Glasgow tearoom entrepreneur Miss Catherine Cranston was acutely market-savvy. Over a forty-year period she built up a successful and respected city-center business empire in Scotland’s industrial heartland, opening her first premises in 1878, her last in 1917. She cut an instantly recognizable figure, wearing out-of-fashion mid-Victorian-era dresses, yet she employed young local designers working in a cutting-edge aesthetic to shop-fit and decorate the interiors of her four tearoom buildings. A proponent of the temperance movement, Catherine Cranston’s unique business proposition—in today’s entrepreneurial parlance—was to provide diners with inspirational, and aesthetically and artistically hip, places to take tea and lunch—spaces designed in the Glasgow Style, Britain’s only distinctive response to art nouveau.

Cranston’s old-fashioned self-branding mixed with her patronage of “New Art” Glasgow design was magic. Most important was her significant patronage, between 1896 and 1917, of architect, designer, and artist Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Her tearoom commissions gave Mackintosh the freedom to experimentally develop his visual language and imagination. In return, he gave her fantastical decorative interior design experiences, the likes of which could be seen nowhere else in the world.

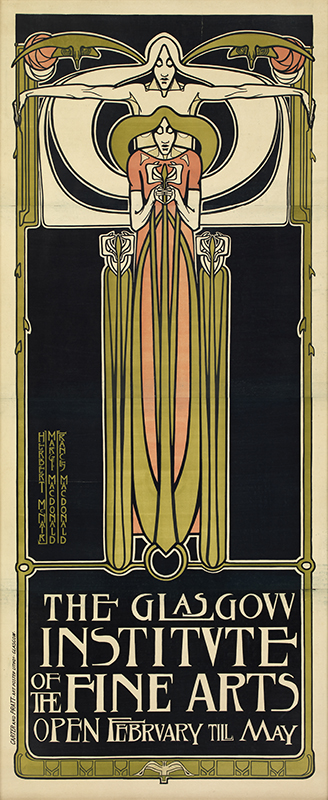

Initially, Mackintosh was brought in to work alongside the established Glasgow interior designer George Walton on Miss Cranston’s new four-story tearooms on the busy thoroughfare of Buchanan Street. Walton specialized in elegant patterned wall coverings, painted murals, leaded colored glass panels set with repoussé copper, and furniture designs of either a solid arts and crafts style or an attenuated spin on Regency and Queen Anne forms. He had set up his company in 1888, producing his first interiors for Cranston that same year. Mackintosh’s appointment may have been because, by the summer of 1896, he and his close circle of friends—James Herbert McNair and sisters Margaret and Frances Macdonald, collectively known in artistic circles as the “Glasgow Four” (see Fig. 4)—had already made a controversial name for themselves. Their highly symbolic watercolors of androgynous humans and stylized plant forms exhibited in Glasgow in 1894 had created ripples, leading the press to call their work the “Spook School.” Their Aubrey Beardsley–inspired figurative posters from early 1895 were similarly derided, but however derogatory the locals were about their highly stylized graphic art, it got the Four noticed internationally. They exhibited their posters in December 1895 at the first exhibition in Siegfried Bing’s gallery La Maison de L’Art Nouveau in Paris, and again in London in 1896 (Fig. 7). A two-part feature on their work was published in The Studio in 1897.

