The Magazine ANTIQUES | May 2009

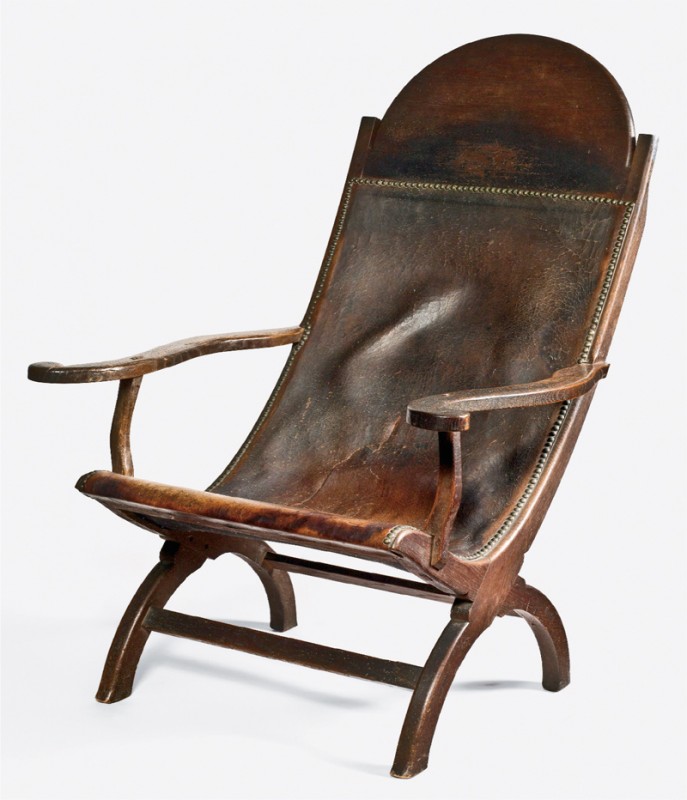

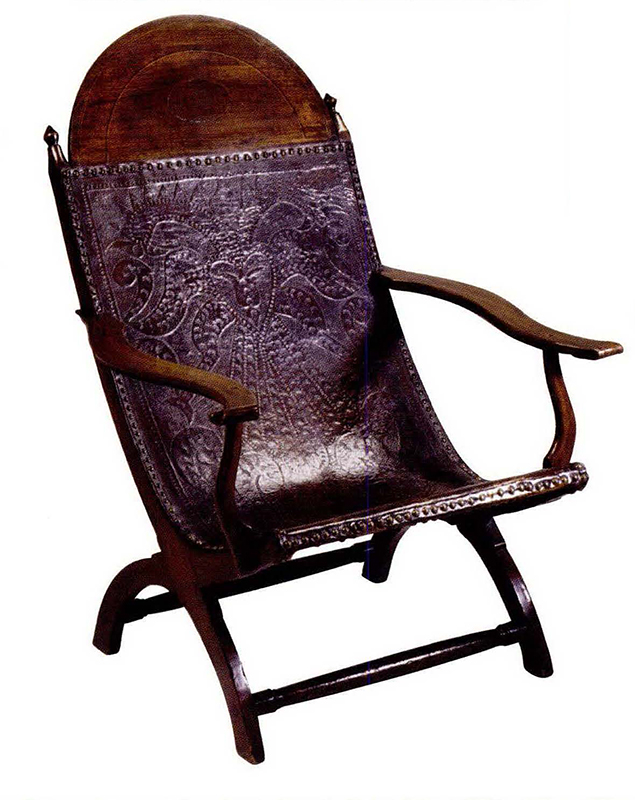

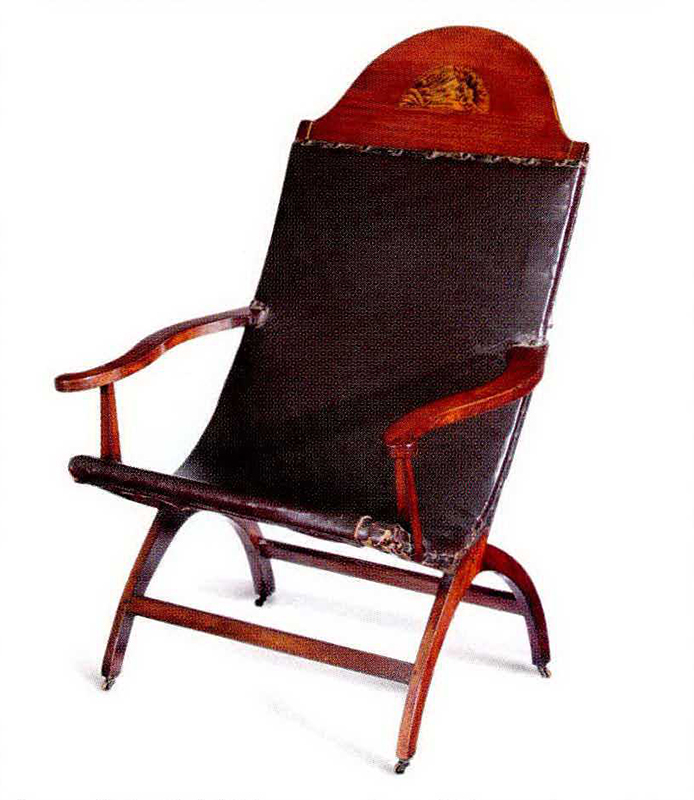

On March 8, 1827, Joseph Coolidge (1798–1879), the husband of Thomas Jefferson’s granddaughter Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge (1796–1876), wrote to Nicholas P. Trist (1800–1874), another of Jefferson’s grandsons-in-law, regarding the distribution of the Monticello, Virginia, estate: “Ellen now desires me to say that if you can procure the Campeachy chair, with [Jefferson’s] initials, she wishes you to do so, at any price.”1 The current location of the chair is unknown, though a mahogany example with a scallop crest that descended in the Trist family to Thomas Jefferson Trist (1828–1890) is now at Monticello. The Jefferson family’s use of Campeches is verified in letters, including one that Virginia Randolph Trist (1801–1882) wrote to her sister Ellen shortly after her wedding to Coolidge: “He [Jefferson] misses you sadly every evening when he takes his seat in one of the campeachy chairs, & he looks so solitary & the empty chair on the opposite side of the door is such a melancholy sight to us all.”2 A graceful emblem of plantation society in the Americas, the Campeche chair is characterized by a lateral non-folding curule base and a reclining back and seat made of embossed leather (see Fig. 1). Nineteenth-century examples in the United States are found principally in the South, especially Louisiana. Such chairs are also prevalent in Latin America, Spain, the Balearic Islands, and in locations that were situated along seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Spanish trade routes, such as Indonesia. Since the publication of Celia Jackson Otto’s article “Nineteenth-century contour chairs” in the February 1965 issue of The Magazine Antiques, considerable evidence has been gathered that enriches our understanding of the use of Campeches in the Americas.

A graceful emblem of plantation society in the Americas, the Campeche chair is characterized by a lateral non-folding curule base and a reclining back and seat made of embossed leather (see Fig. 1). Nineteenth-century examples in the United States are found principally in the South, especially Louisiana. Such chairs are also prevalent in Latin America, Spain, the Balearic Islands, and in locations that were situated along seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Spanish trade routes, such as Indonesia. Since the publication of Celia Jackson Otto’s article “Nineteenth-century contour chairs” in the February 1965 issue of The Magazine Antiques, considerable evidence has been gathered that enriches our understanding of the use of Campeches in the Americas.

