Most of New York City’s Victorian heritage has vanished so thoroughly that few of the locals have any idea that it ever existed. How many of the residents realize that, before the present Grand Central Terminal opened in 1913, an entirely different Grand Central—virtually identical in footprint and function, but thoroughly Victorian in design—occupied the very same site for almost half a century? Other than a few row houses and the occasional civic building, almost nothing survives in New York from before 1880.

But there is one great exception to these meager remains—so great, in fact, that it is apt to be entirely overlooked: Central Park, which was conceived in 1858 and opened in 1867. As such, it may properly be seen as the largest single antique in the city of New York. Although it is contemporary with the Civil War and with Haussmann’s work in Paris, it is also the city’s pre-eminent theater of life itself, both in the energetic exercise that Gothamites enjoy within its 843 square acres and in the annual rebirth of its magnificent trees and flowers and lawns. That clamorous vitality, surely, is what obscures the fact that it is one of the oldest artifacts in a city not known for respecting its past. But its Victorian heritage is evident at almost every turn, a fact brought vividly to life in a most welcome new book, The Central Park: Original Designs for New York’s Greatest Treasure. Nearly two hundred exquisite watercolors, either executed or commissioned by the park’s creators, Frederick Law Olmsted, Calvert Vaux, and Jacob Wrey Mould, have been expertly compiled and intelligently explained by Cynthia S. Brenwall of the New York City Municipal Archives. To these have been added numerous old photographs from the same source, illuminating the park’s history in the century and a half since its completion.

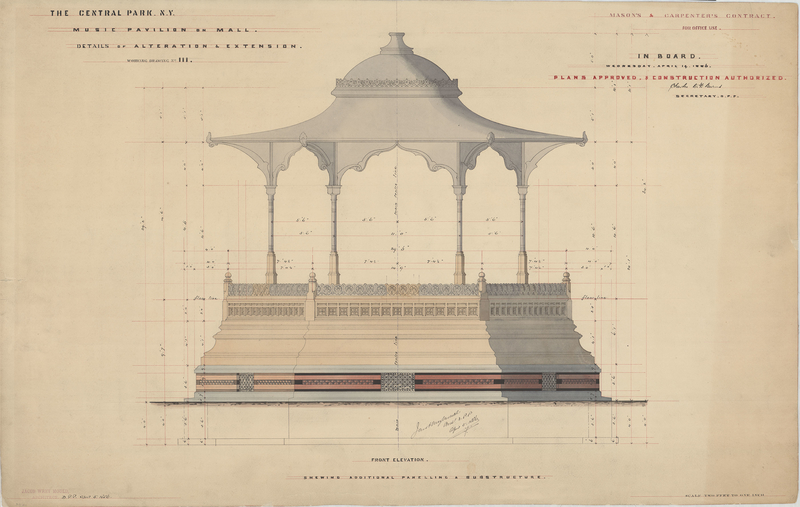

The reader will notice that the book is titled The Central Park, since the definite article was indeed attached to its name before the locals, in the unconscious evolution of their usage, decided otherwise. Many other aspects of the park have changed over the past 150 years, through the removal of some original elements and through the addition of others that its creators either vigorously opposed or could never even have imagined. The Persian birdcages and the Moorish bandstand in the Mall are all gone, together with the sheep that once grazed in the Sheep Meadow. At the same time, four grand entrances, one at each corner of the park and ultimately inspired by the City Beautiful movement of 1900, have encroached upon the rustic simplicity that the founders envisaged. And although Mayor de Blasio has done the citizens a great favor by removing cars from the park, the gray, macadamized thoroughfares remain, and buildings taller than the citizens of the nineteenth century could have conceived in a fever dream now form an ever-present and inescapable fringe around the park.