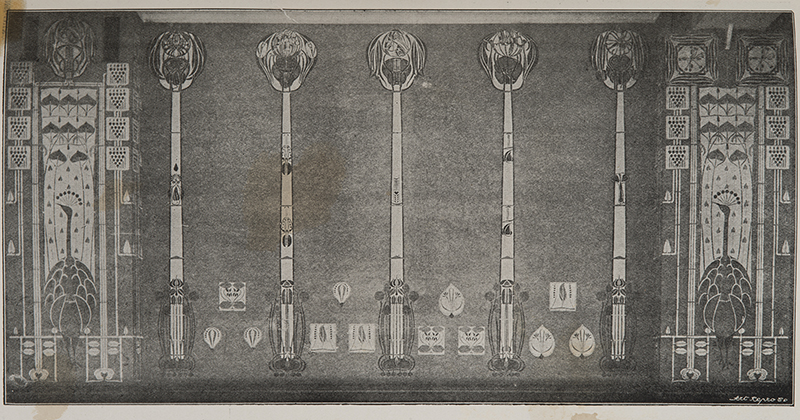

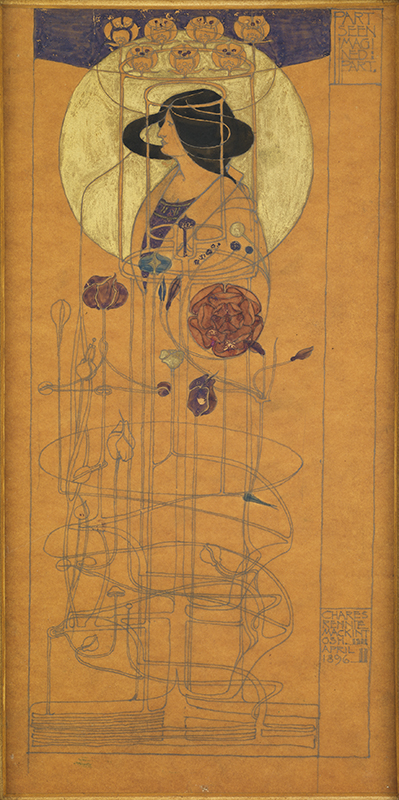

The Buchanan Street Tearooms opened on May 5, 1897. Drawing from his poster art stylizations, Mackintosh contributed three bold stenciled mural schemes, only a small part of the tearooms’ overall decoration. Each mural was visually distinct, but all were linked by a harmoniously thought-out color scheme. One room featured a wall stenciled with peacocks in a mysterious plant- and tree-filled landscape set against a background of deep green (Fig. 3). Some of the stencil cards used for the treetops in the mural survive, made by decorators Guthrie and Wells—the component parts of their design drawing on Japanese family crests and botany (Fig. 2). Another tearoom saw an ethereal procession of kimono-clad art nouveau ladies, each emerging from a tangle of rose briars set against a background of gray-green-yellow. This design was based on Mackintosh’s drawing of a single figure entitled Part Seen, Imagined Part, exhibited at the Arts and Crafts Exhibition in London in April 1896 (Fig. 5). The last room he decorated, at the top of the building, was a smoking room. Of all Mackintosh’s decor, this was the most Beardsleyian in reference; a sad-looking moon and abstracted stylized foliate forms—some of which resembled male genitalia—are set against a blue background. The English architect Edwin Lutyens, a regular visitor to the tearooms, described the decor as “gorgeous and a wee bit vulgar.”

Walton was responsible for the overall interior design for Miss Cranston’s 1898 five-floor Argyle Street Tearooms; Mackintosh was given the task of designing the freestanding furniture. Here, Mackintosh conjured some of his most distinctive pieces of dark-stained oak furniture, and his most iconic—and first—high-backed chair design (Fig. 6). The chair’s oval headrest frames the sitter with an elliptical nimbus—and is pierced with an outline suggesting the silhouetted arced wings and body of a stylized flying bird. Created in 1898, the chair is so timelessly modern that it has been used by set designers since the 1980s as a representation of the future—appearing in films and television productions such as Blade Runner and Star Trek: The Next Generation. The starting point for this radical high-backed chair design was possibly the act of tracing illustrations of William and Mary or Dutch late sixteenth- and seventeenth-century examples, stripping away the fussily carved surfaces and simplifying the forms. Similarly, for his next high-backed chair, designed in 1900 for the Ingram Street Tearooms (Fig. 8), Mackintosh chose to simplify and severely elongate the back, piercing the tall, central splats with specifically placed squares to lead the eye upward.