An exotic curiosity to its North American owners, the Campeche stands today as a reminder of the trade culture in the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean region and of Hispanic social and cultural influence in the Lower Mississippi River valley. It is named for the Bay of Campeche, in the Gulf of Mexico, and the port city of Campeche on the Yucatán Peninsula, better known for its trade in logwood (Haemytoxylon campechianum).3

In Louisiana, for generations the form has been called a boutaque, French patois for the Spanish word butaca meaning armchair, and the name has also been anglicized as Campeachy. Early nineteenth-century inward foreign cargo manifests in the collection of the National Archives and Records in Fort Worth, Texas, document the shipment of “Spanish chairs,” “boutaque” chairs, and “arm-chairs” from coastal towns of the Yucatán—Campeche, Veracruz, Sisal, and Tabasco—to the port of New Orleans from about 1800 to 1825. The imports sometimes included butaquitos, which are diminutive versions.

As Mexican Campeches were becoming popular in New Orleans, similar neoclassical permutations enjoyed a vogue in Europe. Notable examples include a palisander-veneered curule writing chair (Krankenstuhl) owned by the Prussian monarch Frederick William III (r. 1797–1840), possibly designed by the architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781–1841) in 1829 (Hohenzollern Museum, Schloss Charlottenburg, Berlin).4 A drawing of about 1790 signed “Menuier inv. et fecit” and entitled Projet de chaise à l’antique depicts an armless version upholstered in pale blue embroidered silk with paterae and gold fringe (Fig. 3). A realization of this design (c. 1795) in mahogany has been attributed to Georges Jacob (1739–1814).5 Anne-Marguérite-Henriette Rouillé de Marigny, Baroness Hyde de Neuville completed a small graphite sketch during her passage aboard L’Alerte from Barcelona to the United States that depicts two children sleeping, one in a Spanish chair identifiable by its arched crest, carved finials, and reclining back (Fig. 5).6 The similarity of the overall configuration of the chair in the sketch—particularly its crest and finials—to one now at Elgin Plantation in Natchez, Mississippi (Fig. 8), points to the Campeche’s Spanish origin and later popularity among Mississippi River valley planters.

The Campeche and its European counterparts derive from the sella curulis, or magistrate’s chair, a cross-legged seat used in ancient Rome by the highest dignitaries, who were named curule aediles and magistratus curules.7 As its base the sella curulis, like much Roman architecture, employed the arch, the quintessential symbol of Roman authority. During the late Roman Empire, the addition of an extended back to this seat resulted in a new type of chair with a lateral curule base, examples of which are known from carved ivory depictions.

By the Renaissance, this form was referred to in Spain as silla francesa (or French seat), perhaps in reference to Gallic mendicant orders who brought it there.8 A second type with a front-facing curule base appeared across Europe during the Renaissance and was known in Spain as sillón da cadera (or hip-joint armchair); during the nineteenth-century Renaissance revival, they were called Dante or Savonarola chairs. Both the sillón da cadera and silla francesa were transferred to Nueva España by the Spanish.9

