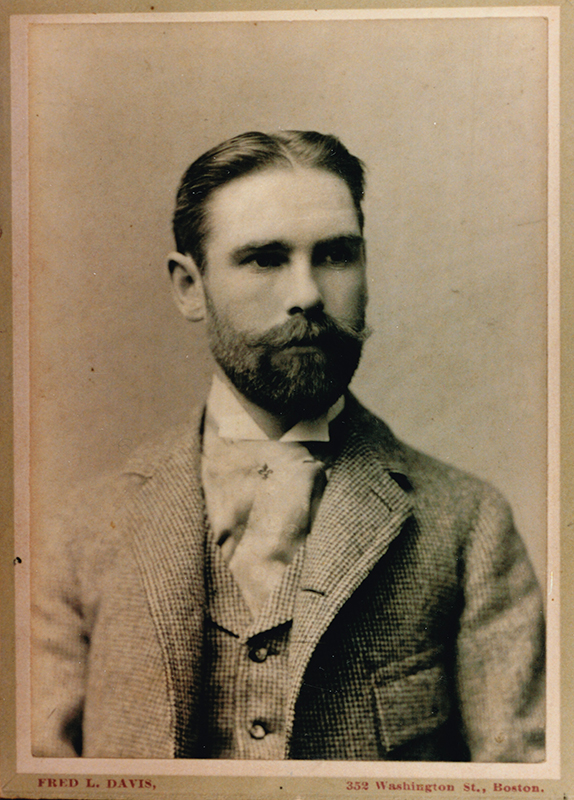

After John Leslie Breck’s premature death in 1899, his obituaries stated that an exhibition of his paintings was to have opened a day later at a Boston gallery.1 In the absence of any other indications of an impending exhibition, good reasons exist to doubt that a show was actually planned: as Breck appeared to have taken his own life, his friends and family were at pains to dispel rumors of suicide by implying that he was looking forward to a bright future. Recent research suggests, however, that if an exhibition had taken place, it would almost certainly have focused on views of Venice, which Breck had visited in 1897, likely with just such an exhibition in mind. During his final years, Breck created a large number of Venetian views, none of which were shown publicly during the nearly two years between his return from Venice and his death. The two memorial exhibitions held after his passing, however, the first at the St. Botolph Club in Boston and the second at the National Arts Club in New York, offered the public a glimpse of an exhibition focusing on the Venetian works that never occurred.

Minor inaccuracies in the biographical essay included in the memorial show catalogues have led to the mistaken impression that Breck arrived in Venice in 1896. In fact, he invited his closest male friends to a “gander party” at his Auburndale, Massachusetts, home/studio on November 6, 1896,2 and a little over one week later he checked into the Grand Union Hotel in Manhattan, presumably prior to departing for Europe.3 By February 1, 1897, Breck and his mother, who throughout his life joined him on most of his travels, had arrived in Berlin, where Breck’s brother Edward had been working for the US government since 1895.4 There they attended a fencing match at the Berlin Fecht-Club, where Edward, a champion fencer (among many other remarkable accomplishments), competed.5 During John’s stay in Berlin, Edward probably used his many local connections to arrange the exhibition of his brother’s paintings held at Gurlitt’s art galleries in Berlin in late March or early April.6 No doubt, John waited until after the opening before departing for Venice, where he remained until late June.7

The following month he returned to the United States with more than twenty-five paintings, a group large enough for a solo exhibition. Only six paintings of non-Venetian subjects can be confidently dated to the nearly two years that remained of his life; therefore, it is safe to assume that he devoted this period to continued work on the Venice pictures, over half of which seem to have been unfinished when he died. The latter were signed by a hand and with inscriptions distinctly different from those on the works he completed: most of the autograph signatures contained his full name, followed by dashes separating the name from the location, “Venice,” and/or the date, “97.” That his mother and brother, who helped to organize the two memorial exhibitions, recognized these as his finished works is also apparent from photos of the National Arts Club memorial exhibition, in which five of them are visible.8 Several others bear the exhibition numbers from the St. Botolph Club exhibition, allowing us to match those paintings with the often-vague titles under which they were originally displayed.

