It wasn’t until I began talking to David Pilgrim about his Jim Crow Museum at Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, that I thought I finally understood Juneteenth, the novel that Ralph Ellison worked on for decades, leaving it unfinished at his death in 1994. (An edition of the sprawling manuscript was issued in 1999.) Decades before that, the Black power movement of the late 1960s had already pushed the author of Invisible Man to the margins of the struggle. Although he was sympathetic to their cause, the elegantly dressed and overwhelmingly eloquent Ellison gave no ground to either Blacks or whites who baited him on college campuses. If he was hurt by their taunts (and he was), he didn’t let it show; he had important work to do, more radical work than we could have known, but he wasn’t going to argue for it in a shouting match. He would not be a creature of the moment.

Ralph Ellison took the long view. The road to liberating this country from a bad past and a worse future meant following the turns and blind alleys that the Black minister Reverend Hickman describes to his young protégé Bliss in the passage quoted at left. Is Bliss white? Is he Black? We can’t know. It was Ellison’s radical view that every real American, even the racebaiting senator that Bliss becomes, is in some sense psychically, culturally Black. Imagine that and you can imagine the daunting mission of this novel to capture the indivisibility of the American experience. He wanted to save us all.

Which brings me to the Jim Crow Museum, the largest collection of racist memorabilia in the country and an institution that had its seminal moment around 1970, when David Pilgrim, who grew up in Prichard and Mobile, Alabama, under Jim Crow, bought a crude piece of racist memorabilia—probably a mammy saltshaker, as he recalls—and then smashed it before going on to amass thousands of racial caricatures in virtually every medium imaginable.

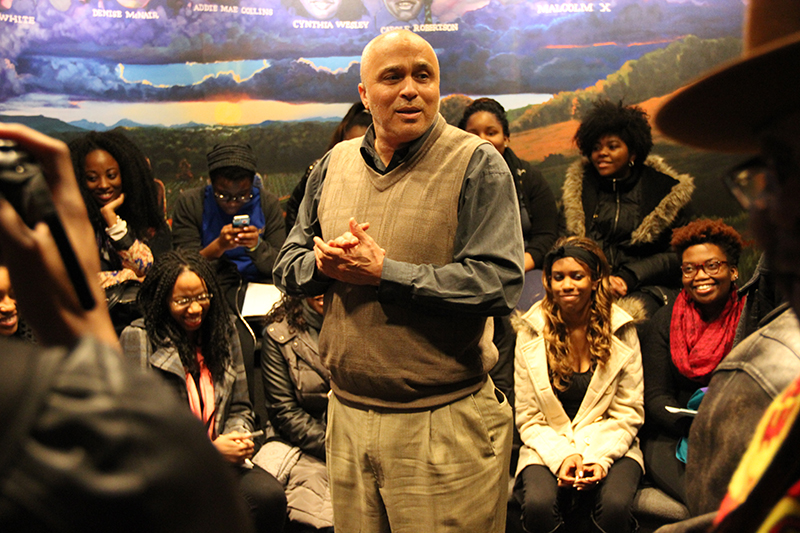

Pilgrim is a professor of sociology at Ferris State, a university of some twelve thousand students of whom roughly one-fifth are people of color. In 2012 the university opened a museum in a converted library to house more than ten thousand of the objects Pilgrim had gathered. Today the Jim Crow Museum welcomes all of us—cops and activists, students and retirees, skinheads and politicians, black, white, and brown— to learn the lesson of tolerance from the objects of intolerance. That is how the museum describes itself, though to my mind it is equally remarkable as a place and a project that will follow Ellison’s “crooks and turns and blind alleys” to arrive at the indivisibility of the American experience. But we will get to that.