Like every built structure, a park embodies an idea of living and of leisure, and the idea that animated the creators of Central Park corresponds only partially to the way we live now. Through massive intervention in the pre-existing landscape (and by removing small communities such as Seneca Village, a largely African-American settlement located in the West 80s) the park’s designers sought to create a precinct of bucolic peace cut off from the raucous city that surrounds it. Nevertheless, they allowed for one main avenue of formal design, stretching along the Mall from Sixty-Sixth Street to Bethesda Terrace beside the lake. The entire stagecraft of Central Park was conceived around this essential corridor, the grand coup de théâtre of the entire project. But the original purpose of the Mall was to serve as a stylish promenade where the well-to-do could preen before their peers, an ambition entirely alien to how we use the park today. In a word, the original park was intended as a salubrious stage set to be passively admired as pedestrians strolled through it. Their main physical interaction consisted of sitting on a bench or, in the heat of summer, reposing in one of its dark, submerged tunnels. There was not even a formal playground in the park until 1927. Today, however, as refashioned by Robert Moses in the 1930s, the park is a zone of intense physical engagement, while its acres of magnificent lawns, once an undisturbed green backdrop, are covered in sunbathers, picnickers, and Ultimate Frisbee players.

But in spite of these many differences, and largely through the good works of the Central Park Conservancy, founded in 1980, the essence of the park remains very much as its designers intended. If they could return today, they would immediately recognize the landscapes that they had created out of nothing and with a skill that concealed all trace of their art. So thoroughly did they reconstitute the rocky, unlovely terrain of this part of Manhattan—largely useless for real estate development—that what we see today, although formed from the living tissue of pre-existing flora and marshes and stone outcroppings, is as much a nineteenth-century artifact as the Nouveau Louvre of Napoleon III or the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. Its guiding spirit was that of English garden design: the picturesque asymmetries of ever-changing landscapes succeed one another so well that the park as a whole is experienced as being far larger than it really is. The very names of these varied landscapes are intensely English, strongly suggesting the Episcopalian mood in which the park was created: the Dene, the Glade, Pilgrim Hill, and so forth. Despite its abundant statuary, no new statue has been added in over half a century, and most, dating to the latter half of the nineteenth century, reflect the values and dominant ethnicities of that earlier age: Schiller, Beethoven, and Alexander von Humboldt; Christopher Columbus and Giuseppe Mazzini; Shakespeare, Robert Burns, and Sir Walter Scott.