At the time of the St. Botolph Club exhibition, all the Venetian paintings were listed as the property of Breck’s mother, Ellen F. Rice. According to a Breck descendant, Mrs. Rice herself signed almost all of the thirteen (now known) Venice paintings that were not exhibited and presumably not completed, and there are indications that another hand also applied finishing touches to those works.

Both memorial exhibitions included the same twelve paintings of Venice, representing about one quarter of the total number of paintings in those shows. Unlike nearly all of the other works included, these had never before been seen in public, and few of them have been seen by the public in the 120 years since.

Breck recognized the potential of Venice as an impressionist subject more than ten years before his mentor, Claude Monet, who did not visit the city until 1908. Although Breck was not the first painter to depict Venice using an impressionist technique, he was the first American to create a large body of Venetian views in that style (with the arguable exception of John Singer Sargent, who had not yet fully embraced the impressionist style). Several of his artist friends preceded him to Venice, notably Louis Ritter, John H. Twachtman, and Theodore Wendel, but aside from a small group Ritter had painted in 1889, their work had been done in the darker tones taught at the Munich Academy and by their then-mentor, Frank Duveneck (the subject of an article on pp. 82–89 of this issue). In around 1885 Ritter had actually painted a fresco of Venice in the Rutland, Massachusetts, home of Breck’s aunt and uncle, foreshadowing Breck’s later visit.

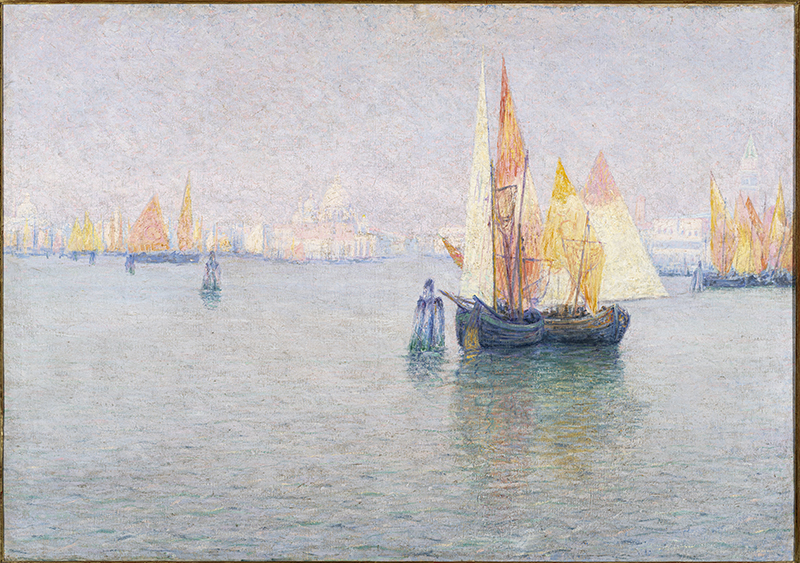

Despite years of abuse, the fresco has survived and bears a striking similarity to Breck’s Bay at Venice (Fig. 3), his largest Venice painting. Following the pattern he established in the four solo exhibitions he held during his lifetime, this would have been the first painting listed in his planned exhibition of Venetian works and the exhibition’s focus. Breck arranged the panoramic composition to include the entrances to Venice’s two major canals, the Giudecca and Grand Canals, and some of their principal buildings: Palladio’s Il Redentore church, the church of Santa Maria della Salute, and the Ducal Palace. The result is a comprehensive view that justified its title, simply Venice, in the earlier memorial exhibition.

Santa Maria della Salute is the sole subject of the next largest Venetian painting in the memorial exhibitions, Santa Maria by Moonlight (Fig. 1). Whereas he filtered his view of the bay through hazy sunlight, his painting of the Salute is a nocturne, a type of painting for which Breck had become famous early in his career.

Neither of these two paintings, the largest and most ambitious works included in the memorial exhibitions, is signed.9 Since Breck’s mother accompanied him on his trip to Venice, she must have understood their importance and realized as well that she should add neither a signature nor any finishing touches. The absence of a signature suggests that Breck did not yet consider them done, but there are no other indications that this is the case.