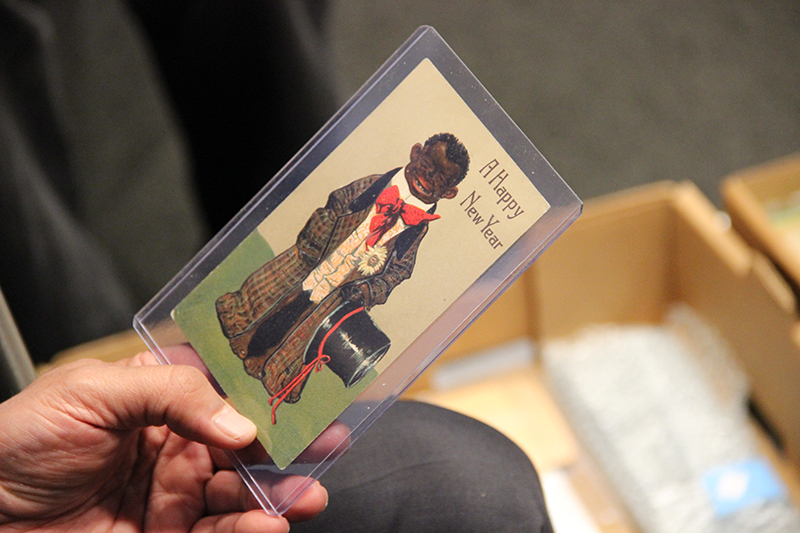

The museum’s mission, like its holdings, is emphatically not confined to the Jim Crow era that ostensibly ended in 1964 with the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Jim Crow lives: the all-too-familiar Toms, mammies, Sambos, and pickaninnies originally created to defame and define Blacks after Reconstruction and thwart their rise to citizenship are still being made, and they have their up-to-the-minute progeny too. Racist items caricaturing Barack Obama as a monkey, Obama with his head in a noose, Obama eating watermelon, and so forth are so numerous, Pilgrim tells me, they could fill a museum of their own. Then, too, the time lag between a high-profile racist event like the shooting of Trayvon Martin and the outpouring of merchandise like Trayvon Martin shooting targets is a short one (they sold out too quickly for the museum to obtain one). But it is not these products from the battered fringe of the American mind sold in online sites like Tightrope.com (nooses a specialty) that tell us what we need to know about the indivisibility of the American experience. It’s the ordinary stuff, the homey stuff still in the marketplace and in antiques shows, and still being manufactured—the Jolly Nigger banks, the mammies, Sambos, and Toms—that join the degraded inextricably to the degraders, whether the latter are sellers, buyers, or simply “innocent” bystanders many of whom may have fond memories of granny’s mammy cookie jar, as well as those who want to insist “it’s just a part of history.” This is the really powerful stuff, and these are the objects, people, and conversations Pilgrim likes to engage, exposing the stale phrase of political correctness for what it is, a latter-day rebranding of what was once simply racial sensitivity.

