Jerry Lauren’s extraordinary collecting journey.

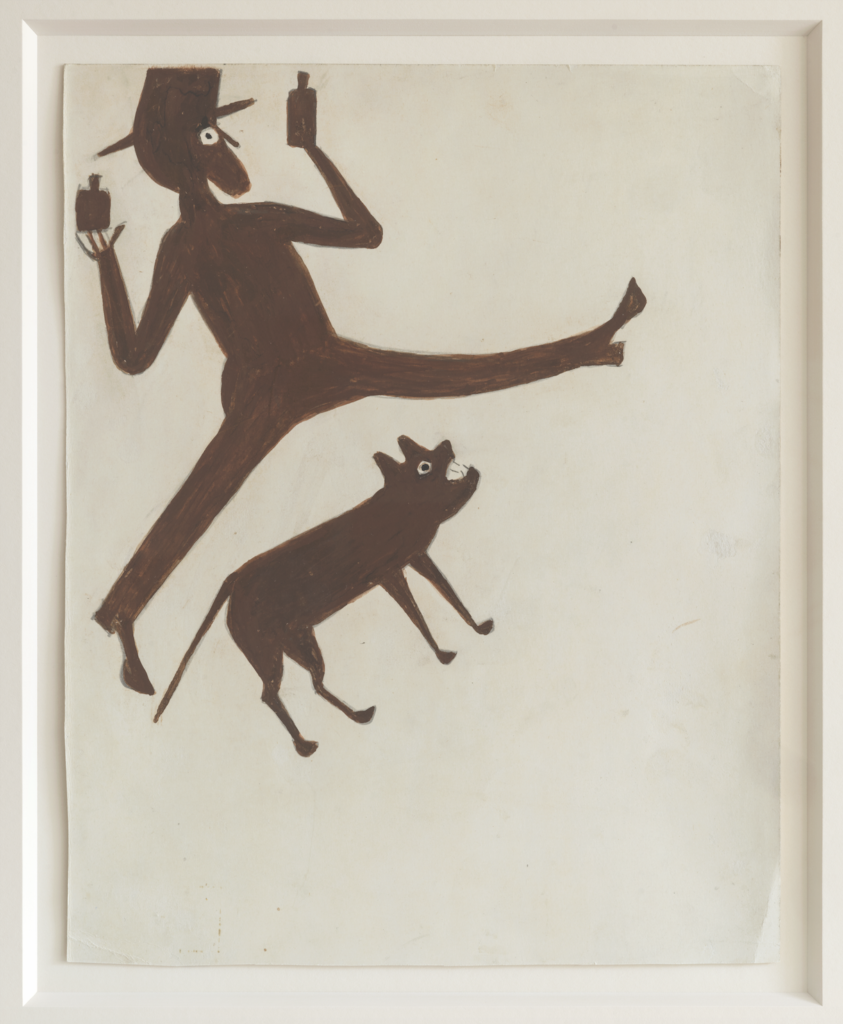

In November 2019, a powerful red tempera and graphite depiction of a man smoking next to a gesticulating woman had just arrived at Christie’s. The bold, bright piece with its ghostly abandoned underdrawing was a powerhouse work by artist Bill Traylor. I removed the frame’s backing to check for inscriptions, and saw an angry, red-tongued dog, mouth agape, positioned vertically with a gesturing man. Steven Spielberg had given this drawing to author Alice Walker after he filmed an adaptation of her novel The Color Purple, but neither knew the piece was double -sided.

I immediately thought of Jerry Lauren and, while still looking at the back of the painting, called him to come see the work. He was astounded. For him, art has always been a “love of perfection” in its many forms, and he found it in Man on White, Woman on Red / Man with Black Dog (double-sided). Jerry acquired the remarkable drawing in January 2020. “I had to have it home. It was snowing,” he recalls. “I said this to Christie’s deputy chairman and auctioneer John Hays. He ran through the snow, got a cab for us, and we carried it to my apartment. It was one of my great moments.”