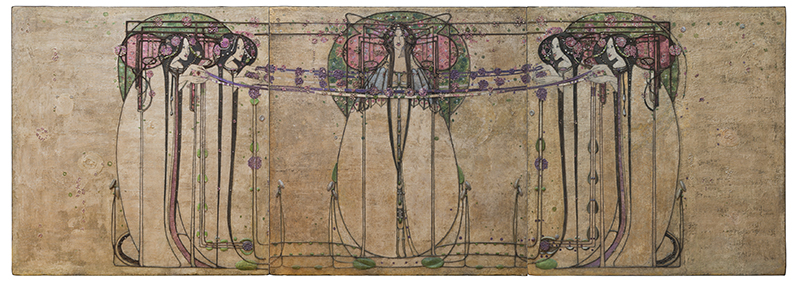

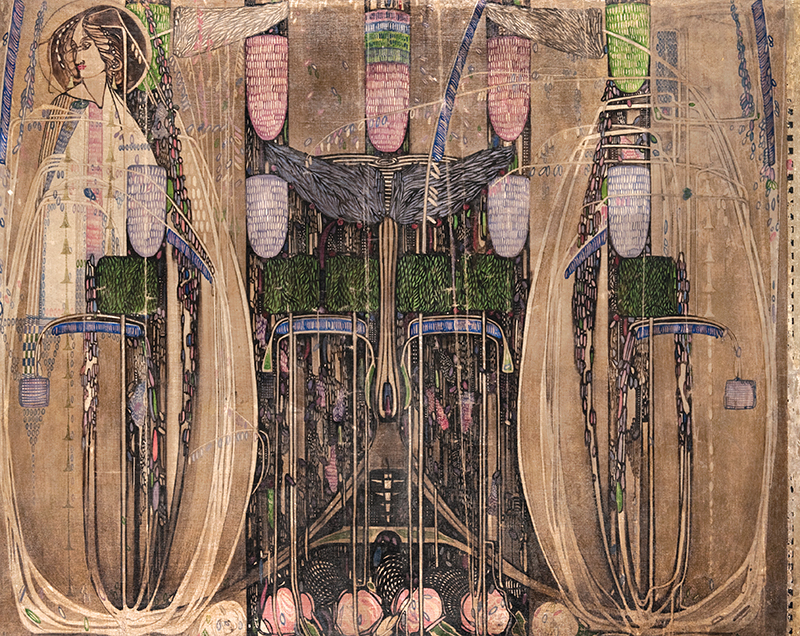

From 1900 on, Mackintosh was the sole designer for Catherine Cranston’s tearooms. His interior aesthetic of unified, harmonious, pared-down simplicity gave her customers a truly modern dining experience. For her Ingram Street premises (her first non-Mackintosh rooms had opened there in 1886), he created his first white-painted tearoom, the Ladies’ Luncheon Room, which was strikingly decorated with two fifteen-foot-long figurative gesso friezes: The Wassail by Mackintosh and The May Queen by his wife, Margaret Macdonald (Fig. 1). The colorful panels faced each other high up on opposing walls—the theatrical concept perhaps derived from Mackintosh’s grand tour of Italy in 1891, where he saw the bright, figurative Byzantine mosaics in the basilicas of Ravenna. When seen close up, the homemade nature of their construction is clear: the lines are drawn with painted string (held fast into the wet gesso with steel pins), textures are created by modeling the plaster, adding beads, oil paint, and tin leaf.

In 1903 Mackintosh transformed an existing building on Sauchiehall Street into his most luxurious suite of tearooms for Miss Cranston: the Willow Tea Rooms. Opened on October 28, the premises wowed the local press, which lavished superlatives over Mackintosh’s design. It was at the Willow that Mackintosh moved from devising a single tearoom interior formed by a number of two-dimensional art nouveau components to creating a sophisticated and complex three-dimensional Gesamtkunstwerk—a suite of conceptual interiors rendered whole by combining furniture, accessories, fittings, colors, materials, abstract shapes, and figurative elements to create a total work of art. Chairs, often ebonized or stained dark, became sculptural pieces of architecture set at specific points within the dining space.

