896–1934), 1934. Signed and dated “Gray Johnson/ • 34•” at lower right. Oil on canvas, 37 ½ by 30 inches. Gift of the W.P.A.

The Schomburg Center’s art collection holds pre dominantly twentieth-century works, and is particularly rich in art from its early decades. Two of the most important holdings are a plaster model and a bronze cast of Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller’s 1914 sculpture Ethiopia Awakening. The Philadelphia-born Fuller studied in Paris and became recognized as a protégée of Auguste Rodin. Ethiopia Awakening is an allegorical figure inspired by Pan-Africanism—a movement born in the nineteenth century built around the idea that people of African descent should unite globally in common cause. Fuller depicts Ethiopia as a woman, who symbolizes Africa at large, emerging from slumber and breaking free of the pharaonic headwear and mummy wrappings of Egypt—the part of Africa that had long been the object of most historical and cultural interest to the Western world to start a new life.

Lift Every Voice and Sing (The Harp) by Augusta Savage (1892–1962), c. 1939. Inscribed “Augusta Savage WORLDS FAIR 1939”

on base. Cast white metal with bronze patina; height 10¾, width 9½, depth 4 inches. An example of this piece is in the Schomburg Center’s collection. Photograph courtesy of the Swann Auction Galleries.

Fuller and the ideas that informed her work helped pave the way for the cultural efflorescence known as the Harlem Renaissance. That widely influential movement involved all the arts, as writers, painters, sculptors, musicians, actors, and others sought to forge a new identity for black Americans, unencumbered by white stereotypes. The Harlem Renaissance is generally dated from the late 1910s to the closing years of the 1930s, and many of the most significant works in the Schomburg Center collection are from that period.

They include Malvin Gray Johnson’s Postman, a dignified portrait of a workingclass subject typical of the artist’s work. Another is Jockey Club by Archibald Motley Jr., one of the vividly hued, energetic nightlife scenes for which Motley is best known. And there is the gem of the collection: the four murals known collectively as Aspects of Negro Life by Aaron Douglas. Commissioned for the library by the New Deal’s Public Works of Art Project in 1934, the panels depict a sweeping narrative of the black experience in Africa and America, rendered in Douglas’s in imitable style employing tonal gradations, stylized silhouettes, and geometric forms.

Untitled (Man with Mule) by Bill Traylor (c. 1854–1949), n.d. Tempera on board, 23½ by 14¼ inches. Gift of Robert Douglass.

The Schomburg collection boasts works by some of the most famous black artists of the twentieth century. It includes The Curator (Arthur A. Schomburg), a marvelous 1937 portrait by Jacob Lawrence; a temperaon-board painting—depicting a man riding a mule—by the great Alabama-born self-taught artist Bill Traylor; and a powerful polychromed wood sculpture, Political Prisoner, by the activist and artist Elizabeth Catlett. The collection also contains work by some who should be better known. One of these is Augusta Savage, whose personal archives the Schomburg Center owns. The Florida-born sculptor studied at the Cooper Union and in Paris, and became an influential educator in Harlem—Jacob Lawrence was one of her students — through her own teaching studio and as director of the Works Progress Administration’s Harlem Community Art Center. Savage was commissioned to create a monumental sculpture for the 1939 World’s Fair on the theme of “The American Negro’s Contribution to Music, Especially to Song.” Inspired by James Weldon Johnson’s 1899 poem “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” she created a sculpture of the same name (though it is more commonly referred to as The Harp). Its central figures are a group of choir singers, arrayed at graduated heights that together make the shape of a harp.The sixteen-foot-tall sculpture was cast in plaster for the fair and given a dark patina. A number of small replicas were cast in metal and sold as souvenirs (the Schomburg Center has one), but the original was destroyed at the close of the fair.

The Curator (Arthur A. Schomburg) by Jacob Lawrence (1917–2000), 1937. Signed and dated “J•Lawrence 37” at lower left. Oil on canvas, 11 by 8½ inches. Gift of Peter Putnam.

The center’s Prints and Photographs Division contains an even deeper mine of material. Its holdings range from slave dealers’ handbills and scenic engravings to nineteenth-century cartes de visite and motion picture stills.The lives of Harlem residents are captured in images that range from James Van Der Zee’s elegant studio portraits to the joyful, hectic street scenes of the twin brothers Morgan and Marvin Smith. Perhaps the most moving photos in the Schomburg Center’s collection are those documenting the world of sharecroppers in the South, taken during the years of the Great Depression by such luminaries as Dorothea Lange and Ben Shahn.

Political Prisoner by Elizabeth Catlett (1915–2012), 1971. Cedar; height 71½, width 19½, depth 12 inches. Gift of Peter Putnam.

Changes for the good are apparent at the library. Earlier this year, the Art and Artifacts Division revealed the results of a renovation that was part of a $22 million capital planning project for the center. “I’ve gained eight hundred percent more storage space in one collection area and three hundred percent more in an other. My storage shelving and racks are compact now to maximize space,” says the division’s associate curator, Tammi Lawson. “Everything is state of the art. I have Italian cabinetry and my display cabinets have their own airtight system that keeps chemicals and pollutants out. Our twenty-foot windows have UV filters, vapor barriers, and blackout shades. I have beautiful oversize marble tabletops for my patrons to do research on.”

Sounds like a good time to visit. Duke Ellington swore by the A train, but we recommend the 2 and 3 lines. The station is right across the street from the Schomburg Center.