During the lonely COVID isolation that followed, Jerry found solace in the beauty and stories of his art. In the bleak months of 2020, especially, we spoke on the phone about the joyful, comforting presence these objects hold in their aesthetic power and through the narratives that chronicle Jerry’s and his late wife, Susan’s, journey through the art world. “When we found the great ones, we knew it.” I ask how this journey began. “In the early 1980s we found a house in a bucolic small town in Litchfield County, Connecticut, vintage 1785, and it changed our lives. We needed to furnish and fill our new home. We found local country auctions and they became our entertainment and our discovery of American art.” Jerry and Susan met dealers Sy and Susan Rapaport, who became their trusted advisors and dear friends. “The Rapaports taught us how to look at this art and understand and recognize authenticity and quality as we searched for the best.”

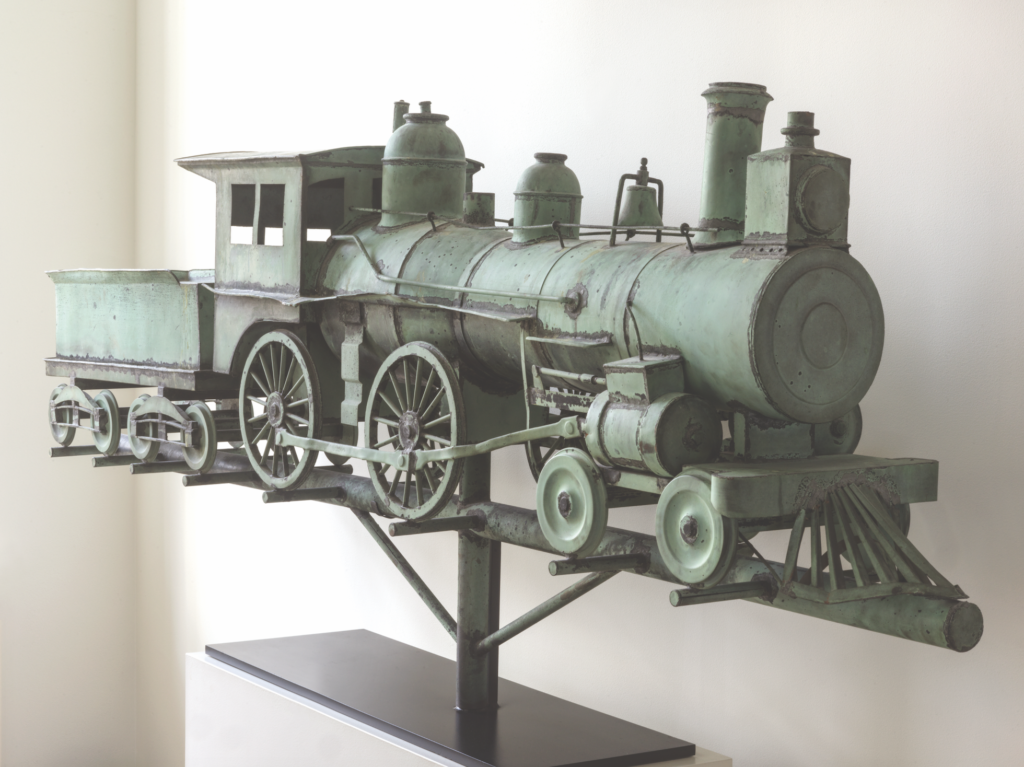

Jerry and Susan became formidable forces in the Americana collecting community with the acquisition of some of the most remarkable weathervanes. “They are truly masterpieces. The hunt was on, even to the extent that I was on the phone, bidding on an extraordinary weathervane, on the morning after my younger son Greg’s wedding. Sometime later, we were told about a six-foot locomotive that was going up at Skinner’s . . . every detail of the spokes on the wheels and the verdigris had perfectly aged.”

