“If it gets to be too much, get rid of it.” When Richard Barker, a former owner of Teviotdale, passed away in 1988, these were among his final words to Victor Cornelius, the present owner. Teviotdale has fascinating historic roots, but there have been numerous practical challenges to maintaining the house over the years. When I photographed it, Cornelius exclaimed “If you’re going to give a house or any physical thing a personality, this one certainly has one!”

Teviotdale was built by Walter Livingston in 1774, a year after his father, Robert Livingston, the third (and last) lord of Livingston Manor, sold him the land for 300 pounds sterling. The property sits between two tributaries of the Hudson River—the Roeliff Jansen Kill and the Klein Kill—in the hamlet of Linlithgo. The house, constructed in the Province of New York while still under English jurisdiction, is distinctly Irish Georgian in its design, with an attention to detail linked to Great Britain’s infatuation with the architecture of Andrea Palladio at the time.

Walter married Cornelia Schuyler in 1767, and the couple lived for several years at the Livingston estate house at the foot of the Roeliff Jansen. During the construction of Teviotdale, he served on the Committee of One Hundred in 1775, formed with the goal of boycotting British goods. He was the first speaker of the New York Assembly, from 1777 to 1779, and a member of the Continental Congress in 1784. His business interests included a sugar plantation in Jamaica and vessels that traded with India and Europe. In 1794 he ran into financial difficulties while attempting to start a new bank and lost his home, which his brothers bought back at auction and resold to him for one dollar.

At Teviotdale, Walter and Cornelia raised eleven children, including Harriet, who married Robert Fulton, designer of the first commercially successful steamship. In 1808 Harriet and Robert were married in front of the fireplace in the Teviotdale drawing room. A 1790 census lists twenty-eight people living in the house on the occasion of a visit for tea from George and Martha Washington. Martha spent the night in the yellow bedroom (Fig. 8).

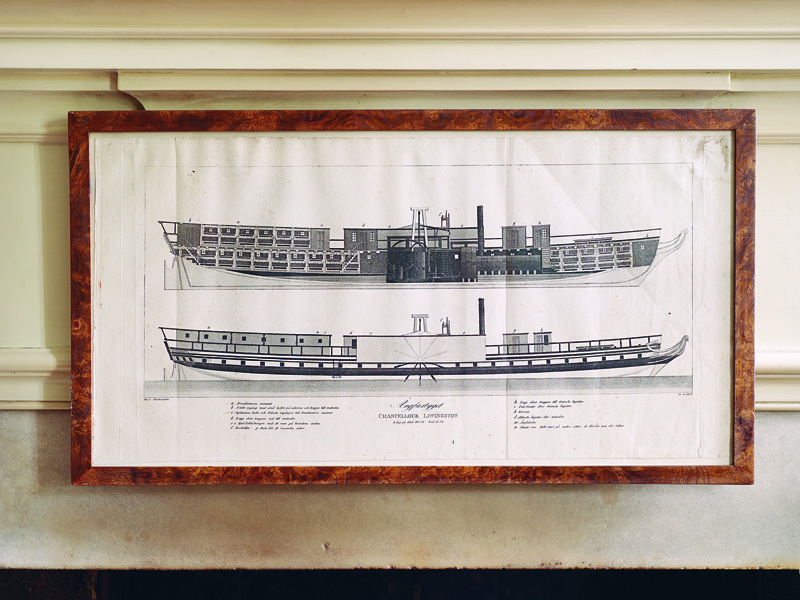

Robert Fulton collaborated with Robert “The Chancellor” Livingston of Clermont on the North River, the steamboat that set sail on August 17, 1807, from a dock on Cortlandt Street in Manhattan heading to Albany. The two men had met in Paris, where Livingston had been sent as US minister to France in 1801. Their point of introduction was punctuated by their mutual obsession with steam power, particularly when used to propel ships.

Livingston, a gentleman of the Enlightenment, had previously experimented with designs approximating a steamship but with no great success. In 1802 he and Fulton entered into a partnership agreement for a steamboat whereby Livingston would supply the financing and the monopoly for access to the Hudson River and Fulton would be in charge of the design. Both were to share in the eventual profits of the enterprise.

At the mid-point of its inaugural voyage up the Hudson, the North River docked at Clermont, the ancestral Livingston estate across the river from the Catskill Mountains. (The steamboat was later renamed and became known as the Clermont.) An often-contested Livingston family legend claims that the Chancellor used the occasion to announce the engagement of Walter’s daughter Harriet to Fulton.

The newlyweds spent time at Teviotdale with Cornelia Livingston. (Walter Livingston had died in 1797.) Robert filled his days painting, returning to the talent that had occupied him before becoming famous and wealthy from the steamship.

When Robert Fulton died in 1815 at age fifty, having contracted pneumonia after rescuing his attorney from the Hudson River, Harriet was left with four children. She purchased Teviotdale from her brother John, who had inherited it from their father with an accompanying 168 acres. Shortly thereafter, she married Charles Dale, a cultured Englishman, and began yet another round of home improvements including the addition of a central Palladian window, and elongating the back and side windows in the French fashion.