Little information about Breck’s activities during the last years of his life is known, and the only traces of his actual activities in Venice are the pictures themselves. Because so many of the works were painted either from or of the Giudecca island, Breck probably spent most if not all of his time living there. Giudecca is less frequented by tourists and home to much of Venice’s working class, and Breck focused in most of these paintings on the fishing boats and tackle with which the local inhabitants made a living (Figs. 4, 6).10

But he also chose subjects in the northern part of the lagoon: the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli on Murano; the cemetery island of San Michele and the small cluster of buildings at the heart of the remote island of Torcello, a subject rarely depicted by artists before or since (Fig. 8). Only the last of these was included in the memorial exhibitions. It is listed in both the inventories of Breck’s paintings compiled after his death, with the description “small, brilliant” in one.11 Breck’s mother retained ownership of the painting, which has remained with her descendants ever since. The subject allowed Breck to combine a wide range of colors, with a patch of green landscape not often found in Venice; the small canal leading into the town; and a cluster of stone buildings, dominated by the church of Santa Maria Assunta’s belltower.

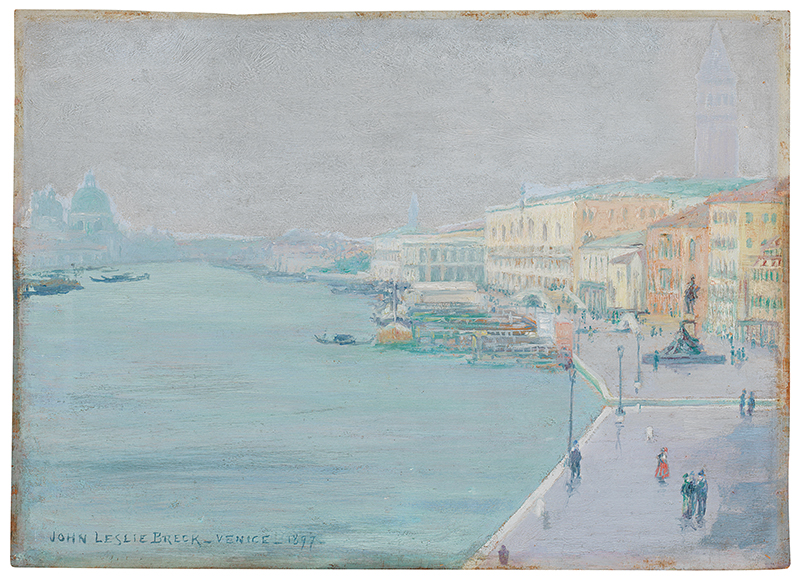

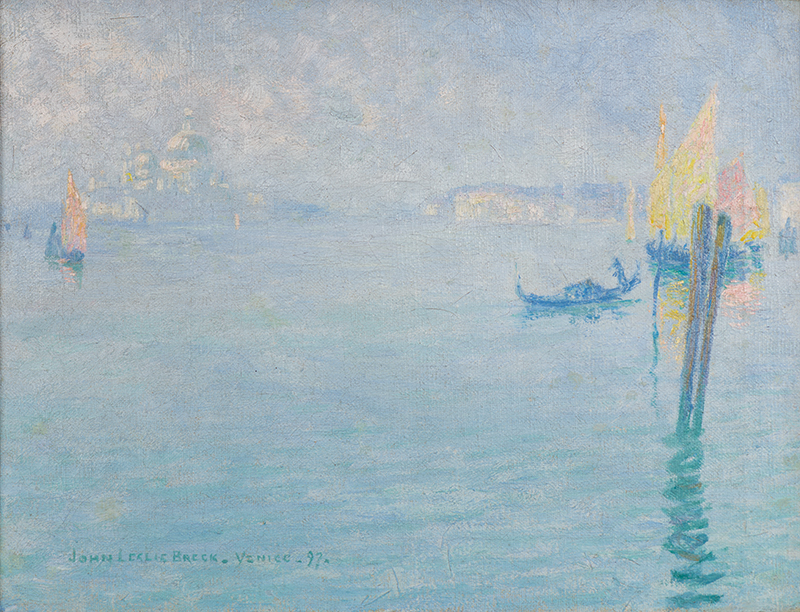

Venice posed a challenge to Breck. His earlier landscapes are distinguished by his lush use of the color green, and his seascapes evoked the deep blue of the North Atlantic. Venice contained few trees and gardens like those he had painted so often in the past, and when the Adriatic was not shrouded in mist, it sparkled with such strong reflected sunlight that its bay and many canals sometimes seemed almost white. His paintings of La Riva (Fig. 9) and San Giorgio (Fig. 10) are relatively literal, if beautifully rendered, portrayals of their subjects. But others veer into abstraction, anchored only by a piling or fishing boat in the foreground. In Santa Maria della Salute (Fig. 13), one of many views that Breck must have painted while floating on a gondola in the bay, water consumes the picture’s lower half, melting seamlessly into a mist-enshrouded sky, against which the church’s dome and spires faintly appear. Breck used a similar approach in San Giorgio Maggiore (Fig. 11). Misty Day at Venice (Fig. 12) is Breck’s most extreme experiment in decomposing form. Santa Maria della Salute is faintly visible from the light glinting off its dome, and he indicates the sails of several boats with high-keyed splashes of orange and yellow. Otherwise, mist veils the entire scene, blurring the horizon line.