Indeed, the circa 1890 locomotive, which once stood atop a Massachusetts railroad building, with its elegant, finely crafted elements, proves the idea of weathervanes as ingenious sculpture. In some ways, it’s hard to imagine this impressive object atop a massive building when it feels so in place displayed on a pedestal in an apartment. But, its elegance in the space is no accident; rather it is a testament to the Laurens’ brilliant sense of design. When Susan first saw the weathervane, Jerry recalls, she said “I love it, but where would it fit?” His response: “Susan, do you love it? We’ll find a place.” The Laurens’ purchase of the record-breaking J. L. Mott “Indian chief ” weathervane at Sotheby’s in October 2006 solidified their reputation as major art-world players and brought new levels of attention to weathervanes and Americana.

From the Grosse Pointe, Michigan, home of Josephine and Walter Buhl Ford, the enormous vane remains unaltered, its surface perfectly imperfect through years of exposure and the aging process. Its shiny gold leaf has been replaced by variegated verdigris and exposed copper, nodding to its original state but speaking to its years of service and its reality. The scale is awesome, the detail of his feathered headdress, arrows, and clothing still crisp. The figure’s stance is majestic. “The auction was the ultimate challenge, and I got it. Winning that weathervane was an out-of-body experience.”

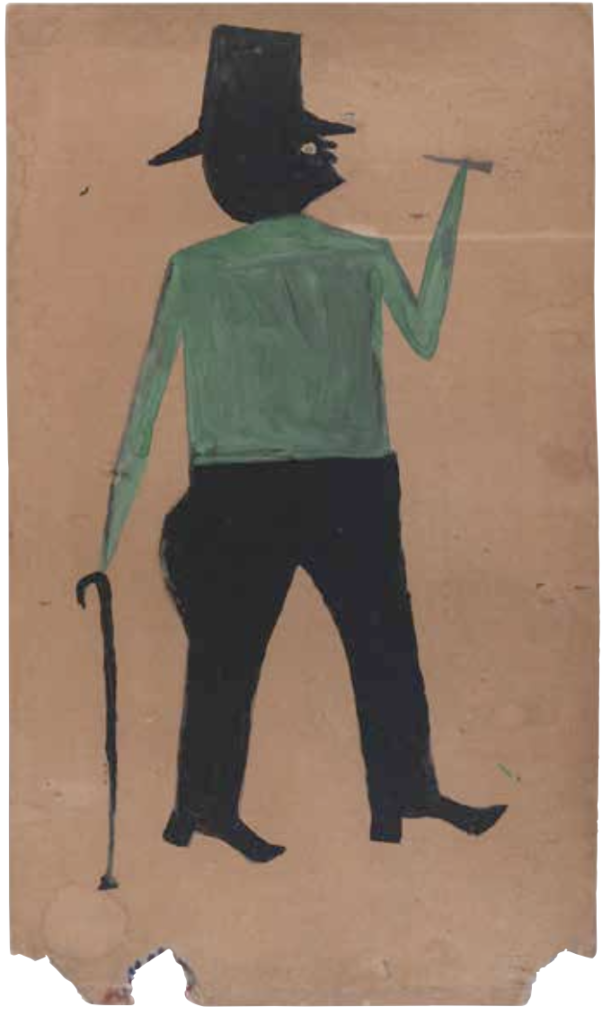

Jerry and Susan didn’t stop at the traditional boundaries of Americana. They sought great American works, period, and were especially drawn to those by Bill Traylor. “Sy Rapaport showed me a few Traylor images, then Susan and I went to Frank Maresca’s showroom. Frank had this painted figure in a green shirt with a cigarette and a cane. A very simple figure, but great. I called my daughter, Jenny, who is an artist, to come to the showroom. I said to her, ‘What do you think?’ She said ‘Dad, I love it.’ That was the beginning.”

“Bill Traylor was untrained, an ex-slave creating art on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama, as he was observing people and places and remembering his history. I love every Traylor that I own, and they are each different in their surprising elements.” Within Jerry’s seventeen Traylor drawings, the range is striking. Man on White, Woman on Red / Man with Black Dog shows the artist working through composition, form, and structure, and the finished piece is a perfect record of Traylor’s artistic process, complete with its abandoned underdrawings, switch in orientation of his page, and an exploration of the paper in its double-sided entirety. Another, 1939’s beautifully crisp tempera, Drinking Man with Dog, revels in direct and assertive brushstrokes, demonstrating a different artistic process.

