There is no way to know exactly what dance was like in antiquity. There are accounts of it in writings by ancient authors, such as Lucian (c. 120–192), a satirist of imperial Rome. By Lucian’s account, and others, dance was serious business, as central to religious ritual as it was to theater—hardly mere entertainment. Art and artifacts from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome provide a clearer picture of what dance looked like, and those works had a profound influence on modern dance in the early twentieth century. In the nascent days of modernism, the tradition of dance was reexamined, reimagined, and ultimately revitalized. The development was particularly evident in the groundbreaking productions of the Ballets Russes, the Paris-based troupe led by Sergei Diaghilev that revolutionized dance over the course of twenty years, from 1909, until Diaghilev’s untimely death in Venice in 1929, at age fifty-seven.

This surprising and little-explored historical pas de deux of antiquity and modern dance is the subject of Hymn to Apollo: The Ancient World and the Ballets Russes, a remarkable exhibition on view at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World (ISAW). Co-organized by ISAW’s Clare Fitzgerald, associate director of exhibitions and gallery curator, and curatorial assistant Rachel Herschman, in consultation with Ballets Russes scholar Lynn Garafola, the exhibition contains some one hundred objects, ranging from Vaslav Nijinsky’s dance notations for the score of Claude Debussy’s 1912 ballet L’Après-midi d’un faune, and Adolf de Meyer’s famous photographs of that scandalous production, to a first-century BC terracotta relief showing a satyr and maenad ecstatically dancing.

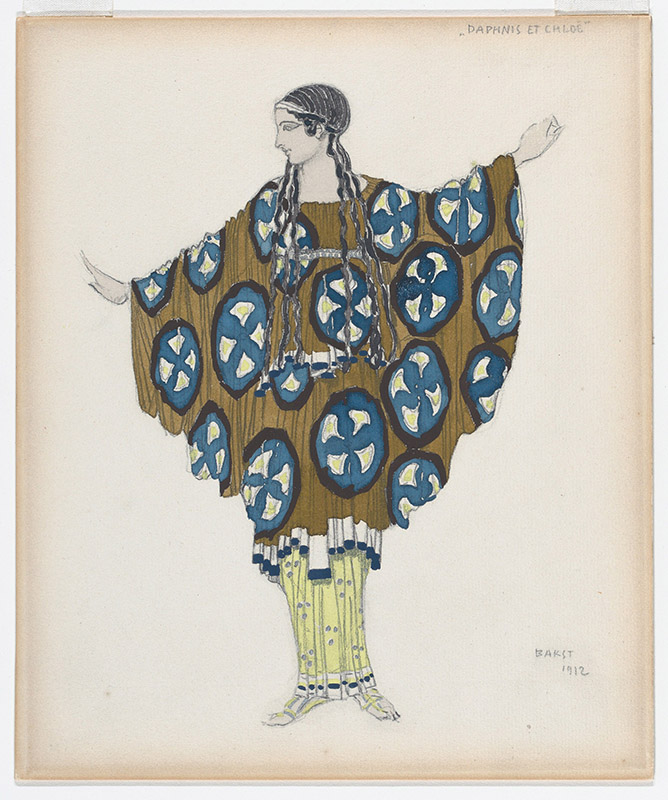

Among the show’s other highlights are studies for sets and costumes by pioneering artists such as Robert and Sonia Delaunay and Giorgio de Chirico. Displayed nearby, ancient works—painted reliefs, vases, and sculptures—bear attributes that directly correspond to these artists’ modernist visions. Of particular interest are the studies for sets and costumes that artist and designer Léon Bakst created for various Ballets Russes’s productions, including Cléopâtre (1913). Adorned with various Egyptian motifs, Bakst’s brilliantly colored costume for one of Cleopatra’s female slaves makes a rare US appearance here. Loaned by the Dansmuseet—Museum Rolf de Maré in Stockholm, the dress miraculously survived a fire that destroyed the sets and nearly all of the costumes for that legendary production.

Hymn to Apollo: The Ancient World and the Ballets Russes • Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, New York • to June 2 •

isaw.nyu.edu