Philadelphia joiners and cabinetmakers of the mid-eighteenth century mastered the design of the high chest—essentially a chest on top of a table with drawers unique to colonial North America by the 1740s. Crowned by pediments that referenced architecture (the basis of furniture makers’ patterns), high chests were monumental but elegant, and their surfaces became the canvas for the carver’s art. This high chest’s outline, molding profiles, proportions, and carving place it stylistically between the earliest high chests with turned or bandy cabriole legs and the more complex, ornately carved monuments of the late colonial period. The corners of the upper case have quarter columns fluted in the familiar fashion, while those on the lower case are, unusually, completely smooth. A pair of eye-brow-shaped elongated arches form the lower front rail.

While not as fussily embellished as others, this high chest’s significance to the patron who commissioned it is suggested by the choice of mahogany, a tropical hardwood imported into Philadelphia, probably from one of the numerous Quaker-owned Caribbean plantations worked by enslaved people. Carvers preferred working with mahogany’s smooth tight grain, and the robust articulation of the carving on the high chest demonstrates mahogany’s facility under the chisel. The central drawers on the upper and lower cases and the scrolled pediment—with a central “shield” (later named a cartouche by collectors) flanked by “blazes” (or finials)—were likely carved by one of the dozens of London-trained artisans working in Philadelphia. A high chest (along with its matching dressing table) in the Garvan Collection at the Yale University Art Gallery nearly matches this one; it was likely made by the same joiners, and both were probably carved by the artisan now known only as the “Garvan carver.”

A trio of shell carvings—in the carved shield, tympanum, and central lower drawer—became standard on Philadelphia high chests, and much ink has been spilled both describing and sorting out the potential meaning of those elements. As part of my research into the domestic landscape of the eighteenth-century patron, I offer up a potential new meaning—one that acknowledges nature as the muse of both artisans and, especially in colonial Philadelphia, patrons.

Early colonists were more in sync with the natural world than we are today. The natural resources of the Penn family’s proprietary colony of Pennsylvania (quite literally Penn’s Woods) fueled the success of the port of Philadelphia, which permitted early owners of this high chest, Adam (1741–1817) and Elizabeth Hartman Kuhn (1755–1791), to live like aristocrats. In the colonists’ for-mer homes in Europe, the Pecten maximus—known as the great scallop, king scallop, or Saint James scallop—is common in the North Atlantic from Norway south to Spain, and its meat was a significant food source that was also used to provision ships. Once here, colonists would have been mostly deprived of such scallops in their diet, but fossils of various Chesapectens continued to arouse colonists’ interests in nature’s bountiful shells. The prominence of the scallop shell in porcelain pickle stands must also be viewed in this context. Unlike at English manufactories, the modelers at Bonnin and Morris’s manufactory in Philadelphia used actual scallop shells to mold their dishes.

In Britain, Ireland, and Europe the scallop shell motif appears on architectural friezes, as well as the knees, crest rails, table rails, and tympanums of furniture. But nowhere is it more pronounced than on furniture made in colonial North America. In Philadelphia the furniture maker and carver gave the scallop shell’s beauty a degree of reverence.

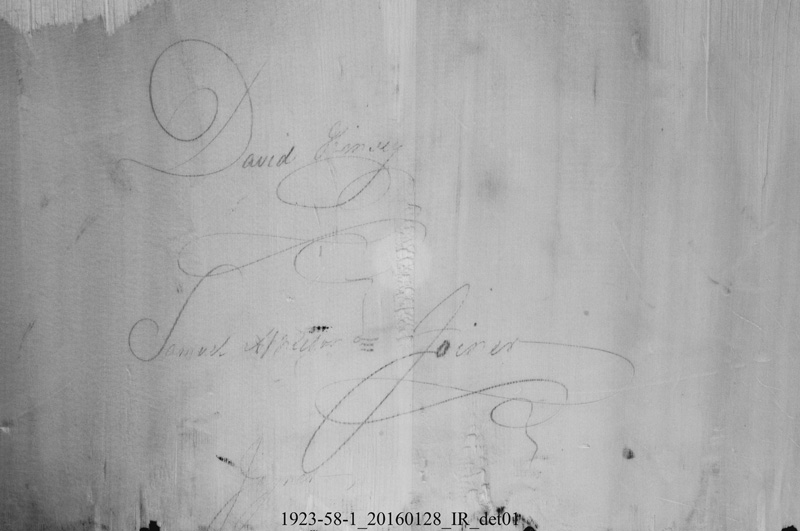

This high chest, signed by the Quaker joiners David Kinsey and Samuel Appleton, served as a prototype for a group of furniture with related front rails and construction produced by the network of Quaker joiners and cabinet-makers working in colonial Philadelphia. Fresh from a conservation treatment completed at the PMA in 2017 by former American furniture catalogue project conservator Gert van Gerven, the high chest’s shell carvings became more visible, offering a new understanding of their iconography. In my opinion, they illustrate the complete anatomy of the scallop: on the tympanum, an applied carving of its fringed interior membranes; on the shield, the roe represented in the cabochon shape (which collectors often call the “Philadelphia peanut”); on the central drawer, a relief-carved concave, interior view of the shell with its articulated pattern of lobes and mottled surface flanked by applied exaggerated wings, or ears, that form the square base of a scallop shell.

So what motivated colonial North Americans’ obsession with the scallop, shell and all? Was it an expression of their desire for a food they would have been less frequently able to eat? Or was it simply admiration for nature’s decorative potential? Further study into the literature and writings of the 1730 to 1770 period may elucidate this, but until then the depiction of the scallop on Philadelphia furniture should be understood as representing more than just its shell.

Joiner John Kinsey had a greater impact on Philadelphia cabinetmaking than has ever been acknowledged. He descended from an important Quaker family of joiners in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, that included the prominent Philadelphia cabinetmaker Benjamin Randolph (1737/38–1791), his cousin. After working with fellow Quaker joiner and carver Henry Clifton (1725–1771), Kinsey became the leading member of a partnership of four joiners: himself, Appleton, Joseph Lancaster, and John Folwell (1732–1780). The advertisement in the Pennsylvania Gazette that announces the dissolution of their partnership on September 19, 1765, refers to the group in shorthand as “Kinsey and Company.” Kinsey married Gaynor (Gainor) Evans Bartholomew, the widow of tanner John Bartholomew, at Gloria Dei Church (Old Swedes’) on August 21, 1766, at which time he was disowned by the Quaker meeting for being married by the “hireling priest” Charles Magnus Wrangel (c. 1730–1786). Kinsey worked as a joiner until his death in 1779. While this is the only known example of a work signed by him, he appears to have been central to the network of Quaker cabinetmakers and joiners working in mid-eighteenth-century Philadelphia. With this early and robust high chest touchstone and the significance of his family and partners, the opus of Kinsey’s furniture should broaden, and he deserves to be recognized as belonging to late colonial Philadelphia’s pantheon of eminent furniture artisans.