“Sauchiehall” translates from the Gaelic as “alley—or meadow—of willows,” giving Mackintosh the willow tree as the concept for these tearooms; he could draw upon its symbolism, myth, and myriad leaf shapes and colors. Such variety across the component parts is evident when looking down into the ground-floor front luncheon room from the main staircase (Fig. 11), where you can see glass beads threaded onto metalwork, embroidered textiles, and cast and carved relief detailing along the walls. In the second-floor Room de Luxe—lined with mirrored and colored glass panels—diners paid a penny extra to sup under the two magnificent glass-drop chandeliers and sit at furniture finished in painted aluminum. There were two focal points in this room: the piped- gesso panel by Margaret Macdonald, O Ye, All Ye, that Walk in Willowwood (Fig. 13), depicting the forest’s ghostly apparitions and grief described in a sonnet by the Pre-Raphaelite poet and artist Dante Gabriel Rossetti; and the largest pieces of leaded glass Mackintosh ever designed, the magnificent swing doors that diners passed through to enter the room (Fig. 12).

By this time Mackintosh was at the peak of his design powers, devising his most accomplished and sophisticated buildings: private commissions such as his domestic masterpiece Hill House in Helensburgh (1902–1904), and public buildings such as Scotland Street School in Glasgow (1903–1906). Ideas and experimentation are sometimes evident linking his tearoom designs with these other architectural commissions. The most important of such design interrelationships lies between his largest tearoom interior at Ingram Street, the forty-seven-foot-long Oak Room of 1907–1908, and his acknowledged interior masterwork, the magnificent library created as part of the second phase of the Glasgow School of Art (1907–1909).

The Oak Room (Fig. 10) has an underlying musicality and rhythm, largely achieved by the regular vertical placing of wooden panels around its perimeter walls, and a quicker spacing of thin vertical balusters for the central staircase and stair screen. Most noticeably, the room has an abundance of light. Daylight arrives through two glazed external walls; and a spectacular number of electric lamps—forty-eight, a definite design statement—atmospherically illuminates the room in darker hours. Vibrant touches of color were added to the warm dark-stained wooden interior through blue- and indigo-enameled opalescent glass and pink and blue translucent glass. Mackintosh constructed a mezzanine level around three sides, creating two distinct dining zones. The upper level is illuminated by light fittings with teardrop-shaped shades made of blown uranium glass; the ground floor is lit by trapezoidal lampshades of leaded pink and blue flashed glass. This perimeter arrangement allowed the center of the room to be dramatically experienced as a full-height space. Visual exaggeration was achieved through the employment of single wooden posts that branched upward and outward from floor to ceiling, giving the impression of this space as a tree-lined glade. Latticed brass lampshades illuminated the central area, each suspended in front of waves of wood lathe affixed to the balcony balustrade, the juxtaposition of the rippled metal and wood casting diagonal rays of light and shadow.

An exacting spatial geometry coupled with his distillation of ideas sourced from nature and Japanese art, and his fascination with color, lighting, and shadow, now informed the core of Mackintosh’s work. They were combined most effectively in his blue-painted wooden Chinese Room (Fig. 15), built into Ingram Street in 1911. Gridded screens lowered the ceiling to create intimacy; simplified Asian-inspired decoration—such as angular curls of clouds —was cut and carved into the tops of the cash desk and door canopy and stepped devices cut into the seat frame of the room’s ebonized chairs (Fig. 14). Green and red were brought in through the painted pagoda-topped pendant lamps and finials, and via strips of colored casein plastic, leaded together and inset into the room’s wall paneling. These alternated with leaded panels of mirrored glass, which bounced reflected light deep down into the room.