When the Fulton fortune was depleted, Dale tired of America and took Harriet back with him to England. Eventually in need of funds, Harriet and Charles Dale mortgaged Teviotdale for ten thousand dollars in 1820, six years before Harriet died, continuing the complicated financial maneuvers associated with the history of the house. In 1833 the Bank of England foreclosed on the unpaid mortgage and the property was sold to another member of the family, Carroll Livingston, who was involved with several speculative land transactions at the time. He immediately sold Teviotdale on a diminished acreage to Christian Cooper, who had worked at Moncrief Livingston’s nearby gristmills as its first miller and as a footman at Teviotdale. He lived to be 110 years old and eventually divided the property among his three children.

John Ross Delafield, the owner of Montgomery Place in Red Hook, purchased Teviotdale, now on a plot of land that had been whittled down to four acres, from Cooper’s grandson Frank in 1927. This was intended as a gift for John’s second son, Richard, whose widow, Margaret, returned it to her father-in-law when her husband died in 1945. John left Teviotdale boarded up and dormant. He set up the Delafield Mansion Corporation, which included in its holdings Montgomery Place and Teviotdale.

The sleeping beauty was forgotten until 1969 when Harrison Cultra and Richard Barker were shown the property while staying at Grasmere as guests of Louise Timpson, the former Duchess of Argyll. Cultra later told Victor Cornelius that “the trees and foliage were growing so close to the facade that we couldn’t even open the shutters.” Fifteen thousand dollars bought them a project few would dare to attempt. The house was open to the elements and had never had any plumbing or electricity.

Cultra and Barker met in Paris in 1958 while Cultra was studying at L’École des Beaux-Arts and Barker was head of advertising at the International Herald Tribune. After ten years in Paris, the two returned to New York City following the 1968 student uprisings. Cultra began working with decorator Rose Cummings and then formed a partnership with Georgina Fairholme, which lasted until 1974. He went on to develop a highly successful office of his own, with clients who included Jacqueline Onassis and local Hudson valley friends Richard Jenrette and Sam Hall and his wife, Grayson. Barker went to work at the advertising agency Doyle Dane Bernbach.

After a significant amount of structural stabilization, Cultra, assisted by Fairholme, began the interior decoration of the house. Walter Livingston’s order books are intact and reside at the New-York Historical Society. Consequently much information regarding the original materials was available while the twentieth-century restoration was in progress.

No records of the finishes or details of the decoration survived, except for several bits of remaining wallpaper, leaving Cultra on his own. He reported in Architectural Digest that he took “what I considered to be a sensible but imaginative approach. I decided to treat the house as though the long hiatus between its two flowerings had never existed—that one family had been in residence the entire time. I decided that the Livingstons would have been Francophiles, which explains the French Empire furniture. The Fulton era is reflected in the library where I keep a collection of memorabilia associated with the inventor’s life.”1 This includes an 1827 drawing of the house by Fulton’s daughter, which illustrates unrealized plans for two symmetrical hyphens, connecting elements leading to octagons on either side of the main block. “I did take liberties, but I felt, in a very real way, that I was entitled to. If you subscribe to my theory of continuity, it was my ‘contribution’ to the story of the house.”2 One of the “liberties” was the construction of the Chinese Chippendale staircase, whose inspiration is at Bohemia Manor, in Cecil County, Maryland (Fig. 5).

Victor Cornelius first arrived at Teviotdale as a guest of Cultra and Barker in 1979, when the interior decoration had all but been completed, and became close to the two. Cultra died in 1983; Barker passed away in 1988, and willed the house to Cornelius. Stored away there are the videos Cornelius produced in the 1980s documenting oral histories of the occupants of many homes along the Hudson at the time, including Margaret Suckley at Wilderstein, Honoria Livingston McVitty in Sylvan Cottage at Clermont, and Deborah Dows at Southlands. According to Cornelius, “The people I was meeting up here were of a particular sort . . . struggling to stay on their family properties. I went from being the person recording the process to being a part of the process.”

Thirty years after Barker’s death, there is an invigorated energy in Teviotdale’s preservation so that the property, which had dwindled down to four acres, is now inching back in the direction of the original 541. Today, working on a series of land acquisitions and a family trust, Cornelius is adding his own expertise to correct the property’s precarious history. The goal is to maintain Teviotdale as a private house. Says Cornelius: “Sure, it could be a museum. It is one of the most historic houses in America that is still in private hands. But am I going to turn it over to the State or make it a not-for-profit? No, sir. And besides, the moment you stop being able to light the fireplaces, the house dies.”

This article is excerpted and adapted from Life Along the Hudson: The Historic Country Estates of the Livingston Family, written and photographed by Pieter Estersohn and published by Rizzoli ($85).

1 Peter Johnson, “Teviotdale: Designer’s Eighteenth-Century Home in Upstate New York,” Architectural Digest, vol. 4, no. 6 (June 1983), pp. 126–146; p. 126. 2 Ibid.

Pieter Estersohn is a leading photographer of architecture and interiors whose work regularly appears in shelter magazines. The president of the Friends of Clermont and a board member of the Calvert Vaux Preservation Alliance, Estersohn is presently working on two books: one about new farms of the Hudson Valley; the other on private Manhattan gardens.