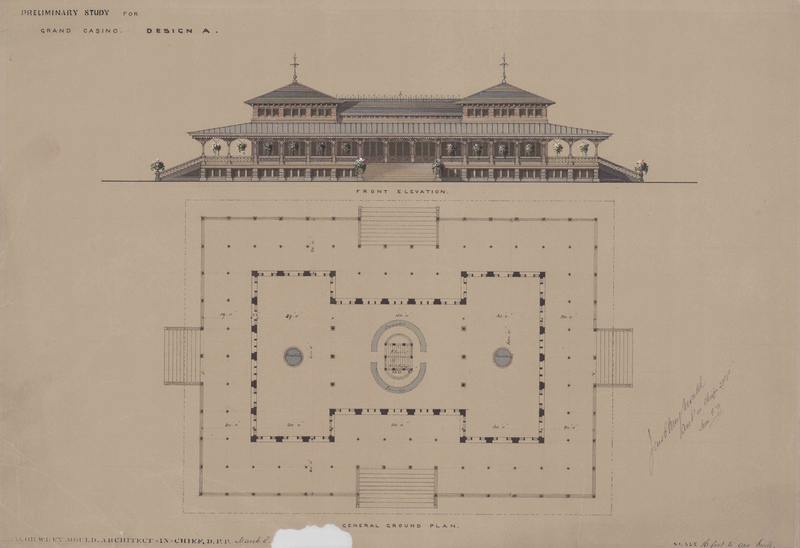

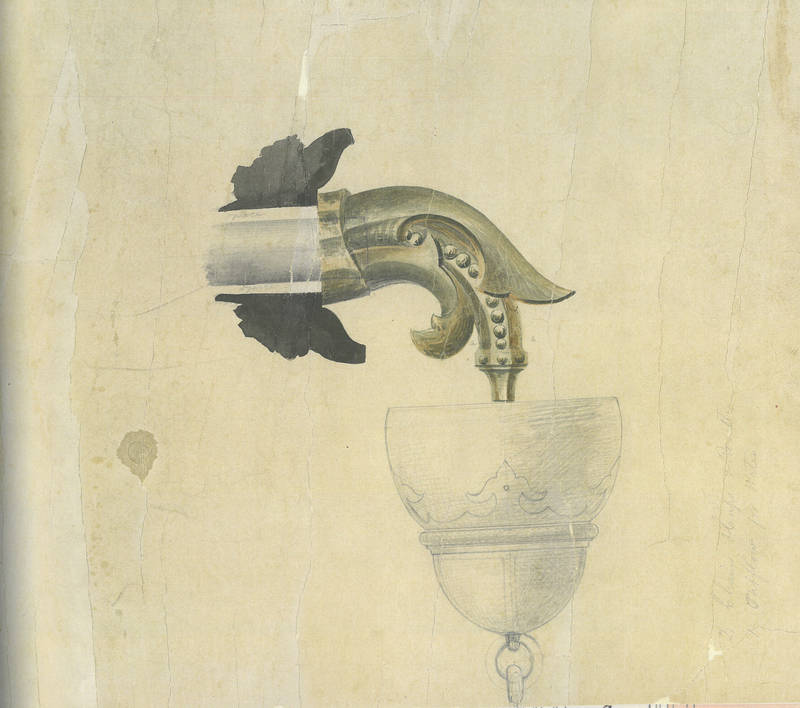

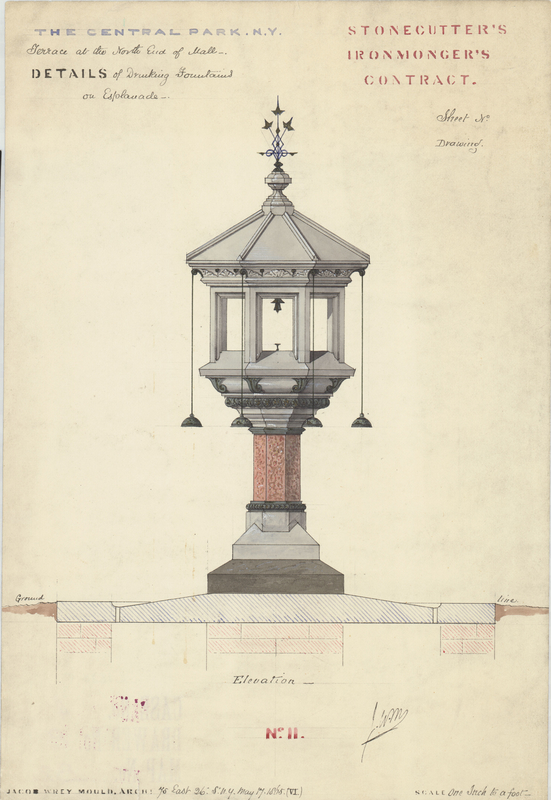

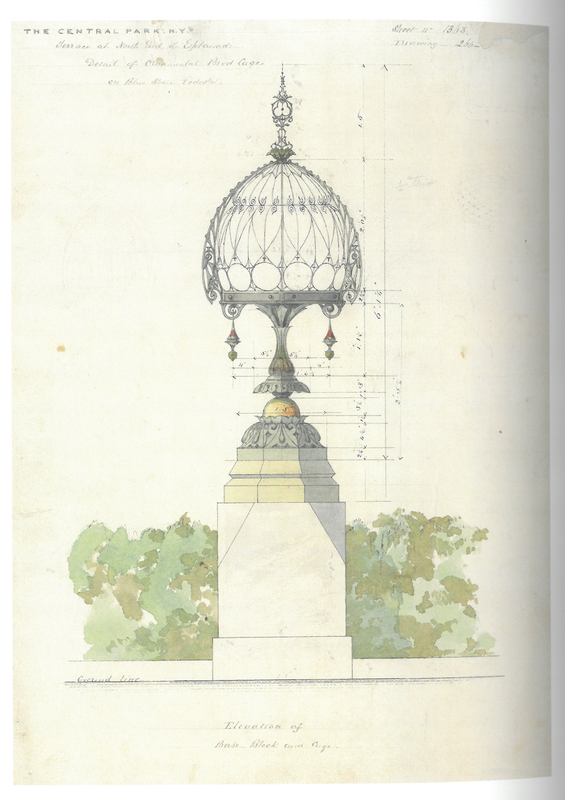

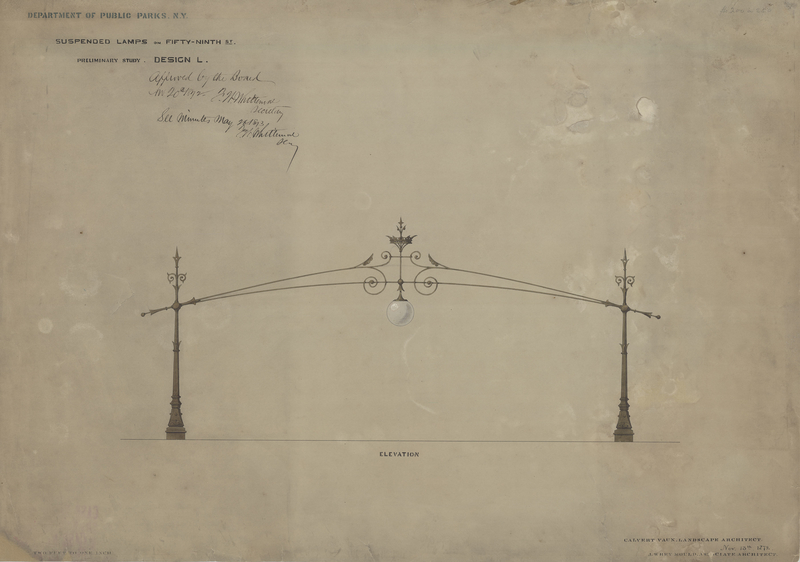

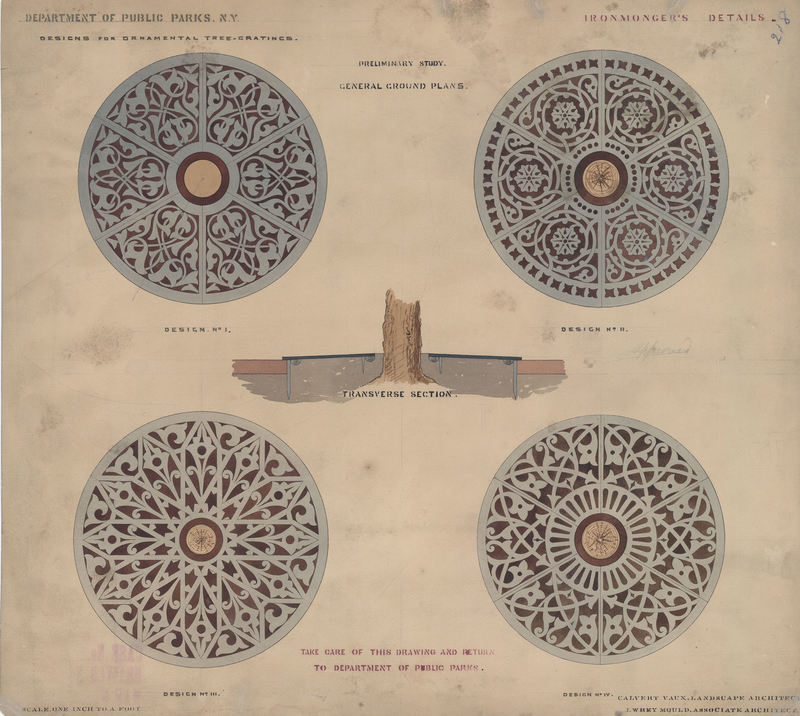

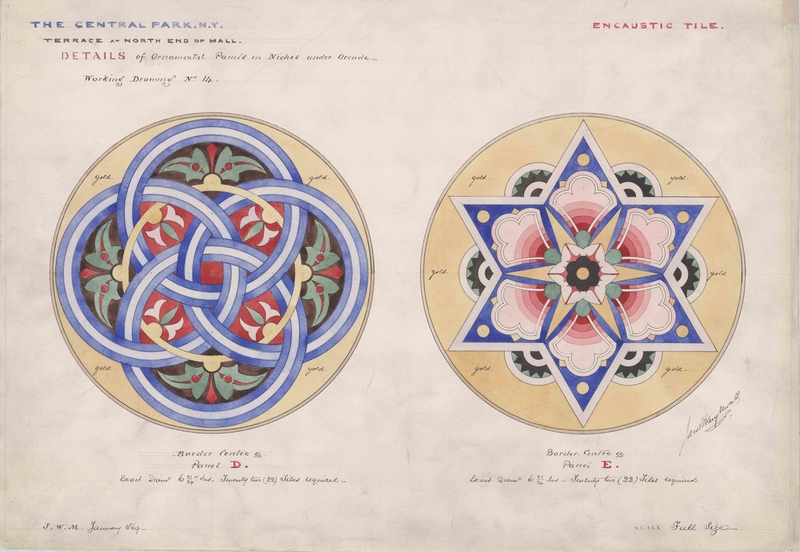

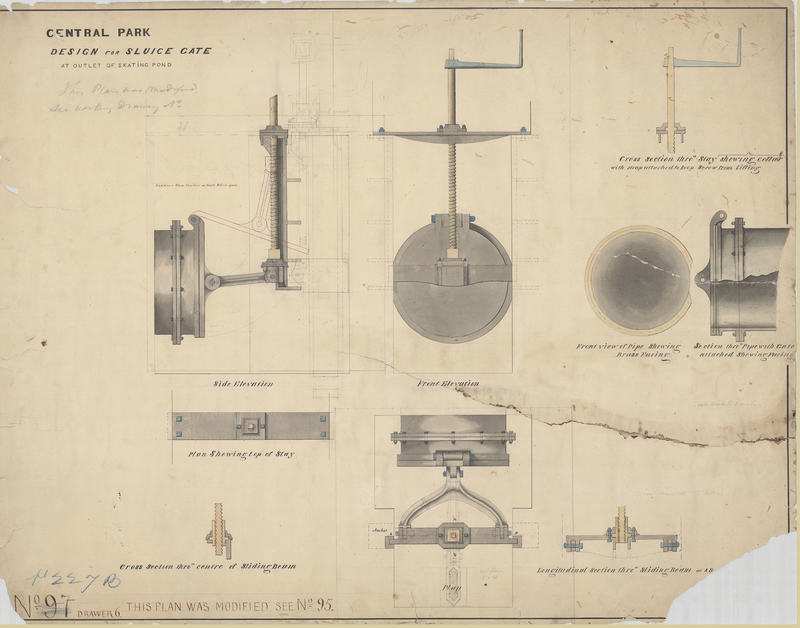

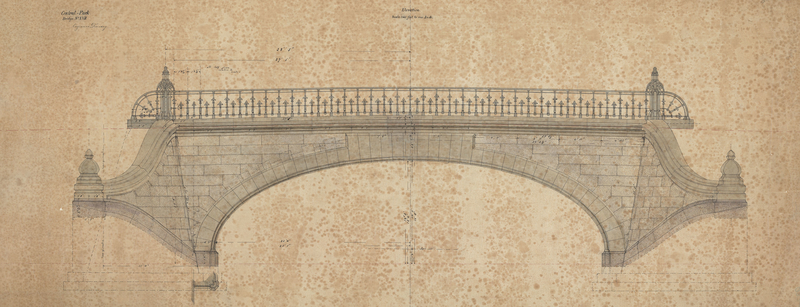

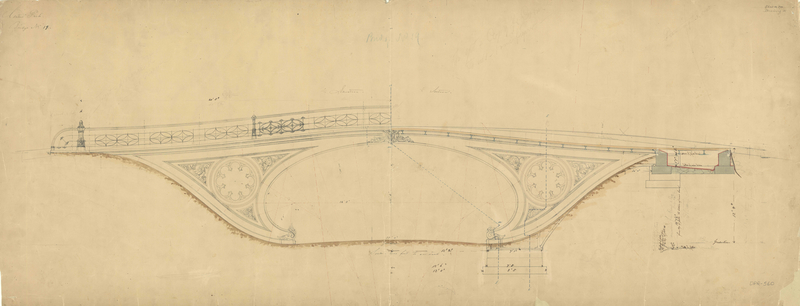

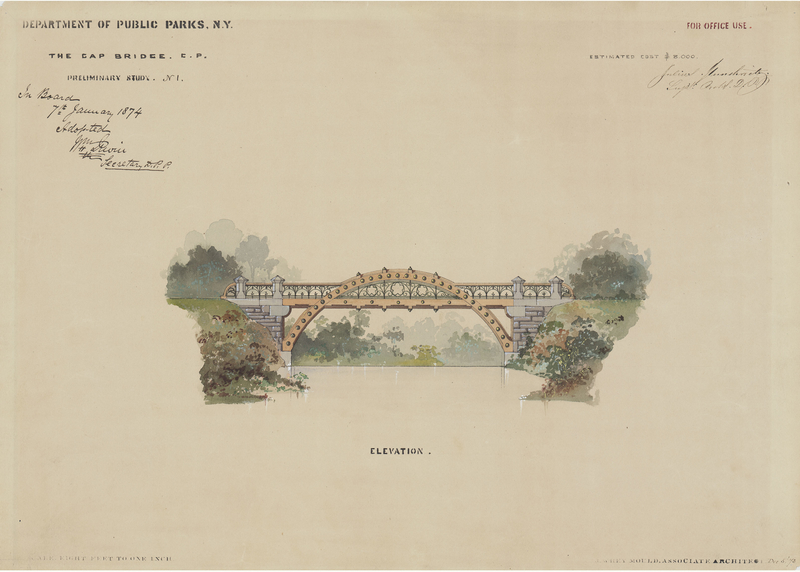

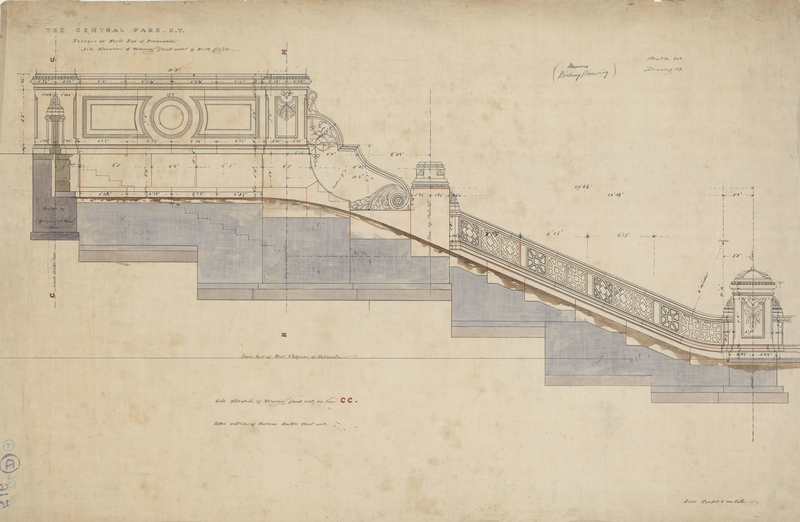