Breck also completed nearly as many watercolors as oil paintings of Venice. Unlike the oils, however these were very small, the largest being just two by seven inches. They are his only located works on paper. With the exception of one watercolor, they were mounted as ensembles, a single pair and three sets of six, and many of them feature conventional portrayals of typical tourist sites, such as the Basilica of St. Mark, the Ducal Palace, the Rialto Bridge, and Santa Maria della Salute. While some of those monuments also appear in his oils, there they are usually foils or bystanders to atmospheric studies, whereas in the watercolors they are very much the main subject. Some pictures are almost identical. An exception is his eerie nocturnal view looking down the Grand Canal under moonlight (Fig. 7).

It is hard to grasp Breck’s motive for these works. None is exactly like any of the oils, so they do not seem to be studies, and they are too small to be independent works, which may explain why most of them were presented in ensembles. Because one group of six formerly belonged to Breck’s friend George W. Chadwick, he may have intended them as gifts. It is doubtful that he ever meant to exhibit them.

On the basis of exhibition records, photographs, inventories, and inscriptions on the paintings themselves, we can assume that almost all of Breck’s Venetian work has been located. This unusually complete body of work allows us to reconstruct the limited group of Venetian paintings that his memorial shows displayed to the public, teasing our imaginations with highlights of the larger exhibition that never was.

A major exhibition of John Leslie Breck’s work is scheduled to open at the Mint Museum in Charlotte, North Carolina, in September 2021 and to travel subsequently to the Dixon Gallery and Gardens in Memphis, Tennessee, and the Figge Art Museum in Davenport, Iowa. It will be the first large-scale exhibition of Breck’s work in more than 120 years.

1“Victim of Gas,” Boston Sunday Globe, March 19, 1899, p. 2. 2Postcard addressed to G. W. Chadwick, George W. Chadwick Papers, New England Conservatory Archives, Boston. 3“At the Hotels,” New York Times, November 14, 1896, p. 5. 4Heiner Gillmeister, “Edward Breck: Golf Champion, Master Spy and Attaché Manqué to the German Olympic Team,” n.p., n. 14, available at nga-earlygolf.nl. 5“At the Berlin Fecht-Club,” New York Herald [European edition], February 7, 1897, p. 6. 6“Pictures in Berlin,” New York Times, April 3, 1897, p. 13. 7“Society Doings in Berlin,” New York Herald [European edition], June 25, 1897, p. 4. 8Smithsonian Archives of American Art, National Arts Club Records, roll 4259, frames 1076–1078. 9They are Breck’s only Venice oil paintings that do not bear his name. 10Three paintings were exhibited as “Giudecca Canal,” one of which cannot be reliably identified and may be unlocated. The only other still unlocated Venice painting for which we have a record is one described in an inventory as “Venice Navy Yard, gray day, small.” 11Breck family papers, private collection.

ROYAL W. LEITH is an independent art historian and principal contributor to the catalogue, to be published by D. Giles, accompanying the forthcoming Breck show, for which he is also a consulting curator.