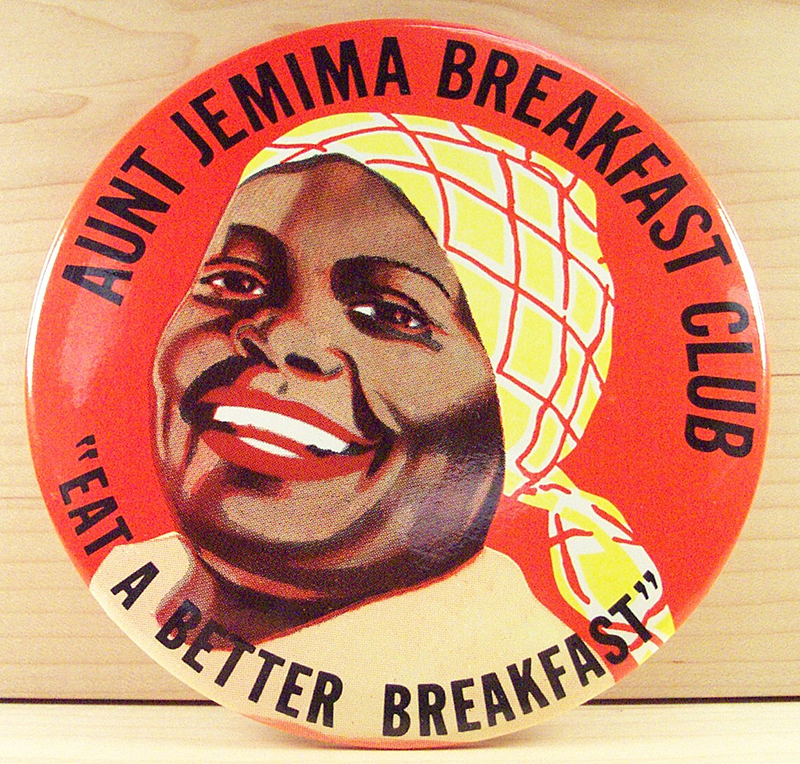

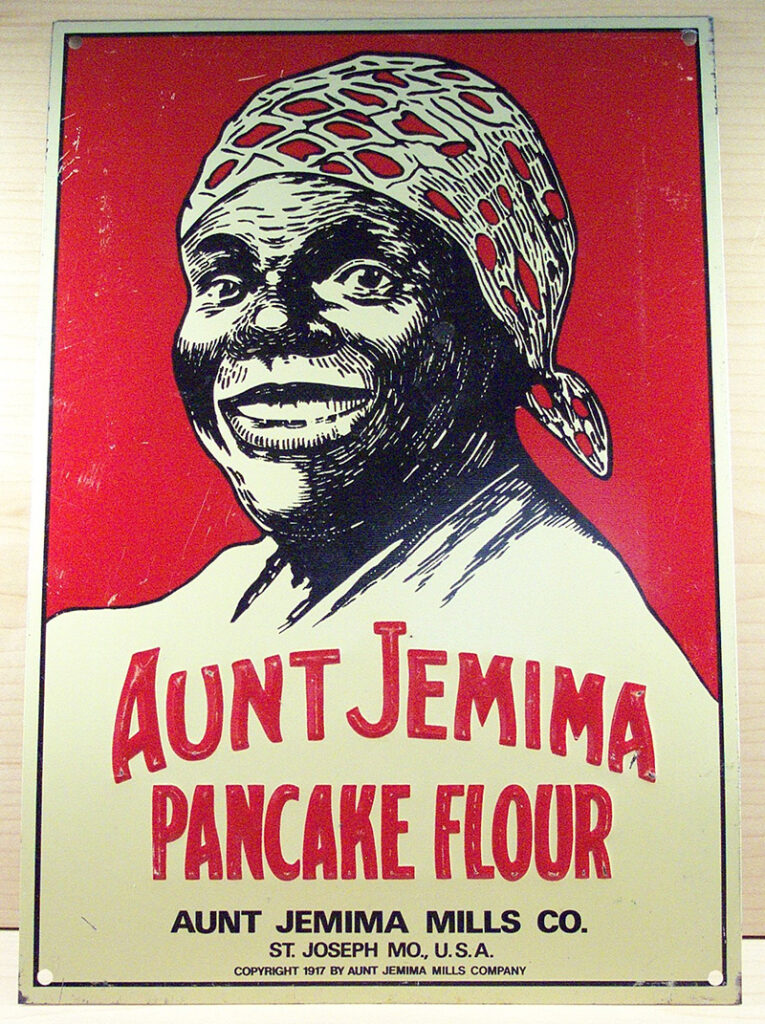

Here is the museum’s approach: Don’t preach. Listen. Make it safe to talk and to listen. Above all, go deep, because even seemingly benign figures like Aunt Jemima and Uncle Ben go deeper still. Before you dismiss the recent disappearance of these two familiar figures as little more than duty twitching to satisfy the current moment, read Pilgrim’s analysis of the mammy figure and others in his two excellent books: Understanding Jim Crow: Using Racist Memorabilia to Teach Tolerance and Promote Social Justice and Watermelons, Nooses, and Straight Razors: Stories from the Jim Crow Museum (both from PM Press).

However explicit its thousands of objects, racism and victimhood do not define Black America, and the Jim Crow Museum is not a prisoner of stereotypes and caricatures. The hallway leading to the exhibition space is lined with photographs of Black people going about their daily lives, a salutary reminder of surviving and thriving; there are also exhibits showing Blacks who fought their stereotypes just as there is space for great achievers, from scientists to soldiers. Even those who participated in their own stereotypes in films and on sitcoms like Sanford and Son and Good Times are here, as they should be.

1960s pin.

1980s display tin with image reproduced from an early 1900s pancake box.

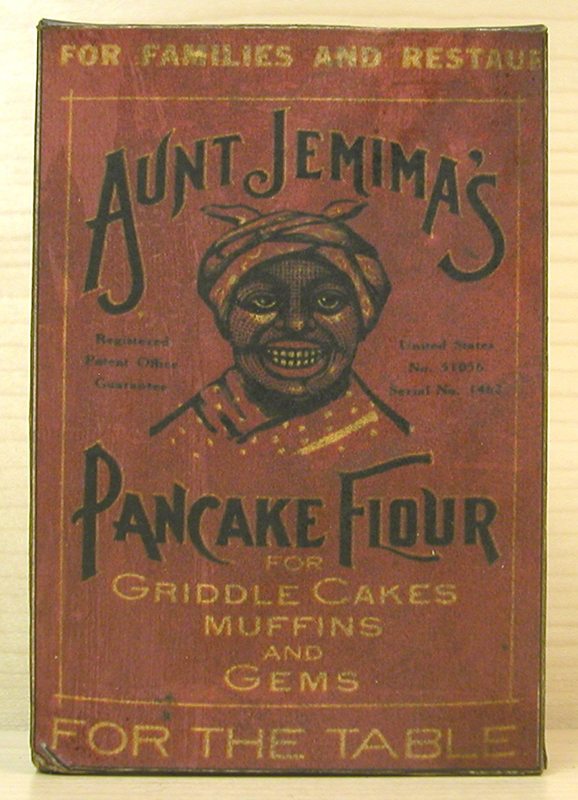

1980s reproduction of early 1900s pancake box.