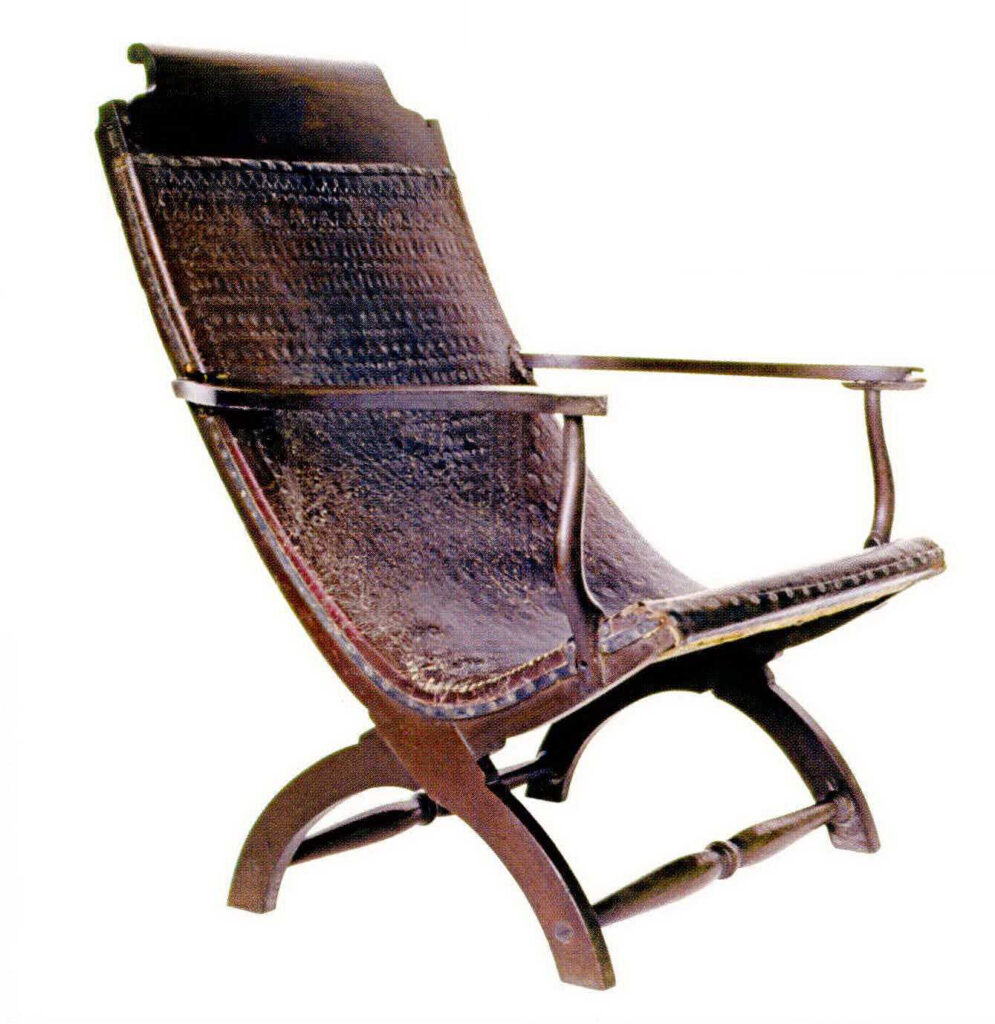

Aztec codices and other eyewitness accounts of the arrival of Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) in Mexico in 1519 show him seated in a sillón da cadera. As the furniture historian Abelardo Carrillo y Gariel explains, “These chairs were merchandise for importation to the America of the 1500s and were brought all the way from the peninsula to these regions by the vessels of the Carrera de las Indias.”10 While the sillón da cadera became obsolete, the lateral curule base chair endured, in part because its reclining back provided comfortable repose in the sultry climes of Latin America. With its arched crest and finials echoing Spanish colonial cathedral facades, the so-called butaca became strongly associated with Mexican, West Indian, and South American culture. Mexican Campechanos brought the form to Havana, where it is also called a Campeche. Today, an important pair of Campeches crafted in Cuba is in the collection of the Museo de Arte Colonial in Old Havana. A similar one that has belonged to a Jeanerette, Louisiana, family since the 1930s may have originally been imported by sugar industry workers, many of whom traveled back and forth from Havana regularly. Like other Cuban examples, including the Museo de Arte Colonial pair, this chair has an elongated shape, wide flat arms, and a denticulated crest rail.

An early depiction of the use of Campeche chairs in the United States is Benjamin Henry Latrobe’s January 1819 watercolor of the view from his room at Tremoulet’s Hotel in New Orleans (see frontispiece). Having designed a number of elegant Greek revival klismos chairs for the Madison White House in 1809,it is not surprising that Latrobe, who moved from Baltimore to New Orleans to complete a commission for a waterworks, would take notice of a local chair with classical origins.