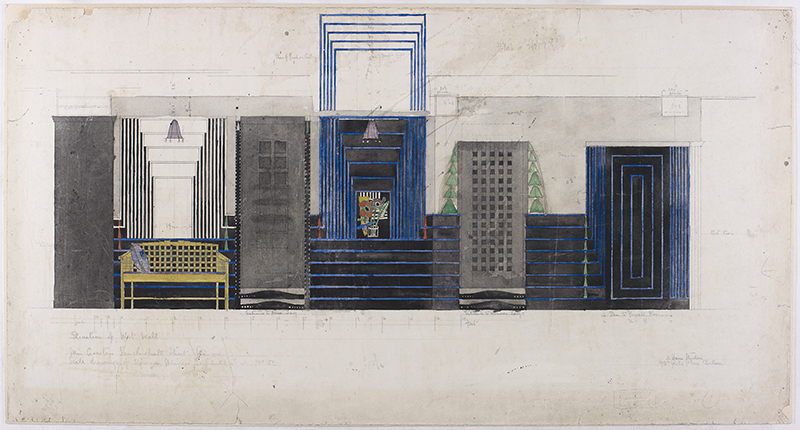

Mackintosh’s last two tearoom interiors for Miss Cranston were dramatically bold and colorful, demonstrating how his ideas were moving into explorations of rhythmic pattern. Both rooms anticipated art deco long before the term was coined at the Paris International Exhibition of 1925.

The Cloister Room of 1912 at Ingram Street was the last tearoom (actually, a men’s smoking room) Mackintosh completed before leaving Glasgow in 1914. The feature wall panels (Fig. 18) were stepped constructions, stenciled with a wave motif that was heavily employed around the room: above doorways, along the cornice, carved and cast into the barrel-vaulted plaster ceiling, and wrought in iron for the umbrella baskets. The far end of the room contained illuminated mirrored niches fronted by carved geometric fretwork, providing an exotic hint of Marrakesh.

The Dug-Out, a basement extension to the Willow Tea Rooms, was completed in 1917 (Fig. 17). Here, Mackintosh used decorative paneling devices similar to those employed in his 1911–1912 Ingram Street rooms. Bright color, such as the yellow-painted settle, compensated for the small rooms receiving little natural daylight. Its name, the Dug-Out, referenced the trenches cut by soldiers fighting on the front line in Europe. Many men from Glasgow were fighting in World War I, and many had already lost their lives; a fireplace Mackintosh designed for the tearoom acted as a memorial to the Great War. And for the first time since 1903, Mackintosh brought a figurative element back into his tearoom designs: his only known oil paintings, two elaborate, almost identical canvases (Figs. 16a, 16b). In making these, Mackintosh seems to have drawn on the symbolic figurative scenes he and his wife had painted and crafted since the mid-1890s, and on his earlier interiors for Cranston: figures emerging from plant forms (Buchanan Street, 1897), seasonal ceremonies linking humans to the cycle of nature (the Ladies’ Luncheon Room, 1900–1901), and the otherworldly spiritual plane suggested by details of leafy forests, weeping willow trees, and roses (the Willow Tea Rooms, 1903). Possibly these canvases were designed to accompany the memorial fireplace, the two painted figures looking on compassionately as monumental saintly guardians or angels in a sacrosanct space.

In 1917, the same year that the Dug-Out opened, Catherine Cranston’s husband, John Cochrane, died. Aged sixty-eight, she quickly dismantled her empire. By 1918 both the Buchanan and Argyle Street Tearooms had closed; the Willow Tea Rooms became The Kensington in 1919, and, later, part of Daly’s department store. The Ingram Street Tearooms remained operational under different owners until the early 1950s, the interiors documented and dismantled in 1971 and transferred to the collections of Glasgow Museums. In 1934, six years after Mackintosh’s death, Catherine Cranston died. She was eighty-five. Numerous obituaries noted a deep regret that her passing marked the end of an era.

Designing the New, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow Style, co-organized by Glasgow Museums and the American Federation of Arts, is on view at the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (October 6–January 5, 2020), the Frist Art Museum, Nashville, Tennessee (June 26–September 27, 2020), the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement, St. Petersburg, Florida (October 29, 2020–January 24, 2021), and the Richard H. Driehaus Museum, Chicago (February 27–May 23, 2021).

Alison Brown is curator of European Decorative Art and Design from 1800 at Glasgow Museums and curator of the traveling exhibition Designing the New, Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow Style and author of the accompanying book, Charles Rennie Mackintosh: Making the Glasgow Style, published by DelMonico Books.