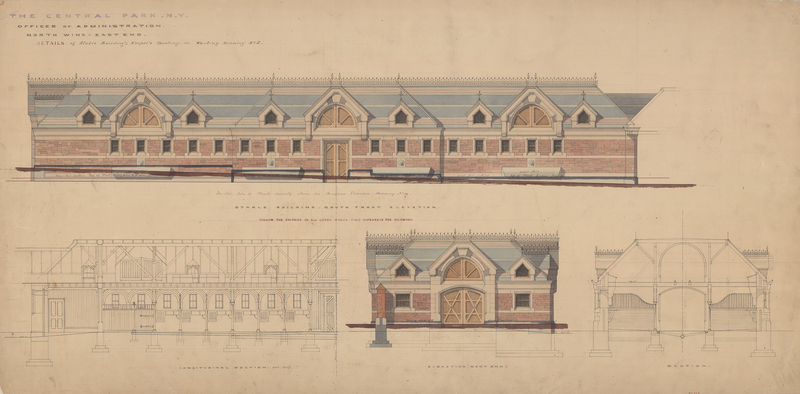

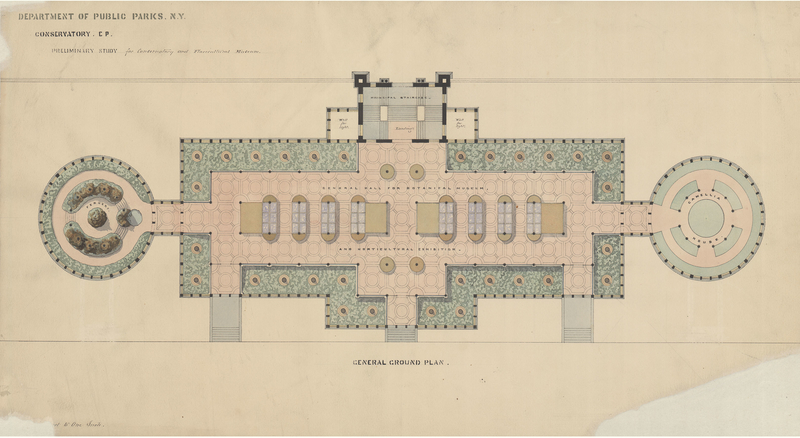

But the most striking remains of the original park are the many architectural interventions that are the subject of the watercolors chosen by Cynthia Brenwall. The middle years of the nineteenth century were, of course, the high-water mark of architectural historicism, the guiding principle of which was that the here-and-now must be rejected in favor of the there-and-then. Each of the thirty-three bridges and tunnels of Central Park, among them the Grayshot Arch and the Dipway Arch, the Willowdell Arch and the Trefoil Arch, whether conceived in cast iron or in stone, was designed to transport the visitor to some far-off world and some more halcyon age. And the main vector of that time travel was a superabundance of Victorian ornament, which concealed the often-modern means of construction. If the Romanesque revival arches of Belvedere Castle carried us back to the Middle Ages and if the fussy finials and Minton tiles of Bethesda Terrace landed us in Renaissance France by way of South Kensington, the Dairy and the Sheepfold that are now the site of Tavern on the Green took us to the rural England of Shakespeare’s day. The doyen of such historicist ornamentation was Owen Jones, the Victorian antiquary who played an important role in creating London’s Crystal Palace. His Grammar of Ornament was one of the breviaries of the age, and it was the basis for the work that Jacob Wrey Mould, who had studied with Jones, carried out in Central Park.

Most of his designs survive to this day, integrating themselves into and enriching the lives of the millions of locals and tourists who visit the park each year. And thanks, once again, to the Central Park Conservancy, Central Park is now in better condition than it has been in over a century. Indeed, it looks every bit as fresh and sparkling and new as in the drawings included in Brenwall’s invaluable new book.