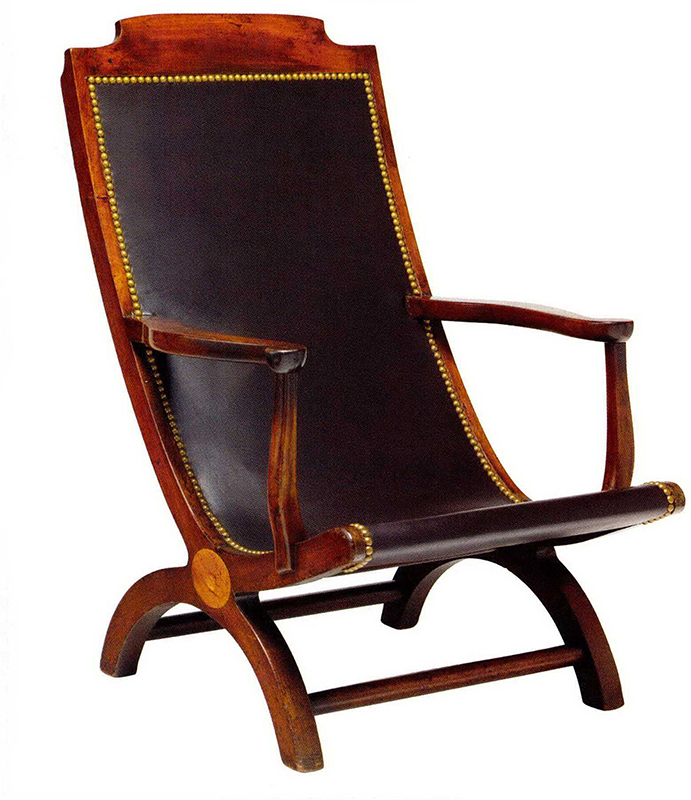

A number of early Campeches now in American collections arrived in New Orleans from Mexico or are early copies of Mexican imports; all of them have elaborate guadamacil (tooled-leather) seats. Perhaps the most important example is the chair in Figure 7, which belonged to James Madison and is believed to have been a gift from Jefferson. It is distinguished by a highly stylized Spanish Habsburg double-headed eagle featured on its seat back. In her 1850s memoir, Mary Cutts (1814–1856), a niece of Dolley Madison (1768–1849) and a frequent guest at Montpelier, Madison’s house in Orange, Virginia, wrote: “Statuary beautifully chiseled occupied the mantel, Mr. Madison’s favorite seat was a campeachy chair.”11 The Orange-Fluvanna group, consisting of five Campeches (in white oak and white ash) in Virginia collections, has a constellation of features similar to the Madison chair and appears to have been inspired by it.12 Two of the five have unusual elongated backs; one was discovered in the Mathews County, Virginia, courthouse in 1975 and the other remains in private hands. The three others, once owned by other Jefferson neighbors and more closely resembling the Madison chair in overall proportions, are at Monticello and in a private collection (see Fig. 2). Monticello conservator Robert L. Self and I hypothesize that the group may represent the handiwork of master joiners James Dinsmore or John Neilson, both of whom worked at Montpelier and nearby estates after finishing their work at Monticello in 1809, and either may have copied Madison’s chair.

Another Campeche possibly imported into New Orleans from Mexico is one of a pair said to have been presented by Jefferson to Louisiana Representative Thomas Butler (1785–1847) between 1818 and 1821 (Fig. 4).13 Although this chair’s mahogany frame could easily be the product of Louisiana workmanship, its guadamacil sling seat was probably made in Mexico or even possibly Spain.

