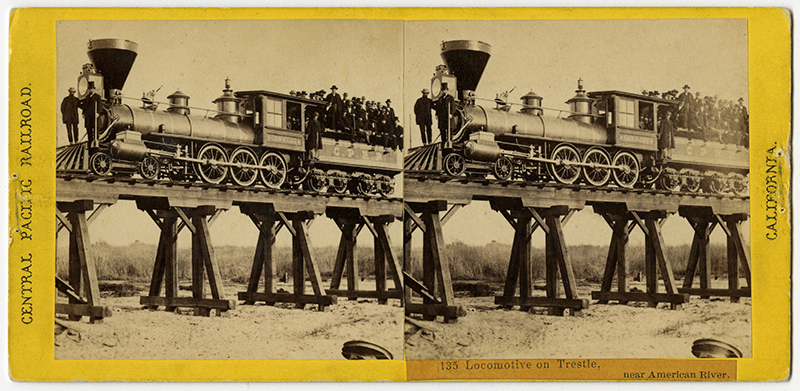

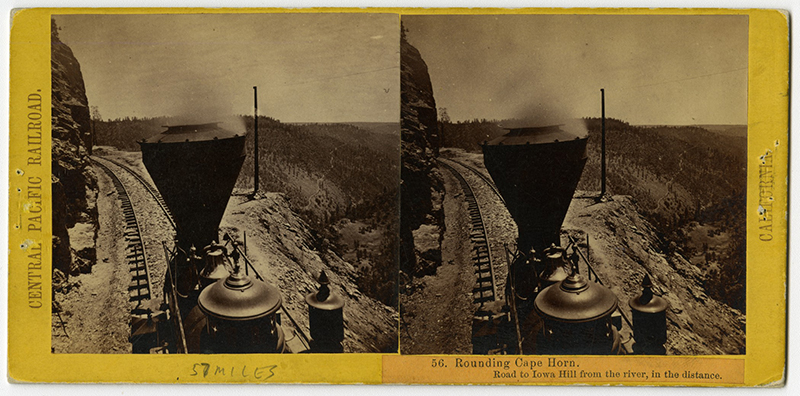

It was a vertiginous moment in the history of the young United States when the Central and the Union Pacific railroad companies linked up at Promontory Point, Utah, in 1869, marking the completion of the transcontinental railroad. The line’s boosters were intent on milking the moment for all it was worth, and on hand were two photographers, Joseph Russell and Alfred A. Hart, who’d been commissioned to follow the mostly Irish and Chinese work crews as they laid hundreds of miles of track across the mountains, forests, and deserts between the Mississippi River and Sacramento, California. Their pictures can be seen in Race to Promontory: The Transcontinental Railroad and the American West, a traveling exhibition organized by Union Pacific, which is making its final stop at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento this summer.

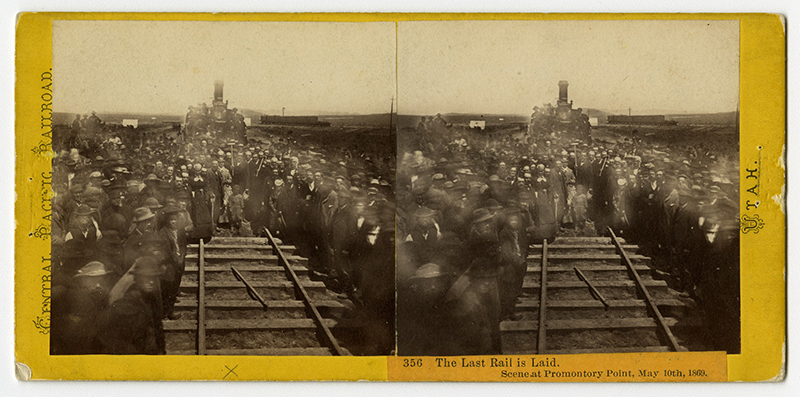

Both men shot that final, triumphant scene. What’s interesting is that, if Russell’s image of opposite locomotives mobbed by men in dusty work suits has been the more fêted of the two photos, it was perhaps Hart who can be said to have successfully captured the moment—spiritual dimensions and all—by using a long-outmoded photographic method: stereography.

A new technique in the still-new field of photography, stereography developed from stereoscopy, a method for studying scientific drawings in three dimensions pioneered by English inventor Charles Wheatstone. Its popularity skyrocketed after receiving the approval of Queen Victoria at London’s Great Exhibition in 1851, and by the middle of the decade stereoscopic (or binocular) cameras were being produced for the masses. Manufacturers of these devices—cameras mounted with a pair of lenses that made two parallel, simultaneous exposures—took their cue from human anatomy. By spacing the lenses two-and-a-half inches apart, the same distance that usually separates the pupils of a person’s eyes, it was possible to take a photo of the same subject from two slightly different angles. When the images were viewed simultaneously, as through a stereoscopic viewer, an illusion of depth was created, something known as stereopsis.

The technique was in full flower when the golden spike was being hammered home. Although enthusiasm for stereography would falter in the succeeding decades, gathering pace again in the early twentieth century (readers may remember the black Bakelite stereo slide viewers ubiquitous around mid-century) before finally dying away, the optical logic that undergirded it can be found everywhere today, from virtual-reality headsets, to self-driving cars, to 3D movie cameras.

Stereoscopic viewers are available at the Crocker to help visitors feel like they’re on the line in 1869. But here’s a little-known fact: all you actually need to make these pictures come to life are a pair of eyeballs. Stare at one of Hart’s double images and relax your eyes. Don’t strain. The right and left images should drift toward one another until, finally, they merge. A third, new, image appears. The railmen must have been pleased. What better way to advertise the consummation of Manifest Destiny, and the birth of something new?

The Race to Promontory: The Transcontinental Railroad and the American West is on view at the Crocker Art Museum in Sacramento, California, from June 23 to September 29.