This is a museum that sees itself as a part of living history and to that end has embarked on a five-year fundraising campaign to build a stand-alone twostory Jim Crow Museum that will be the first thing you see on entering the Ferris State campus. There will be advanced technology, of course, including virtual reality, a history of Jim Crow in Michigan, huge enlargements of Bruce Davidson’s photographs of the Civil Rights Movement, as well as objects that tell the stories of people and organizations who tried to create a more just society—from the Radical Republicans in the nineteenth century down to the present day. With the additional space Pilgrim also hopes to welcome some of the Confederate and other monuments recently removed so that conversations on art, representation, and bigotry can be engaged instead of broken off, so to speak.

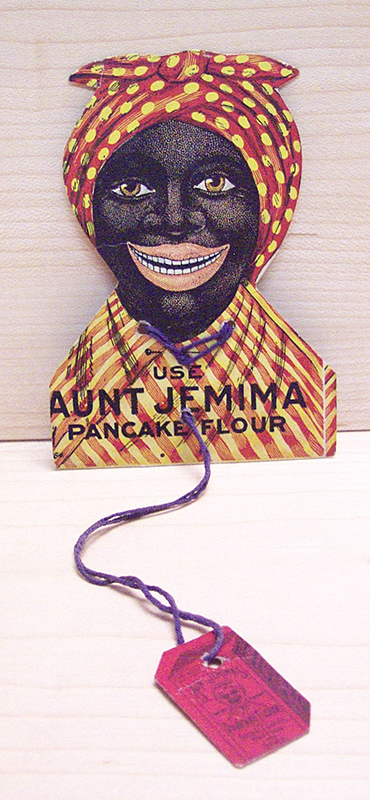

Die-cut cardboard puzzle game from the early 1900s.

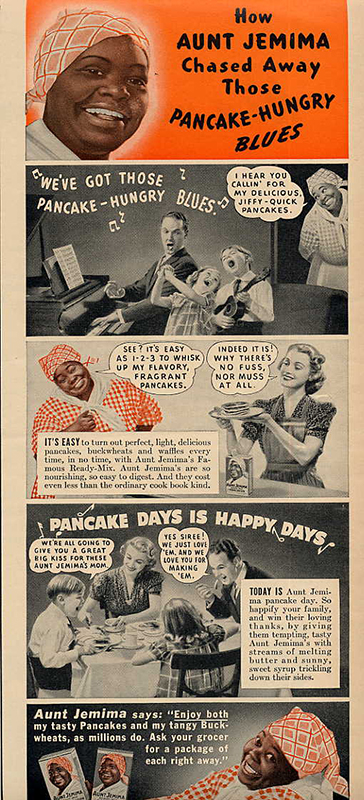

1940s advertisement.

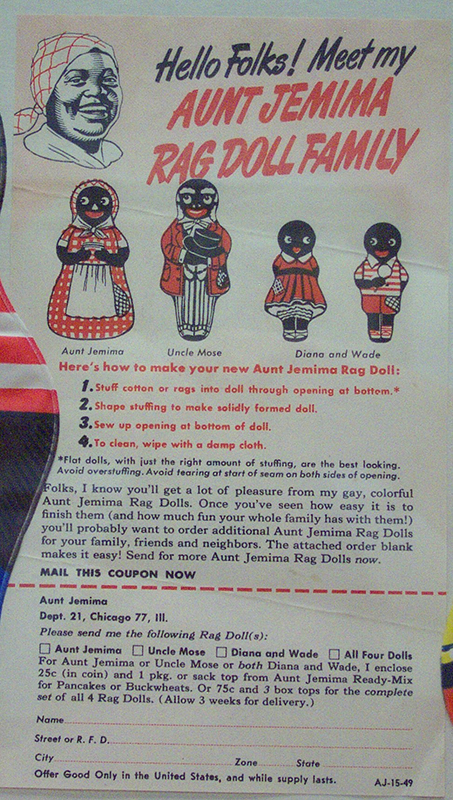

1940s Aunt Jemima Rag Doll Family loyalty program advertisement

There will be a great deal more to keep us traveling the tangled road of who we are and where we are. “White bigots do not have a monopoly on ignorance,” Pilgrim says, and the museum will underline that observation with objects illustrating LGBTQ intolerance, homophobia, and the demonizing of poor whites. They already have a touring exhibition, THEM, with the postcards, games, bumper stickers, and other items that have routinely stereotyped these and other groups of people. But what about sexism? “Ah,” Pilgrim tells me, “I’ve collected so much material on that, it needs its own museum.”

We are in a hot moment just now. “Anger is expensive fuel,” Pilgrim says, knowing that you can’t live on it without eventually summoning the indifference, exhaustion, and invisibility that are so much more dangerous than any backlash. There will be no burnout at the Jim Crow Museum, but there will be and should be more complex conversations ahead with activists and artists, politicians and police. The museum is designed to outlast the moment, pointing the way to the goal of diversity within unity, something Ralph Ellison might have said. In fact, I think he did.