In her biography of the New Orleans merchant James Colles (1788–1883), his granddaughter Emily Johnston De Forest (1851–1942) mentioned his favorite belongings, including a “comfortable Spanish chair, which he so loved and which probably had been brought from Mexico and purchased by him in New Orleans.”14 Shown in Figure 11, the chair has a leather seat with a design that is remarkably similar to that of Butler’s chair in Figure 4. In the same period that Colles obtained his Campeche, the planter James Jackson (1782–1840), the builder of the Forks of Cypress, a peripteral manse in Florence, Alabama, purchased a nearly identical one for his wife Sarah during a trip to sell cotton in New Orleans. A third version, now in the Holden family collection in Point Coupée, Louisiana, is probably one of nine copies of their grandfather’s chair the Colles family commissioned in the 1880s from the New York cabinetmaker Ernest F. Hagen (1830–1913).15

Louisiana furniture makers probably began copying the Mexican chairs soon after they first arrived at the New Orleans levee. Two Louisiana-made examples bear leather seats with embossed eagles. The leather on the chair in the Hollensworth collection at the Jacques Dupré House in Point Coupée is embossed with two distinct motifs: a delicately etched (now quite faded) oval cartouche with an American eagle, all within a blossoming-vine border, on the seat back; and, on the lower section, a roundel within a square with a quarter fan at each corner. This geometric pattern is frequently seen on Mexican furniture. The design on the leather of the chair in Figure 1 is nearly identical, suggesting both upholstery leathers came from the same workshop.

There are numerous examples of other regional interpretations of Campeches in the United States. At present, there are seven such American-made chairs at Monticello, two of which have direct links to the Jefferson family. The term “Campeachy” first comes up in Jefferson’s correspondence in a letter of August 8, 1808, to William Brown, collector of customs for the district of Mississippi in New Orleans, in which Jefferson writes, “Mrs. Trist, who is now here and in good health informs me that the Campeachy hammock, made from some vegetable substance netted is commonly to be had at New Orleans.”16 Although hammocks are different from chairs and are listed separately from chairs in a number of manifests I have examined, it is conceivable that Elizabeth Trist (c. 1751–1828), who spent time in New Orleans with her son, Hore Browse Trist Sr. (1775–1804), whom Jefferson made collector of customs at Natchez and New Orleans in 1802 (and whose son Philip married Jefferson’s granddaughter Virginia) informed Jefferson about Campeche chairs as well.

Campeche chairs are mentioned in a letter Jefferson received on August 2, 1819, from Thomas B. Robertson, a Virginian who had served as secretary of the Territory of New Orleans (1807) and as Louisiana’s first representative in the House (1813):

I transmit to you a small volume of letters, written to my father from Paris…I hope you will give it the advantage of an agreeable attitude while seated in your Campeachy chair. Many years ago you asked me to send you a few of these chairs; embargo, war, the infrequency of communication between N.O. and the ports of Virginia and my being in Congress prevented me from complying with your request. Meeting with two some weeks ago on the levee and hearing that there was a vessel then up for Richmond I had them put on board; one I sent to my father and the other to you.…if you wish for more, I can now at any time procure & forward them to you.17

Having not yet received the chair, on August 24, 1819, Jefferson wrote to his daughter Martha Jefferson Randolph (1772–1836) explaining that he wished for a Campeche to be brought to Poplar Forest, his plantation in Bedford, Virginia, to ease his rheumatic discomfort: “I longed for a Siesta chair…the one made by Johnny Hemings…if it is the one Mrs. Trist would chuse it will be so far on its way.”18 It is not known which, if any, of the chairs now at Monticello is the “Siesta chair” made by John Hemmings (1776–1833). The aforementioned Orange-Fluvanna group cannot yet be entirely discounted as his work, but it appears far less likely based on recent reexamination of nineteenth-century documents by Monticello researchers.

Finally, on January 27, 1821, Jefferson wrote to Joel Yancey (1774–1833), the overseer at Poplar Forest: “There is an arm-chair at Poplar Forest which was carried up in the summer, and belongs to Mrs. Trist. It is crosslegged [and] covered with red Marocco, and may be distinguished from the one of the same kind sent up last by wagon as being of brighter, fresher colour, and having a green ferret across the back, covering a seam in the leather.”19

That Jefferson loved and promoted the Campeche chair is generally understood, and he is credited with popularizing the form in Washington. An example of about 1815–1820 found in Woodville, Mississippi, in the 1980s was recently identified by Sumpter Priddy III as the work of the Washington cabinetmaker William Worthington Jr. (Figs. 12–12b). Henry V. Hill, a cabinetmaker on Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, is recorded to have offered “Spanish chairs introduced here by Mr. Jefferson” in 1825.20 Other examples made in Charleston (see Fig. 13) and Philadelphia speak to their wider use in the United States.