And Jerry pushed things further. “I saw a [ Jean-Michel] Basquiat in an upcoming auction at Christie’s. It came from the collection of Andy Williams, which was very interesting because his collection was eclectic, including Americana. I was astounded by the Basquiat.” Featuring the barely harnessed energy and electricity of the greatest Basquiat works, the crisp and vibrant Furious Man has a frenetic and bold presence; the white hair on the figure seems a reference to the artist’s good friend Andy Warhol.

I asked Jerry how he decided, at that 2013 auction, to include this piece of “contemporary” art in his collection: “I thought it was true American folk art. It was about going for the best. I had scribbled my budget on an envelope as I sat in the sale room with Sy. I threw away the envelope and went for it. It was another miracle.”

Much has been written about Jerry and Susan’s collection, and their precision and patience are frequently highlighted. Their focus was never quantity, and they never felt rushed to fill in gaps, instead waiting patiently for incredible objects to emerge—seeking the “twelves” on a scale of one to ten. A further focus has been the connection between Jerry’s professional life as head of menswear for Ralph Lauren and his collecting aesthetic. The layered textures and understated elegance that appear in Ralph Lauren designs echo through his 1923 Park Avenue apartment. White couches, glass tables, and original herringbone floors add depth through texture and dimension that perfectly complement the art.

In previous articles, Lauren rightly extols the importance of his works’ original purposes. But what of their current function as a group? What do they tell us about the possibilities and expansions of American art? This selection of diverse American objects and artworks reevaluates the boundaries of traditional categorization and aesthetic

hierarchies. The Basquiat work on paper shares a wall with a vibrant, massive Bill Traylor and hangs adjacent to three exceptionally large stoneware face vessels. Weathervanes abound in the adjoining rooms, their verdigris and patina balancing the bright, fiery colors featured on the drawings. It works. It creates visual resonance. Whether the Laurens set out to push categorical boundaries, they certainly have done so.

These unexpected juxtapositions also push intriguing conversations between artworks, forcing a deeper reading of each object. Visual interactions between the furious Traylor dog and Basquiat’s Furious Man drive home the stylistic strengths of the artists. One can’t help but consider the physicality of each creator: a young Basquiat rapidly and energetically marking his page versus an elderly Traylor, working with a more considered, contemplative gesture. The freshness of Basquiat’s page, versus the repurposed, marked, scuffed paper of Traylor’s. The immediacy of fame versus the slow burn of a lifelong artistic incubation. In contrast to these works on paper, the remarkable weathervanes are beholden to the slow shifts in surface that develop over time, their power, richness, and depth reinforced by temporality. Surface is paramount, but the perfect surface can take many different forms.

In the eighth anniversary issue of Antiques and Fine Arts, Jerry said that for him to acquire a piece, “The object should be the perfect example of that particular form. . . . The object has to have its own life.” What happens when, governed by this approach, one builds a collection that spans from weathervanes and decoys to Basquiat and William Edmondson? According to Jerry, “It’s not a collection. It’s a happening. It was happening all along.” Just as the Laurens ignored boundaries of Americana, they were not constrained by the limits of a “collection”—a state of being in or out.

This “happening,” then, succeeds and successfully pushes boundaries because of its precision and focus. There are no extraneous works. William Edmondson’s subtle, elegant Fox was acquired two years ago at Christie’s and now has pride of place in the living room, seemingly floating above a sofa in front of a large, unique, wooden

rooster weathervane of about 1785.

Fox flourishes because it engages the other Edmondsons in the room, each of which presents the artist’s work

through a different lens: of strength and power (Lion), of intimacy and delicacy (Mother and Child), and of devotion and faith (Ram). Ultimately, the pursuit of quality, authenticity, strength, and discovery are the common threads throughout the Laurens’ carefully selected, wide-ranging works.

“There’s never a day that I don’t love what Susan and I discovered. It is pretty amazing.”