Beginning in the 1830s Campeches were included in English and American price books such as The Philadelphia Cabinet and Chair Maker’s Union Book of Prices for Manufacturing Cabinet Ware (1828), the Third Supplement to the London Chair-Makers’ Book of Prices for Workmanship (1844), and William Smee and Sons’ Designs of Furniture (London, [c. 1850]). A Campeche chair owned by Franklin Bache (1792–1864), Benjamin Franklin’s great-grandson, was perhaps ordered from the Philadelphia price book (Fig. 9). The American artist Worthington Whittredge painted his father-in-law, Judge Samuel A. Foot(e) (1790–1878), seated in one of a pair of Campeches on the porch of his house in Geneva, New York (Fig. 6).21 A canvas by George Bacon Wood showing the library in the Philadelphia residence of the economist and art collector Henry C. Carey shows several curule type forms including a rocking chair (Fig. 10).

In the twentieth century, designers began to look at these chairs anew. The architect and writer William Spratling (1900–1967), known as the “Father of Mexican Silver,” produced butaquitos at his firm Spratling y Artesanos, which he founded in Taxco, about two hundred miles north of Acapulco, in 1931. During the 1940s, the Cuban-born designer Clara Porset (1895–1981) accepted an invitation to participate in the Organic Design in Home Furnishings contest held by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.22 One of her most noted furniture designs, the “evolved butaqaue,” inspired by a fifth- or sixth-century Totonac sculpture of a figure on a majestic throne, attracted the attention of the Mexican architect Luis Barragán (1902–1988), who commissioned Porset to design furniture for his houses Casa Prieto López (built 1943–1949) in Mexico City, and Casa Antonio Gálvez in San Angel, Mexico (built 1954).

The sleek MR 90 Barcelona chair Ludwig Mies van der Rohe (1886–1969) designed for the German pavilion at the 1929–1930 Exposición Internacional de Barcelona was an homage to Alfonso XIII (r. 1886–1931) of Spain, calling to mind a long history of association of the X-frame with political power. Indeed, it was almost inevitable that when the Campeche form first reached American shores in the early nineteenth century, statesmen such as Jefferson and Madison would find its classical aspect fascinating. For these leaders, who were deliberately emulating the ancient prototype of Cincinnatus—the farmer called into the service of his nation as a soldier and ruler and then returning to his fields, resisting at all times the temptations of here-d-itary monarchy—the Campeche gave rest not just to their bodies, but to their democratic souls.

The author acknowledges the following for their invaluable assistance: Nancy Britton, Barry R. Harwood, the Historic New Orleans Collection, Peter M. Kenny, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Anne-Emmanuelle Piton, and Sumpter Priddy III. A travel grant from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2004 made possible research and lectures in Campeche and Mexico City.

1 Ellen W. R. Coolidge to Nicholas P. Trist, March 8, 1827, Papers of Nicholas Philip Trist, Library of Congress, Washington, reproduced on Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series Digital Library. It is possible that Coolidge confused the Campeche with the French chair now in the dining room at Monticello. Trist had carved the initials “TJ” into the chair’s left arm. 2 Virginia R. Trist to Coolidge, June 27, 1825, Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge Correspondence, University of Virginia Library, Charlottesville, reproduced ibid. 3 Logwood (or bloodwood) is used to make Hematoxylin, a scientific stain used in microscopy. It is difficult to work and not usually used for the construction of furniture, as is often believed. 4 I thank Ulrike Eichner and Ute Roenneke for examining this chair with me in conservation at the Neue Palais, Potsdam. 5 See Galeries nationals du Grand Palais, Paris, and Altes Museum, Berlin, Les Etrusques et l’Europe (Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris, 1992), p. 393; and Jean-Marie Bruson and Anne Forray-Carlier, Au temps des merveilleuses: la société parisienne sous le Directoire et le Consulat (Musée Carnavalet, Paris, 2005), p. 182, no. 281. 6 Jadviga M. Da Costa Nunes, Baroness Hyde de Neuville: Sketches of America, 1807–1822 (Jane Voorhes Zimmerli Art Museum, Brunswick, N.J., and New-York Historical Society, New York, 1984), pp. 2–3. 7 For a complete account of the form’s history, see Ole Wanscher, Sella Curulis, the Folding Stool: An Ancient Symbol of Dignity (Rosenkilde and Bagger, Copenhagen, 1980). 8 Juan José Junquera y Mato, “Mobiliario,” in Artes decorativas II, vol. 45 of Summa Artis: Historia general del arte, ed. Alberto Bartolomé Arraiza (Espasa Calpe, Madrid, 1999), p. 399, tentatively identifies the silla francesa with the chaise perroquet of France. Sillón comes from the Latin word sella meaning seat. Cadera derives from the Latin cathedra meaning the chair or seat of a bishop (hence ex cathedra, meaning “from the chair”) and came to denote the hip. 9 For an expanded discussion, see Cybèle Trione Gontar, “The Campeche Chair in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,” Metropolitan Museum Journal, vol. 38 (2003), pp. 183–212. 10 Abelardo Carrillo y Gariel, Evolución del mueble en Mexico (Instituto Nacional de Antropologîa e Historia, Mexico, 1957), p. 10. 11 “Memoir about James and Dolley Madison,” Mary Estelle Elizabeth Cutts Papers, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts. 12 See Robert L. Self and Susan R. Stein, “The Collaboration of Thomas Jefferson and John Hemings: Furniture Attributed to the Monticello Joinery,” Winterthur Portfolio, vol. 33, no. 4 (Winter 1998), pp. 241–242. Subsequent research at Monticello has called into question the attribution of these chairs to the Monticello joinery. 13 Butler, who was appointed judge of the Louisiana Third District Court in 1813, was elected to finish the term of Congressman Thomas B. Robertson (1773–1828). 14 Emily Johnston De Forest, James Colles, 1788–1883, Life and Letters (privately printed, New York, 1926), p. 212. 15 Emily Johnston De Forest, “The House, 7 Washington Square, and an Inventory of Its Contents,” April 1928, Hagen furniture file, Department of Drawings and Prints, Metropolitan Museum of Art. 16 Jefferson to William Brown, August 8, 1808, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston. 17 Thomas B. Robertson to Thomas Jefferson, August 2, 1819, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. 18 Jefferson to Martha J. Randolph, August 24, 1819, Jefferson Papers, University of Virginia, reproduced on Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series Digital Library.

19 Jefferson to Joel Yancey, January 27, 1821, reproduced on Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Retirement Series Digital Library. Campeche chairs were traditionally covered in red leather. 20 Anne Castrodale Golovin, “Cabinetmakers and chairmakers of Washington, D.C., 1791–1840,” The Magazine Antiques, vol. 107, no. 5 (May 1975), pp. 914–915. 21 I thank Matthew A. Thurlow for pointing out this painting to me, and Anthony Janson and Karen Osburn for providing additional information. The Van Brunt-Foote House still stands at 46 DeLancey Drive in Geneva. 22 See Mary Roche, “Furniture Depicts Different Mexico: Room Setting Now on View Reflects Country’s Trend Away from Clutter,” New York Times, February 4, 1947.

CYBÈLE T. GONTAR is a co-author of The Furniture of Louisiana, Colonial and Federal Periods, Creole and Vernacular, 1735–1835 (forthcoming spring 2010) and an adjunct professor of art history at Montclair State University in New Jersey.